Published online Mar 18, 2015. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.316

Peer-review started: May 20, 2014

First decision: July 18, 2014

Revised: November 10, 2014

Accepted: November 17, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: March 18, 2015

Processing time: 303 Days and 18.4 Hours

Tuberculosis (TB) arthritis of the hip is a debilitating disease that often results in severe cartilage destruction and degeneration of the hip. In advanced cases, arthrodesis of the hip confers benefits to the young, high-demand and active patient. However, many of these patients go on to develop degenerative arthritis of the spine, ipsilateral knee and contralateral hip, necessitating the need for a conversion to total hip arthroplasty. Conversion of a previously fused hip to a total hip arthroplasty presents as a surgical challenge due to altered anatomy, muscle atrophy, previous surgery and implants, neighbouring joint arthritis and limb length discrepancy. We report a case of advanced TB arthritis of the hip joint in a middle-aged Singaporean Chinese gentleman with a significant past medical history of miliary tuberculosis and previous hip arthrodesis. Considerations in pre-operative planning, surgical approaches and potential pitfalls are discussed and the operative technique utilized and post-operative rehabilitative regime of this patient is described. This case highlights the necessity of pre-operative planning and the operative technique used in the conversion of a previous hip arthrodesis to a total hip arthroplasty in a case of TB hip arthritis.

Core tip: Different technical considerations regarding treatment of tuberculosis (TB) hip arthritis and various surgical techniques have been used in the surgical management of TB arthritis. This case report clearly illustrates the pre-operative planning, technical considerations and surgical technique used in the conversion of a arthrodesis into a total hip arthroplasty.

- Citation: Tan SM, Chin PL. Total hip arthroplasty for surgical management of advanced tuberculous hip arthritis: Case report. World J Orthop 2015; 6(2): 316-321

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v6/i2/316.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.316

Tuberculosis (TB), one of the most ancient diseases known to mankind, has remained a public health problem in both developing and developed countries. In 2011, 1533 new cases of TB were notified to the Ministry of Health, Singapore, representing 3.72% increase from the year before[1,2]. Correspondingly, the incidence rate increased from 39.2 cases per 100000 in 2010 to 40.5 cases per 100000 in 2011[2].

Extrapulmonary infection with Mycobacterium Tuberculosis has musculoskeletal involvement in up to 19% of cases[3,4] with the spine being the most common skeletal site (50%)[5]. This is followed by the pelvis (12%), hip, knee and tibia (10% each)[5].

TB arthritis of the hip in young individuals are often treated conservatively with physiotherapy, analgesia and rest. In advanced cases, arthrodesis of the hip confers benefits to the young, high-demand and active patient[6,7]. However, many of these patients go on to develop degenerative arthritis of the spine, ipsilateral knee and contralateral hip[8], necessitating the need for a conversion to total hip arthroplasty.

We report a case of advanced TB arthritis of the hip joint in a middle-aged Singaporean Chinese gentleman with a significant past medical history of miliary tuberculosis and previous hip arthrodesis. He presented with an indolent course of low-grade right hip pain for four months associated with symptomatic degenerative arthritis of the spine.

A 51-year-old Chinese Singaporean male mechanic, with a past medical history of miliary tuberculosis complicated by TB peritonitis, left renal pyelonephritis and right hip TB arthritis, presented with right hip pain of four months. This was associated with a complaint of lower back pain. He had previously undergone a right hip synovectomy and a right hip arthrodesis at the respective ages of 2 and 22. In the index hip surgery where synovectomy was performed, tissue sample sent for acid-fast bacilli smears was positive. He was also treated with a course of anti-tuberculous therapy. No subsequent episodes of reactivation were noted. Over an 8-mo period from the time of presentation, he was found to have gradual worsening of symptoms. Subsequently he developed an antalgic gait and experienced difficulty with climbing stairs. A course of conservative treatment including analgesia with physiotherapy did not alleviate his symptoms. There were no recent respiratory symptoms, fever or trauma. No recent travel was noted.

Clinical examination of the right hip revealed generalized tenderness of the right groin with limited range of motion. Hip flexion was restricted to 20°, hip extension to 10° with minimal abduction, adduction, external and internal rotation. A previous surgical scar was seen on the posterior aspect of the right hip. The patient did not have any neurovascular deficit.

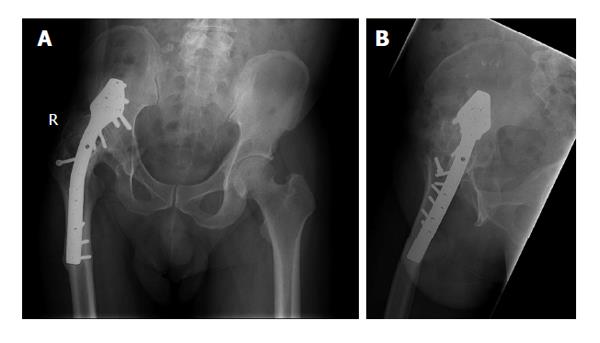

Initial radiographs (Figure 1) done of the pelvis and right hip showed minimal right hip fusion with the presence of a Cobra plate used for hip arthrodesis. In addition, there was evidence of screw loosening and breakage seen on the initial radiographs. Based on the Martini et al[9] radiographic classification, this patient has Stage III TB arthritis. His inflammatory markers were not elevated with a total white cell count of 6.1 × 109 with no neutrophilic shift. C-reactive protein was not elevated.

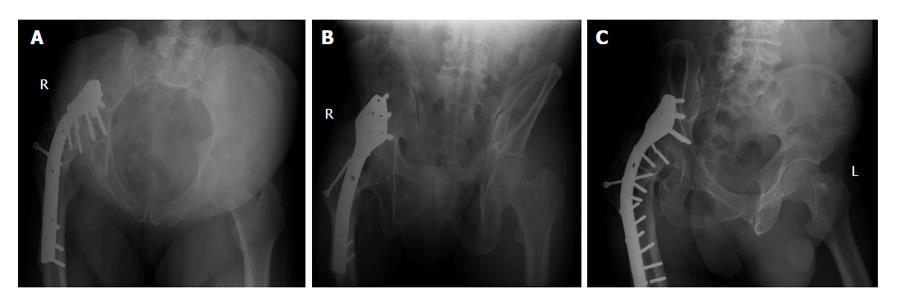

Despite conservative measures, he continued to experience pain in his right hip and lower back, limiting his ability to work. Repeat radiographs done at 5-mo interval (Figure 2) showed further loosening and breakage of the screws. As the inflammatory markers did not show an active infection and the patient did not have any infective symptoms such as fever, no specimens were sent for histological or bacteriological investigations.

The patient underwent removal of right femur cobra plate and a cementless right total hip arthroplasty at 8-mo follow-up after failed conservative therapy. Intraoperative findings included a fused right hip with Cobra plate failure and multiple broken screws. Specimen were taken intraoperatively and sent for microscopy, acid-fast bacilli smears and cultures. These tests returned with negative results.

In our reported case, a direct posterolateral incision was first made and the fascia split before lifting up the vastus lateralis to take down the Cobra plate and broken screws from the previous arthrodesis. This approach was favored because this it was used by the previous surgeon and offers the most direct surgical access to the existing implants. Adopting a different exposure is likely to result in greater tissue damage leading to greater risk of dislocation in an inherently unstable hip. Subsequently, a modified anterior approach was used primarily for the following reasons: (1) to preserve the weak abductors; (2) to remove all broken screws via a femoral window; and (3) to confer maximal hip stability by reducing the likelihood of posterior hip dislocation. A long cortical window was made in order to assess and remove the previous prosthesis. Upon complete removal of previous prosthesis, release of the soft tissue envelope was performed-gluteus maximus attachment to femur, ilio-psoas and the anterior capsule.

We proceeded to obtain bony landmarks using guide-wires placed in the femoral neck for the femoral neck osteotomy. These landmarks were checked with an image intensifier. It is imperative that a pre-procedure radiographic image is performed to have a complete view of the hip joint. Subsequently, we performed the femoral neck osteotomy with a saw followed by posterior capsule release.

Identification of the true acetabulum was achieved by using the following prominent landmarks such as the fovea, transverse acetabular ligament, greater sciatic notch and pubic rami. The anatomical position of the true acetabulum can be further ascertained intra-operatively with the use of the image intensifier. Once the true acetabulum position has been ascertained, we deepened and enlarged the acetabulum progressively, beginning with the smallest-sized acetabular reamer and continuing till both the medial wall and floor of the acetabulum were encountered. In our reported case, the joint fusion was largely fibrous and this allowed a distinct envelope to be identified. We chose a TM acetabular cup and screw fixation. The choice of fixation was made with the consideration that the acetabulum was osteoporotic likely from stress shielding. In addition, in this inherently unstable hip joint, the possibility of conversion to a constrained hip prosthesis can be considered in a subsequent procedure.

The approach for the femoral component is similar to a conventional total hip arthroplasty. Key to this step was the release of soft tissue releases and their reattachment. As we have a long cortical window from the removal of the broken screws, a fully-beaded, coated, long bow stem was used to bypass the window. The use of defunctioning wires distal to the cortical window prevented propagation of a potential femur split. A bow stem was selected in order to achieve better rotational control of the femoral stem. A large, 32-mm diameter head was used to increase the stability with an ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene liner. Meticulous inspection for bony impingements was done and any impingement was chilectomized.

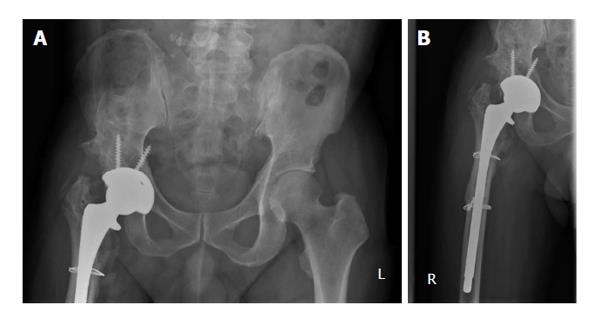

Post-operative radiographs at 4-mo interval (Figure 3) showed good anteversion of the acetabular component with bony ingrowth, no evidence of femoral or acetabular component loosening and no evidence of limb length discrepancy.

Postoperatively, this patient was started on a progressive rehabilitation regime, beginning with limited range of motion exercises. He was placed on a hip brace and started on partial-weight bearing exercises with the use of a walking frame for 6 wk post-operatively. Subsequently, he began full-weight bearing exercises. At 3-mo follow up interval, he was able to ambulate without any walking aids. He had no more complaints of right hip pain or lower back pain. On examination, he no longer exhibits an antalgic gait and shows significant improvement in hip abduction and external rotation movements. No significant limb length discrepancy was noted.

Using the Oxford Hip Questionnaire[10], the patient had an improved score of 17 post-operatively compared to 22 pre-operatively. The patient also had improved scores in terms of pain, stiffness and physical function based on WOMAC Arthritis Questionnaire.

TB arthritis of the hip is a very disabling disease. Known for its insidious onset, lack of early characteristic radiographic findings and often lack of constitutional or pulmonary involvement, it presents a diagnostic challenge for the orthopaedic surgeon.

The potential risk of reactivation has led to the controversy surrounding the timing of total hip arthroplasty and the use of anti-tuberculous chemotherapy. Whilst some authors advocated the use of anti-tuberculous therapy in prevention of TB reactivation, most authors did not routinely use anti-tuberculous therapy in managing these patients pre- and post-operatively. Two key factors for TB reactivation were identified: (1) the period of quiescence from the initial infection till the time of surgery; and (2) complete curettage and debridement of infected tissue. Hardinge et al[11] reported 21 cases of TB hip arthritis treated with total hip arthroplasty with quiescent periods between active infection and time of surgery ranging from 1 to 20 years. In this series where no chemoprophylaxis was given, no recurrence was reported. Similarly, Eskola et al[12] reported no recurrence in 18 patients who underwent cementless total hip arthroplasty for TB hip arthritis. Anti-tuberculous therapy was used in only 7 of these patients and surgery was performed on an average of 34 years from the time of onset. A study done by Joshi et al[13] in 2002 also showed no reactivation of tuberculosis in 60 patients who had hip arthrodesis converted to total hip arthroplasty. The mean time interval between hip fusion and conversion to total hip arthroplasty was 27 years. Oztürkmen et al[14] advocated the use of 1-year anti-tuberculous therapy post-operatively. In this series of 12 patients, none had TB recurrence.

In the case reported, the time of total hip arthroplasty was 49 years after the initial onset of infection which provides a significant quiescent time interval between active infection and arthroplasty. The time interval between arthrodesis to conversion to total hip arthroplasty was 29 years. Furthermore, the inflammatory markers were not elevated and intraoperative cultures were negative for acid-fast bacilli, hence anti-tuberculous chemotherapy was not instituted prophylactically both pre-operatively and post-operatively.

Conversion total hip arthroplasty from hip arthrodesis is a surgical challenge and have been reported to have high complication rates[15-17]. The initial work-up requires the careful exclusion of an active tuberculous reactivation of joint infection. This can be achieved with the use of serial inflammatory markers, tissue and blood cultures. An assessment of the gluteus muscles to evaluate abductor muscles function is key to predicting implant stability post-operatively[18]. The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) stands superior to ultrasound evaluation of the glutei muscles. The presence of fatty degeneration within the glutei muscles often indicates permanent disability. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography further compliment this assessment. Another important consideration is that of limb length discrepancy[19] that often presents post-operatively due to the massive shortening of the affected limb. Depending on the amount of discrepancy, measures ranging from the use of platform shoes to shortening osteotomy of the contralateral limb may be necessary to correct the deficit.

In terms of surgical exposure, difficulties include utilizing an approach that facilitates minimal damage to the atrophied abductor muscles, osteotomy to take down the arthrodesis, delivering femur out of the wound with minimal soft tissue trauma, determining the site and depth of the true acetabulum, altered positions of anatomical landmarks, reconstruction of the abductor mechanism, stability, limb length discrepancy and post-operative rehabilitation of the abductor muscles. Other important factors that mitigate the decision for a particular approach include previous surgical exposure, stability of the prosthesis and the need for removal of any existing implants.

In a study in done in 2007, Morsi[19] used a trans-trochanteric approach in 19 cases undergoing conversion to total hip arthroplasty from previous hip arthrodesis. He cited 4 reasons for using such an approach: (1) to facilitate the procedure; (2) to preserve the weak abductors; (3) the greater trochanter may be over the axis of entry of the femoral component into the medullary canal as a result of previous arthrodesis; and (4) trochanteric advancement was required to adjust the tension of the abductors for better stability and function. At a mean of 7.1 years follow-up, 1 out of 19 cases had failed. This was a result of recurrent dislocation which required revision.

Correction of limb length discrepancy is important in the alleviation of lower back pain, restoration of normal gait pattern and prevention of scoliosis. It is critical to note that in patients who have had fused hips for long periods, a significant correction of limb length discrepancy may result in exacerbation of back pain due to fixed obliquity of the pelvis and scoliosis[19]. Optimal correction of the limb length discrepancy should be based on the mobility of both pelvis and lower back.

Conversion of a fused hip should be performed by an experienced surgeon well versed in the different surgical approaches and techniques to the hip. The procedure may potentially involve large amounts of blood loss and prolonged operative timing. As such, the use of mechanical foot pumps, warming blankets and cell savers are measures that should be considered in the prevention of deep venous thrombosis, hypothermia and significant hemorrhage.

This case highlights the necessity of pre-operative planning and the operative technique used in the conversion of a previous hip arthrodesis to a total hip arthroplasty in a case of TB hip arthritis.

A 51-year-old Chinese Singaporean male mechanic, with a past medical history of miliary tuberculosis complicated by tuberculosis (TB) peritonitis, left renal pyelonephritis and right hip TB arthritis, presented with right hip pain of four months.

Hip arthritis.

Tuberculous hip arthritis, osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis.

Inflammatory markers were not elevated with a total white cell count of 6.1 × 109 with no neutrophilic shift. C-reactive protein was not elevated.

Radiographs done of the pelvis and right hip showed right hip fusion with the presence of a Cobra plate used for hip arthrodesis. In addition, there was evidence of screw loosening and breakage. Based on the Martini and Ouaches radiographic classification, this patient has Stage III TB arthritis.

Tissue samples were taken intraoperatively and sent for microscopy, acid-fast bacilli smears and cultures, which returned with negative results.

The patient underwent removal of right femur cobra plate and a cementless right total hip arthroplasty at 8-mo follow-up after failed conservative therapy.

Eskola et al reported no TB recurrence in 18 patients who underwent cementless total hip arthroplasty for TB hip arthritis. Joshi et al also showed no reactivation of tuberculosis in 60 patients who had hip arthrodesis converted to total hip arthroplasty. Conversion total hip arthroplasty from hip arthrodesis is a surgical challenge and have been reported to have high complication rates as reported by Kreder et al and Strathy et al in their respective studies on patients with ankylosed hips undergoing total hip arthroplasty.

Arthrodesis, also known as fusion of the joint, is commonly performed for young patients with TB hip arthritis. This often results in limited range of motion of the affected hip joint. Conversion to total hip arthroplasty in which the fused joint is taken down and implanted with both an acetabular and femoral component to increase the range of motion of the hip joint and provide a better functional outcome, especially for the young, high-demand patients.

This case highlights the necessity of pre-operative planning and the operative technique used in the conversion of a previous hip arthrodesis to a total hip arthroplasty in a case of TB hip arthritis.

The case report by Tan and Chin is well done and highlights an important operative technique that makes a big difference in patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis with skeletal involvement, specifically hip involvement.

| 1. | World Health Organization. TB factsheet. Tuberculosis Profile for Singapore. Available from: http:// www.who.int/tb/data. |

| 2. | Ministry of Health, Singapore. Update on the Tuberculosis Situation in Singapore. 2012; Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/pressRoomItemRelease/2012/stop_TB_in_my_lifetime.html. |

| 3. | Watts HG, Lifeso RM. Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:288-298. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ruiz G, García Rodríguez J, Güerri ML, González A. Osteoarticular tuberculosis in a general hospital during the last decade. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:919-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pasion EG, Leung JP. TB Arthritis. Current Orthopaedics. 2000;14:197-204. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Callaghan JJ, Brand RA, Pedersen DR. Hip arthrodesis. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1328-1335. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sponseller PD, McBeath AA, Perpich M. Hip arthrodesis in young patients. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:853-859. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Roberts CS, Fetto JF. Functional outcome of hip fusion in the young patient. Follow-up study of 10 patients. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Martini M, Ouahes M. Bone and joint tuberculosis: a review of 652 cases. Orthopedics. 1988;11:861-866. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Amstutz HC, Sakai DN. Total joint replacement for ankylosed hips. Indications , technique, and preliminary results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:619-625. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hardinge K, Cleary J, Charnley J. Low-friction arthroplasty for healed septic and tuberculous arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61-B:144-147. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Eskola A, Santavirta S, Konttinen YT, Tallroth K, Hoikka V, Lindholm ST. Cementless total replacement for old tuberculosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:603-606. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Joshi AB, Markovic L, Hardinge K, Murphy JC. Conversion of a fused hip to total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1335-1341. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Oztürkmen Y, Karamehmetoğlu M, Leblebici C, Gökçe A, Caniklioğlu M. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for the management of tuberculosis coxitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:197-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kreder HJ, Williams JI, Jaglal S, Axcell T, Stephen D. A population study in the Province of Ontario of the complications after conversion of hip or knee arthrodesis to total joint replacement. Can J Surg. 1999;42:433-439. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Strathy GM, Fitzgerald RH. Total hip arthroplasty in the ankylosed hip. A ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:963-966. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kilgus DJ, Amstutz HC, Wolgin MA, Dorey FJ. Joint replacement for ankylosed hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:45-54. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Springer I, Müller M, Hamm B, Dewey M. Intra- and interobserver variability of magnetic resonance imaging for quantitative assessment of abductor and external rotator muscle changes after total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morsi E. Total hip arthroplasty for fused hips; planning and techniques. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:871-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Ayieko J, Drain P, Garcia-Elorriaga G, Silva GAV

S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/