Published online Feb 18, 2024. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v15.i2.129

Peer-review started: October 19, 2023

First decision: November 29, 2023

Revised: December 8, 2023

Accepted: January 3, 2024

Article in press: January 3, 2024

Published online: February 18, 2024

Processing time: 110 Days and 4.6 Hours

The study investigates the connection between academic productivity and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships. Utilizing metrics like the H-index and Open Payments Database (OPD) data, it addresses a gap in understanding the relationship between scholarly achievements and financial outcomes, providing a basis for further exploration in this specialized medical field.

To elucidate the trends between academic productivity and industry earnings across foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowship programs in the United States.

This study is a retrospective analysis of the relationship between academic productivity and industry earnings of foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellow

Forty-eight foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships (100% of fellowships) in the United States with a combined total of 165 physicians (95.9% of physicians) were included. Mean individual physician (n = 165) total life-time earnings reported on the OPD website was United States Dollar (USD) 451430.30 ± 1851084.89 (range: USD 25.16-21269249.85; median: USD 27839.80). Mean physician (n = 165) H-index as reported on Scopus is 14.24 ± 12.39 (range: 0-63; median: 11). There was a significant but weak correlation between individual physician H-index and individual physician total life-time earnings (P < 0.001; Spearman’s rho = 0.334) and a significant and moderate positive correlation between combined fellowship H-index and total life-time earnings per fellowship (P = 0.004, Spearman’s rho = 0.409).

There is a significant and positive correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings at foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States. This observation is true on an individual physician level as well as on a fellowship level.

Core Tip: We determined there to be a statistically significant correlation between individual physician H-index and individual physician total life-time, non-research-related earnings reported on Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This finding remained true when collective H index of the faculty at a given orthopedic foot and ankle fellowship was correlated to collective industry payments to the faculty at that fellowship. Further efforts should seek to characterize any potential disadvantages to the high degree of industry involvement of the most academically productive foot and ankle surgeons.

- Citation: Anastasio AT, Baumann AN, Walley KC, Hitchman KJ, O’Neill C, Kaplan J, Adams SB. Academic productivity correlates with industry earnings in foot and ankle fellowship programs in the United States: A retrospective analysis. World J Orthop 2024; 15(2): 129-138

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v15/i2/129.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v15.i2.129

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act was established in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act[1]. The Sunshine Act served to authorize the establishment of a publicly accessible electronic record of physician financial relationships with industry termed the “Open Payments” public database[1]. The database, geared towards improved physician accountability for potential industry biases, requires the recording of all payments greater than USD 10 made to physicians from drug and device manufacturers. Payments are categorized as either general payments, ownership interests, or research payments[2]. The vast majority of payments to orthopedic surgeons are characterized as royalties and license fees (69%, USD 74.4 million) with consulting fees (13%, USD 13.9 million) and non-consulting services (5%, USD 5.8 million) also awarded as sizeable yearly payments[3].

The Open Payments Database (OPD) reveals substantial industry involvement within foot and ankle surgery, with 802 orthopedic foot and ankle surgeons receiving nearly USD 39 million from industry through 29442 transactions during a 3-year period[4]. Relationships with industry can be complex; some studies have revealed no association between industry involvement and positive research findings[5], whereas others have demonstrated a potential source of bias, with industry funding leading to a higher likelihood of positive outcome reporting regarding a specific implant or phar

A substantial body of work has explored the OPD across physician subspecialities, attempting to understand demographic trends in industry payments and delineate sources of potential bias in practice patterns[9-13]. However, no study to date has tabulated the total industry payments to the faculty at a particular foot and ankle fellowship program and explored the correlation with academic productivity of that fellowship. Thus, the purpose of this study was to elucidate the trends between research output and involvement in industry across foot and ankle fellowship programs. Our primary goal was to explore whether academic productivity at a particular fellowship correlates with industry compensation. Our hypothesis was that higher industry payments would be associated with increased total research productivity, defined via the H-index, at a given fellowship.

This study is a retrospective analysis of the relationship between academic productivity and industry earnings of foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships at an individual faculty level as well as a fellowship level. The current study used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) website (https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/search) for physician earnings and payments, the Scopus website for physician H-index (https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/

Data extraction was performed by one author. Data collected included H-index per individual physician, total life-time earnings per individual physician, total payments made to individual physician, combined H-index per fellowship, combined total life-time earnings per fellowship, average total life-time earnings per physician per fellowship, and average total life-time earnings per fellowship per H-index. For subgroup analysis, individual physicians were placed one of four groups depending on the quartile of their H-index.

Statistical analysis was completed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of the data based on sample size. Means between three or more groups were compared using the independent-samples median test with Bonferroni correction due to the non-parametric nature of the data and extreme outliers. Significance values were set at 0.05. Correlation was performed for continuous data using Spearman’s rho due to the non-parametric nature of the data. Frequency counts, summative data, and descriptive data were used for demographics.

There are a total of 48 foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States with a combined total of 172 physicians as fellowship faculty. Seven physicians were missing data on CMS and four physicians were missing an H-index on Scopus. Only physicians with compete CMS money data and H-index on Scopus (n = 165 physicians, 95.9%) were included in data analysis.

Mean individual physician (n = 165 physicians) total life-time earnings reported on the CMS website was USD 451430.30 ± USD 1851084.89 (range: USD 25.16-21269249.85; median: USD 27839.80). Mean individual physician (n = 165 physicians) H-index as reported on H-index is 14.24 ± 12.39 (range: 0-63; median: 11). See Table 1 below for more information on individual physicians who are faculty at foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States with the top five total-life time earnings.

| Physician ranking | H-index | Total life-time earnings in USD | Overall payments |

| 1 | 58 | 21269249.85 | 694 |

| 2 | 3 | 6660954.43 | 2028 |

| 3 | 21 | 5215497.93 | 1293 |

| 4 | 24 | 4409146.87 | 591 |

| 5 | 22 | 3420158.94 | 903 |

Mean combined physician H-index reported on Scopus per fellowship (n = 48 fellowships) was 48.94 ± 38.92 (range: 9-187; median: 35.50). Mean combined physician life-time earnings reported on CMS per fellowship was USD 1551791.66 ± USD 4136091.64 (range: USD 8668.93-21274853.70; median: USD 359425.24). See Table 2 below for more information on fellowship programs for foot and ankle orthopedic surgery in the United States.

| Fellowship ranking | Total life-time earnings per fellowship | Mean total life-time earnings per physician per fellowship | Total H-index per fellowship | Total life-time earnings per fellowship per h index |

| 1 | 21274853.70 | 10637426.85 | 60 | 354580.90 |

| 2 | 20016633.67 | 2859519.10 | 107 | 187071.34 |

| 3 | 4553357.43 | 650479.63 | 187 | 24349.50 |

| 4 | 3383361.89 | 676672.38 | 53 | 63837.02 |

| 5 | 2534816.19 | 1267408.10 | 57 | 44470.46 |

| 6 | 2454950.69 | 818316.90 | 52 | 47210.59 |

| 7 | 1971933.15 | 657311.05 | 29 | 67997.69 |

| 8 | 1839321.97 | 919660.99 | 11 | 167211.09 |

| 9 | 1534450.54 | 306890.11 | 46 | 33357.62 |

| 10 | 1473486.49 | 245581.08 | 67 | 21992.34 |

| 11 | 1379087.01 | 1379087.01 | 23 | 59960.30 |

| 12 | 1300744.31 | 260148.86 | 94 | 13837.71 |

| 13 | 1197536.88 | 598768.44 | 11 | 108866.99 |

| 14 | 1018902.47 | 254725.62 | 81 | 12579.04 |

| 15 | 792190.87 | 132031.81 | 86 | 9211.52 |

| 16 | 659032.20 | 164758.05 | 53 | 12434.57 |

| 17 | 637897.63 | 159474.41 | 27 | 23625.84 |

| 18 | 629068.07 | 314534.04 | 21 | 29955.62 |

| 19 | 592739.33 | 118547.87 | 75 | 7903.19 |

| 20 | 504161.78 | 252080.89 | 29 | 17384.89 |

| 21 | 501127.63 | 100225.53 | 106 | 4727.62 |

| 22 | 437773.15 | 87554.63 | 165 | 2653.17 |

| 23 | 397822.34 | 132607.45 | 25 | 15912.89 |

| 24 | 376893.59 | 125631.20 | 36 | 10469.27 |

| 25 | 341956.88 | 68391.38 | 58 | 5895.81 |

| 26 | 333624.90 | 111208.30 | 11 | 30329.54 |

| 27 | 270203.44 | 90067.81 | 19 | 14221.23 |

| 28 | 261673.77 | 87224.59 | 101 | 2590.83 |

| 29 | 257580.01 | 85860.00 | 30 | 8586.00 |

| 30 | 230313.03 | 57578.26 | 24 | 9596.38 |

| 31 | 192293.20 | 48073.30 | 35 | 5494.09 |

| 32 | 170156.75 | 42539.19 | 91 | 1869.85 |

| 33 | 132455.07 | 66227.54 | 46 | 2879.46 |

| 34 | 117478.39 | 39159.46 | 36 | 3263.29 |

| 35 | 95286.89 | 15881.15 | 91 | 1047.11 |

| 36 | 87086.03 | 21771.51 | 15 | 5805.74 |

| 37 | 78504.91 | 39252.46 | 24 | 3271.04 |

| 38 | 76441.36 | 38220.68 | 29 | 2635.91 |

| 39 | 75612.14 | 25204.05 | 11 | 6873.83 |

| 40 | 61503.60 | 15375.90 | 34 | 1808.93 |

| 41 | 58786.54 | 58786.54 | 9 | 6531.84 |

| 42 | 42676.26 | 10669.07 | 36 | 1185.45 |

| 43 | 40725.72 | 20362.86 | 12 | 3393.81 |

| 44 | 28846.60 | 28846.60 | 25 | 1153.86 |

| 45 | 27864.96 | 13932.48 | 46 | 605.76 |

| 46 | 24067.73 | 8022.58 | 19 | 1266.72 |

| 47 | 10049.69 | 3349.90 | 33 | 304.54 |

| 48 | 8668.93 | 8668.93 | 13 | 666.84 |

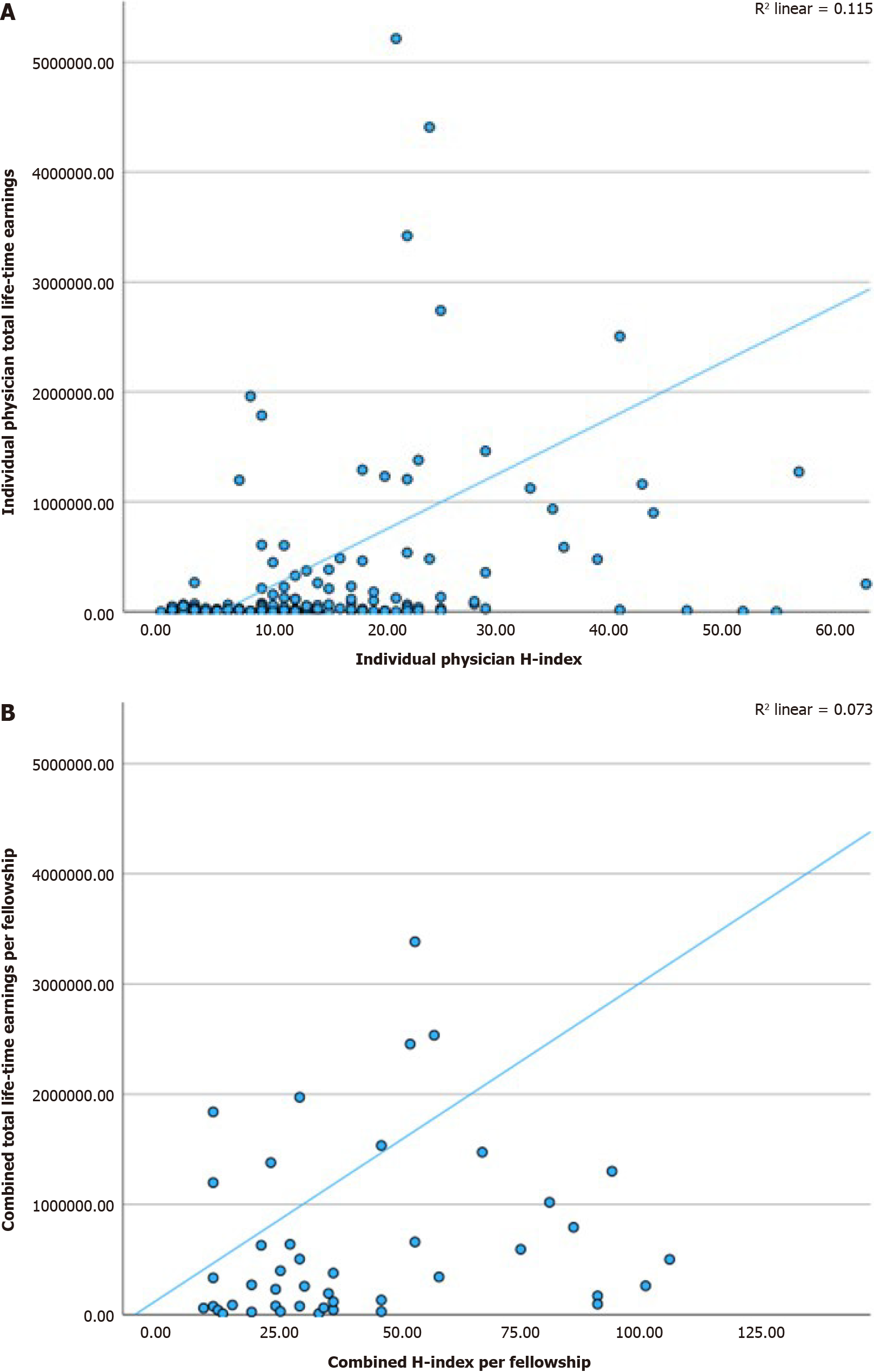

There was a significant but weak correlation between individual physician H-index and individual physician total life-time earnings reported on CMS (P < 0.001; Spearman’s rho = 0.334). See Figure 1A below for scatter plot with best fit line showing correlation between individual physician H-index who are fellowship faculty and total life-time earnings reported on CMS. There was a significant association between total life-time earnings and level of H-Index per individual physician by H-index quartile (P = 0.005). For subgroup post hoc analysis based on individual physician H-index, the four quartile group (n = 41 physicians) had significantly more total life-time earnings than the first quartile group (n = 42 physicians) (P = 0.004) and the second quartile group (n = 41 physicians) (P = 0.025). However, there was no significant difference between the total life-time earnings in the third quartile group and the fourth quartile group (P = 0.281). The first quartile group (n = 42 physicians) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 184342.91 ± 1024600.21 (range: USD 214.21-6660954.43; median: USD 14005.88). The second quartile group (n = 41 physicians) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 179626.75 ± 443691.76 (range: USD 437.84-1960346.56; median: USD 17894.85). The third quartile group (n = 41 patients) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 140744.38 ± 241444.40 (range: USD 25.16-1290811.98; median: USD 31056.22). The fourth quartile group (n = 41 patients) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 1307521.49 ± 3422970.09 (range: USD 242.61-21269249.85; median: USD 252327.86).

There was also a significant and moderate positive correlation between combined fellowship H-index and total life-time earnings per fellowship (P = 0.004, Spearman’s rho = 0.409). See Figure 1B below for scatter plot with best fit line showing correlation between combined fellowship H-index and total life-time earnings per fellowship.

Orthopedic surgeons are heavily influenced by their fellowship training programs with regards to practice patterns[14]. Thus, choice of fellowship may predict future academic engagement[15], subspeciality society participation, and involvement with industry as a consultant, design-team member, or paid educator. Therefore, this study aimed to build upon our understanding of the degree of industry involvement within foot and ankle fellowship programs. We sought to assess whether academic productivity at a particular fellowship correlated with industry compensation as recorded in the OPD. As a secondary outcome, we assessed whether higher H index of an individual surgeon is correlated with larger net industry earnings.

We determined there to be a statistically significant and moderate positive correlation between combined fellowship H-index and total life-time earnings per fellowship, further indicating that academic productivity of an orthopedic foot and ankle fellowship group correlates to overall industry involvement. In addition, we found a statistically significant correlation between individual physician H-index and individual physician total life-time earnings reported on CMS. While this result achieved only a weak correlation based on Spearman’s rho (0.334) given substantial heterogeneity within the data, examination of the actual numbers reveals a clearer trend. The first quartile group (n = 42 physicians) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 184342.91 ± 1024600.21 (range: USD 214.21-6660954.43; median: USD 14005.88). The second quartile group (n = 41 physicians) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 179626.75 ± 443691.76 (range: USD 437.84-1960346.56; median: USD 17894.85). The third quartile group (n = 41 patients) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 140744.38 ± 241444.40 (range: USD 25.16-1290811.98; median: USD 31056.22). The fourth quartile group (n = 41 patients) had a mean total life-time earnings of USD 1307521.49 ± 3422970.09 (range: USD 242.61-21269249.85; median: USD 252327.86). These data provides strong support to the notion that surgeons who are extensively involved with industry have a substantial academic background.

The relationship between academic involvement and industry support for research activity is straightforward: academicians are more likely to receive monetary backing to carry out investigation of a specific pharmaceutical or surgical implant. Industry-funded research is the topic of substantial debate with concerns for conflict of interest and bias factoring in to the legitimacy of the findings[16-20]. The most obvious case example is the tobacco industry funding faulty research regarding smoking and use of tobacco products[21-25]. Several authors have raised concern regarding bias related to industry funding of research within orthopedics as well[26,27]. For example, Shah et al[26] demonstrated a higher likelihood for industry-funded studies to report positive results than studies funded from other sources. While cash or cash-equivalent payments represent the majority of the payment types to foot and ankle surgeons, there is substantial contribution from industry to support research efforts within foot and ankle[28].

Several studies have sought to investigate the impact of industry funding on reporting of positive (or favorable) results within foot and ankle surgery. Cole et al[29] revealed a large percentage of undisclosed conflicts of interest within systematic reviews related to Achilles tendon rupture. Despite this finding, these authors note that the lack of conflict of interest disclosure did not increase the likelihood of a positive finding in the results of the intervention being investigated. Donoughe at al. evaluated the association between positive outcome reporting in total ankle arthroplasty research, and determined that payments were not significantly correlated with favorable outcomes for a specific implant[30]. While these studies generally indicate a lack of substantial industry influence in the reporting of positive results within foot and ankle, these results are inconclusive and non-generalizable. Further work should seek to identify other potential sources of bias within foot and ankle surgery research.

While industry funding of research is a topic of much debate, our study sought to characterize payments which were made for reasons specifically not related to research, including for food and drink, travel, cash payments, and cash-equivalent payments. We determined that payments unrelated to research are correlated with H index – a less intuitive finding than the observation that research payment correlates with H index. This finding was true both at the individual surgeon level and at the fellowship-grouped level. Surgeons with more academic influence may be able to command higher consulting fees and may be more likely to be approached with implant design-team opportunities. Benefits of this relationship include more incentive for foot and ankle practitioners to participate in research, which often comes at a significant time and opportunity cost for surgeons with busy surgical practices. Potential disadvantages of a system where heavy academic involvement is rewarded by larger industry payouts are poorly investigated in the literature. Surgeons may be encouraged to publish a higher total number of manuscripts rather than focusing on areas of highest impact. Additionally, surgeon-leaders with considerable academic influence who are heavily involved with foot and ankle fellowship education may be the most problematically impacted by loyalty to a specific implant manufacturer. Further research should seek to expand upon these findings and quantify the repercussions of heavy industry involve

Limitations of this analysis include lack of granularity regarding specific fellowship or individual identifiers. Despite the public availability of the information contained within the OPD, we attempted to avoid personally-identifying information contained within this manuscript, as small fellowship programs with only several faculty members may preclude full anonymity. Moreover, we utilized H index as a surrogate for academic involvement. While the H index does correlate with number of publications and citation count of a given author’s combined research works, this metric has come under criticism as overly simplistic and failing to capture actual impact of scientific investigation[31]. As a final limitation, we did not control for the age of a given surgeon or the average age of the surgeons at a given fellowship, as this information was not readily available online. Furthermore, high fellowship total life-time earnings may be a result of a single surgeon’s high earnings or multiple surgeons’ high earnings, and our statistical analysis did not account for this factor. As H index is associated with age[32], industry involvement may more closely be associated with more years of experience within foot and ankle surgery than with academic involvement. However, older surgeons who are employed in private practice may have very low H indices, and are unlikely to accrue the number of publications and citations necessary to be a part of the “Greater than 25 H-index” cohort in this investigation. Additionally, different institutions may have differing rules or attitudes towards these payments, which could not be accounted for and could skew data.

In conclusion, we determined there to be a statistically significant correlation between individual physician H-index and individual physician total life-time, non-research-related earnings reported on CMS. This finding remained true when collective H index of the faculty at a given orthopedic foot and ankle fellowship was correlated to collective industry payments to the faculty at that fellowship. Further efforts should seek to characterize any potential disadvantages to the high degree of industry involvement of the most academically productive foot and ankle surgeons.

The study opens the door for future research by revealing a significant positive correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships. Subsequent research could explore the underlying factors influencing this correlation, identifying causal mechanisms and potential interventions to enhance both academic productivity and financial outcomes in this specialized medical field. Additionally, future studies may look into the broader implications of these findings for the education and practice of foot and ankle orthopedic surgeons.

The study does not explicitly propose new theories. Instead, it focuses on investigating and establishing a correlation between academic productivity (measured by the H-index) and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships. The primary contribution lies in highlighting the relationship between scholarly achievements and financial outcomes in this specific medical field, without introducing novel theoretical frameworks.

The findings indicate a significant correlation between academic productivity (H-index) and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships. This contributes to our understanding of the relationship between scholarly achievements and financial outcomes. However, the study does not investigate specific factors influencing these correlations, leaving room for future research to explore the nuances further.

The study is a retrospective analysis. We utilized data from two primary sources: Scopus for academic productivity metrics, specifically the H-index, and the Open Payments Database (OPD) for industry earnings data. The research involved the examination of 48 foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States, covering 100% of such programs and 95.9% of physicians. Academic productivity was assessed through the H-index recorded from the Scopus website, while industry earnings were obtained from the OPD, encompassing total life-time earnings from 2015 to 2021. The novelty of the research lies in the comprehensive analysis of the correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings at both individual physician and fellowship levels within the context of foot and ankle orthopedic surgery, providing a unique perspective on the intersection of scholarly achievements and financial outcomes in this specialized medical field.

The main objectives of this study were to investigate the correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States. The study aimed to quantify academic productivity using the H-index and measure industry earnings through the OPD. The objectives that were realized include identifying a significant positive correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings at both individual physician and fellowship levels. The significance of realizing these objectives lies in shedding light on the intricate relationship between scholarly achievements and financial outcomes in this specialized medical field, providing a foundation for future research to delve deeper into the factors influencing this correlation and its implications for the field of foot and ankle orthopedic surgery.

This study investigates the relationship between academic productivity and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships in the United States. Key topics include individual physician and fellowship-level metrics, such as the H-index for academic productivity and total life-time earnings from the OPD. The study identifies a significant positive correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings, addressing the crucial link between scholarly achievements and financial outcomes in the field, providing valuable insights for future research in understanding these dynamics.

This retrospective analysis explores the correlation between academic productivity and industry earnings in foot and ankle orthopedic surgery fellowships across the United States. Examining individual physician and fellowship-level data from 48 programs, the study reveals a significant positive association between academic productivity (measured by the H-index) and industry earnings. The findings highlight the interconnections of scholarly achievements and financial outcomes in this specialized medical field, both at the individual physician and fellowship levels.

We would like to thank Dr. Keith Baldwin, MD, MSPT, MPH for his statistical consultation.

| 1. | Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the Physician Payment Sunshine Act and the Open Payments program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:519-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parisi TJ, Ferre IM, Rubash HE. The Basics of the Sunshine Act: How It Pertains to the Practicing Orthopaedic Surgeon. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:455-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Samuel AM, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Russo GS, Rathi VK, Grauer JN. Orthopaedic Surgeons Receive the Most Industry Payments to Physicians but Large Disparities are Seen in Sunshine Act Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3297-3306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pathak N, Galivanche AR, Lukasiewicz AM, Mets EJ, Mercier MR, Bovonratwet P, Walls RJ, Grauer JN. Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Surgeon Industry Compensation Reported by the Open Payments Database. Foot Ankle Spec. 2021;14:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Somerson JS, Comley MC, Mansi A, Neradilek MB, Matsen FA 3rd. Industry payments to authors of Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery shoulder arthroplasty manuscripts are accurately disclosed by most authors and are not significantly associated with better reported treatment outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matsen FA 3rd, Jette JL, Neradilek MB. Demographics of disclosure of conflicts of interest at the 2011 annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Narain AS, Hijji FY, Yom KH, Kudaravalli KT, Singh K. Cervical disc arthroplasty: do conflicts of interest influence the outcome of clinical studies? Spine J. 2017;17:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schiller JR, DiGiovanni CW. Foot and ankle fellowship training: a national survey of past, present, and prospective fellows. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Financial relationships between neurologists and Industry: The 2015 Open Payments database. Neurology. 2019;92:1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boas SR, Niforatos JD, Summerville L, Isbester K, Chaturvedi A, Wee C, Kumar AR. The Open Payments Database and Top Industry Sponsors of Plastic Surgeons: Companies and Related Devices. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:530e-532e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brauer PR, Morse E, Mehra S. Industry Payments for Otolaryngology Research: A Four-Year Analysis of the Open Payments Database. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haque W, Haque E, Hsiehchen D. Female dermatology journal editors accepting pharmaceutical payments: An analysis of the Open Payments database, 2013 to 2018. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:451-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Heckmann ND, Mayfield CK, Chung BC, Christ AB, Lieberman JR. Industry Payment Trends to Orthopaedic Surgeons From 2014 to 2018: An Analysis of the First 5 Years of the Open Payments Database. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:e191-e198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DePasse JM, Daniels AH, Durand W, Kingrey B, Prodromo J, Mulcahey MK. Completion of Multiple Fellowships by Orthopedic Surgeons: Analysis of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification Database. Orthopedics. 2018;41:e33-e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Haimowitz S, Veliky J, Forrester LA, Ippolito J, Beebe K, Chu A. Subspecialty Selection Impacts Research Productivity and Faculty Rank of Academic Orthopaedic Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:e31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elliott DB. Industry-funded research bias and conflicts of interest. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2013;33:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chapman S, Bhangu A. Ban on publishing industry funded research could harm surgical innovation. BMJ. 2014;348:g1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Smith R, Gøtzsche PC, Groves T. Should journals stop publishing research funded by the drug industry? BMJ. 2014;348:g171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Breault JL, Knafl E. Pitfalls and Safeguards in Industry-Funded Research. Ochsner J. 2020;20:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Plottel GS, Adler R, Jenter C, Block JP. Managing Conflicts and Maximizing Transparency in Industry-Funded Research. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2020;11:223-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Godlee F, Malone R, Timmis A, Otto C, Bush A, Pavord I, Groves T. Journal policy on research funded by the tobacco industry. BMJ. 2013;347:f5193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Malone RE. Changing Tobacco Control's policy on tobacco industry-funded research. Tob Control. 2013;22:1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Polito JR. Non-publication of tobacco funded research should extend to replacement nicotine studies funded by the drug industry. BMJ. 2013;347:f6740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Smith R. Arguments against publishing tobacco funded research also apply to drug industry funded research. BMJ. 2013;347:f6732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dunn AG, Coiera E. Should comparative effectiveness research ignore industry-funded data? J Comp Eff Res. 2014;3:317-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shah RV, Albert TJ, Bruegel-Sanchez V, Vaccaro AR, Hilibrand AS, Grauer JN. Industry support and correlation to study outcome for papers published in Spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:1099-104; discussion 1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | McDonnell JM, Dalton DM, Ahern DP, Welch-Phillips A, Butler JS. Methods to Mitigate Industry Influence in Industry Sponsored Research. Clin Spine Surg. 2021;34:143-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Casciato DJ, Mendicino RW. CMS Open Payments Database Analysis of Industry Payments for Foot and Ankle Surgery Research. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;61:1013-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cole WT, Hillman C, Corcoran A, Anderson JM, Weaver M, Torgerson T, Hartwell M, Vassar M. Financial Conflicts of Interest Among Systematic Review Authors Investigating Interventions for Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021;6:24730114211019725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Donoughe JS, Safavi KS, Rezvani A, Healy N, Jupiter DC, Panchbhavi VK, Janney CC. Industry Payments to Foot and Ankle Surgeons and Their Effect on Total Ankle Arthroplasty Outcomes. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021;6:24730114211034519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Koltun V, Hafner D. The h-index is no longer an effective correlate of scientific reputation. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0253397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kelly CD, Jennions MD. H-index: age and sex make it unreliable. Nature. 2007;449:403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Papazafiropoulou A, Greece S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY