Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.114166

Revised: September 27, 2025

Accepted: October 28, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 95 Days and 7.8 Hours

The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) is the most commonly injured ligament in ankle sprains. While most individuals recover with conservative management, some patients develop persistent pain and instability from chronic ATFL tears. Surgical repair is often required, and minimally invasive techniques are gaining popularity.

To evaluate the clinical outcomes of a novel, totally percutaneous (TP) modified Broström repair (MBR) for chronic ATFL insufficiency in a cohort of patients who failed conservative treatment.

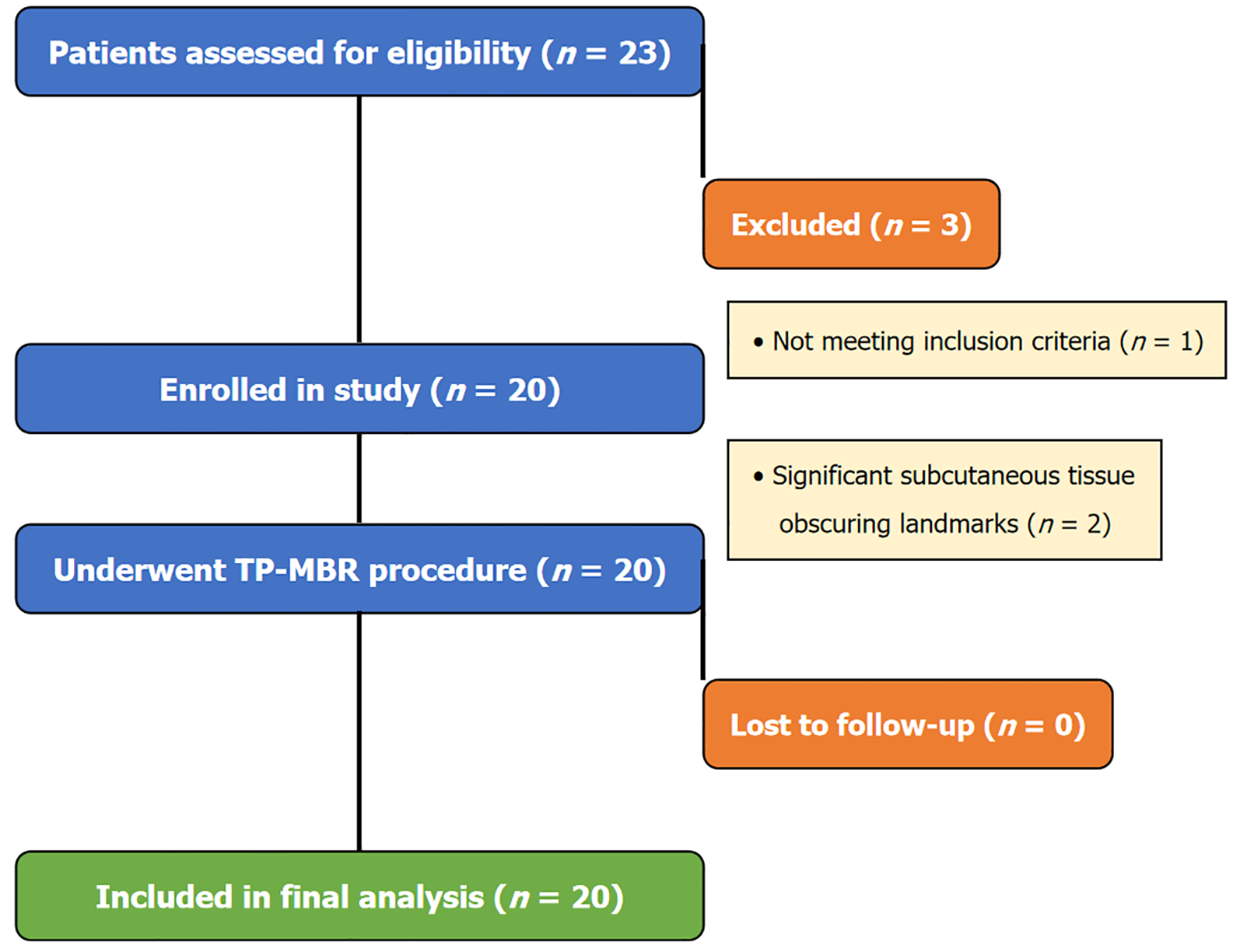

This retrospective study analyzed 20 patients (14 males, 6 females; mean age, 28.7 years) who underwent TP-MBR between 2023 and 2024 at a tertiary trauma center. All patients had persistent pain and instability for at least 3 months despite conservative treatment. Diagnosis was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging, arthroscopy, and stress testing. TP-MBR was performed using suture anchors and percutaneous ligament advancement. Functional outcomes were assessed using American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society score and Karlsson score at a mean follow-up of 1.5 years.

All procedures were completed successfully with no intraoperative complications. At a mean follow-up of 1.5 years, patients showed significant improvements in American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society score (from 39.85 to 84.4; P < 0.001) and Karlsson scores (from 43.8 to 87.4; P < 0.001). All patients returned to pre-injury activity levels with resolution of instability. The technique resulted in minimal tissue trauma, reduced operative time, accelerated recovery, and excellent cosmetic outcomes. No recurrences or major complications occurred.

TP-MBR is a safe and effective alternative to open Broström repair for chronic ATFL tears. It offers the benefits of a minimally invasive approach, including less trauma and faster rehabilitation, making it a valuable option for appropriately selected patients.

Core Tip: The totally percutaneous modified Broström repair preceded by diagnostic ankle arthroscopy and confirmed by intraoperative stress views, offers a safe and effective minimally invasive alternative for chronic anterior talofibular ligament tears unresponsive to at least 3 months of conservative management. This technique minimizes soft tissue trauma, reduces operative time, and promotes faster recovery with excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes, making it particularly beneficial for active patients aiming for a quicker return to sports and daily activities. This case series demonstrates significant improvement in functional scores and resolution of instability at 18-month follow-up, highlighting its potential as a preferred surgical option.

- Citation: Elalfy MM, Embaby OM, Mekkawy MM, Sayed AA, Abushal MH. Percutaneous anterior talofibular ligament repair: A new technique for chronic ankle instability. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 114166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/114166.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.114166

The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) is the most frequently injured ligament in the ankle, often resulting from inversion sprains. While conservative management, including rest, physiotherapy, and bracing, is effective for the majority of acute ATFL injuries, a significant subset of patients develops chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI) due to persistent pain and functional deficits[1].

CLAI can severely impact an individual’s quality of life, limiting participation in sports and daily activities. Current guidelines recommend a trial of conservative management for at least 6 months before considering surgical intervention for chronic ATFL instability[2]. Traditional surgical interventions for CLAI, such as the modified Broström repair (MBR), have historically involved open or mini-open approaches. These techniques aim to restore ankle stability by directly repairing or reconstructing the damaged ATFL and reinforcing the lateral ankle structures, often with augmentation of the inferior extensor retinaculum[3].

While open MBR has demonstrated reliable long-term outcomes, it is associated with potential drawbacks, including larger incisions, increased soft tissue dissection, and a longer rehabilitation period[4]. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in minimally invasive techniques for ATFL repair, driven by the desire to reduce surgical morbidity, accelerate recovery, and improve cosmetic outcomes. Arthroscopic and percutaneous approaches have emerged as promising alternatives, offering direct visualization of intra-articular pathology and minimizing disruption to surrou

In contrast, totally percutaneous (TP) modified Broström repair (MBR) reduces equipment dependency, offering a simpler and more accessible alternative, particularly in centers with limited arthroscopic resources. This study fills a gap in the literature by presenting a percutaneous option that does not rely on continuous arthroscopic assistance during the repair itself, making it a viable option in a wider range of clinical settings.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Red Crescent Hospital (Mansoura, Egypt) and included 20 patients who underwent TP-MBR for chronic symptomatic ATFL tears between January 2023 and January 2024. All patients presented with persistent lateral ankle pain and mechanical instability after at least 3 months of supervised conservative treatment. All procedures were performed by a single experienced foot and ankle consultant to ensure technical consistency.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Age between 20 years and 45 years; (2) Persistent pain or mechanical instability after at least 3 months of supervised non-operative care; a magnetic resonance imaging-confirmed isolated ATFL tear; (3) Positive pre-operative anterior drawer and talar tilt tests; and (4) An arthroscopically confirmed isolated ATFL tear without additional ligamentous or osteochondral pathology.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Multiligamentous ankle injuries (e.g., calcaneofibular ligament, deltoid ligament invo

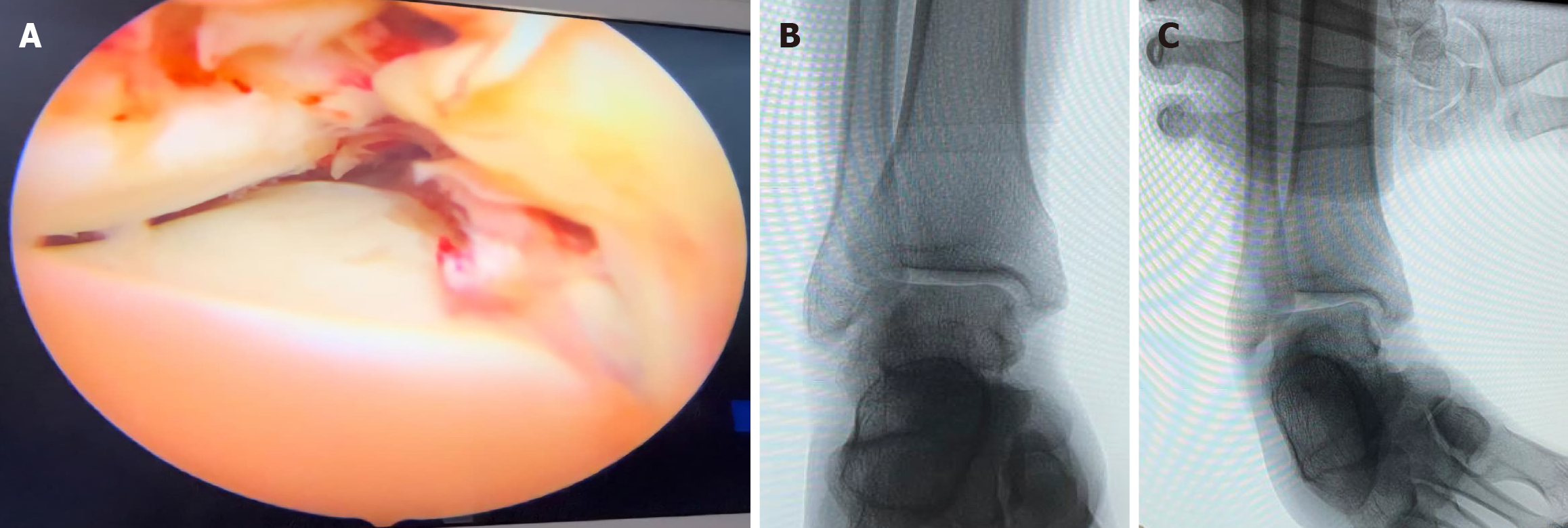

Clinical examination revealed positive anterior drawer and talar tilt tests in all patients, indicative of ATFL insufficiency. Diagnosis was confirmed via magnetic resonance imaging, followed by diagnostic ankle arthroscopy and intraoperative stress varus view by C-arm to confirm isolated ATFL tear without associated intra-articular pathology (Figure 2).

All surgical procedures were performed under regional anesthesia with the patient in a supine position. A diagnostic ankle arthroscopy was initially performed through standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals to confirm the isolated ATFL tear and rule out any associated intra-articular pathologies. This was followed by an intraoperative stress varus view under C-arm guidance to further confirm instability before proceeding with the repair. The TP-MBR was then initiated. Each step is detailed below.

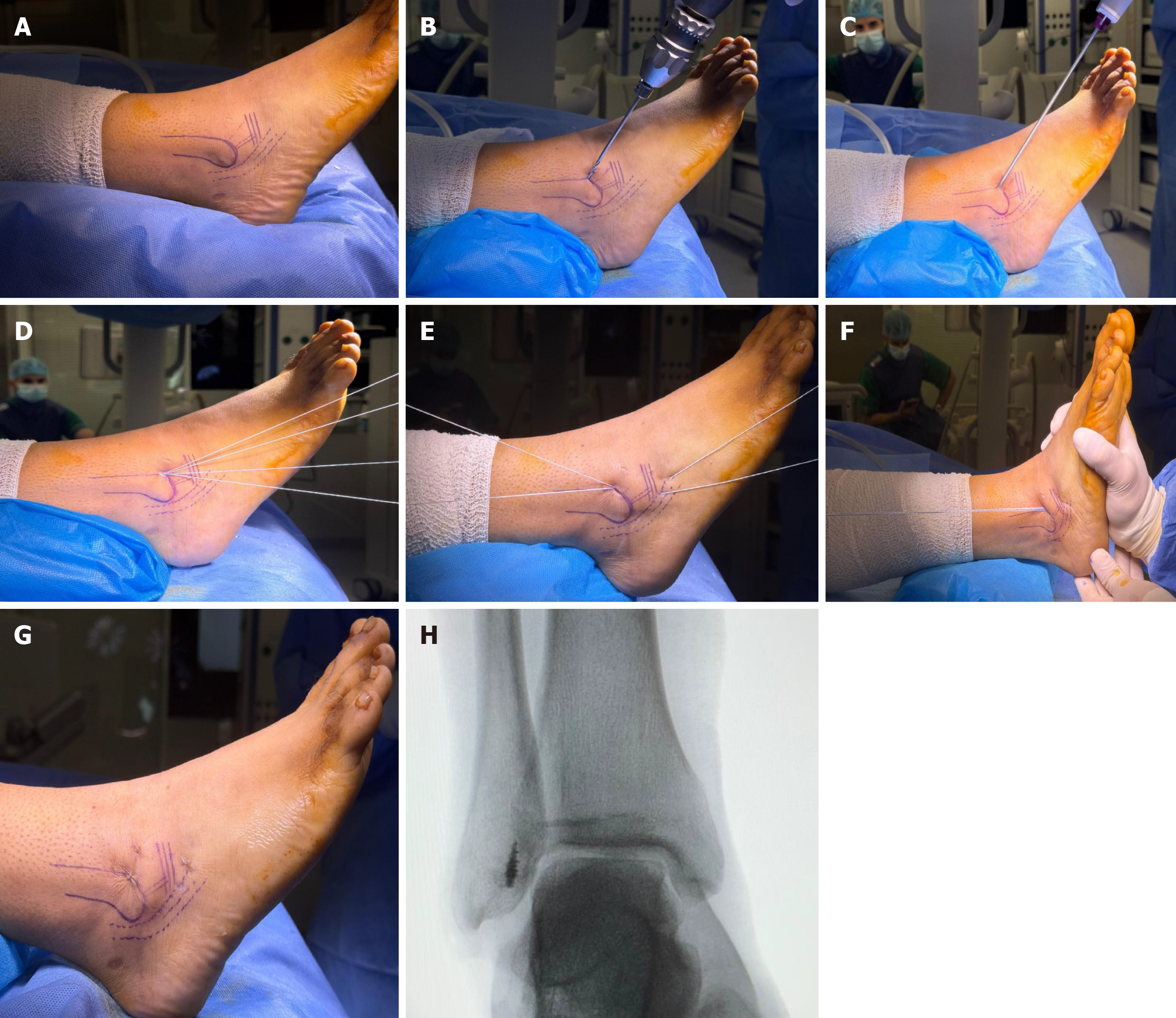

Step 1: Identification of anatomical landmarks and initial incision: The anatomical landmarks are meticulously identified and palpated. These include the distal end of the fibula with the peroneal tendons coursing posteriorly. The precise direction and course of the ATFL are delineated, along with the orientation of the inferior extensor retinaculum. These landmarks are crucial for accurate placement of instruments and implants (Figure 3A).

Step 2: Pilot hole creation and suture anchor insertion: Following the identification of anatomical landmarks and the creation of a small stab incision, a drill guide is carefully positioned over the distal fibula at the anatomical origin of the ATFL. A pilot hole is then created at an approximate angle of 20° to 45° posteriorly directed relative to the fibular shaft. This angle corresponds precisely to the ATFL footprint, ensuring optimal anchor placement for anatomical repair. A 3.5-mm suture anchor is then inserted into this pilot hole with the ankle held in plantarflexion. Final placement of the anchor is confirmed by direct visualization through the arthroscopic portals. Once properly seated, four suture threads are retrieved from the anchor (Figure 3B-D).

Step 3: Suture passage and retinaculum reinforcement: Each suture thread is passed subcutaneously towards the talar insertion of the ATFL. Subsequently, these sutures are passed through the inferior extensor retinaculum. The sutures are then meticulously arranged in pairs to facilitate secure anatomical reconstruction and reinforcement of the ligament. To create a robust reinforcement loop, the sutures are redirected through the same exit point, passed once more through the inferior extensor retinaculum, and then guided back to the original anchor entry site in the fibula. This technique effectively secures both the ATFL footprint on the talus and incorporates the extensor retinaculum in an anatomical position, providing additional stability before final knot tying (Figure 3E).

Step 4: Suture tying and soft tissue release: The anchor sutures are tied with the foot held in a neutral position. This neutral position is critical to restore the native tension of the ATFL, ensuring appropriate ligamentous stability. After tying the sutures with the appropriate tension, any interposed subcutaneous or soft-tissue strands that might obstruct the suture pathway are carefully identified and released. This is typically performed using small artery forceps to ensure unobstructed fixation and prevent soft-tissue entrapment (Figure 3F and G). Optimal stability was then confirmed by performing a varus stress test after anchor placement, demonstrating excellent ankle stability and successful fixation of the ligament (Figure 3H).

Postoperatively, patients were immobilized in a slab for 2 weeks, followed by a walking boot for an additional 2 weeks. Thereafter, a structured rehabilitation program was initiated, emphasizing early range of motion, gradual progression of weight-bearing, and strengthening exercises over the subsequent month. Return to sports and unrestricted activity was individualized and determined based on clinical recovery and achievement of functional milestones, as detailed in Table 1.

| Timeframe | Protocol |

| Weeks 0-2 | Immobilization in a non-weight-bearing posterior slab; focus on elevation and ice to control swelling |

| Weeks 2-4 | Transition to a walking boot; partial weight-bearing as tolerated; gentle passive and active range of motion exercises (dorsiflexion, plantarflexion) |

| Weeks 4-8 | Wean off walking boot and transition to an ankle brace; full weight-bearing as tolerated; begin proprioceptive and neuromuscular training (e.g., single-leg stance); start gentle strengthening exercises (e.g., resistance bands for eversion and inversion) |

| Months 2-4 | Discontinue brace for daily activities; progress strengthening exercises; introduce sport-specific drills and activities |

| More than 4 months | Gradual return to unrestricted sports and activities based on clinical assessment and functional milestones |

All continuous outcome variables, including American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society score and Karlsson score, were reported as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The paired t-test was used to compare preoperative and postoperative functional scores. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0 (IBM SPSS, Turkey).

This study included 20 patients (14 males, 6 females) with a mean age of 28.7 ± 5.4 years. The mean follow-up period was 1.5 years. All surgical procedures were completed without intraoperative complications.

Post-operatively, patients demonstrated significant and consistent improvements in functional outcomes. The mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society score substantially increased from a pre-operative mean of 39.85 ± 4.2 to 84.4 ± 3.1 at 1.5 years post-operatively (P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval for improvement: 37.8-43.1). The mean Karlsson score also showed significant improvement from 43.8 ± 5.1 pre-operatively to 87.4 ± 4.5 at final follow-up (P < 0.001).

Among the cohort, one patient (5%) experienced localized post-operative redness and swelling, which fully resolved within 1 month following a structured physiotherapy and rehabilitation program. Another patient (5%) reported persistent mild ankle pain during prolonged weight-bearing activities, without associated instability. No recurrences of instability or wound-related complications were observed throughout the 1.5-year follow-up period.

In this study, we found that the TP-MBR is a safe and effective surgical option for patients with chronic ATFL tears. Our results showed significant improvement in functional scores and a high rate of return to pre-injury activity levels, comparable to those reported for both traditional open Broström procedures and other minimally invasive techniques[7,8].

One of the primary advantages of our percutaneous approach is the minimal soft tissue disruption, which is particularly beneficial for patients with a lean body habitus and clearly palpable anatomical landmarks[9,10]. This less invasive method preserves the integrity of surrounding tissues, leading to reduced post-operative pain, swelling, and scarring, and facilitates a faster recovery[11]. Furthermore, the TP-MBR technique is less dependent on advanced arthroscopic equipment, making it a more accessible option in resource-limited settings. The potential cost-effectiveness of this approach compared to fully arthroscopic procedures is an additional benefit that warrants further investigation.

The inclusion of diagnostic ankle arthroscopy prior to repair is a crucial step that allows for the identification and treatment of concomitant intra-articular pathologies, thereby optimizing surgical outcomes[12]. Regarding postoperative rehabilitation, our protocol, which involves initial immobilization in a slab for 2 weeks followed by a walking boot for an additional 2 weeks, represents a moderately accelerated approach. This contrasts with some traditional open Broström repair protocols that advocate for longer non-weight-bearing periods, typically 4-6 weeks. However, some studies on modified Broström repairs, even open ones, have demonstrated successful outcomes with immediate protected full weight-bearing from post-operative day 1[7]. With minimal soft tissue disruption, our percutaneous technique allows for a rehabilitation timeline more comparable to accelerated protocols often seen with arthroscopic or augmented repairs, potentially offering an advantage over traditional open methods in terms of patient recovery and return to function. In contrast, some protocols remain more conservative, recommending immobilization in a cast for 2 weeks followed by bracing, with partial weight-bearing initiated around 4 weeks and resistance training delayed until 6 weeks postoperatively[8]. Our protocol’s emphasis on early range of motion and progressive strengthening is consistent with contemporary rehabilitation principles aimed at optimizing functional outcomes and preventing stiffness, as highlighted in recent guidelines for ankle ligament repair[13].

This study has several limitations. The retrospective design, small sample size, and single-center setting limit the generalizability of our findings. The 1.5-year follow-up period is relatively short, and longer-term studies are needed to assess the durability of the repair. We also acknowledge that two potential candidates were excluded due to significant subcutaneous tissue obscuring landmarks, and one case was converted to an open procedure intraoperatively due to excessive swelling and hematoma, highlighting the importance of careful patient selection. Future prospective, multi-center studies with larger cohorts and comparative groups are needed to further validate the efficacy of this technique.

Studies on traditional open Broström procedures have demonstrated excellent long-term outcomes, with some reporting success rates extending beyond two decades[14]. For minimally invasive and arthroscopic techniques, emerging evidence suggests comparable clinical outcomes to open repairs, often with reduced wound-related complications[15,16]. However, specific long-term data for purely percutaneous techniques, especially those without arthroscopic assistance, remain limited. Potential complications associated with both open and minimally invasive approaches include nerve injury (particularly the superficial peroneal nerve), stiffness, persistent pain, and re-instability[17]. Our percutaneous approach, by minimizing dissection, theoretically reduces the risk of extensive soft tissue damage and associated complications, but careful attention to anatomical landmarks is paramount to avoid iatrogenic nerve injury.

This case series demonstrates that when performed after comprehensive diagnostic confirmation, TP-MBR is a safe and effective surgical intervention for chronic ATFL tears that have failed conservative management. The minimally invasive nature of this technique offers several advantages over traditional open methods, including reduced soft tissue trauma, minimal scarring, and potentially faster rehabilitation. Our findings indicate significant improvements in functional outcomes and resolution of mechanical instability at a mean follow-up of 1.5 years. This novel approach represents a valuable alternative for active patients seeking a quicker return to sports and daily activities while upholding the fundamental biomechanical principles of the Broström procedure. Further research with larger cohorts and longer follow-up periods, ideally in comparative studies, will help to solidify the long-term benefits and broader applicability of this promising technique.

The authors thank the surgical and nursing teams who assisted with patient care.

| 1. | Vulcano E, Marciano GF, Pozzessere E. Clinical Outcomes of a Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Brostrom Technique without Arthroscopic Assistance. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14:2252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhao B, Sun Q, Xu X, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Gao Y, Zhou J. Comparison of arthroscopic and open Brostrom-Gould surgery for chronic ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guyonnet C, Vieira TD, Wackenheim FL, Lopes R. Arthroscopic Modified Broström Repair with Suture-Tape Augmentation of the Calcaneofibular Ligament for Lateral Ankle Instability. Arthrosc Tech. 2024;13:102887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu Z, Lu H, Yuan Y, Fu Z, Xu H. Mid-term follow-up evaluation of a new arthroscopic Broström procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang G, Li W, Yao H, Tan R, Li C. The precision of technical aspects in the minimally invasive Broström-Gould procedure: a cadaveric anatomical study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2024;19:450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang Y, Zhao M, Yuan C, Du X, Long X, Xu J. Arthroscopic Repair of Anterior Talofibular Ligament After Distal Fibular Nonunion Excision Using a 2-Portal, No-Ankle-Distraction Technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2025;14:103703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Petrera M, Dwyer T, Theodoropoulos JS, Ogilvie-Harris DJ. Short- to Medium-term Outcomes After a Modified Broström Repair for Lateral Ankle Instability With Immediate Postoperative Weightbearing. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1542-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhou YF, Zhang ZZ, Zhang HZ, Li WP, Shen HY, Song B. All-Inside Arthroscopic Modified Broström Technique to Repair Anterior Talofibular Ligament Provides a Similar Outcome Compared With Open Broström-Gould Procedure. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:268-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xie X, Chen L, Fan C, Song S, Yu Y, Jiao C, Pi Y. The lowest point of fibula (LPF) could be used as a reliable bony landmark for arthroscopic anchor placement of lateral ankle ligaments ----compared with open Broström procedure. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hunt KJ, Rodriguez-fontan F. Lateral Ankle Instability: Arthroscopic Broström and Minimally Invasive Techniques. In: D’Hooghe P, Hunt KJ, McCormick JJ, editors. Ligamentous Injuries of the Foot and Ankle. Cham: Springer, 2022: 97-104. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Lee YK, Lee HS, Cho WJ, Won SH, Kim CH, Kim HK, Ryu A, Kim WJ. Peroneal tendon irritation after arthroscopic modified Broström procedure: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e18424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pellegrini MJ, Sevillano J, Ortiz C, Giza E, Carcuro G. Knotless Modified Arthroscopic-Broström Technique for Ankle Instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:475-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu Y, Cao YX, Li XC, Xu XY. Revision lateral ankle ligament reconstruction for patients with a failed modified Brostrom procedure. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2022;30:10225536221125948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moorthy V, Sayampanathan AA, Yeo NEM, Tay KS. Clinical Outcomes of Open Versus Arthroscopic Broström Procedure for Lateral Ankle Instability: A Meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2021;60:577-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wittig U, Hohenberger G, Ornig M, Schuh R, Leithner A, Holweg P. All-arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament is comparable to open reconstruction: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2022;7:3-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Brostrom Procedure Clinical Practice Guideline. [cited 15 Augst 2025]. Available from: https://medicine.osu.edu/-/media/files/wexnermedical/patient-care/healthcare-services/sports-medicine/education/medical-professionals/knee-ankle-and-foot/brostrom-cpg2020.pdf?la=en&hash=26BA5DF208EC168E471DA8D84218B56CD4717B85. |

| 17. | Alhaddad A, Gronfula AG, Alsharif TH, Khawjah A, Al Shareef NS, AlThagafi AA, Sarraj TS, Alnajrani A. A Comparative Analysis of Complication Rates in Arthroscopic Repair of the Lateral Ankle Ligament and the Brostrom-Gould Technique: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e48460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/