INTRODUCTION

Hypertensive emergency (HE) is a critical medical condition presenting as a rapid and substantial elevation in blood pressure, which leads to a progressive impairment and potential failure of target organs[1]. This sudden spike in blood pressure can cause considerable harm to the body's physiological systems. It may also trigger numerous severe conditions, including hypertensive encephalopathy, acute stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute left heart failure, aortic dissection, and eclampsia[2]. Mortality statistics are sobering, with death rates possibly ascending to 6.9% in the acute phase of HE. Moreover, mortality and readmission rates can reach 11% within 90 days of the condition's onset. For a subset of patients with severe hypertension, the mortality rate may increase to 50% within 1 year[3]. Various precipitating factors can contribute to HE. These factors include discontinuation of antihypertensive medication, onset of acute infections, acute urinary retention, episodes of acute or chronic pain, ingestion of sympathomimetic drugs (e.g., cocaine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and amphetamines), panic attacks, and use of medicines inhibiting the effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastric mucosa protectors)[4]. The HE pathophysiology is related to the activation of sympathetic hypertonia and the release of vasoconstrictive substances, such as renin and angiotensin II. The surge in the activation and release of these substances abruptly elevates blood pressure over a short period[4].

To our knowledge, no case reports or clinical studies have documented cervical spondylotic radiculopathy (CSR)-induced HE. Here, we present a rare case of a 57-year-old female patient who presented with atypical symptoms of CSR, which was diagnosed during an outpatient consultation. After appropriate assessments were performed, the patient was scheduled to undergo anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF). During surgical preparation, when the patient was placed in the supine position for the procedure, blood pressure significantly increased (reaching as high as 270/100 mmHg) following minor cervical spine extension. Rapidly elevating the patient's head caused a gradual decline in blood pressure. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 57-year-old woman presented to our department in August 2022. She complained of pain in her neck and right upper limb, which had been persistent for the past 2 months.

History of present illness

The patient started experiencing neck and back pain 2 months ago, without an identifiable etiology, along with discomfort in the right upper limb and difficulty in posterior neck extension. These symptoms are aggravated during sitting or ambulation but alleviated following recumbency and rest. Orally administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were ineffective.

History of past illness

Despite having a decade-long history of diabetes, the patient had no hypertension or coronary heart disease, and effective glycemic control was achieved with oral metformin and acarbose. Blood pressure was measured twice daily before surgery, and the maximum reading of 148/74 mmHg was obtained.

Personal and family history

No personal and family history.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed a normal gait, pain-induced passively flexed cervical position, and remarkable limitation in cervical extension. The roof pressure test and the right brachial plexus pull test yielded positive results, whereas the bilateral paper clamp test yielded negative results. In the patient, muscle strength and tone in all limbs were normal. Neurologically, both Hoffman's and Babinski's signs were negative.

Laboratory examinations

Routine blood tests, liver function tests, biochemical assays, C-reactive protein levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate parameters were all within normal limits.

Imaging examinations

The cervical spine radiographs revealed various degrees of osteophyte formation and sclerosis on the edges of the C2–C7 vertebrae, along with a pronounced reduction in the intervertebral space at C6–C7 and calcification of the nuchal ligament. A computed tomography scan displayed the disappearance of the physiological curvature and inverting arch formation. The scan also showed a right posterior herniated disc in the C6–C7 space, which led to right nerve root canal stenosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine demonstrated a right-sided C6–C7 nucleus pulposus protrusion, which caused compression of the right C7 nerve root (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of CSR at the C6–C7 intervertebral level was made.

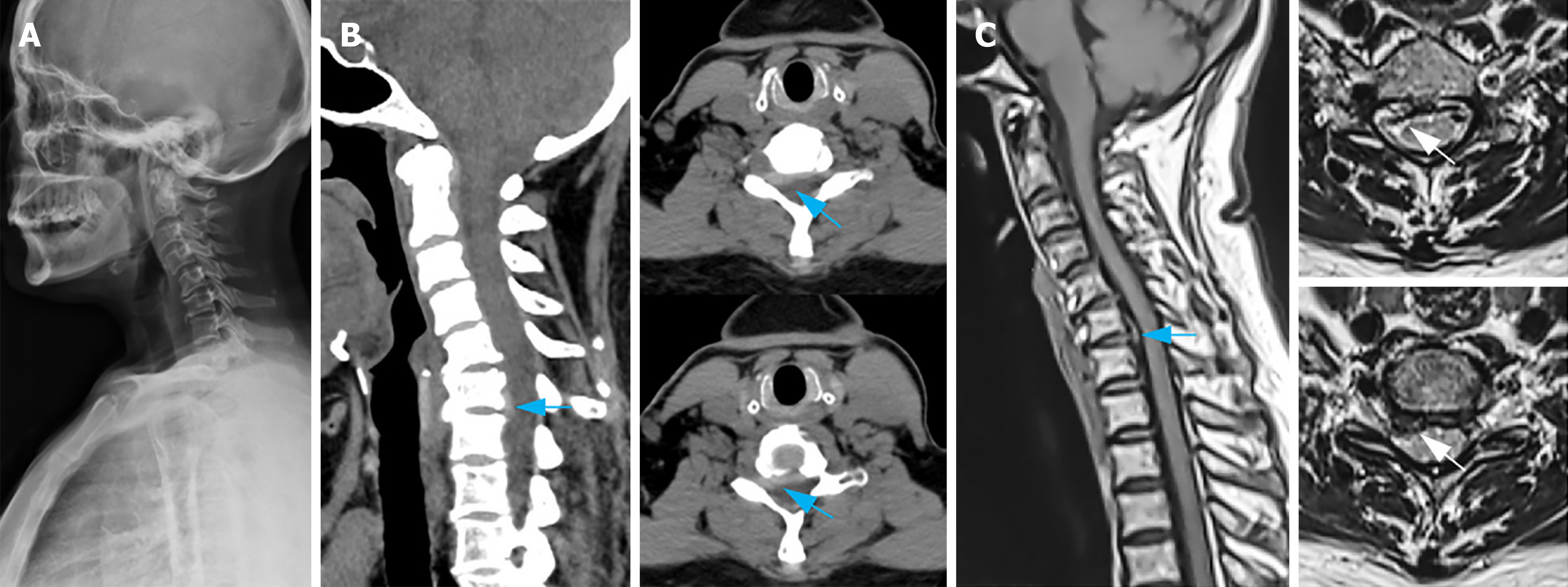

Figure 1 Preoperative imaging examinations.

A: A lateral plain film of the cervical vertebra depicts cervical vertebra's reversed arch, narrowed C6/7 space, and patchy calcification of the nuchal ligament; B: Cervical vertebra computerized tomography sagittal reconstruction and plain scan demonstrate an intervertebral disc prolapse and upward displacement in the C6/7 space, along with right nerve root canal stenosis (indicated by the blue arrow); C: Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging and plain scan of cervical vertebra present herniation and upward displacement of the intervertebral disc in the C6/7 space (indicated by the blue arrow), discontinuous intervertebral disc signal, and compression of the right C7 nerve root (indicated by the white arrow).

A preoperative electrocardiogram indicated sinus rhythm and normal findings. Color ultrasonography unveiled a normal size of the heart cavity, normal inner diameter of large blood vessels, and normal thickness of the ventricular septum and posterior wall of the left ventricle. The left ventricular systolic function was good, with an ejection fraction of 64%. However, cervical vascular ultrasonography unveiled bilateral carotid atherosclerosis with plaques. Yet, the bilateral vertebral arteries and internal carotid venous flow were unobstructed.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Once all surgical contraindications were excluded, the patient was prepared for ACDF under general anesthesia. After anesthesia was successfully induced, the patient was positioned supine with the neck being slightly extended. During this process, invasive monitoring detected a sudden elevation in arterial blood pressure from 150/85 to 270/100 mmHg. Immediately, the patient's neck position was readjusted from hyperextension to flexion, and the head was elevated. Following a 10-minute observation period, the blood pressure gradually decreased. Given these circumstances, the surgeons decided to abort the procedure and awaken the patient. After anesthesia reversal was achieved, the patient's blood pressure normalized to 130/90 mmHg, with a satisfactory return of limb motor function and skin sensation. The patient exhibited no previous medical history indicative of hypertension. Following consultation with the deputy chief of cardiology, the acute elevation in the patient's intraoperative blood pressure was concluded to be a possible result of cervical extension or anesthesia administration. Suggestions: Changes in patients' blood pressure must be continuously monitored. Antihypertensive medication should be initiated if hypertension is observed. If acute elevation of blood pressure is recurrent, sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerin may be administered for symptomatic relief. A final diagnosis of atypical CSR was made.

TREATMENT

Three days later, following an intragroup discussion, a decision to perform laminoplasty through a posterior approach and endoscopy-assisted C6/7 right nerve root canal nucleus pulposus discectomy procedures was made. Anesthesia was successfully administered, and the patient was positioned supine. Arterial blood pressure was invasively monitored to assess hemodynamic stability for 5 minutes. The blood pressure was consistently fluctuating between 120–140/80–100 mmHg. Once blood pressure stabilized, the patient was positioned prone without any significant changes noted in hemodynamics. Once the patient was successfully placed in the prone position, the surgical site was meticulously disinfected and sterile drapes were applied.

A 10-cm-long longitudinal incision was made, with each layer being successively cut through. After the paraspinal muscle was dissected, the C2 spinous process served as the localization marker for exposing the bilateral C4–C6 lateral mass. The lateral cortex of the left lamina was excised using an ultrasonic bone knife, thereby the "portal axis side" was formed. The bilateral cortex on the right side was incised to form the "door side", followed by the cautious elevation of the C4–C6 lamina and decompression of the spinal cord. An appropriately sized single-door plate was used to fix the "door side" of the C4 and C6 lamina. Portions of the C3 and C7 lamina were excised. Following thorough decompression, spinal cord distension was observed, and pulsation resumed. The C7 right nerve root was exposed using a foraminal lens. Three fragments of the broken nucleus pulposus tissue were extracted from the ventral axillary side of the C7 right nerve root by using the foraminal lens and crochet. When the crochet probe was reapplied, the nerve root was found to be relaxed, which indicated the completion of the operation (Figure 2).

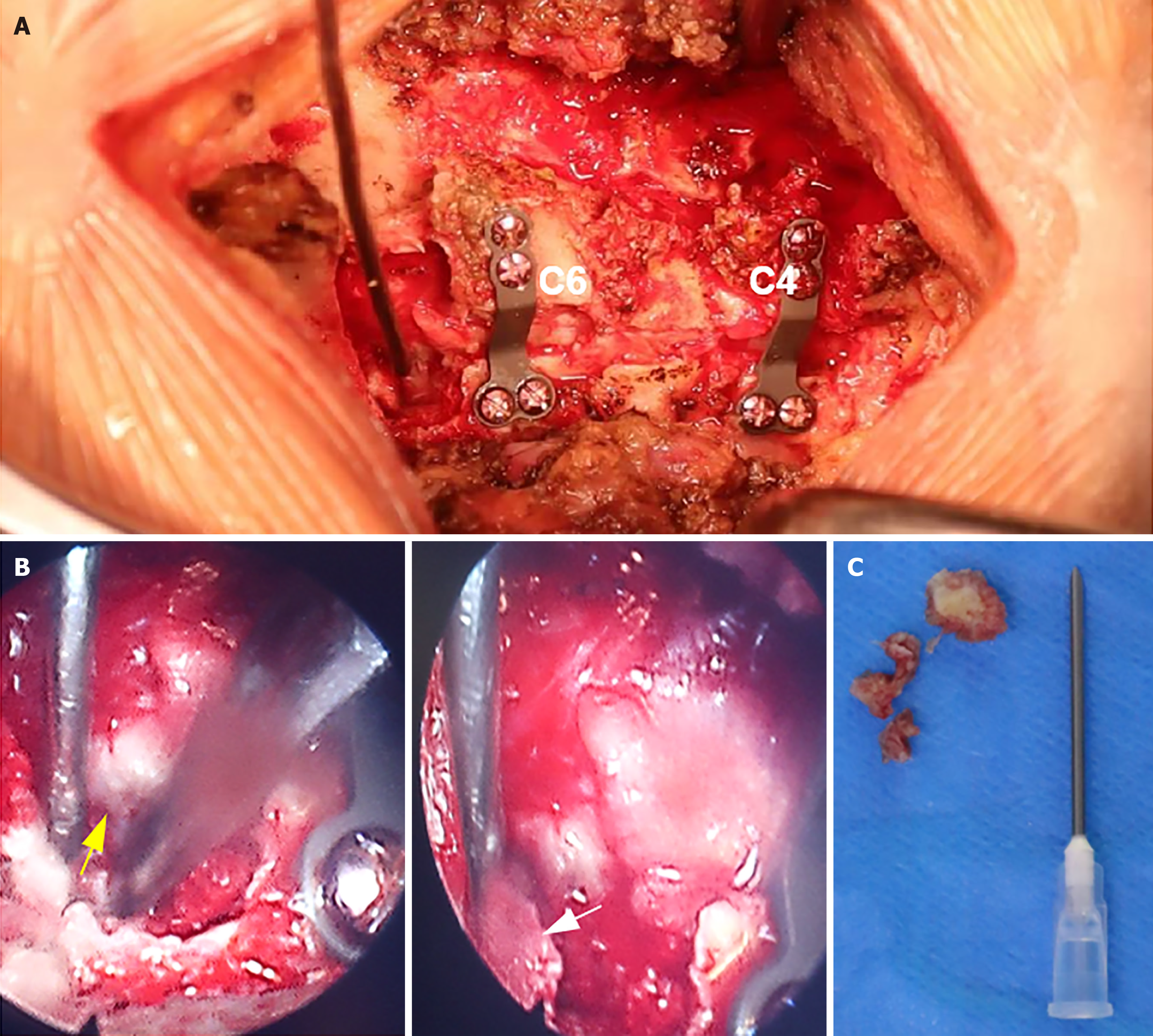

Figure 2 Intraoperative image.

A: The vertebral laminae of C4 and C6 were elevated, facilitating decompression of the spinal cord, followed by placement of an internal fixation plate; B: The ventral nucleus pulposus was extracted from the right nerve root of C7 using foraminal mirror-assisted extraction technique. During this procedure, the dural membrane (indicated by the yellow arrow) and excised free nucleus pulposus tissue (indicated by the white arrow) were visually observed; C: Intraoperatively obtained free nucleus pulposus tissue from the ventral aspect of the C7 nerve root.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

On the third postoperative day, pain in the neck and right upper extremity ceased. The sutures were removed on the 12th postoperative day, with the subsequent discharge of the patient from the hospital. A 6-month postoperative outpatient follow-up demonstrated markedly improved neck flexion and extension activities. MRI confirmed that the nucleus pulposus tissue was absent in the C7 nerve root canal (Figure 3). Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring exhibited no acute increase in blood pressure following excessive flexion or extension of the patient's neck (Figure 4). The patient was satisfied with the treatment effect.

Figure 3 Outpatient follow-up 6 months post-surgery.

A: X-ray examination of the cervical spine in lateral and hyperextension flexion positions displays a significant improvement in the cervical spine's range of motion; B: Magnetic resonance imaging at 6 months post-surgery: The herniated nucleus pulposus tissue of C6/7 has been eliminated, and the right C7 nerve has been entirely decompressed, with no signal from the nucleus pulposus tissue (indicated by the white arrow).

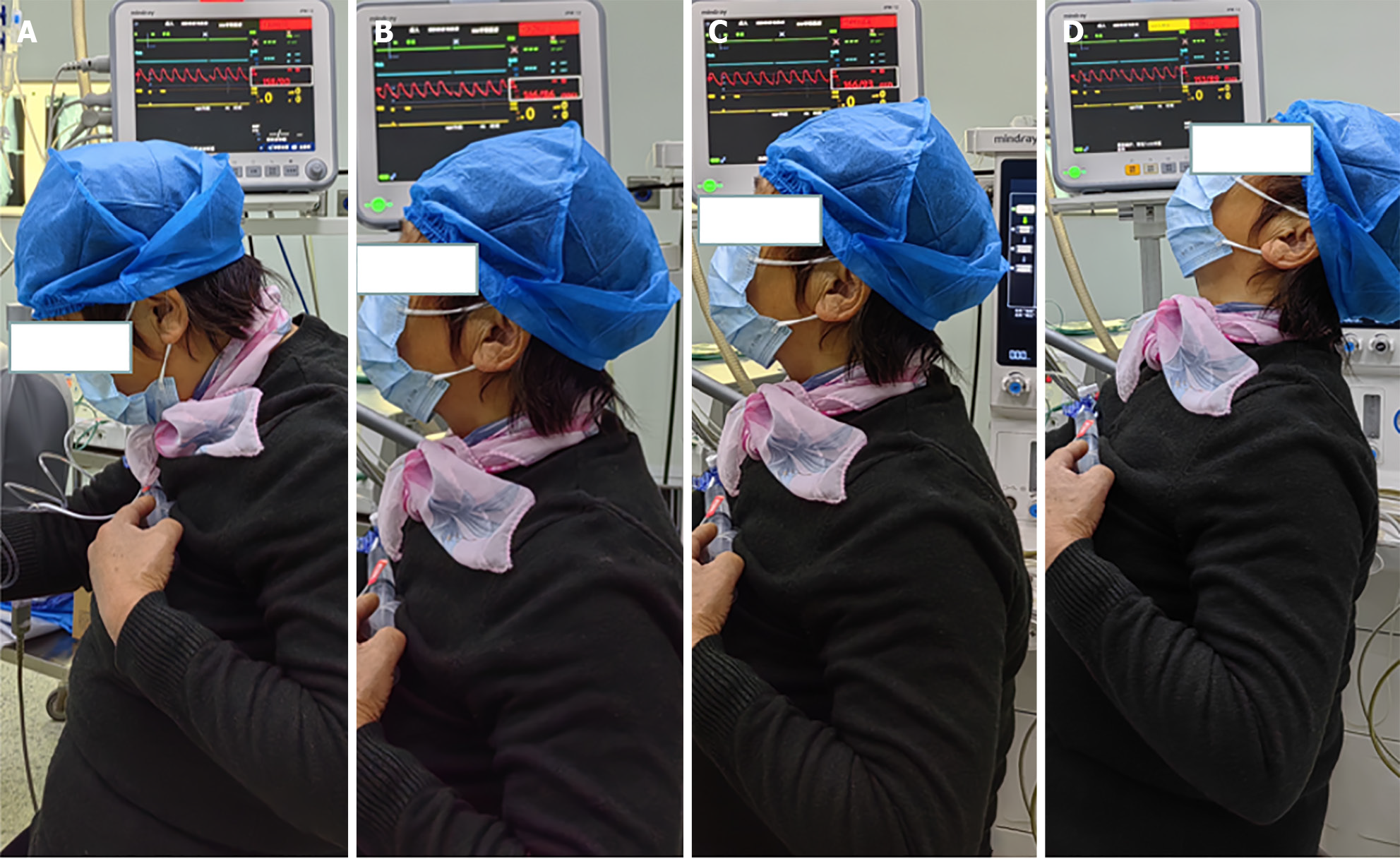

Figure 4 Six months post-surgery, ambulatory pulse blood pressure monitoring indicated systolic blood pressure fluctuations between 146–166 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure variations between 86–93 mmHg.

A: Cervical flexion, blood pressure at 158/90 mmHg; B: Neck in neutral position, blood pressure at 146/86 mmHg; C: Neck slightly extended: Blood pressure at 166/93 mmHg; D: Neck in complete extension, blood pressure at 153/89 mmHg.

DISCUSSION

Diagnosis of atypical CSR

CSR, the most common form of cervical spondylotic disease, occurs due to various pathologies including cervical disc degeneration, osseous hyperplasia, instability or dislocation of cervical articular ligaments, and cervical nerve root irritation or compression. Classic clinical manifestations of CSR are neck, shoulder, and back pain; radiating discomfort; numbness; and upper limb and finger weakness[5]. A subset of patients developed additional symptoms such as vertigo, headache, nausea, tinnitus, blurred vision, palpitations, memory loss, and gastrointestinal discomfort, collectively known as Barre-Lieou syndrome as it was initially described by Barre and Lieou in 1926[6]. Despite these symptoms being linked to degenerative cervical changes, current diagnostic modalities have been unable to identify radiological or pathological abnormalities responsible for these manifestations, thus rendering them atypical symptoms of cervical spondylosis[7]. Within the broader classification of cervical spondylotic diseases, this cervical spondylosis-associated atypical symptomatic presentation was termed sympathetic cervical spondylosis[8].

The diagnosis of atypical cervical spondylosis is controversial as definitive pathological mechanisms are unknown and specific diagnostic assays are lacking. Nevertheless, the diagnosis and treatment of atypical cervical spondylosis has garnered widespread acceptance in China's medical community[9] as well as by global scholars. A consensus has been reached that physical therapy and conservative manipulative treatment can mitigate cervical spondylosis-associated sympathetic nervous symptoms[10,11]. Machaly et al[12] identified a possible correlation between cervical spondylosis and occlusion of the vertebrobasilar artery during cervical rotation, which frequently leads to vertebrobasilar insufficiency and dizziness[12]. Sympathetic nervous symptoms were markedly alleviated in many patients with sympathetic cervical spondylosis after they underwent conventional anterior cervical decompression and fusion surgery[13]. While the etiology of cervical spondylosis-associated atypical symptoms remains elusive, clinical observations and intervention outcomes offer valuable diagnostic insights. Our patient's preoperative evaluation revealed no vertebral artery malformations or uncovertebral joint irregularities. Moreover, further diagnostic procedures eliminated the possibility of pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism. Although no reported instances of CSR concurrent with similar HEs are available, the patient's case qualifies as CSR presenting atypical symptoms, considering the predisposing factors for blood pressure elevation and complete resolution of symptoms after surgery.

Understanding the mechanism underlying CSR-induced HE

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for 2019 defined HEs as sudden and rapid increases in blood pressure that lead to regulatory abnormalities. Specifically, a systolic blood pressure of 220 mmHg or more and/or a diastolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more would indicate HE, irrespective of accompanying symptoms[2]. HEs are closely associated with high mortality and disability rates[14,15]. These emergencies are classified as malignant hypertension, rapidly progressive hypertension, and rapidly progressive malignant hypertension[16]. In the present case, despite successful administration of initial anesthesia, a minor extension of the patient's neck during postural positioning sharply elevated the blood pressure to 270/100 mmHg, thereby meeting the criteria for HE as per the ESC guidelines.

The relationship between cervical spondylosis and hypertension has been extensively investigated[17-19], with hypotheses being drawn for its mechanistic connection[20-25]. However, to our knowledge, no study has addressed the potential of cervical spondylosis to induce HEs. These events are often triggered by stress factors, such as activation of sympathetic hypertonia, and an increase in the release of vasoconstrictive substances, which can cause abrupt spikes in blood pressure[26]. Anatomically, the neck's sympathetic trunk lies behind the cervical vascular sheath, anterior to the cervical vertebrae’s transverse process. It typically has three sympathetic ganglia (superior, middle, and inferior) on each side, with the middle ganglion usually being the smallest and occasionally absent. The trunk is generally found at the C6 vertebra’s transverse process. The inferior ganglion is situated anterior to the root of the C7 vertebra’s transverse process, posterior to the start of the vertebral artery. It often fuses with the T1 ganglion to form the cervicothoracic ganglion, alias the stellate ganglion[27]. In our case, MRI unveiled a rupture of the C6/7 fibrous ring, and the herniated nucleus pulposus tissue compressing the C7 nerve root canal. This site coincides with the location of the middle or inferior cervical sympathetic ganglion. Existing evidence demonstrates the presence of segmentally distributed bidirectional neural connections between the cervical spinal and ipsilateral cervical sympathetic ganglia[28]. According to our hypothesis, the patient's neck hyperextension triggered further compression of the C6/7 intervertebral disc. This extra pressure directly affected the spinal ganglion at the posterior root of the right C7 spinal nerve by the prolapsed nucleus pulposus tissue on the right side. The spinal ganglion then stimulated the proximal cervical or subcortical sympathetic ganglion through bidirectional neural fibers, thus inducing the extensive activation of sympathetic hypertonia and release of vasoconstrictive substances. This cascade culminated in a HE (Figure 5).

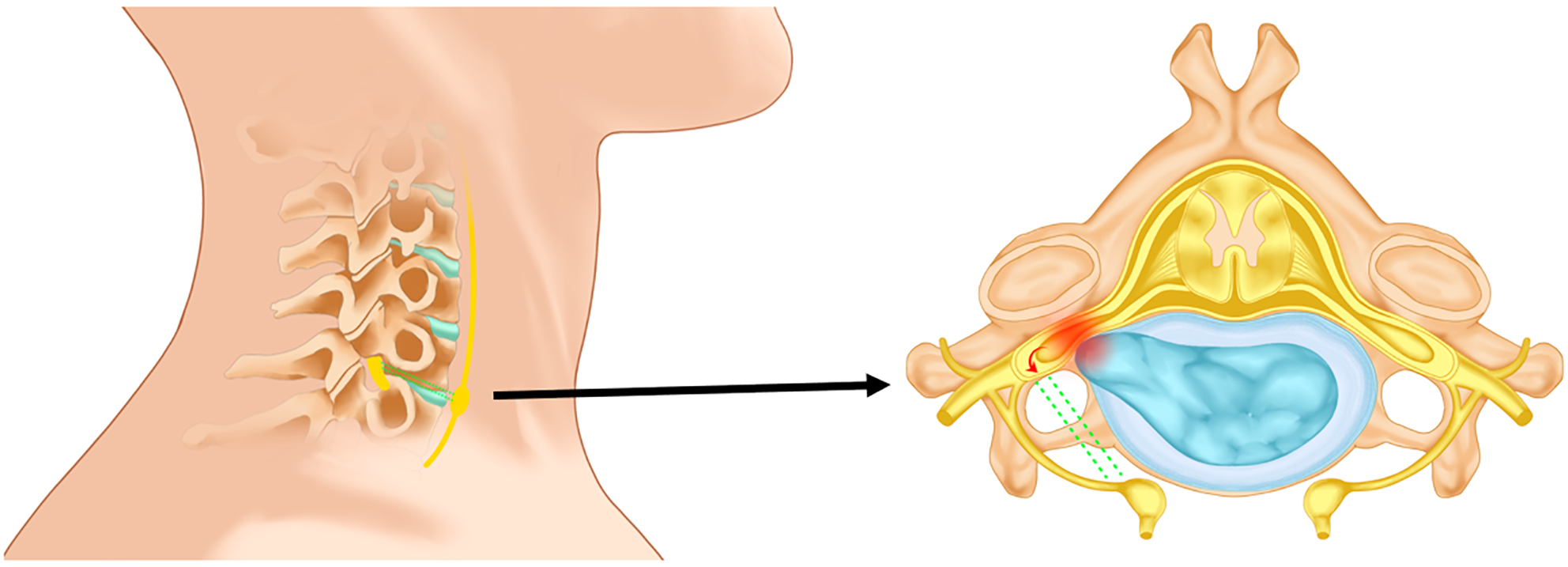

Figure 5 Overextension of the neck leads to further compression of the spinal ganglia by the nucleus pulposus tissue.

Following pressure stimulation, the spinal nerves directly excite the neck's sympathetic ganglia via bidirectional nerve fibers (represented by green dashed lines), thus activating the sympathetic nervous system and inducing a rapid blood pressure increase.

Application of posterior cervical canal expansion and foraminiscope-assisted transforaminal nucleus pulposus extraction

Notable symptom mitigation has been observed in patients exhibiting atypical symptoms of cervical spondylosis who underwent a double-door laminoplasty procedure[29]. In our patient, an anterior approach was deemed unsuitable because of the potential hypertensive crisis instigated by minimal neck extension. Consequently, posterior laminoplasty and foraminiscope-facilitated nucleus pulposus removal from the C6/7 right intervertebral foramen were performed. This combined surgical approach was selected based on the observed success of spinal canal decompression through single or double-door laminoplasty[30] and the efficacy of posterior laminoplasty for managing CSR[31]. Compared with the posterior cervical keyhole technique, the single-door method was less time-consuming, a notable factor for our patients vulnerable to unpredictable hypertensive crises. Additionally, the patient's reversed cervical arch contraindicated the keyhole procedure[32]. Nonetheless, posterior surgical approaches fail to excise the nucleus pulposus or pathological tissue situated ventrally and medially to the nerve root, a major disadvantage relative to anterior methods[33]. Because the patient's hypertensive crisis possibly stems from postural alterations compressing the herniated nucleus pulposus, thus stimulating the sympathetic nervous system, completely excising the ventrally located herniated nucleus pulposus is critical. This was achieved when the intervertebral foramen mirror's magnification and a matching hook needle were used to extract the protruding nucleus pulposus tissue after laminotomy.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the clinical findings of our case suggest that the right-sided herniated nucleus pulposus at the C6/7 vertebrae places pressure on the spinal ganglia at the posterior root of the right C7 vertebrae during cervical hyperextension. This induces direct excitation of the cervical sympathetic ganglia through bidirectional nerve fibers, which escalated sympathetic nervous system activity and prompted an acute, short-term elevation in blood pressure. For patients presenting with CSR concurrent with HEs, as in our case, adopting a cautious hypotensive posture and quickly performing comprehensive decompression surgery can proficiently alleviate the causative factors underpinning hypertensive crises safely. Additionally, it may be helpful to record blood pressure during different ranges of neck movement before surgery, which could potentially help identify potential cases of such atypical cervical spine disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the investigators and patient who contributed to this study.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A

Scientific Significance: Grade A

P-Reviewer: de Araújo Júnior FA S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG