Published online Aug 18, 2024. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v15.i8.807

Revised: July 6, 2024

Accepted: July 17, 2024

Published online: August 18, 2024

Processing time: 99 Days and 14.8 Hours

Congenital knee dislocation (CKD) is a rare condition, which accounts for 1% of congenital hip dislocations. It can present as an isolated condition or coexist with other genetic disorders. Treatment options include serial casting, percutaneous quadriceps recession, and V-Y quadricepsplasty (VYQ). The pathogenesis and hereditary patterns of CKD are not fully understood, with most cases being familial. CKD is usually managed immediately after birth. However, in this report, the patient was neglected for 2 years.

A 2-year-old girl with bilateral CKD after birth presented to our hospital after failed serial casting; the patient had seizures and limited access to healthcare because of her family’s low socioeconomic status. Her birth was noted for a breech presentation accompanied by oligohydramnios. The delivery took a long time, requiring immediate medical interventions. As an infant, she had chronic diseases, including a small patent ductus arteriole, multicystic dysplastic kidney disease, and epilepsy. She was found to have a bilateral knee dislocation of ap

This report highlights the importance of early intervention and recommends extensive studies of the management in similar cases.

Core Tip: Congenital knee dislocation is a rare condition, which accounts for 1% of congenital hip dislocations. According to a previous study, patients must be managed after birth immediately or up to 3 months. However, in the present case, the patient’s condition was neglected for 2 years for many reasons. Although in the literature V-Y quadricepsplasty (VYQ) was performed, in our surgical approach, VYQ plus semitendinosus and sartorius transfer were performed to fill the gap and increase muscle power. The outcome was satisfactory at 6 months follow up.

- Citation: Qasim OM, Abdulaziz AA, Aljabri NK, Albaqami KS, Suqaty RM. Neglected congenital bilateral knee dislocation treated by quadricepsplasty with semitendinosus and sartorius transfer: A case report. World J Orthop 2024; 15(8): 807-812

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v15/i8/807.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v15.i8.807

Congenital knee dislocation (CKD), or genu recurvatum congenitum, can be an unexpected finding after delivery. It was initially identified by Chatelain in 1822[1,2]. In the 1960s, the term CKD, defined as the forward displacement of the proximal tibia on the femoral condyles, was recognized as including all hyperextended knees present at birth[1]. CKD is a rare condition that affects women more than men. It accounts for 1% of congenital hip dislocations and affects 1/100000 live births[1,3]. CKD can present as an isolated condition or coexist with other genetic disorders such as musculoskeletal, clubfoot, or hip dislocation and, neurologically, as myelomeningocele, or it can be associated with other syndromes such as arthrogryposis multiplex, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or Larsen’s syndrome[4].

To categorize CKD, multiple classification methods have been proposed using radiographic observations of the femorotibial relationship and classified into grade I (simple recurvatum), grade II (subluxation), and grade III (dislocation)[5]. The pathogenesis and hereditary patterns for CKD are not fully understood because most cases are familial. In contrast, other cases were associated with intrauterine factors such as oligohydramnios, breech presentation, or lack of an intrauterine space[4].

Treatment options include serial casting, percutaneous quadriceps recession, and V-Y quadricepsplasty (VYQ)[5]. Surgical treatment is typically recommended for delayed presentation, conservative treatment failure, or syndromic involvement. Among the surgical approaches available, VYQ is considered the most common, and it was described initially by Curtis and Fisher[2] in 1969[5,6].

Herein, we report the case of a 2-year-old girl who presented to the clinic with a hyperextended knee that was diagnosed later as CKD and was treated with VYQ with semitendinosus and sartorius transfer technique as a mana

A 2-year-old girl presented to our orthopedic clinic with a bilateral hyperextended knee after birth.

The patient consulted another orthopedic doctor who managed her condition with serial casting when she was 3 months old. Her parents were not cooperative and neglected her for a long time. Consequently, the casting was ineffective, and she could not walk or crawl because of the deformity.

She was born at full term at breech presentation, with an average birth weight of 2.8 kg, and was delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery. Bilateral hyperextension of the knee joint was noticed after birth. The delivery of the infant’s head took longer, leading to concerns regarding respiratory status that required immediate medical inter

The patient experienced seizures and lived in a peripheral area where she had limited access to healthcare facilities. Her parents have low socioeconomic status, which is why she was neglected.

Regarding maternal history, her mother was pregnant with her at the age of 36 years (gravida 13 para 10 + 2) and did not receive appropriate antenatal care during her pregnancy. She had two intrauterine fetal deaths in the past. The causes of these fetal deaths were unknown despite a thorough investigation. Notably, the parents have consanguinity as first-degree cousins.

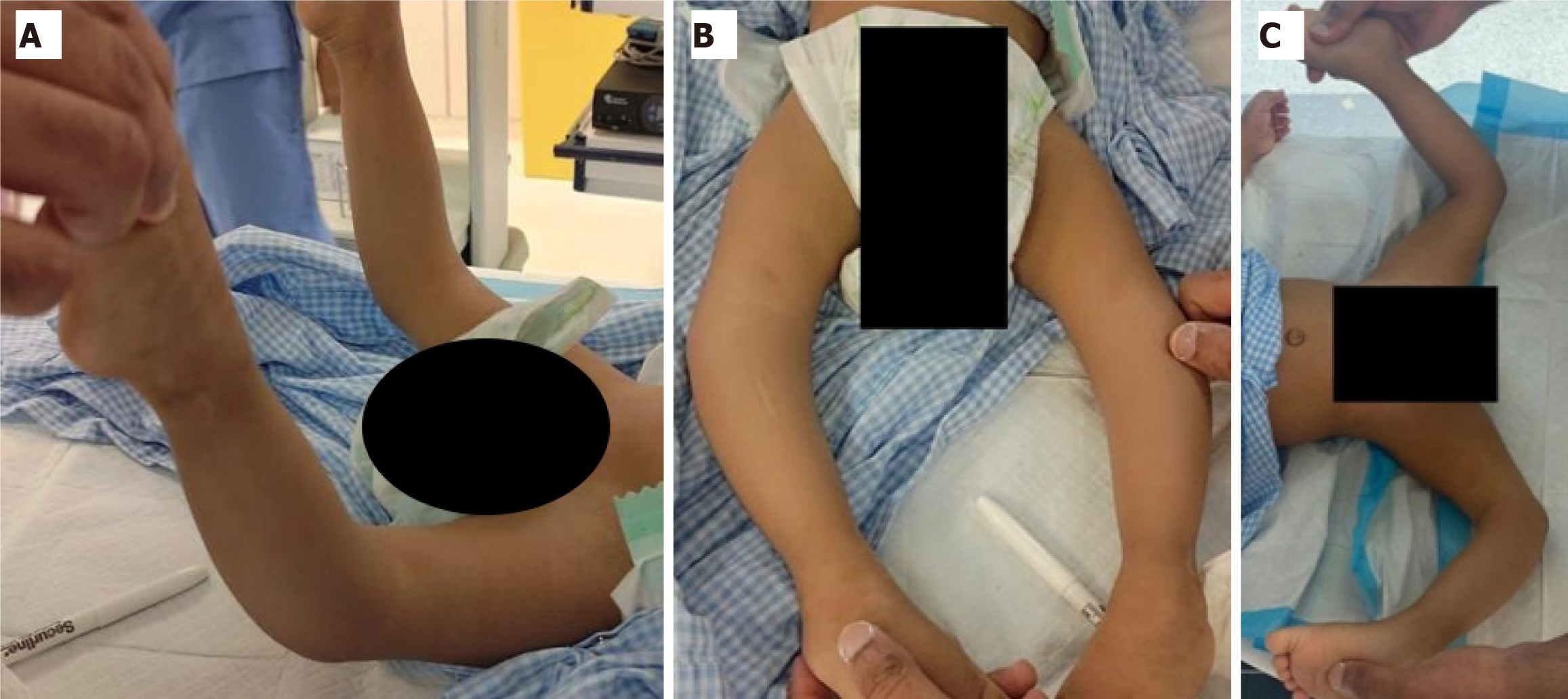

The patient was conscious, alert, and active with regular feeding, with stable vital signs. On local examination, she was found to have bilateral knee dislocation of approximately (-90°) on hyperextension by goniometry (Figure 1A). No anterior skin grooves were noted (Figure 1B). Subsequent careful manipulation was performed in attempts of reduction, and the knee angle was (10°) on hyperextension by goniometry (Figure 1C). In addition, the patient did not experience pain during active or passive range of motion (ROM).

The results of the chromosomal analysis and constitutional and peripheral blood tests were normal. The parents were advised to undergo genetic counseling and a microarray test to exclude the presence of chromosomal microdeletions or duplications. No apparent abnormalities were seen in the preoperative laboratory.

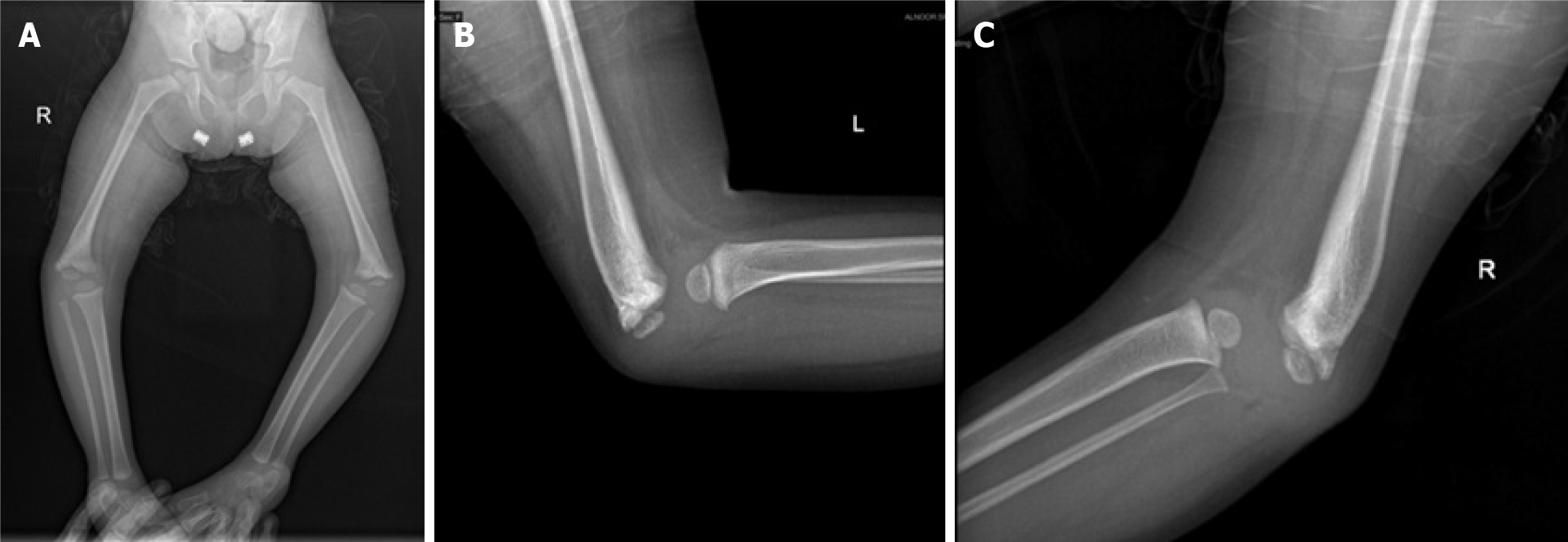

Plan X-ray imaging of lower limbs and anterior-posterior and lateral X-ray views (Figure 2) showed bilateral grade III knee dislocation according to the classification by Abdelaziz and Samir[5].

The final diagnosis was neglected bilateral CKD.

The treatment options for knee dislocation include serial casting, percutaneous quadriceps recession, and VYQ. Other doctors performed serial casting many times; however, no improvements were noted, so a definitive approach of VYQ was selected. A multidisciplinary team from different specialties evaluated the patient, and medical interventions were optimized.

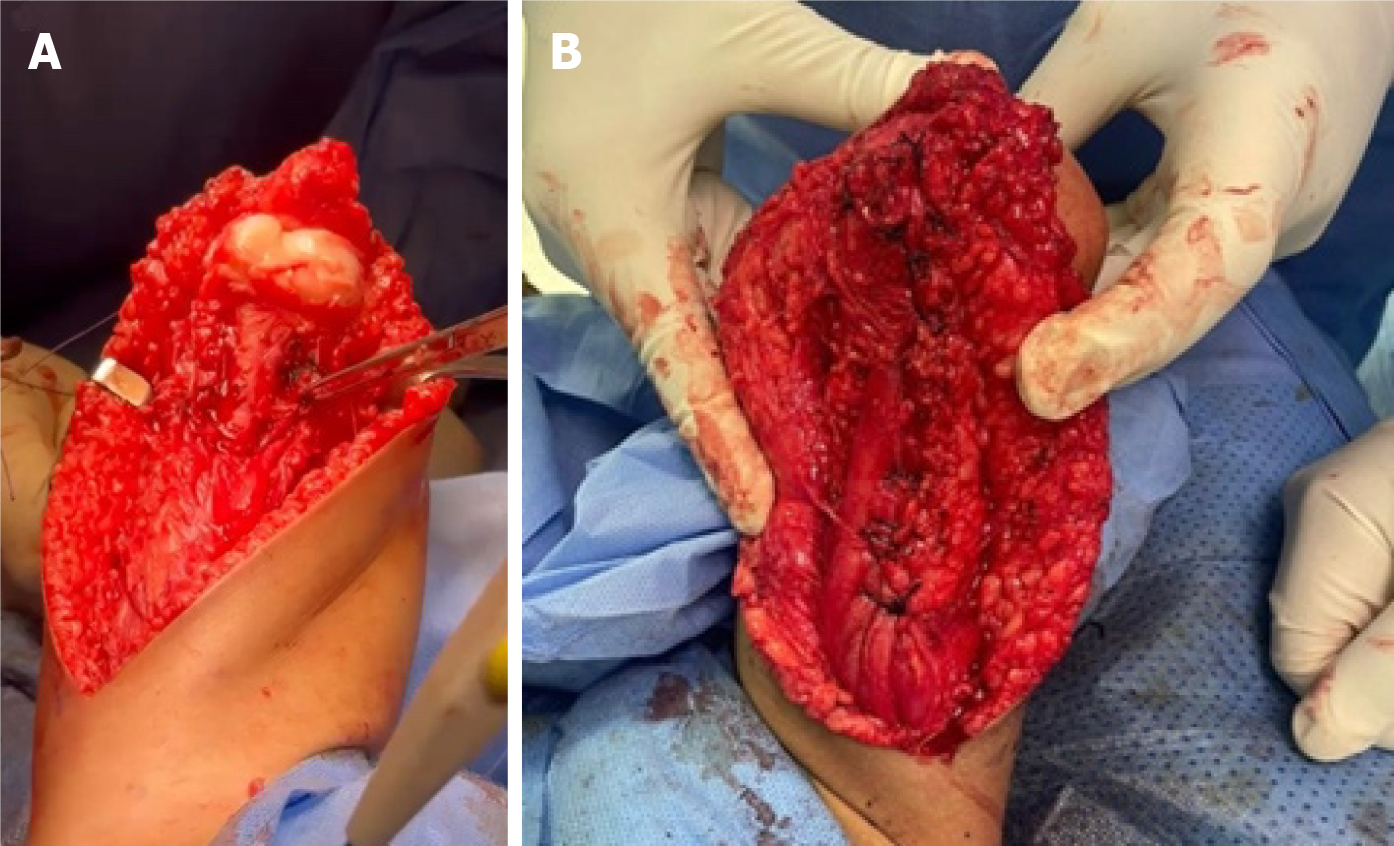

The surgery was performed in a supine position under general anesthesia, a foley catheter was applied, and sterile prepping and rapping were done for the lower limbs. Hemostasis was maintained with cautery, the patella was identified by needed insertion under X-ray guidance, anterolateral incision of the thigh to anteromedial was made, followed by superficial and deep dissection, and VYQ was performed through rectus femoris release of lateral collateral ligaments and then partial release of medial collateral ligaments (Figure 3). The knee capsule was opened, and the semitendinosus tendon was taken from its insertion to cover the anterior aspect of the thigh and attached to the rectus femoris to cover the gap. Knee reduction was confirmed under C-arm, and the wound was closed in layers with Monocryl. She received 1 unit of packed red blood cells in the operation room.

A bilateral above-knee cast was applied, and the cast window was made to check the wound after surgery. The wound was clean, with no discharges or signs of inflammation. The patient was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit and stayed there for 1 day. The next day, she was moved to the ward and was discharged after 2 days.

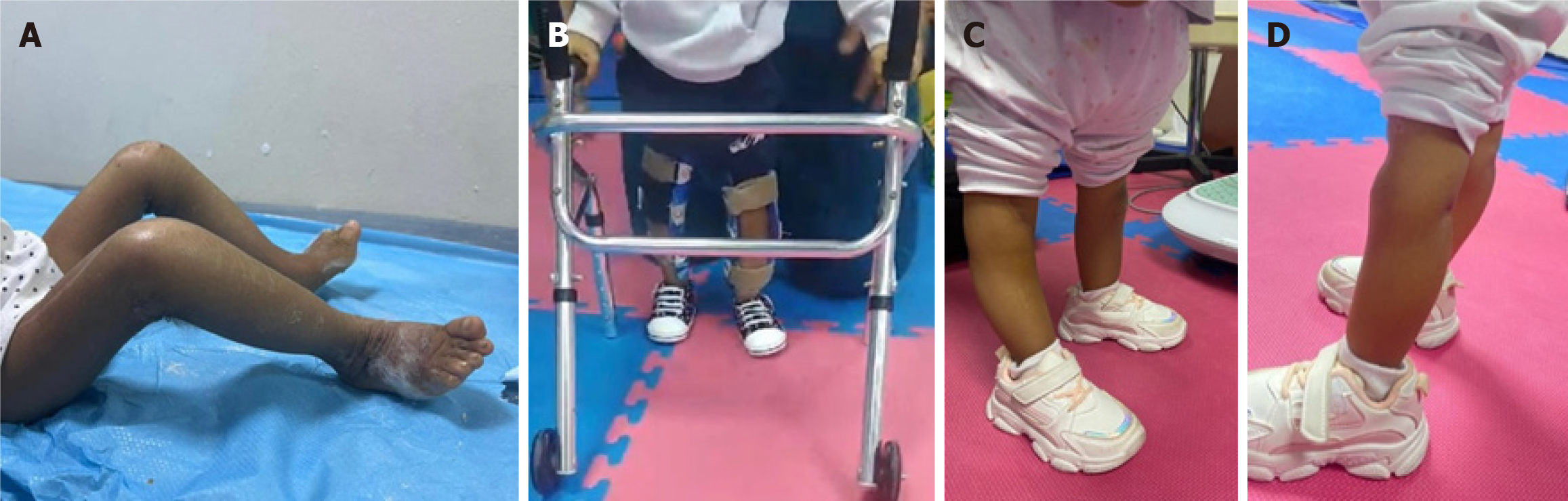

The patient was followed up in the outpatient orthopedic and physiotherapy clinic for 6 months after surgery. The first follow-up visit was made 2 weeks after surgery. The wound was inspected through the window; it was dry and clean with no signs of inflammation. In the second follow-up (2 months after surgery), the cast was removed, the wound was dry and clean with no sign of inflammation, the extent of right knee flexion was 90°, and the left knee was 100° at flexion as measured by a goniometer. The tone was normal in both limbs, and muscle power was two out of five in both limbs (Figure 4A). She was referred to a physiotherapist and followed up every week regularly. On the third follow-up (4 months after surgery), she could stand with minimal assistance and take one step with maximal assistance, the extent of right knee flexion was 110°, and left knee flexion was 100° as measured by a goniometer. The tone was normal, and muscle power was two out of five in both limbs. Some instability and hyperextension were noted when standing and walking specifically in the right knee; however, this was managed using a knee cage (Figure 4B). On the fourth follow-up (6 months after surgery), she could stand alone and take two steps without assistance, and the knee hyperextension was resolved. The extent of right knee flexion was 120°, and left knee flexion was 130° measured by a goniometer. The tone was normal, and the muscle power was three out of five in both limbs (Figure 4C and D).

In this report, we describe the case of a 2-year-old girl who was referred to our hospital for bilateral knee dislocation. The pregnancy was difficult, and labor was prolonged; despite the breech presentation and oligohydramnios, she was born via spontaneous vaginal delivery. The exact etiology of CKD is unknown; however, intrauterine[7] or genetic factors may be contributing factors, particularly in cases of consanguinity[8].

In this case, the patient presented late compared with other cases where the average age of presentation is 3 months[5]. In other studies, the presenting age was 1 month[6]. The late presentation of our patient made the treatment and achievement of surgical success more challenging.

Regarding the dislocation grade and prognosis, the extent of hyperextension must be initially evaluated to classify the dislocation. A study published in 2011 created a new classification based on the range of passive flexion, extent of hyperextension, and femorotibial relationship on radiographic X-ray image: Grade I, > 90° of flexion in ROM; Grade II, 30°-90° of flexion; and Grade III, < 30° of flexion[5]. They reported that ROM is a better indicator of disease severity; thus, selecting the treatment option based on the ROM is reliable. In the present case, as the patient was neglected, the degree of passive flexion was -10° before the neutral position, and it could be due to the late presentation that leads to the growth of surrounding tissue.

The absence of anterior skin grooves is a poor prognostic indicator, which could be due to the patient’s neglect and long-standing dislocation[8,9]. In this study, no skin grooves were identified in both limbs, which made conservative treatment challenging, as serial casting failed, which was another challenge. In contrast, a study reported the presence of anterior skin grooves as an excellent prognostic sign because the patient was treated conservatively by serial casting[9].

VYQ is associated with increased morbidity caused by a long incision with scarring, adhesions, wound breakdown, and blood loss. Nevertheless, the patient was treated with VYQ considering her age, dislocation grade, and X-ray findings. Although VYQ exhibits greater effectiveness and better outcomes in severe and challenging cases[5], the technique is performed as guided by Curtis and Fischer[2]. In addition, the semitendinosus and sartorius muscle tendons were transferred to the rectus femoris to increase the power and fill the gap after quadricepsplasty; to our knowledge, no study has described this technique.

This study has several limitations. The patient’s age presented a unique challenge, as more studies specific to this age group are needed. The limited availability of relevant studies and literature restricted the comparison and interpretation of findings. The dearth of literature limits a comprehensive understanding of the condition and its management in this age group.

Thus, these limitations must be considered when interpreting the study’s findings and generalizing the results. Future studies addressing these limitations could contribute to a reliable understanding of the condition and its management in this age group.

We have presented a unique case of neglected bilateral CKD that was successfully treated with VYQ with semitendinosus and sartorius transfer to the rectus femoris after serial casting failed. The outcomes of the 6-month follow-up were satisfactory. Physicians should be aware of CKD and manage it as early as possible to improve outcomes and minimize the interventions needed. Further studies are warranted to fill the knowledge gap in such neglected cases.

The authors thank Muhammed Jamal for following up with the patient and Muath Alahmadi, Sultan Aldebek, and Faisal Alghamdi for supporting this case report.

| 1. | Jacobsen K, Vopalecky F. Congenital dislocation of the knee. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Curtis BH, Fisher RL. Heritable congenital tibiofemoral subluxation. Clinical features and surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1104-1114. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Mehrafshan M, Wicart P, Ramanoudjame M, Seringe R, Glorion C, Rampal V. Congenital dislocation of the knee at birth-Part I: Clinical signs and classification. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:631-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Palco M, Rizzo P, Sanzarello I, Nanni M, Leonetti D. Congenital and Bilateral Dislocation of the Knee: Case Report and Review of Literature. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2022;14:33926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdelaziz TH, Samir S. Congenital dislocation of the knee: a protocol for management based on degree of knee flexion. J Child Orthop. 2011;5:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Youssef AO. Limited Open Quadriceps Release for Treatment of Congenital Dislocation of the Knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37:192-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haga N, Nakamura S, Sakaguchi R, Yanagisako Y, Taniguchi K, Iwaya T. Congenital dislocation of the knee reduced spontaneously or with minimal treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:59-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Shah NR, Limpaphayom N, Dobbs MB. A minimally invasive treatment protocol for the congenital dislocation of the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:720-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yeoh M, Athalye-Jape G. Congenital knee dislocation: a rare and unexpected finding. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/