Published online Sep 18, 2015. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.564

Peer-review started: April 1, 2015

First decision: June 3, 2015

Revised: June 17, 2015

Accepted: June 30, 2015

Article in press: July 2, 2015

Published online: September 18, 2015

Processing time: 170 Days and 7.3 Hours

Neuromuscular scoliosis is a challenging problem to treat in a heterogeneous patient population. When the decision is made for surgery the surgeon must select a technique employed to correct the curve and achieve the goals of surgery, namely a straight spine over a level pelvis. Pre-operatively the surgeon must ask if pelvic fixation is worth the extra complications and infection risk it introduces to an already compromised host. Since the advent of posterior spinal fusion the technology used for instrumentation has changed drastically. However, many of the common problems seen with the unit rod decades ago we are still dealing with today with pedicle screw technology. Screw cut out, pseudoarthrosis, non-union, prominent hardware, wound complications, and infection are all possible complications when extending a spinal fusion construct to the pelvis in a neuromuscular scoliosis patient. Additionally, placing pelvic fixation in a neuromuscular patient results in extra blood loss, greater surgical time, more extensive dissection with creation of a deep dead space, and an incision that extends close to the rectum in patients who are commonly incontinent. Balancing the risk of placing pelvic fixation when the benefit, some may argue, is limited in non-ambulating patients is difficult when the literature is so mottled. Despite frequent advancements in technology issues with neuromuscular scoliosis remain the same and in the next 10 years we must do what we can to make safe neuromuscular spine surgery a reality.

Core tip: We review the historical timeline of posterior spinal fusion in neuromuscular scoliosis. Over 30 years of treatment technology to treat scoliosis has changed drastically, however, we are still not without significant post-operative complications. Questioning how we treat neuromuscular scoliosis will hopefully push our community to advance our thought processes on this complex pathology and ultimately result in improved patient outcomes.

- Citation: Anari JB, Spiegel DA, Baldwin KD. Neuromuscular scoliosis and pelvic fixation in 2015: Where do we stand? World J Orthop 2015; 6(8): 564-566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v6/i8/564.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.564

Neuromuscular scoliosis is a very challenging problem to treat in a heterogeneous patient population. Of the many aspects that make the treatment of this disorder difficult are the ethical issues surrounding subjecting a frail debilitated patient to a large procedure that we believe will improve their seating comfort, pulmonary function, and quality of life[1,2]. These benefits are weighed against the risks of infection, pseudarthrosis, medical complications, cost, and implant related complications[2-4]. The decision of whether or not to proceed with surgical care is often quite difficult for families, and extensive discussions are often required.

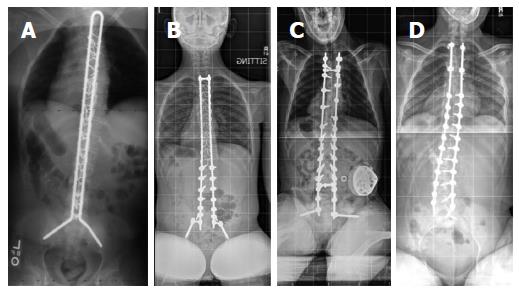

When the decision is made for surgery the surgeon must select a technique employed to correct the curve and achieve the goals of surgery, namely a straight spine over a level pelvis. There has been an evolution in implant design over the past few decades, and the traditional recommendation has been that the spinal instrumentation and fusion extend from the upper thoracic spine to the pelvis in non-ablulating patients. In the late 1970’s Allen and Ferguson described the Luque-Galveston technique, in which the distal end of each spinal rod was contoured to insert into the posterior ilium, extending towards the superior acetabulum. Contouring the rod distally was often a challenge and could be time consuming, leading to the development of the unit rod, in which both rods are included in a single, precontoured construct including the distal limbs which insert into the pelvis[5]. Either of these constructs achieved correction through cantilever bending, as the rod was initially attached to the pelvis and then maneuvered towards the spine while sequentially tightening sublaminar wires (Figure 1A). A constant challenge has been achieving arthrodesis at the lumbosacral junction, and pseudarthrosis resulted in “windshield wipering” of the pelvic limbs of the rod[6].

The next change in implant design was the advent of iliac screws (Figure 1B) which could be linked to the spinal rods through a cross connector. This increase in modularity occurred at the same time many surgeons began using pedicle screws in their constructs. An example is the “M-W” technique described by Arlet et al[7]. The basic philosophy for curve correction remained the same, although pedicle screw instrumentation with or without posterior osteotomies gave the surgeon a means to derotate the spine as a component of the corrective maneuver. The results in terms of control over pelvic obliquity seem to have been similar. Similar implant related complications have been observed with iliac bolts, namely failure at the connection point between the screw and the connector, or the rod and the connector, perhaps related to either pseudarthrosis or to the fact that the implants extend across a joint which is not fused (sacroiliac joint)[8].

In 2009, Chang et al[9] introduced the S2 alar iliac screw (Figure 1C), which can be directly linked to the spinal rod without a cross connector and without the wider exposure of the posterior ilium required to insert an iliac bolt or unit rod. Once again this modularity works well with constructs based on transpedicular fixation. The correction of pelvic obliquity with the S2 alar iliac screw is similar to that of the previous techniques.

Over the years we have learned from many “risk factors” studies that pelvic fixation itself is likely a risk factor for infection, which is one of the most dreaded (and common) complications of neuromuscular spine surgery[10]. The reasons for this may include extra blood loss, greater surgical time, more extensive dissection with creation of extra dead space, and an incision which extends closer to the rectum in patients who are commonly incontinent. This led McCall et al[11] to report on a series of patients using unit rod constructs with pedicle screws in the base ending at L5 in patients without severe pelvic obliquity (Figure 1D). This series showed similar control of curve parameters and pelvic obliquity as those fused across the lumbosacral joint. This series also demonstrated that the patients fixed to L5 had shorter operative times and fewer complications.

Although this approach in which the instrumentation and fusion are extended to the distal lumbar spine in patients without severe pelvic obliquity has not achieved wide acceptance to our knowledge, it certainly merits strong consideration, especially with an early diagnosis and adequate counseling of the family before the curves get to be severe and rigid. Is pelvic fixation really worth the extra complications and infection risk it introduces? While the literature mainly contains reports of radiographic outcomes and complications, there are no reports to our knowledge of patient or caregiver satisfaction with surgery or patient reported outcomes with any of the pelvic fixation techniques, let alone a report comparing the various methods.

The objectives of neuromuscular scoliosis surgery remain the same, to maintain adequate seating balance and prevent the complications associated with a progressive curvature. With more advanced techniques, our charge is to find a safer way to achieve this goal. While early diagnosis and treatment should certainly allow our constructs to end at L5, additional strategies including soft tissue release, posterior osteotomies, halopelvic traction, and VEPTR may be also used to achieve suitable correction to allow us to achieve this goal.

Despite numerous advancements in technology issues with neuromuscular scoliosis remain the same including: where does pelvic fixation fit in the treatment algorithm for neuromuscular scoliosis? We as a community should not shy away from questioning the dogma of fusing neuromuscular scoliosis patients to the pelvis as technology continues to change but complications persist without significant improvement in benefits. In the next 10 years we will answer these questions and more to make safe neuromuscular spine surgery a reality.

| 1. | Pehrsson K, Larsson S, Oden A, Nachemson A. Long-term follow-up of patients with untreated scoliosis. A study of mortality, causes of death, and symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17:1091-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mercado E, Alman B, Wright JG. Does spinal fusion influence quality of life in neuromuscular scoliosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:S120-S125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Benson ER, Thomson JD, Smith BG, Banta JV. Results and morbidity in a consecutive series of patients undergoing spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2308-2317; discussion 2318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalen V, Conklin MM, Sherman FC. Untreated scoliosis in severe cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:337-340. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bell DF, Moseley CF, Koreska J. Unit rod segmental spinal instrumentation in the management of patients with progressive neuromuscular spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:1301-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kuklo TR, Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Baldus C, Blanke K, Iffrig TM, Lenke LG. Minimum 2-year analysis of sacropelvic fixation and L5-S1 fusion using S1 and iliac screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1976-1983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arlet V, Marchesi D, Papin P, Aebi M. The ‘MW’ sacropelvic construct: an enhanced fixation of the lumbosacral junction in neuromuscular pelvic obliquity. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:229-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moshirfar A, Rand FF, Sponseller PD, Parazin SJ, Khanna AJ, Kebaish KM, Stinson JT, Riley LH. Pelvic fixation in spine surgery. Historical overview, indications, biomechanical relevance, and current techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87 Suppl 2:89-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chang TL, Sponseller PD, Kebaish KM, Fishman EK. Low profile pelvic fixation: anatomic parameters for sacral alar-iliac fixation versus traditional iliac fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:436-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ramo BA, Roberts DW, Tuason D, McClung A, Paraison LE, Moore HG, Sucato DJ. Surgical site infections after posterior spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis: a thirty-year experience at a single institution. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:2038-2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McCall RE, Hayes B. Long-term outcome in neuromuscular scoliosis fused only to lumbar 5. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2056-2060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Carter WG S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK