Published online Oct 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670

Peer-review started: March 24, 2016

First decision: May 16, 2016

Revised: June 18, 2016

Accepted: July 29, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: October 18, 2016

Processing time: 202 Days and 16.4 Hours

To assess the functional and clinical results of repair of chronic tears of pectoralis major using corkscrew and sliding suture technique.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the results of pectoralis major repair in 11 chronic cases (> 6 wk) done between September 2011 and December 2014 at our institute. In all cases repair was done by same surgeon using corkscrew suture anchors and box suture sliding technique. At 6 mo, after surgery magnetic resonance imaging was done to see the integrity of the repair. Functional evaluation was done using Penn and ASES scores. Pre and postoperative Isokinetic strength was measured.

Average follow-up was 48.27 ± 21.0 mo. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the outcome scores. The average ASES score increased from an average of 54.63 ± 13.0 preoperatively to 95.09 ± 2.60 after surgery at their last follow-up. The average Penn score also increased from 5.72 ± 0.78, 2.81 ± 1.32 and 45.81 ± 1.72 to 9.36 ± 0.80, 8.27 ± 0.90 and 59 ± 1.34 for pain, satisfaction and function respectively. Follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (at 6 mo) showed continuity and the bulk of pectoralis major muscle in all cases. Average isokinetic strength deficiency in horizontal adduction at 60° was 13.63% ± 6.93% and at 120° was 10.18% ± 4.93% and in flexion at 60° was 10.72% ± 5.08% and at 120° was 6.63% + 3.74%. Results showed that both ASES and Penn score improved significantly (2 tailed P value = 0.0036).

We could conclude from this series that pectoralis major repair even in chronic cases using 5.5 mm corkscrew anchors give excellent functional and cosmetic results. In chronic cases the repairable length of the tendon is not available and sliding suture technique allows for fixation of worn out tendomuscular junction to bone without letting cutting through the muscle.

Core tip: We are presenting the results of repair of rare chronic tears of pectoralis major. This is one of the longest series of repair of chronic pectoralis major tears by corkscrew suture anchors with midterm follow-up. In chronic tears hardly any repairable length of the tendon is available and what available is largely musculotendinous unit. We used a new technique to prevent cutting through of sutures from retracted musculotendinous unit in chronic tears. We have obtained excellent results with this technique.

- Citation: Joshi D, Jain JK, Chaudhary D, Singh U, Jain V, Lal A. Outcome of repair of chronic tear of the pectoralis major using corkscrew suture anchors by box suture sliding technique. World J Orthop 2016; 7(10): 670-677

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i10/670.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i10.670

Pectoralis major tear is a relatively rare and extremely traumatic orthopedic injury. Recently there has been an increase in reporting of such cases, especially in young, athletic males between 20 to 40 years of age, who are into body building or weightlifting sports[1]. Pectoralis major muscle has 2 heads of origin, sternocostal and clavicular. Sternocostal part forms the deeper posterior lamina and inserts more proximally on humerus and clavicular part forms the anterior lamina and inserts distally. Sternocostal part primarily internally rotates and adducts the shoulder whereas clavicular part forward flexes and adducts the shoulder. Traditionally, pectoralis major tear were being managed conservatively, but recently the surgical management of pectoralis major repair especially in young athletes has been recommended[2]. Cases of repair of both acute and chronic tear of pectoralis major have been reported. Tietjen[3] classified these injuries into three classes: (1) sprain; (2) partial tear; and (3) complete tear. Complete tear is further classified into tear of (1) muscle origin; (2) muscle belly; (3) musculotendinous junction and of tendon itself (4) recently, two more subclasses have been added[4-8]; (5) bony flake avulsion of the tendon; and (6) intratendinous ruptures. Chronic tears of pectoralis major are different from acute tears as the repairable length of the tendon is hardly available for fixation. This makes fixation difficult as cutting through the retracted musculo-tendinous junction of sutures is likely. This led us to develop a new technique which resulted in excellent results in chronic cases of this rare injury.

In this article we are reporting our experience of repair of chronic tendon rupture of pectoralis major muscles in 11 cases where we assessed clinical, functional and cosmetic results and incidence of re-rupture.

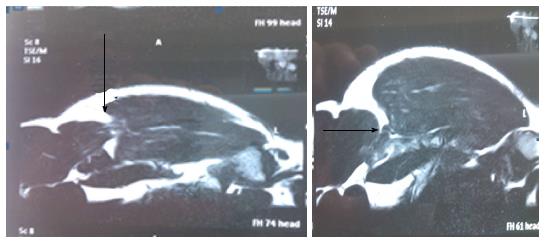

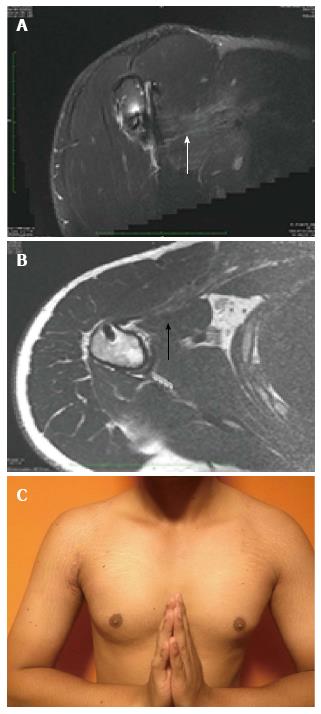

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the results of the pectoralis major repair in 11 cases (Table 1) done between September 2011 and December 2014 at our institute. The inclusion criteria were all chronic cases (> 6 wk) of pectoralis major tear repair who had minimum 2-year follow up with the availability of all medical records. All patients presented with common complaints of weakness of involved shoulder and loss of shape/bulge of axillary border. All cases felt sudden tearing sensation and pain in the axilla at time of injury. This was followed by development of bruises and swelling in the axilla. All were managed conservatively for at least 6 wk by local practitioner before presentation (range 1.5-4 mo). On examination, there was a weakness of adduction and internal rotation strength on the involved side compared to the other side and there was a loss of the anterior axillary fold (Figure 1). No patient gave a history of the use of anabolic steroids or any local injections. Diagnosis was confirmed by radiologist in all cases on MRI scan. Multi-planar coronal oblique and axial scans (T2-weighted fat-suppressed and proton density-weighted fat-suppressed images) were taken in all cases. Interstitial edema, retracted tendons and tear with fluid signal were considered positive findings to make the diagnosis. All patients were managed surgically.

| S/NProfession | Age/sex | Mode of injury | Type of tear | Time between injury and surgery | Follow up | ROM | Penn Score pre surgery | Penn Score (at final follow up) | ASES | Cosmetic appearance | |

| Pre-surgery | Post- surgery | ||||||||||

| 1 Student | 24/M | Bench press, 190 kg | Both heads avulsion at bony insertion on the humerus | 4 mo | 82 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction- 3 Function-45 | Pain-10 Satisfaction-9 Function- 60 | 40 | 98.33 | No complaints |

| 2 Wrestler | 25/M | Bench press, 180 kg | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 3 mo | 80 mo | Full | Pain-5 Satisfaction- 4 Function-46 | Pain-10 Satisfaction- 9 Function- 60 | 43.33 | 98.33 | No complaints |

| 3 Gym trainer | 27/M | Bench press | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 3 mo | 68 mo | Full | Pain-7 Satisfaction- 3 Function-44 | Pain-9 Satisfaction-9 Function-58 | 45 | 91.66 | No complaints |

| 4 Kabaddi player | 25/M | While playing Kabaddi (Forceful abduction and extension) | Both heads avulsion at bony insertion on the humerus | 1.5 mo | 56 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction- 3 Function-45 | Pain-8 Satisfaction-7 Function-58 | 42.77 | 96.1 | No complaints |

| 5 Wrestler | 30/ M | Bench press, 150 kg | Both heads avulsion at bony insertion on the humerus | 3 mo | 50 mo | Full | Pain-5 Satisfaction- 3 Function-45 | Pain-8 Satisfaction-7 Function-56 | 40 | 91.66 | Not fully satisfied with cosmetic appearance |

| (Changed profession due to pain in carrying weight) | |||||||||||

| 6 Wrestler | 27/M | Bench press | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 2 mo | 44 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction- 3 Function-45 | Pain-9 Satisfaction- 8 Function-60 | 68.32 | 93.33 | No complaints |

| 7 Weightlifter | 25/M | Bench press, 170 kg | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 3 mo | 40 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction- 3 Function-45 | Pain-9 Satisfaction-7 Function-60 | 78.32 | 98.33 | Not fully satisfied with cosmetic appearance |

| 8 Wrestler | 28/M | While wrestling | Both heads avulsion at bony insertion on the humerus | 2 mo | 32 mo | Full | Pain-4 Satisfaction-0 Function-44 | Pain-10 Satisfaction-8 Function-58 | 61.66 | 95 | No complaints |

| 9 Weightlifter | 20/M | Bench press 165 kg | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 1.5 mo | 30 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction-3 Function-48 | Pain-10 Satisfaction-9 Function-59 | 63.31 | 93.33 | No complaints |

| 10 Student | 27/M | Bench press | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 3.5 mo | 25 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction-5 Function-48 | Pain-10 Satisfaction-9 Function-60 | 61.64 | 98.33 | No complaints |

| 11 Weightlifter | 23/M | Bench press 160 kg | Sternal head avulsion at bony insertion on humerus | 2 mo | 24 mo | Full | Pain-6 Satisfaction-1 Function-49 | Pain-10 Satisfaction-9 Function-60 | 56.66 | 96.66 | No complaints |

Patients were followed up at 2, 6, 12 and 24 wk and subsequently at 3 monthly intervals and assessed clinically by range of motion and strength measurement. After surgery, shoulder was immobilized in a sling for 3 wk. Passive forward flexion and abduction were started after 2 wk. External rotation was restricted to 15 degrees in 1st 6 wk. Range of motion was gradually increased to achieve full range of motion by 3 mo. Strengthening exercises were started by the end of 2 mo and gradually increased from isometric exercises to isotonic exercises. Postoperatively results were assessed by American shoulder and elbow assessment (ASES) score, Penn scores and bilateral isokinetic strength testing by Humac™ (CSMI, Stoughton, MA). Deficit in strength was calculated as the percent difference between the higher and lower peak torque of the two limbs divided by the highest peak torque at 60 degrees and 120 degrees. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess the difference in pre and post-operative ASES and Penn scores and isometric strength.

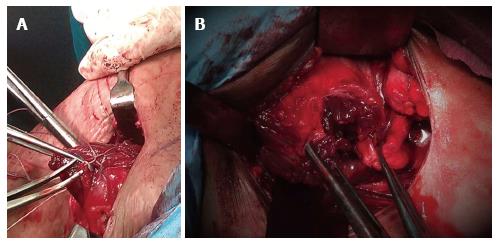

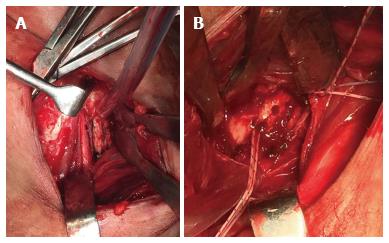

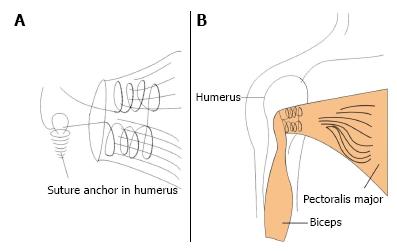

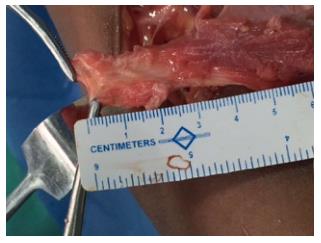

Patients were operated in the beach chair position. An incision of 5 cm was given in distal part of deltopectoral groove. Torn tendon of pectoralis major was identified and mobilized (Figures 2 and 3). The lateral lip of bicipital groove was exposed and its base was roughened with a rasp and drilling. Two double loaded 5.5 mm corkscrew anchors (Arthrex, Naples, United States) were deployed into the lateral lip proximally and distally at the insertion site of the tendon (Figure 4). Pectoralis major tendon was then attached to the lateral lip of bicipital groove with the help of anchors. The suturing was done in a box like fashion in the musculotendinous area to have a broader fixation and sliding knots followed by the half hitches were applied with post being the free thread (not through the muscle tendon).This brings the broad bulk of muscular tissue in approximation to the insertion site. The technique (box suture-sliding technique, Figure 5) holds good for these types of chronic cases where the torn tendon often gets attrition and it is difficult to achieve secure fixation in the worn out tendon.

All patients were young and active (mean age 25.54 ± 2.60 years). Mean follow up was 48.27 ± 21.0 mo. Mean time from injury to surgery was 2.59 ± 0.83 mo. Nine cases sustained injury while doing bench press exercise in the gymnasium, one patient sustained injury while playing Kabaddi (A popular contact sport in South Asia) and one patient while wrestling. MRI showed near complete tear of the pectoralis major at axillary fold level in four cases and tear of Sternal head in seven cases (Figure 2).

All patients achieved their pre injury exercise level in gymnasium between 9 and 12 mo postoperatively and returned to their previous occupation except one patient (wrestler) who changed the profession due to pain in overhead activity and difficulty in carrying weight. All patients were happy with the cosmetic result regarding the appearance of axillary fold, compared to the other side (Figure 6C) except two patients. At 6 mo, all cases were able to do bench press with minimum 70 kg weight. There was no complication till last follow up. No patient suffered re-tear of the repair till last follow-up.

The average ASES score increased from an average of 54.63 ± 13.0 preoperatively to 95.09 ± 2.60 after surgery at their last follow-up. The average Penn score also increased from 5.72 ± 0.78, 2.81 ± 1.32 and 45.81 ± 1.72 to 9.36 ± 0.80, 8.27 ± 0.90 and 59 ± 1.34 for pain, satisfaction and function respectively. Follow up MRI (at 6 mo) showed continuity and the bulk of pectoralis major muscle in all cases (Figure 6A and B). Average isokinetic strength deficiency in horizontal adduction at 60° was 13.63% ± 6.93% and at 120° was 10.18% ± 4.93% and in flexion at 60° was 10.72% ± 5.08% and at 120° was 6.63% ± 3.74%.

Statistical analysis: The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess the difference in pre and post-operative ASES and Penn scores and isometric strength. Improvement in ASES score and all components of Penn scores were significant (Two tailed P = 0.0036, P < 0.05).

Athletes usually sustain pectoralis major injury as a result of violent, eccentric contraction of the muscle during athletic activities. Sudden forceful abduction and external rotation of contracted muscle is the usual mode of injury. Bench-pressing weights has been reported as the most common mode of injury[4,8]. Other common modes of injury include rugby, football, wrestling and water skiing[5-7]. Type IIID (tendon tear) tear is the most common with a rate of 65%, followed by the type IIIC tears[8]. To date just over 60 articles and 350 cases have been reported in English literature[9]. Although first case was reported in 1822 more than 75% cases have been reported in last 20 years[9]. This simply reflects the advancement of diagnostic modalities and our understanding of these injuries. Use of anabolic steroids has been reported as a risk factor in weightlifters in such cases[10]. Sternocostal part stretches when the arm is abducted, externally rotated and extended and it fails more often before the clavicular part[11].

Wolf et al[11] in a cadaveric study showed that lower fibers of the sternocostal part are disproportionately lengthened and stressed in the last 30 degrees of extension. This explains why sternocostal part ruptures more often and before clavicular part. Females are less commonly exposed to high velocity sports and high end muscle building exercises. In addition to this larger tendon to muscle diameter in women has also been suggested[12] for almost no incidence of pectoralis major tear in females.

Since the reporting of the 1st case of pectoralis major muscle tear by Patissier[13] in 1822 its treatment has evolved from conservative to surgical management. Now most of the tears are treated surgically except for tears in elderly patients, those with sedentary lifestyles and minor muscle belly rupture[7,14]. While conservative treatment has shown poor results[15,16] surgical treatment has produced excellent outcomes[7,8,13,15] and is the preferred treatment now. In a large series of surgical repair of pectoralis major tear, Aärimaa et al[12] showed that early surgical repair has better outcomes than delayed repair. Eight weeks have been reported as an ideal time for surgery of pectoralis major tear[15]. Patients who are treated conservatively show good relief in pain and achieve range of motion compared to surgically treat patients, but they fail to achieve their pre injury level of functional strength and have cosmetic deformity. Surgical management usually involves reattachment of the tendon to humerus by drill holes and tying sutures over a bone bridge[15] anchors[16-25], and staples[23]. Three main techniques of re-attachment of tendon to humerus are bone tunnel technique, bone trough technique and suture anchor technique. In bone tunnel technique sutures are passed using a curved suture passer through curved/angled bone tunnels and tendon are tied over a bone bridge reattaching the tendon to humerus. In bone trough technique drill holes are made into the bone trough at the site of tendon insertion. Suture anchors are being increasingly used in recent years, probably due to increasing familiarity of surgeons with these anchors and almost all the case series of repair with suture anchors have been reported after 2004[2,17-19,25]. Care should be taken not to injure the biceps tendon while making trough or drill holes in the bicipital groove.

Due to the rarity of injury no fixation method has been reported to give superior results compared to other methods, however drill holes fixation with or without trough remain the most common method of repair in most of the reported case series. Recently few cadaveric studies have given the results of biomechanical studies of common methods of pectoralis major repair. Sherman et al[21] and Hart et al[22] concluded that suture anchor repair and trans osseous repair of pectoralis major confer the same biomechanical integrity, whereas Rabuck et al[20] found a bone trough repair of the pectoralis major tendon was stronger than suture anchor repair. More studies are needed to reach a conclusion to recommend one method over another. We used suture anchors to fix the tendon to bone as these are easy to use and give firm anchorage in hard young cortical bone.

Although, excellent results have been reported in most cases of late presentation, the main differences in management of acute and chronic cases from the surgery point of view, is the available length of the tendon for repair. In a cadaveric study at our centre (unpublished data) we have seen that the approximate length of pectoralis major tendon from musculotendinous junction is 2.5 cm (Figure 7). In chronic cases the repairable length of the tendon is hardly available and it is mostly muscle/musculotendinous junction, which is anchored to bone (Figure 3). In our technique we used sliding knot, to prevent cutting through of suture through the muscle. Tendon mobilization may be a problem in chronic cases due to adhesions and scars. After incision of these peri-tendinous adhesions it may be possible to bring the tendon to the insertion site at humerus without tension[2]. If the sufficient excursion of the tendon is not possible use of allograft or autograft is necessary[24]. In our series we did not find any difficulty in the mobilization and fixation of pectoralis major tendon by corkscrew anchors and achieved excellent results.

The only limitation of this study is that the sample size is small, but due to the rarity of the tear of pectoralis major, results are worth reporting. As such, few cases of chronic tears have been reported and there is no consensus for a surgical repair method for chronic tears. We could conclude from this series that pectoralis major repair can be done even in chronic cases using 5.5 mm corkscrew anchors and it gives excellent functional and cosmetic results. Surgery should be done in all such active persons who want to get back to pre-injury activity level.

Pectoralis major tears are rare injuries with reporting of just over 350 cases in English literature. Pectoralis major muscle has 2 heads of origin, sternocostal and clavicular. The Sternocostal part is mainly internal rotator and adductor of the shoulder whereas the clavicular part is mainly forward flexor and adductor of the shoulder. Management of these tears has been changed over the years from conservative to surgical and now most of the pectoralis major tears are being managed surgically, especially in young athletes. Tears are classified into sprain, partial and complete tears. The most common type of complete tears are tears of tendon itself and tears at musculotendinous junction. Many surgical repair methods have been published for both acute and chronic cases with no published reports of superiority of one method over others.

In chronic retracted tear of the pectoralis major muscle, repairable length of the tendon is hardly available and mostly it is the musculotendinous unit which remains left. In these cases cutting of suture through the retracted musculotendinous unit is likely while pulling it towards the humerus. To overcome this difficulty the authors used specially designed box suture sliding technique with corkscrews.

Sliding knots with suture anchors are commonly used in arthroscopic surgeries. Their study describes the useful role of sliding knot and corkscrew suture anchors in repair of chronic tears of pectoralis major muscle.

The results of this study describe the valuable role of corkscrew suture anchors and sliding knot in repair of chronic tears of the pectoralis major.

The authors of this paper evaluated the results of repair of chronic tears of the pectoralis major muscle using corkscrews and a specially devised sliding knot in 11 patients. They obtained excellent results with significant improvement in ASES score, Penn score and isokinetic strength testing.

| 1. | Potter BK, Lehman RA, Doukas WC. Pectoralis major ruptures. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2006;35:189-195. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Petilon J, Carr DR, Sekiya JK, Unger DV. Pectoralis major muscle injuries: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tietjen R. Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. J Trauma. 1980;20:262-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hasegawa K, Schofer JM. Rupture of the pectoralis major: a case report and review. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hanna CM, Glenny AB, Stanley SN, Caughey MA. Pectoralis major tears: comparison of surgical and conservative treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:202-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Connell DA, Potter HG, Sherman MF, Wickiewicz TL. Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;210:785-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schepsis AA, Grafe MW, Jones HP, Lemos MJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:9-15. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bak K, Cameron EA, Henderson IJ. Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | ElMaraghy AW, Devereaux MW. A systematic review and comprehensive classification of pectoralis major tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | März J, Novotný P. [Pectoralis maior tendon rupture and anabolic steroids in anamnesis--a case review]. Rozhl Chir. 2008;87:380-383. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wolfe SW, Wickiewicz TL, Cavanaugh JT. Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:587-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aärimaa V, Rantanen J, Heikkilä J, Helttula I, Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1256-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, Rosenberg PH, Weisbort M, Hendel D. Pectoralis major rupture in elderly patients: a clinical study of 13 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;164-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kretzler HH, Richardson AB. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Castro Pochini A, Ejnisman B, Andreoli CV, Monteiro GC, Silva AC, Cohen M, Albertoni WM. Pectoralis major muscle rupture in athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:92-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merolla G, Campi F, Paladini P, Porcellini G. Surgical approach to acute pectoralis major tendon rupture. G Chir. 2009;30:53-57. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kakwani RG, Matthews JJ, Kumar KM, Pimpalnerkar A, Mohtadi N. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: surgical treatment in athletes. Int Orthop. 2007;31:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Samitier GS, Marcano AI, Farmer KW. Pectoralis major transosseous equivalent repair with knotless anchors: Technical note and literature review. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2015;9:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rabuck SJ, Lynch JL, Guo X, Zhang LQ, Edwards SL, Nuber GW, Saltzman MD. Biomechanical comparison of 3 methods to repair pectoralis major ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1635-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sherman SL, Lin EC, Verma NN, Mather RC, Gregory JM, Dishkin J, Harwood DP, Wang VM, Shewman EF, Cole BJ. Biomechanical analysis of the pectoralis major tendon and comparison of techniques for tendo-osseous repair. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1887-1894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hart ND, Lindsey DP, McAdams TR. Pectoralis major tendon rupture: a biomechanical analysis of repair techniques. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1783-1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Egan TM, Hall H. Avulsion of the pectoralis major tendon in a weight lifter: repair using a barbed staple. Can J Surg. 1987;30:434-435. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Zafra M, Muñoz F, Carpintero P. Chronic rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: report of two cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:107-110. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Mooers BR, Westermann RW, Wolf BR. Outcomes Following Suture-Anchor Repair of Pectoralis Major Tears: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:8-12. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fernandez-Fairen M, Madadi F S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ