Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.110188

Revised: June 15, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 224 Days and 0.7 Hours

The optimal surgical approach for patients with primary glenohumeral osteo

To systematically compare the outcomes of RTSA and TSA in this specific patient population.

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Retrospective comparative studies evaluating RTSA and TSA in patients with GHOA and intact rotator cuff were included. Key outcomes assessed included complication and reoperation rates, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and range of motion. Risk of bias was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool.

Twelve studies encompassing 1608 patients (580 RTSA, 1028 TSA) met inclusion criteria. RTSA was associated with a lower reoperation rate compared to TSA [odds ratio = 0.37; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.14-0.94; P value = 0.04], while no significant difference in overall complication rates was observed (odds ratio = 0.47; 95%CI: 0.19-1.16; P value = 0.10). RTSA patients showed superior outcomes in University of California Los Angeles, Simple Shoulder Test, and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index scores; however, the differences did not exceed the minimal clinically important difference. TSA patients had significantly better external rotation (mean difference= -9.0°; 95%CI: -13.21 to -5.02; P value < 0.0001). No significant differences were found in other range of motion measures or satisfaction scores. The overall methodological quality of included studies was moderate to serious.

In patients with GHOA and an intact rotator cuff, RTSA may offer comparable or improved outcomes to TSA with lower reoperation rates and similar complication profiles. Functional outcomes favour RTSA in certain patient-reported outcome measures, while TSA retains an advantage in external rotation. Surgical decision-making should remain individualized based on patient characteristics and functional demands.

Core Tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis compares reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) and total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) in patients with primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis and an intact rotator cuff. Analyzing 1608 patients across 12 studies, we found RTSA was associated with lower reoperation rates and similar complication profiles compared to TSA. While TSA demonstrated better external rotation, RTSA showed favourable patient-reported outcomes, though most did not exceed clinical relevance thresholds. These findings support RTSA as a viable alternative in select patients, challenging traditional treatment paradigms and guiding individualized surgical decision-making.

- Citation: Desouza C, Siddique I, Kushwaha K, Puri A. Outcomes of reverse vs anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty in glenohumeral osteoarthritis without rotator cuff deficiency: A meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 110188

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/110188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.110188

Anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse TSA (RTSA) have become increasingly common surgical options for managing primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis (GHOA). Both procedures have shown efficacy in alleviating pain and improving shoulder function[1]. Traditionally, the choice between TSA and RSA has largely depended on the condition of the rotator cuff[2,3]. A deficient rotator cuff can lead to biomechanical dysfunction, including superior migration of the humeral head, which negatively affects joint mechanics and increases stress on implant components. This stress may manifest as edge loading and glenoid component wear, commonly referred to as the “rocking-horse phenomenon”[4,5].

Long-term outcomes have raised concerns regarding the durability of TSA in the context of rotator cuff integrity. For instance, secondary rotator cuff dysfunction has been observed in a significant proportion of patients following TSA[6,7]. One study reported a 16.8% incidence of such dysfunction at an average of 8.6 years postoperatively, which correlated with both poorer clinical outcomes and adverse radiographic findings[8]. Consequently, rotator cuff failure remains a leading cause of TSA revision.

Given these considerations, RTSA is often favoured in certain patient populations -particularly those with diminished tissue quality, advanced age, lower activity levels, or complex glenoid anatomy. However, identifying patients at high risk for poor outcomes following TSA remains challenging due to the subjective and variable nature of these risk factors. This uncertainty has contributed to an increasing trend toward selecting RTSA for GHOA even when the rotator cuff is intact, in an effort to reduce reliance on cuff functionality and avoid future complications.

Although RTSA is primarily approved for cases involving cuff tear arthropathy, its use has expanded to include primary GHOA in patients with preserved rotator cuffs. This shift in practice patterns has prompted ongoing debate regarding the relative benefits and risks of TSA vs RTSA in this context. The first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic, conducted by Kim et al[9] in 2022, included six studies comprising 447 patients with intact rotator cuffs that reported broadly equivalent functional outcomes, but with limited scope. In contrast, our study includes 12 studies encompassing over 1600 patients, integrates new outcome measures, and offers updated comparative data. This more comprehensive review aims to better inform clinical decision-making by evaluating not only complications and functional scores but also range of motion (ROM) and revision rates.

Since then, multiple new comparative studies have been published, offering conflicting evidence regarding complications, functional outcomes, and reoperation rates[3,10,11]. To synthesize this emerging evidence and inform clinical decision-making, we conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on patients with primary GHOA and intact rotator cuffs. Specifically, we sought to answer three key questions: (1) Which procedure is associated with a higher rate of perioperative complications? (2) Which offers superior postoperative patient-reported outcomes? and (3) Which results in better postoperative ROM?

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines[12]. A comprehensive literature search was carried out across three major databases: PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. The search conducted between January 2015 to December 2024 employed a combination of relevant keywords and Boolean operators, including “reverse”, “osteoarthritis”, “shoulder”, “arthroplasty”, and “replacement” to identify studies comparing RTSA with TSA in the setting of primary GHOA with an intact rotator cuff. Additional studies were identified by manually reviewing reference lists from selected articles and through targeted internet searches. Study selection was initially performed by one reviewer and subsequently verified by a second reviewer. The study selection process is illustrated in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria consisted of comparative studies assessing RTSA vs TSA in patients with primary GHOA and intact rotator cuffs. Studies were excluded if they were non-comparative, utilized national databases (to minimize potential patient overlap), or involved additional surgical interventions alongside TSA, such as posterior capsular plication.

Two independent reviewers screened studies for eligibility and extracted relevant data. Extracted variables included adverse events (perioperative complications and reoperations), patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) such as satisfaction, Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) - with higher scores indicating worse outcomes for VAS and SPADI - as well as the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, Constant Score (CS), and Simple Shoulder Test (SST), where higher scores indicate better function. ROM data were also collected, including external rotation (ER), internal rotation (IR), forward flexion, and abduction. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus.

The risk of bias for non-randomized studies was evaluated using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool by two reviewers independently[13]. Studies assessed as having a critical risk of bias were excluded from the analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, United Kingdom). Continuous outcomes were analyzed using mean differences (MD) or standardized MD, each with 95% confidence interval (CI). Dichotomous outcomes were evaluated using odds ratios (OR). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed with the Q statistic and I2 index. A random-effects model was applied when significant heterogeneity was present, while a fixed-effect model was used in cases of low heterogeneity. Additionally, the distribution of Walch glenoid classifications between TSA and RTSA groups was compared using χ2 analysis via SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Twelve retrospective studies met the inclusion criteria[14-25], encompassing a total of 1608 patients - 580 in the RTSA group (36.06%) and 1028 in the TSA group (63.94%). The key characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

| Ref. | Study | Participants | Age (years) | Mean follow-up | Glenoid morphology | Adverse events | |||||

| RTSA | TSA | RTSA | TSA | RTSA | TSA | RTSA | TSA | RTSA | TSA | ||

| Ardebol et al[14], 2024 | Retrospective | 37 | 67 | 80 | 79 | 33 months | 43 months | 8 A14 A22 B123 B2/B3 | 28 A13 A221 B115 B2/B3 | 1 stiffness 1 acromial stress fracture | 3 rotator cuff failure 2 stiffness |

| Haritinian et al[15], 2020 | Retrospective | 12 | 39 | 71 | 68 | - | 3 A11 A22 B16B2/B3 | 13 A16 A213 B17 B2/B3 | - | - | |

| Hones et al[16], 2024 | Retrospective | 60 | 60 | 72 | 70 | 3.7 years | 4.0 years | - | - | - | |

| Kim[17], 2024 | Retrospective | 26 | 41 | 75 | 76 | 45 months | 39 months | 16A15A24B11B2 | 31 A17A21B12B2 | 1 infection | 1 rotator cuff tear with glenoid loosening |

| Kirsch et al[18], 2022 | Retrospective | 67 | 67 | 67 | 27 months | 33 months | 17 A17A24 B134 B2/B33C2D | 25 A11A23B134B2/B33C1D | 1 acromial stress fracture 1 glenoid fracture 1 radial nerve palsy | 1 rotator cuff tear, 1 ulnar nerve palsy 1 hematoma | |

| Mahylis et al[19], 2024 | Retrospective | 149 | 187 | 71 | 66 | 41 months | 62 months | - | 1 glenoid loosening | 11 glenoid loosening 3 nonspecified | |

| Merolla et al[20], 2020 | Retrospective | 36 | 47 | 72 | 2.4 years | - | 2 diaphyseal fractures | 1 rotator cuff tear | |||

| Polisetty et al[21], 2021 | Retrospective | 63 | 252 | 74 | 73 | 3.8 years | 2A17A22B137B2/B32C13D | 81 A147A214 B197B2/31C12D | - | 5 rotator cuff tears (with 2 glenoid loosening) 1 infection with glenoid loosening 5 glenoid loosening | |

| Steen et al[22], 2015 | Retrospective | 24 | 96 | 78 | 77 | 3.5 years | 7A15A21B18B23C | 28A120A24B132B212C | 1 periprosthetic fracture | 5 glenoid loosening | |

| Trammell et al[23], 2023 | Retrospective | 64 | 64 | 72 | 68 | 3 years | 5 years | - | 1 component failure 1 glenoid fracture 2 periprosthetic fractures 2 intraoperative fractures | 4 glenoid loosening 1 humeral loosening 1 humeral and glenoid loosening 1 component failure 3 infections 1 periprosthetic fracture 2 unexplained pain | |

| Turnbull et al[24], 2024 | Retrospective | 9 | 46 | 71 | 67 | - | - | 1 glenoid fracture | 6 glenoid loosening 2 component failures 1 glenoid and humeral loosening 1 infection1 glenoid fracture 1 periprosthetic fracture 1 unexplained pain | ||

| Wright et al[25], 2020 | Retrospective | 33 | 102 | 77 | 6 years | - | 1 infection 1 fracture 1 nerve palsy 1 vascular injury | 11 rotator cuff tears 2 fractures 1 recurrent dislocation | |||

All 12 studies reported data on patient age and follow-up duration. Patients undergoing RTSA were significantly older than those receiving TSA, with a MD of 1.73 years (95%CI: 0.48-2.99; P value = 0.007; Figure 2A). Additionally, the RTSA group had a significantly shorter follow-up duration by a mean of 8.83 months (95%CI: -15.93 to -1.74; P value = 0.01; Figure 2B).

Eight studies (n = 888; 381 RTSA, 507 TSA) reported preoperative Walch glenoid classifications. A significant difference in glenoid morphology was observed between the groups. The TSA cohort predominantly exhibited type A glenoid, while the RTSA cohort demonstrated a greater prevalence of complex morphologies, including types B, C, and D (Table 2). These anatomical differences likely influenced surgical decision-making and may have impacted clinical outcomes.

| Walch type | RTSA (n = 381) | TSA (n = 507) |

| Type A1 | 53 | 206 |

| Type A2 | 29 | 84 |

| Type B1 | 15 | 66 |

| Type B2/B3 | 108 | 175 |

| Type C | 8 | 16 |

| Type D | 15 | 13 |

A subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the association between preoperative glenoid morphology and the likelihood of undergoing RTSA vs TSA. Patients with more complex glenoid types - specifically Walch types B2/B3 and

Risk of bias was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool. While no study was deemed to have a critical risk of bias necessitating exclusion, the overall methodological quality varied. Most studies exhibited moderate to serious risk of bias in at least one domain, particularly in confounding and outcome measurement. These limitations underscore the importance of interpreting pooled results with caution (Table 3).

| Ref. | Bias due to confounding | Bias in selection of participants | Bias in classification of interventions | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing data | Bias in measurement of outcomes | Bias in selection of reported result | Overall risk of bias |

| Ardebol et al[14], 2024 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Haritinian et al[15], 2020 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Hones et al[16], 2024 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kim[17], 2024 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kirsch et al[18], 2022 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Mahylis et al[19], 2024 | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

| Merolla et al[20], 2020 | Serious | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Serious |

| Polisetty et al[21], 2021 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Steen et al[22], 2015 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Trammell et al[23], 2023 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Turnbull et al[24], 2024 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Wright et al[25], 2020 | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Serious |

Complication rates: Ten studies (n = 1477; 508 RTSA, 969 TSA) reported data on complications (Table 4). The pooled analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in complication rates between the RTSA and TSA groups (OR = 0.47; 95%CI: 0.19-1.16; P value = 0.10). While the point estimate favoured RTSA, the CI crossed the line of no effect. Moderate heterogeneity was noted (I2 = 58%) (Figure 4A).

| Complication | RTSA | % | TSA | % |

| Glenoid-related | ||||

| Glenoid fracture | 3 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Glenoid loosening | 1 | 0.2% | 37 | 3.6% |

| Dislocation | - | - | 1 | 0.1% |

| Humeral-related | ||||

| Humeral loosening | - | 0.0% | 3 | 0.3% |

| Diaphyseal fracture | 3 | 0.5% | - | - |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 3 | 0.5% | 2 | 0.2% |

| Unspecified fractures | - | - | 2 | 0.2% |

| Intraoperative fractures | 2 | 0.3% | - | - |

| Rotator cuff/soft tissue | ||||

| Rotator cuff tear/failure | - | - | 22 | 2.1% |

| Acromial stress fracture | 2 | 0.3% | - | - |

| Stiffness | 1 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.2% |

| Neurologic/vascular | ||||

| Nerve palsy | 2 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Vascular injury | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Infectious | ||||

| Infection | 1 | 0.2% | 5 | 0.5% |

| PJI | 3 | 0.5% | 3 | 0.3% |

| Hematoma | - | - | 1 | 0.1% |

| Implant-related | ||||

| Component failure | 1 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.3% |

| Broken baseplate screw | 1 | 0.2% | - | - |

| Other/unexplained | ||||

| Unexplained pain | 1 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.3% |

| Total complications | 28 | 4.8% | 103 | 10.0% |

Reoperation rates: The same ten studies also reported reoperation rates. RTSA was associated with significantly lower odds of reoperation compared to TSA (OR = 0.37; 95%CI: 0.14-0.94; P value = 0.04), with low between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 22%) (Figure 4B).

Four studies (n = 639; 282 RTSA, 357 TSA) reported SPADI and UCLA scores, while five studies (n = 759; 306 RTSA, 453 TSA) reported SST scores. Compared to TSA, the RTSA group showed: Lower SPADI scores (MD = -7.21; 95%CI: -14.10 to -0.33; P = 0.04) (Figure 4C), Higher UCLA scores (MD = 3.13; 95%CI: 0.90-5.36; P = 0.006) (Figure 4D), and Higher SST scores (MD = 0.65; 95%CI: 0.03-1.28; P = 0.04) (Figure 4E). No significant differences were observed between groups in patient satisfaction (Figure 4F), VAS (Figure 4G), ASES (Figure 4H), or CS (Figure 4I).

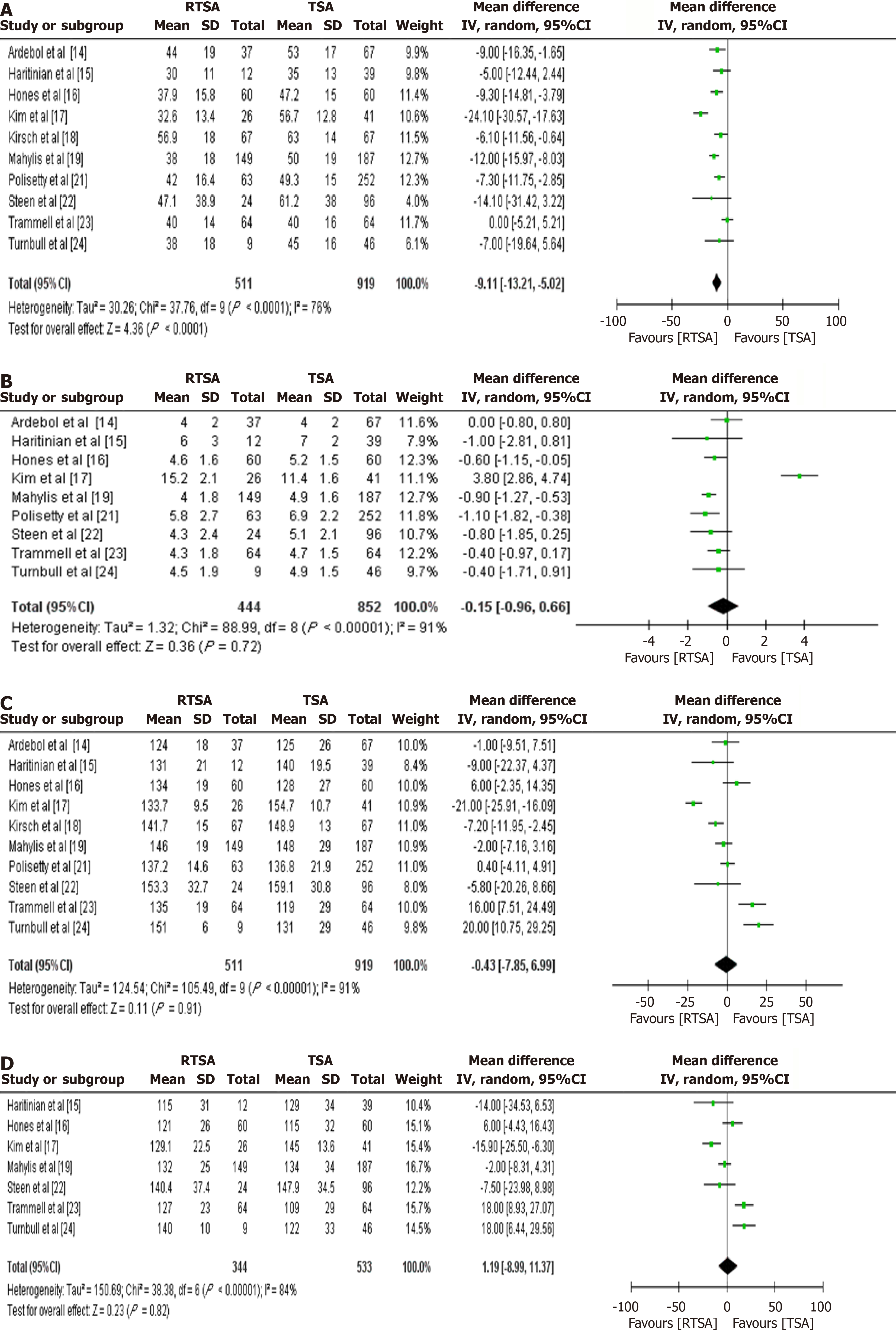

Ten studies (n = 1430; 511 RTSA, 919 TSA) reported ROM data: ER was significantly reduced in the RTSA group (MD =

As RTSA gains popularity and its indications expand, particularly in cases of GHOA with an intact rotator cuff, its comparative efficacy vs TSA warrants thorough evaluation. Historically, TSA has been the standard treatment in such cases; however, emerging literature supports RTSA as a viable alternative. This meta-analysis, comprising 12 comparative studies, provides new insights by demonstrating that RTSA is associated with lower rates of complications and reoperations, along with better outcomes in select patient-reported measures, including UCLA, SST, and SPADI scores.

Selection bias is a key limitation, as the RTSA cohort was significantly older (MD = 1.73 years) and had a shorter follow-up duration (MD = -8.83 months). These factors may have influenced outcomes such as complication and reoperation rates. Specifically, the lower reoperation rate observed in RTSA (OR = 0.37; P = 0.04) must be interpreted cautiously, as longer follow-up in the TSA group could allow more time for adverse events to accumulate. Prior literature, including work by Valsamis et al[26], suggests that differences in revision rates may diminish over extended follow-up periods - an important consideration not fully addressed in prior analyses.

Additionally, confounding due to glenoid morphology is another important factor. Table 2 highlights that TSA patients had a higher prevalence of Walch type A glenoid, whereas RTSA patients presented with more complex morphologies (types B2, B3, and D). These anatomical differences likely influenced surgical selection and may independently impact outcomes such as ROM and implant longevity. A subgroup analysis or meta-regression would help determine the independent effect of glenoid type on clinical outcomes.

Despite patients in the TSA group being, on average, younger, they experienced a higher incidence of complications and reoperations. These findings differ from those reported by Kim et al[9], who included fewer studies and incorporated one comparing TSA with posterior capsular plication - potentially introducing heterogeneity in their analysis.

Several factors may contribute to the observed differences in adverse events. One such factor is the evolving perception and application of RTSA. Historically viewed as a salvage option, RTSA is now increasingly used as a primary intervention for GHOA. This shift may alter revision thresholds and affect complication reporting. Notably, glenoid loosening and rotator cuff failure were among the most frequent complications in TSA, while RTSA's design, which relies on the deltoid rather than the rotator cuff, may inherently reduce the likelihood of such failures.

However, the longer mean follow-up duration in TSA patients (approximately 9 months more) could potentially bias comparisons of complication and revision rates. Moreover, the relatively short overall follow-up period limits conclusions regarding long-term outcomes. Prior studies, such as that by Valsamis et al[26], have indicated that differences in revision rates between RTSA and TSA may diminish with extended follow-up.

Regarding PROMs, RTSA was associated with significantly better SPADI, SST, and UCLA scores. However, caution is warranted in interpreting these differences. The improvements, although statistically significant, did not exceed the minimal clinically important differences for these scales - suggesting that the observed differences may not be clinically meaningful. Furthermore, these findings were based on a smaller subset of the included studies, whereas more commonly reported measures such as ASES and CSs showed no significant differences between groups.

In terms of ROM, TSA was superior in ER, with a MD of 9 degree, which does exceed the established minimal clinically important difference and aligns with findings from previous research. This difference is likely due to the distinct biomechanical designs of the two prosthetic systems. Other motion parameters, including IR, forward flexion, and abduction, did not differ significantly between groups.

This meta-analysis offers several strengths, including a comprehensive review of the literature and the inclusion of more studies than previous systematic reviews on this subject. Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the retrospective nature of the included studies introduces inherent risk of bias. Although risk of bias was assessed systematically, many studies demonstrated moderate to serious concerns, particularly in areas of confounding and outcome measurement. Additionally, the absence of granular data limited the ability to perform subgroup analyses based on key demographic or clinical variables such as age, sex, or comorbidities.

Second, relevant intraoperative variables - such as surgical time, blood loss, subscapularis management, and hospital stay - were inconsistently reported, precluding their inclusion in the analysis. Cost-effectiveness, another important consideration in surgical decision-making, was also not evaluated in the included literature.

Third, baseline differences in glenoid morphology were observed between groups, with the RTSA group exhibiting more complex configurations. This factor could influence both surgical technique and postoperative outcomes and represents a potential confounder that could not be adjusted for in the pooled analysis.

Lastly, the relatively short mean follow-up duration limits the ability to draw conclusions about long-term implant survival or functional outcomes. Longer-term studies are needed to determine whether the trends observed in this analysis persist over time.

Despite its limitations, this meta-analysis provides robust comparative evidence suggesting that RTSA may offer certain short-term advantages over TSA in the treatment of primary GHOA with an intact rotator cuff. These include lower complication and reoperation rates and improved outcomes on select PROMs. However, the choice between RTSA and TSA should remain individualized, taking into account patient-specific factors such as age, activity level, anatomical considerations, and surgical goals. Further high-quality, prospective research with long-term follow-up is essential to validate these findings and guide clinical decision-making.

| 1. | Daher M, Boufadel P, Lopez R, Chalhoub R, Fares MY, Abboud JA. Beyond the joint: Exploring the interplay between mental health and shoulder arthroplasty outcomes. J Orthop. 2024;52:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Daher M, Fares MY, Koa J, Singh J, Abboud J. Bilateral reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus bilateral anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2024;27:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dragonas CG, Mamarelis G, Dott C, Waseem S, Bajracharya A, Leivadiotou D. Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Versus Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients Aged Over 70 Without a Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tear: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Shoulder Elb Arthroplast. 2023;7:24715492231206685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jensen AR, Tangtiphaiboontana J, Marigi E, Mallett KE, Sperling JW, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis is associated with excellent outcomes and low revision rates in the elderly. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:S131-S139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flurin PH, Tams C, Simovitch RW, Knudsen C, Roche C, Wright TW, Zuckerman J, Schoch BS. Comparison of survivorship and performance of a platform shoulder system in anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. JSES Int. 2020;4:923-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Levy DM, Abrams GD, Harris JD, Bach BR Jr, Nicholson GP, Romeo AA. Rotator cuff tears after total shoulder arthroplasty in primary osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2016;10:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Piper C, Neviaser A. Survivorship of Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:457-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Young AA, Walch G, Pape G, Gohlke F, Favard L. Secondary rotator cuff dysfunction following total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study with more than five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:685-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim H, Kim CH, Kim M, Lee W, Jeon IH, Lee KW, Koh KH. Is reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) more advantageous than anatomic TSA (aTSA) for osteoarthritis with intact cuff tendon? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2022;23:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nazzal EM, Reddy RP, Como M, Rai A, Greiner JJ, Fox MA, Lin A. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty with preservation of the rotator cuff for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis has similar outcomes to anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for cuff arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:S60-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Orvets ND, Chan PH, Taylor JM, Prentice HA, Navarro RA, Garcia IA. Similar rates of revision surgery following primary anatomic compared with reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged 70 years or older with glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a cohort study of 3791 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32:1893-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51223] [Article Influence: 10244.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7683] [Cited by in RCA: 12507] [Article Influence: 1250.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Ardebol J, Flores A, Kiliç AĪ, Pak T, Menendez ME, Denard PJ. Patients 75 years or older with primary glenohumeral arthritis and an intact rotator cuff show similar clinical improvement after reverse or anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33:1254-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Haritinian EG, Belgaid V, Lino T, Nové-Josserand L. Reverse versus anatomical shoulder arthroplasty in patients with intact rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2020;44:2395-2405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hones KM, Hao KA, Trammell AP, Wright JO, Wright TW, Vasilopoulos T, Schoch BS, King JJ. Clinical outcomes of anatomic vs. reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in primary osteoarthritis with preoperative external rotation weakness and an intact rotator cuff: a case-control study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33:e185-e197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim SH. Comparison between Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for Older Adults with Osteoarthritis without Rotator Cuff Tears. Clin Orthop Surg. 2024;16:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kirsch JM, Puzzitiello RN, Swanson D, Le K, Hart PA, Churchill R, Elhassan B, Warner JJP, Jawa A. Outcomes After Anatomic and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for the Treatment of Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:1362-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mahylis JM, Friedman RJ, Elwell J, Kasto J, Roche C, Muh SJ. Anatomic vs. reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with glenoid retroversion of at least 15 degrees in rotator cuff intact patients: a comparison of short-term results. Semin Arthroplasty: JSES. 2024;34:130-139. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Merolla G, De Cupis M, Walch G, De Cupis V, Fabbri E, Franceschi F, Ascani C, Paladini P, Porcellini G. Pre-operative factors affecting the indications for anatomical and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in primary osteoarthritis and outcome comparison in patients aged seventy years and older. Int Orthop. 2020;44:1131-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Polisetty TS, Colley R, Levy JC. Value Analysis of Anatomic and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis with an Intact Rotator Cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103:913-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Steen BM, Cabezas AF, Santoni BG, Hussey MM, Cusick MC, Kumar AG, Frankle MA. Outcome and value of reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a matched cohort. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1433-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Trammell AP, Hao KA, Hones KM, Wright JO, Wright TW, Vasilopoulos T, Schoch BS, King JJ. Clinical outcomes of anatomical versus reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis, an intact rotator cuff, and limited forward elevation. Bone Joint J. 2023;105-B:1303-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Turnbull LM, Hao KA, Bindi VE, Wright JO, Wright TW, Farmer KW, Vasilopoulos T, Struk AM, Schoch BS, King JJ. Anatomic versus reverse total shoulder arthroplasty outcomes after prior contralateral anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with bilateral primary osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2024;48:801-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wright MA, Keener JD, Chamberlain AM. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes After Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty and Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients 70 Years and Older With Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis and an Intact Rotator Cuff. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e222-e229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Valsamis EM, Prats-Uribe A, Koblbauer I, Cole S, Sayers A, Whitehouse MR, Coward G, Collins GS, Pinedo-Villanueva R, Prieto-Alhambra D, Rees JL. Reverse total shoulder replacement versus anatomical total shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis: population based cohort study using data from the National Joint Registry and Hospital Episode Statistics for England. BMJ. 2024;385:e077939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/