Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110324

Revised: June 15, 2025

Accepted: October 20, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 196 Days and 13.8 Hours

Recovering from anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction can be chal

To explore whether combining ESWT with standard postoperative rehabilitation truly leads to better recovery compared with rehab alone.

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, evaluating participant status following ACL reconstruction with standard rehabilitation and without augmented ESWT. This meta-analysis included six studies (five randomized controlled trials, one non-randomized clinical study). The outcome measures were the Lysholm score, International Knee Docu

ESWT modestly improved Lysholm scores (weighted mean difference: 3.72; 95% confidence interval: -0.27 to 7.71) with high heterogeneity (I2: 96%, P < 0.001) when compared with standard rehabilitation. Focused ESWT showed greater benefits compared with radial ESWT. No significant differences were found in the International Knee Documentation Committee scores, visual analog score, or KT-1000 measurements. Substantial variability and publication bias were noted.

ESWT improved Lysholm scores but did not show other significant benefits. Due to the limited evidence, further standardized, placebo-controlled trials are needed to confirm its effectiveness in ACL reconstruction.

Core Tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the functional benefits of the addition of extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) to postoperative rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. While some studies showed promising improvements, especially with focused ESWT, overall evidence remains mixed due to variations in technique, study design, and follow-up duration. Our findings suggest that ESWT may support recovery; however, more rigorous, standardized trials are needed to confirm its actual clinical value.

- Citation: Salimi M, Keshtkar A, Mosalamiaghili S, Lowe W, Ahmad A, Sharafatvaziri A. Evaluating the efficacy of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in postoperative rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2025; 16(12): 110324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i12/110324.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i12.110324

Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) constitutes one of the most commonly performed surgical operations intended to restore stability and function to the knee joint after the initial injury[1]. Notwithstanding the success of the operation, optimizing rehabilitation after the surgery to obtain the best results is an ever-present challenge[1]. Rehabilitation activities after surgery have always been directed towards maximal improvement of joint movements, muscle power, and overall functionality. In recent years, however, there have been some suggestions that extrinsic therapeutic measures such as extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) can aid in recovery while shortening the rehabilitation period[2].

ESWT is a noninvasive treatment that delivers shock waves to body parts affected by chronic pain and other conditions, such as tendonitis[2]. It was initially used to break kidney stones[3]. This therapy is believed to stimulate tissue repair, decrease inflammation, and enhance the material bonding of the grafts used during the ACL reconstruction (ACLR)[4]. Therefore, understanding the effectiveness of this therapy as it is increasingly being embraced in musculoskeletal rehabilitation, particularly in the recovery of ACLR, is essential[5].

Although ESWT techniques appear effective, their advantages over standard rehabilitation approaches remain to be clarified[6-8]. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effect of ESWT self-reported outcomes and function after surgical ACLR. The study aimed to fill this gap by determining whether ESWT approaches can offer clinically meaningful benefits over traditional rehabilitation approaches in patients’ overall recovery processes.

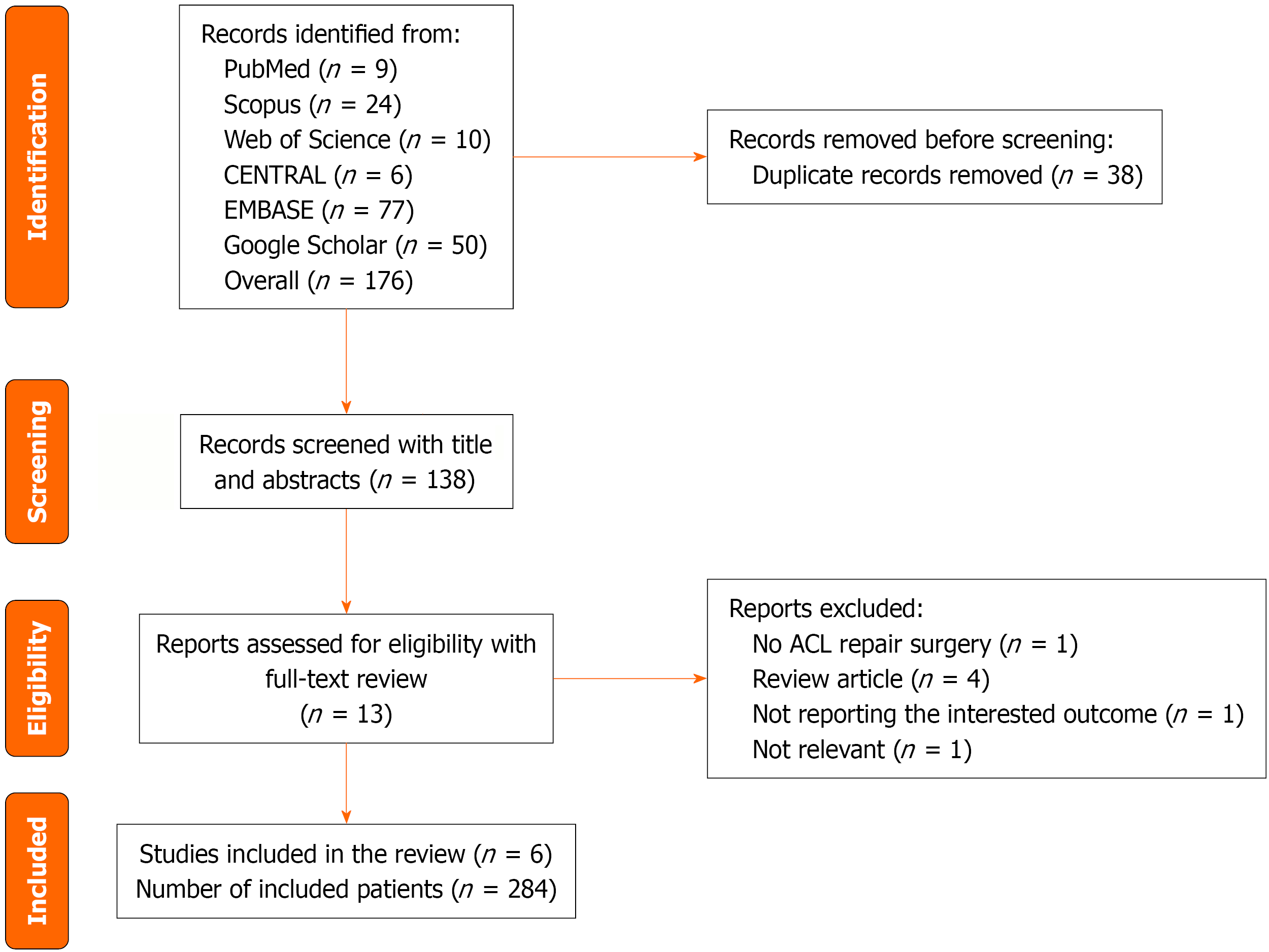

This study follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (also known as PRISMA) protocol for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses[9] (Figure 1). The protocol of this study was registered in the open science framework[10].

To compile relevant studies a systematic search was conducted in five databases, including the Cochrane Central Registry of Clinical Trials, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and EMBASE from January 1, 1990 to August 1, 2024. The MESH terms used for this search were “Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy”, “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction”, and “Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Grafting”. A detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Randomized and non-randomized control trials and observational studies (cohort and cross-sectional); and (2) Studies that enrolled patients with ACL repair surgery regardless of the method of surgery and ESWT used as the rehabilitation after surgery as the comparator group that received the routine rehabilitation techniques.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Preprint studies; (2) Systematic review and meta-analysis studies; and (3) Studies without any comparator group.

Two authors (Keshtkar A, Mosalamiaghili S) independently reviewed the citations found in the search results to determine which studies were appropriate for inclusion in our systematic review. In addition, the same authors retrieved data using the data extraction form. Any discrepancies between the screening and data extraction results were handled by consulting the senior author (Salimi M). The primary data extraction form included the title of the included study, first author name, year of publication, type of study, enrolled patients, intervention, comparison group, and follow-up, preoperation and postintervention KT-1000 score, Lysholm score, visual analog score (VAS), International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), range of motion, and graft incorporation. Data extraction was cross-checked independently.

The quality of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, and most outcomes were rated as low to very low certainty due to high heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and potential publication bias.

The quality of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, and most outcomes were rated as low to very low certainty due to high heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and potential publication bias.

Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Risk of Bias Assessment 2 tool for clinical trials and the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Intervention. Results are available in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Two of the outcomes, range of motion and graft incorporation, were not reported in at least two studies, so meta-analysis could not be performed for those variables. To compare KT-1000, Lysholm score, IKDC, and VAS between the ESWT and control groups, we used a weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) as the effect size. To find the Lysholm score and IKDC mean standard deviation (SD) change, we used the following formulas:

Mean change: Mean follow-up - mean baseline.

SD change: Sqrt (SD follow-up2) + (SD baseline2) - (Correlation coefficient × SD follow-up × SD baseline).

Correlation coefficient: (SD follow-up2 + SD baseline2 - SD change2)/(2 × SD follow-up × SD baseline)[10].

If the SD change was not reported in any of the studies, the correlation coefficients were considered 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 for the analysis.

A subgroup analysis was done where possible according to the method of ESWT administration including radial ESWT applied all over the local area and focused ESWT, which focused the waves on the desired tissue depth. Because of the significant heterogeneity between the studies’ follow-up periods, heterogeneity between the studies was assessed with I2 statistics and Cochrane’s Q test[12]. Publication bias was calculated with Begg’s, Egger’s, and funnel plots[13]. All analyses were performed in STATA (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX, United States: StataCorp LLC.). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A total of 176 articles were included in the screening process; 38 were duplicate articles and removed from the primary screening process. Thirteen articles entered the full-text screening process, and six[4,6-8,14,15] articles, including five randomized controlled trials (RCT)[4,7,8,14,15] and one non-randomized clinical study (NRCS)[6], were included in the meta-analysis. The reason for the exclusion of each article that entered the full-text screening phase is reported in Supplementary Figure 1. Demographic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

| Ref. | Study design | Gender | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome | Follow-up |

| Li et al[4] 2022 | RCT | Male | ACLR | Radial ESWT following exercise training | Exercise training | Function and stability of knee joint | 6 months |

| Wang et al[8] 2014 | RCT | Male and female | Primary ACLR | Focused ESWT in a single session with 1500 impulses | No ESWT | IKDC, KT-1000, Lysholm, autograft ratios | 2 years |

| Rahim et al[6] 2022 | NRCS | Male | ACLR with single autograft hamstring reconstruction | Focused ESWT at 7 weeks, 8 weeks, and9 weeks postoperation and for 6 weeks in another group 7-12 weeks with 500 shocks | Physiotherapy | Lysholm, graft incorporation | 3 weeks, 6 weeks |

| Song et al[7] 2024 | RCT | Male and female | ACLR | Radial ESWT at the second postoperative day with 2500 impulses for 6 weeks | Sham ESWT + standard rehabilitation | Lysholm, ROM, IKDC, VAS | 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 24 weeks |

| Weninger et al[14] 2023 | RCT | Male and female | ACLR | Focused ESWT at 4 weeks, 5 weeks, and 6 weeks with 1500 impulses | No ESWT | VAS, Lysholm, IKDC, return to activity, tunnel liquid effusion | 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months |

| Zhang et al[15] 2022 | RCT | Male | ACLR | Radial ESWT for 5 weeks and 3 months postoperatively with 2000 impulses | Standard treatment | IKDC, Lysholm, Tegner, KT-1000, ACL graft signal/noise quotient | 3 months, 6 months, 24 months |

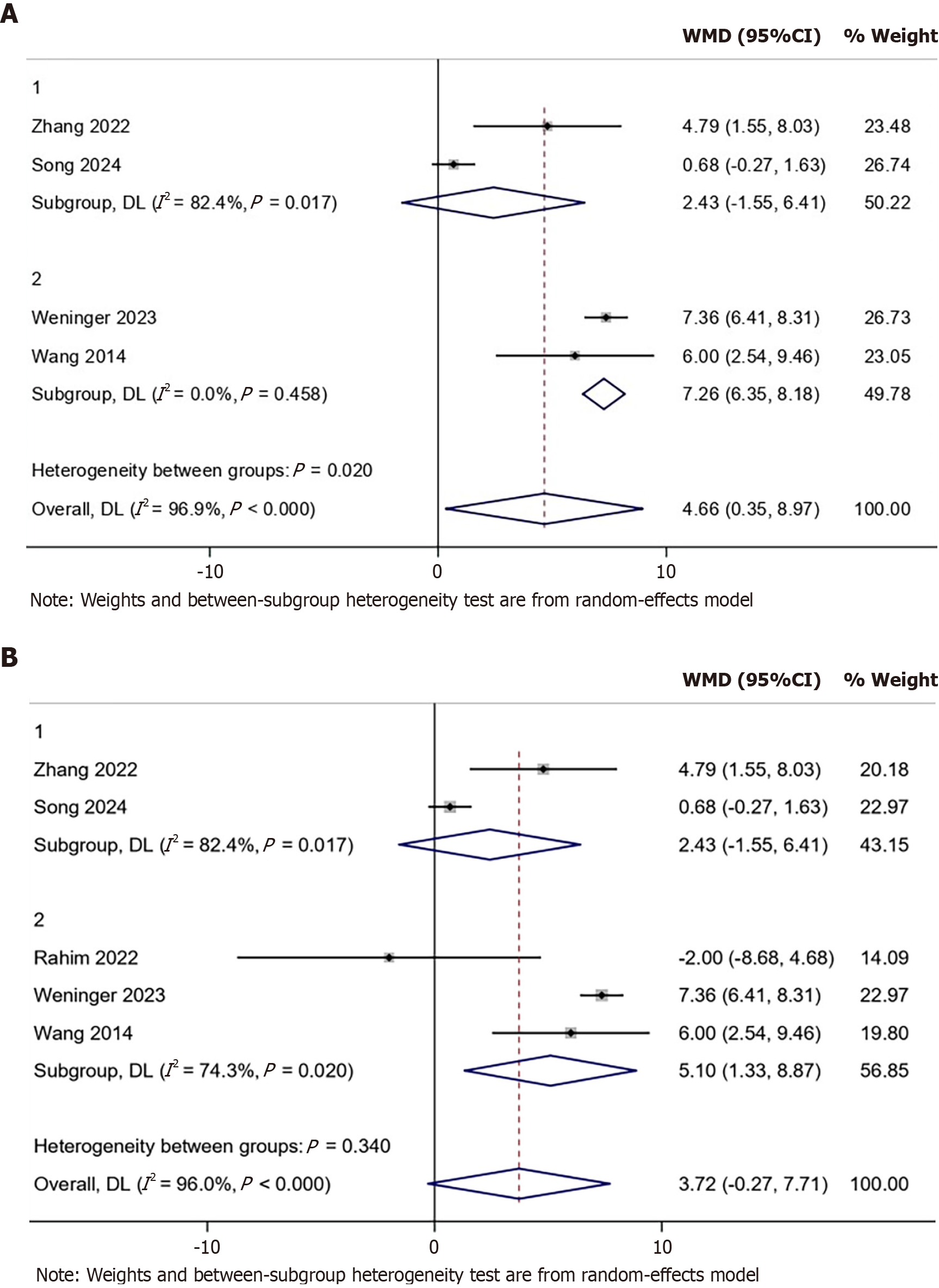

Five studies, including four RCTs[7,8,14,15] and one NRCS[6], reported the Lysholm score of their participants. Patients in the ESWT group did not have a higher Lysholm score compared with the control group when pooling all of the available studies (WMD: 3.72; 95%CI: -0.027 to 7.71) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 96%, P < 0.001). Moreover, subgroup analysis showed that the focused ESWT group had a higher Lysholm score (WMD: 5.10, 95%CI: 1.33-8.87), but no significant differences were found in radial ESWT and control groups (WMD: 2.43, 95%CI: -1.55 to 6.41). However, after excluding the NRCS study, the result of the RCTs showed a significantly higher Lysholm score for patients in the ESWT group (WMD: 7.26; 95%CI: 6.35-8.18) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 96.9%, P < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis showed that the focused ESWT group had higher scores than the control group (WMD: 7.26, 95%CI: 6.35-8.18). Funnel plot showed significant publication bias (Figure 2). Begg’s and Egger’s tests showed significant publication bias with P = 1.000 and 0.962, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). In addition to the subgroup analysis, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding the non-randomized study. This resulted in a significant WMD of 7.26 (95%CI: 6.35-8.18), suggesting that the inclusion of the NRCS data may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

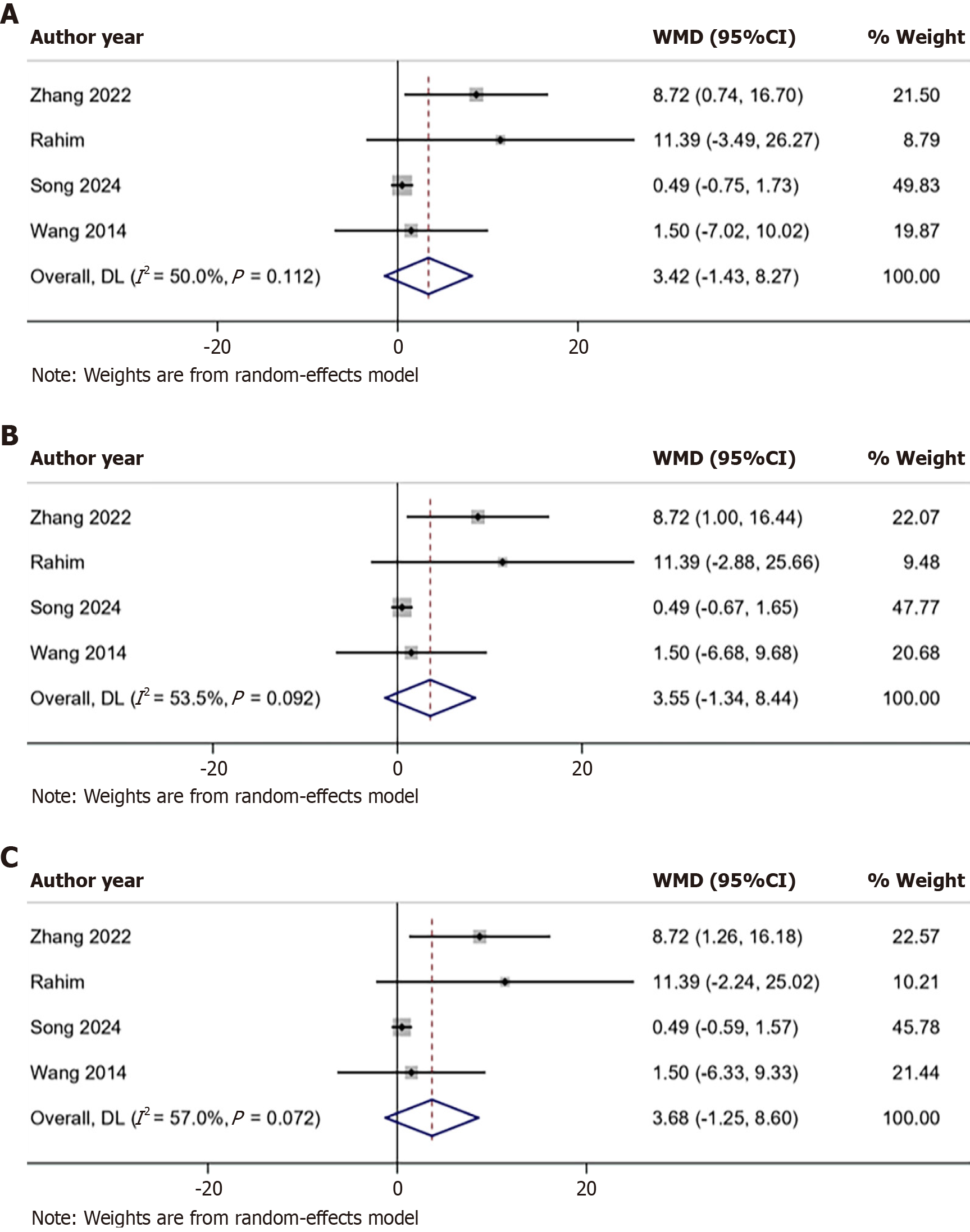

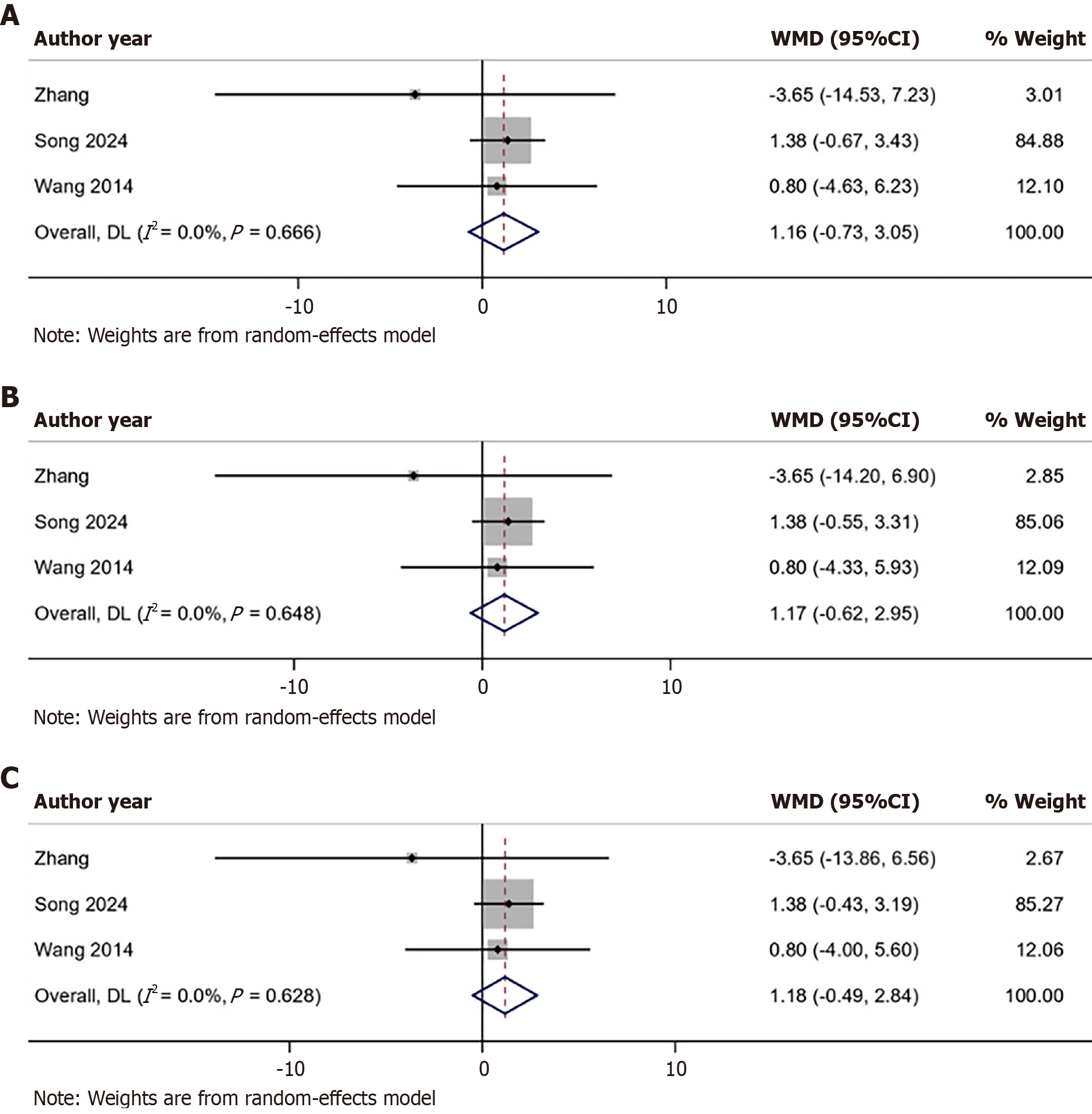

Four articles, including three RCTs[7,8,15] and one NRCS[6], reported the baseline Lysholm scores of their patients. Three meta-analyses were done because none of the studies reported the SD change. We considered R to calculate SD change as 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 in the first, second, and third analyses, respectively. Lysholm score did not significantly change in the ESWT group compared with the control group in any of the analyses (Figure 3).

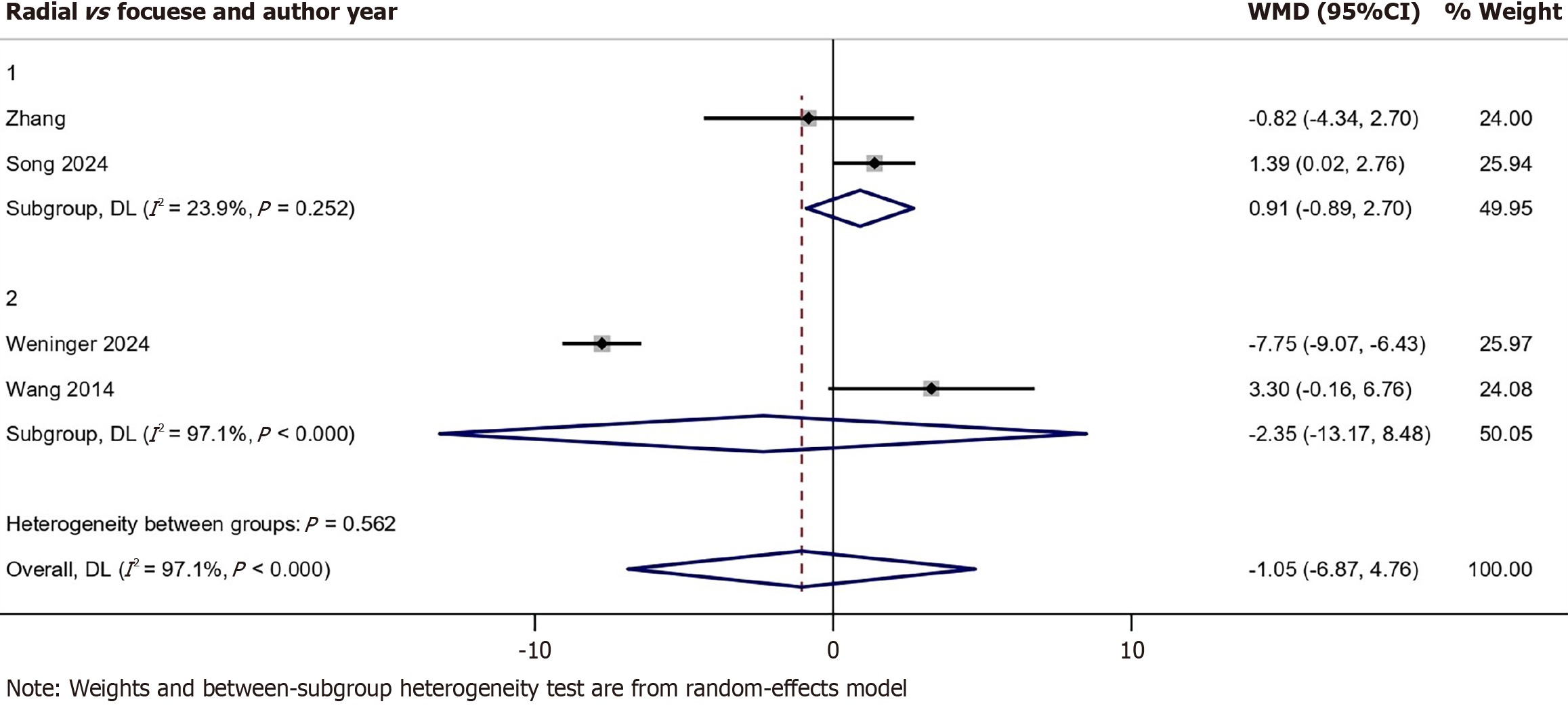

Four RCTs[7,8,14,15] reported the IKDC score. Patients in the ESWT group did not show significant differences between the two groups (WMD: -1.05, 95%CI: -6.87 to 4.76) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 97.1%, P < 0.001). Moreover, subgroup analysis did not show significant differences between radial ESWT and control groups (WMD: 0.91, 95%CI: -0.89 to 2.70) nor in the focused ESWT and control group (WMD: -2.35. 95%CI: -13.17 to 8.48) (Figure 4).

Three RCTs[7,8,15] were reported as the baseline IKDC of their patients. Three meta-analyses were done because none of the studies reported the SD change. We considered R to calculate the SD change as 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 in the first, second, and third analyses, respectively. IKDC score did not change significantly in the ESWT group in comparison with the control group in any of the analyses (Figure 5).

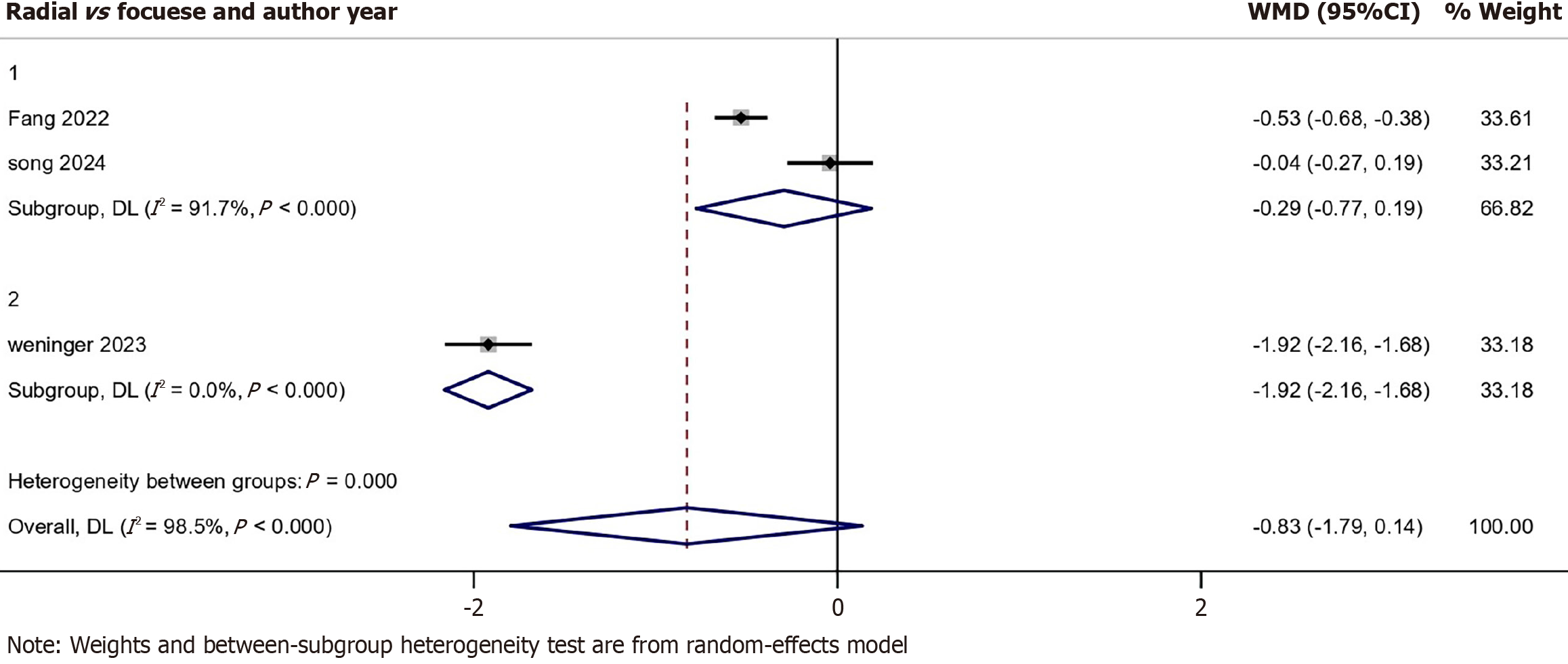

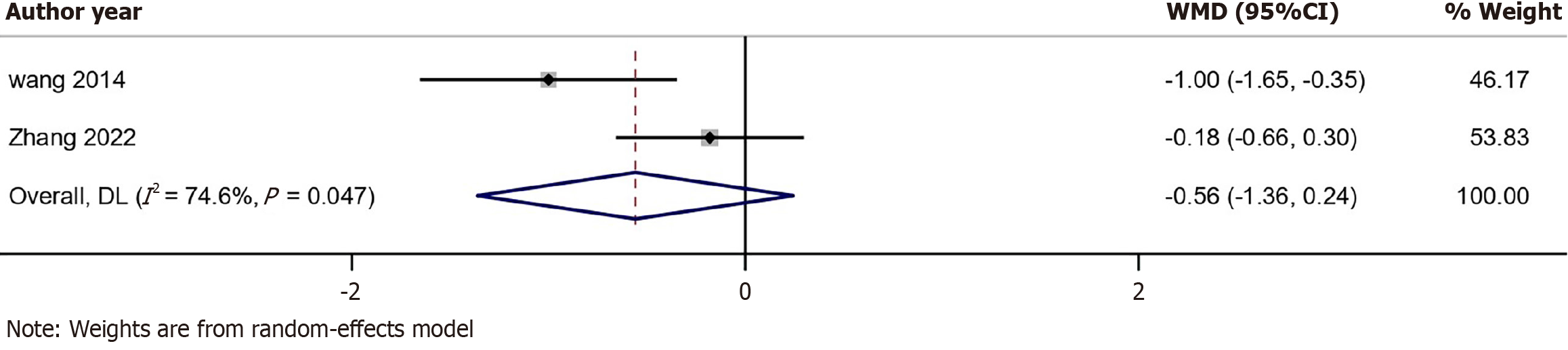

Three RCTs[4,7,14] reported the VAS. No significant differences were found between the ESWT group and the control group (WMD: -0.83, 95%CI: -1.79 to 0.14) and with substantial heterogeneity (I2: 98.5%, P < 0.001) (Figure 6). Two studies[8,15] reported the KT-1000. No significant differences were found between the ESWT group and the control group (WMD: -0.56, 95%CI: -1.36 to 0.24) and with substantial heterogeneity (I2: 74.6%, P = 0.047) (Figure 7).

The findings across the included studies revealed both significant and nonsignificant results regarding the efficacy of ESWT in postoperative rehabilitation following ACLR. Subgroup analyses indicated a more pronounced effect for focused ESWT compared with radial ESWT. Studies with longer follow-up durations consistently reported significant improvements in functional outcomes, such as Lysholm scores[8,14,15], whereas studies with shorter follow-ups often showed no significant differences between ESWT and control groups[4,6,7]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was widely used across the studies to evaluate graft maturation and tendon-bone integration, often measured through signal intensity ratios or signal-to-noise quotients. While ESWT showed promise in enhancing certain aspects of postoperative recovery, such as graft maturation and pain reduction, the clinical evidence remains inconsistent, with significant variability in outcomes depending on follow-up durations, ESWT modalities, and study designs.

While the meta-analysis by Shin et al[16] offered a helpful overview of how ESWT might support recovery after ACLR, our study takes a step further by breaking down the differences between focused and radial ESWT and by exploring how treatment timing and intensity might influence outcomes. We also ran sensitivity analyses to better understand the source of heterogeneity. In addition, we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE framework and presented the risk of bias visually, making our findings easier to interpret. Overall, we aimed to build on the existing literature by providing more practical insights that can help guide personalized rehabilitation strategies.

Although our study included only four RCTs, our subgroup and sensitivity analyses provided complementary insights into focused vs radial ESWT, highlighting modality-specific trends. Notably, none of the included RCTs used objective functional outcome measures such as balance assessments or proprioceptive evaluation, which are vital components in ACL rehabilitation. Future trials should incorporate these domains.

New studies[17,18] are valuing rehabilitation as a critical component of ACLR management and suggest that adjunct therapies like ESWT, therapeutic ultrasound and platelet-rich plasma therapy could play a pivotal role in optimizing non-surgical and surgical outcomes. It applies mechanical force to the extracellular matrix, inducing cellular deformation, ion fluxes, and conformational changes in signaling pathways, which improve the cytoskeletal system and stimulate growth factor release. These effects promote cell proliferation, differentiation, and osteoinduction, accelerating the healing process at the tendon-bone junction[19].

Studies have shown that ESWT enhances revascularization, increases type II collagen production, and fosters neovascularization and extracellular matrix metabolism, resulting in better graft incorporation. Immunohistochemical analyses in animal models have highlighted the role of ESWT in augmenting neovascularization at the musculo-tendinous transition zone, contributing to improved biomechanical outcomes without significant changes to bone microarchitecture[20]. Additionally since ACLR induces an inflammatory response in the knee joint[21], ESWT seeks to reduce the inflammatory factors in the knee[22]. In animal models ESWT has demonstrated improved bone mineralization, greater trabecular bone volume, higher tensile strength, and enhanced fibrocartilage regeneration at the tendon-bone interface with both high-energy and low-energy[19,23].

ESWT in rotator cuff tendinopathy has been assessed due to similar rehabilitative goals and challenges to ACLR, particularly in pain management and functional recovery. Meta-analysis findings demonstrated that ESWT significantly reduced pain and improved shoulder function in patients who underwent rotator cuff tendinopathy with effects lasting up to 12 weeks[24]. The proposed mechanisms include improved microcirculation and metabolic activity through tissue oscillations as well as overstimulation analgesia leading to immediate pain relief. Additionally, gender differences in pain relief effectiveness were observed with males benefiting more than females in retrospective studies[25,26].

ESWT also demonstrated statistically significant effects in reducing pain and improving function in knee osteoarthritis with studies highlighting its superiority over control or other therapies in multiple patient-centered outcomes[27]. Key findings include significant reductions in pain at rest and improvements in total scores when ESWT was combined with standard care or exercise. These benefits were noted across various ESWT parameters, such as lower energy densities and moderate session frequencies. However, the certainty of evidence was consistently graded as very low due to methodological limitations, including heterogeneity in intervention protocols, short follow-up periods, and incomplete reporting of key parameters like energy density and treatment duration[27].

Our findings revealed that focused ESWT demonstrated better functional outcomes, such as Lysholm scores, although not significant compared with radial ESWT. Better ESWT outcomes were observed in studies with longer follow-up durations. This suggests that the effects of ESWT may take time to fully manifest. In contrast, Song et al[7] reported that improvements in Lysholm scores in the ESWT group were observed only within the first 6 weeks, potentially indicating an overstimulation effect of the ESWT method. However, the short duration of the study may have limited its ability to capture sustained or delayed benefits of ESWT on graft maturation and overall knee function. These results also highlight the potential of focused ESWT as a more effective modality for enhancing recovery in ACL rehabilitation.

A study by Delia et al[28] on patients with tennis elbow demonstrated that combining focused and radial ESWT provided superior pain reduction and functional improvement in the short-term to mid-term compared with focused ESWT alone. This suggests that integrating both modalities could leverage their complementary mechanisms, i.e. deep tissue healing from focused ESWT and superficial muscle relaxation and circulation improvements from radial ESWT, to achieve better outcomes in ACLR. Further research is needed to evaluate the benefits of such combined approaches.

Previous meta-analyses have primarily focused on pooled pain scores or general function without distinguishing between focused and radial ESWT. Our analysis expanded on this by exploring ESWT modalities. Nonetheless, the limited number of RCTs and their methodological inconsistencies remain major limitations.

The six studies highlighted various limitations that impeded definitive conclusions about ESWT. Weninger et al[14] noted the absence of a placebo group and variability in magnetic resonance imaging methods, which compromised the reliability of graft maturation assessments. Zhang et al[15] highlighted challenges in generalizing results due to an all-male sample and differences in rehabilitation protocols between groups. Rahim et al[6] faced logistical issues, including small sample sizes and non-randomized group assignments, and limited follow-up durations. Li et al[4] emphasized the lack of significant short-term efficacy while pointing out variations in tibial end graft maturation influenced by anatomical differences. Song et al[7] reported inconsistent results due to the absence of comprehensive imaging or biomechanical assessments while Wang et al[8] acknowledged that their short follow-up period and reliance on imaging rather than histological analysis limited the interpretation of tendon-bone healing processes. Across all studies, heterogeneity in ESWT protocols, rehabilitation adherence, and demographic representation further constrained the generalizability of findings.

While individual studies often reported significant improvements, the variability in design, protocols, and outcomes reduced the consistency of findings when pooled in the meta-analysis. The significant result for the Lysholm score in the ESWT group suggested that specific protocols may yield more reliable outcomes, emphasizing the need for standardized methodologies and larger, more homogenous trials in future research. Additionally, the inclusion of placebo-controlled designs will be critical to isolate the true effects of ESWT from potential placebo or confounding factors, ensuring the robustness of future findings. Long-term follow-up studies are essential to evaluate the sustainability of short-term benefits while a focus on diverse participant populations will help determine the broader applicability of ESWT. Ultimately, these steps will provide clearer guidance on the optimal application of ESWT in ACLR and its potential to improve clinical and functional outcomes.

| 1. | Bliss JP. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury, Reconstruction, and the Optimization of Outcome. Indian J Orthop. 2017;51:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Burton I. Combined extracorporeal shockwave therapy and exercise for the treatment of tendinopathy: A narrative review. Sports Med Health Sci. 2022;4:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lingeman JE. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Development, instrumentation, and current status. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:185-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li F, Xiao J, Chen JH, Fu XJ. Effects of divergent extracorporeal shock wave therapy on the function and stability of male knee joint after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2022;49:82-88. |

| 5. | Jenkins SM, Guzman A, Gardner BB, Bryant SA, Del Sol SR, McGahan P, Chen J. Rehabilitation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Review of Current Literature and Recommendations. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022;15:170-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rahim M, Ooi FK, Shihabudin MT, Chen CK, Musa AT. The Effects of Three and Six Sessions of Low Energy Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy on Graft Incorporation and Knee Functions Post Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Malays Orthop J. 2022;16:28-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Song Y, Che X, Wang Z, Li M, Zhang R, Wang D, Shi Q. A randomized trial of treatment for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction by radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang CJ, Ko JY, Chou WY, Hsu SL, Ko SF, Huang CC, Chang HW. Shockwave therapy improves anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Surg Res. 2014;188:110-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51282] [Article Influence: 10256.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Keshtkar A, Salimi M, Karimi A. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy after ACL repair: A systematic review and meta analysis. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | COCHRANE handbook Chapter 16.1.3.2: Imputing standard deviations for changes from baseline. [cited 26 August 2025]. Available from: https://training-noproxy.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v5.0.0/chapter_16/16_1_3_2_imputing_standard_deviations_for_changes_from_baseline.htm. |

| 12. | Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, Thomas J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 3409] [Article Influence: 487.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 42540] [Article Influence: 1466.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 14. | Weninger P, Thallinger C, Chytilek M, Hanel Y, Steffel C, Karimi R, Feichtinger X. Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy Improves Outcome after Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with Hamstring Tendons. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang S, Wen A, Li S, Yao W, Liu C, Lin Z, Jin Z, Chen J, Hua Y, Chen S, Li Y. Radial Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Enhances Graft Maturation at 2-Year Follow-up After ACL Reconstruction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10:23259671221116340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shin J, Rhim HC, Kim J, Guo R, Elshafey R, Jang KM. Use of extracorporeal shockwave therapy combined with standard rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saueressig T, Braun T, Steglich N, Diemer F, Zebisch J, Herbst M, Zinser W, Owen PJ, Belavy DL. Primary surgery versus primary rehabilitation for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:1241-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | de Jonge R, Máté M, Kovács N, Imrei M, Pap K, Agócs G, Váncsa S, Hegyi P, Pánics G. Nonoperative Treatment as an Option for Isolated Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2024;12:23259671241239665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schleusser S, Song J, Stang FH, Mailaender P, Kraemer R, Kisch T. Blood Flow in the Scaphoid Is Improved by Focused Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Feichtinger X, Monforte X, Keibl C, Hercher D, Schanda J, Teuschl AH, Muschitz C, Redl H, Fialka C, Mittermayr R. Substantial Biomechanical Improvement by Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy After Surgical Repair of Rodent Chronic Rotator Cuff Tears. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:2158-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hunt ER, Jacobs CA, Conley CE, Ireland ML, Johnson DL, Lattermann C. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction reinitiates an inflammatory and chondrodegenerative process in the knee joint. J Orthop Res. 2021;39:1281-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Notarnicola A, Moretti L, Tafuri S, Panella A, Filipponi M, Casalino A, Panella M, Moretti B. Shockwave therapy in the management of complex regional pain syndrome in medial femoral condyle of the knee. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:874-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang CJ, Wang FS, Yang KD, Weng LH, Sun YC, Yang YJ. The effect of shock wave treatment at the tendon-bone interface-an histomorphological and biomechanical study in rabbits. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xue X, Song Q, Yang X, Kuati A, Fu H, Liu Y, Cui G. Correction: Effect of extracorporeal shockwave therapy for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25:507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pellegrino R, Di Iorio A, Brindisino F, Paolucci T, Moretti A, Iolascon G. Effectiveness of combined extracorporeal shock-wave therapy and hyaluronic acid injections for patients with shoulder pain due to rotator cuff tendinopathy: a person-centered approach with a focus on gender differences to treatment response. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yoon SY, Kim YW, Shin IS, Moon HI, Lee SC. Does the Type of Extracorporeal Shock Therapy Influence Treatment Effectiveness in Lateral Epicondylitis? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:2324-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oliveira S, Andrade R, Valente C, Espregueira-Mendes J, Silva F, Hinckel BB, Carvalho Ó, Leal A. Mechanical-based therapies may reduce pain and disability in some patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Knee. 2022;37:28-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Delia C, Santilli G, Colonna V, Di Stasi V, Latini E, Ciccarelli A, Taurone S, Franchitto A, Santoboni F, Trischitta D, Nusca SM, Vetrano M, Vulpiani MC. Focal Versus Combined Focal Plus Radial Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy in Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy: A Retrospective Study. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2024;9:201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/