Published online Apr 18, 2023. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v14.i4.260

Peer-review started: January 13, 2023

First decision: January 31, 2023

Revised: February 6, 2023

Accepted: March 23, 2023

Article in press: March 23, 2023

Published online: April 18, 2023

Processing time: 95 Days and 4.8 Hours

Tuberculosis remains a complicated problem. A lack of awareness accompanied by difficulty in diagnosis hinders the management of tuberculosis. Delayed management, particularly in osteoarticular regions, results in unnecessary procedures, including joint-sacrificing surgery.

Three cases of subclinical ankle joint tuberculosis without clear signs of tuber

The reports suggested that scintigraphy is recommended to diagnose subclinical tuberculous arthritis, especially in tuberculosis endemic regions.

Core Tip: Tuberculosis may present in a subclinical state that hindered the diagnosis and subsequent management. Technetium-99m-ethambutol scintigraphy is a useful noninvasive method to detect early stage of joint tuberculosis in which morphological and laboratory changes are still unclear. By using this method, earlier diagnosis and prompt intervention can be made especially in tuberculosis endemic regions, to avoid unnecessary procedures resulting from disease advancement.

- Citation: Primadhi RA, Kartamihardja AHS. Subclinical ankle joint tuberculous arthritis - The role of scintigraphy: A case series. World J Orthop 2023; 14(4): 260-267

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v14/i4/260.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v14.i4.260

Tuberculosis remains a currently public health problem worldwide, especially in developing countries. The resurgence of this disease, which began in the mid-1980s after a period of decreasing incidence, has been influenced by poverty, failures in the treatment system, immigration, and, unsurprisingly, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic[1,2]. Tuberculosis affects not only the lungs but also any other organs in the body, which is known as extrapulmonary tuberculosis, including osteoarticular sites. Tuberculosis of the foot and ankle is exceedingly rare, accounting for approximately one percent of all cases of osteoarticular tuberculosis[3-5].

The relative infrequency of foot and ankle tuberculosis may result in a lack of awareness among health care providers, and when combined with the similarity of tuberculosis symptoms with those of other diseases, diagnostic delays often occur[5]. The clinical features of this condition at early stages are nonspecific and may result in inadequate treatment and subsequent damage[4]. Subclinical tuberculosis occurs in asymptomatic, immunocompromised hosts, with loss of effective containment. Therefore, subclinical tuberculosis rapidly progresses if left untreated[6].

The final diagnosis of tuberculosis can be made by histopathological testing and/or microorganism culture. However, these methods are hindered by their long processing time and the difficulty of obtaining adequate specimen tissues. Nuclear medicine modalities, particularly Technetium-99m-Ethambutol scintigraphy, are quick and effective methods to diagnose tuberculosis even at an early stage of the disease[3,7].

This report describes three cases of subclinical ankle joint tuberculosis with diagnostic difficulty that were subsequently diagnosed by scintigraphy. All scintigraphy procedures were carried out in the Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia. Informed consent for publications was obtained from all patients or family. This case series was recognized and approved by Hasan Sadikin Hospital Institutional Review Board No. LB.02.01/X.6.5/250/2022.

All patients presented a slight pain and swelling on their ankle joints for several months.

Case 1: A 17-year-old female presented with slight pain and swelling of the bilateral ankle. The complaint slowly worsened, starting four months prior to the hospital visit. There was no history of injury near the ankle, swelling in any other body regions, fever, chills, or unexpected weight loss. She had taken analgesics for one month, but the pain and swelling remained.

Case 2: A 22-year-old female was referred to our foot and clinic for a chronic ankle sprain resulting from a low-energy trauma. Initial treatment from a previous hospital included immobilization with a semirigid cast for three weeks followed by protective partial weight bearing, along with anti-inflammatory analgesics. After six weeks, she still complained of pain, swelling, and limited motion.

Case 3: A 36-year-old female presented with slight pain and a swollen right ankle that had lasted for two months. There was no history of injury near the ankle, swelling in any other body regions, fever, chills, or unexpected weight loss. She had been given anti-inflammatory analgesics, but the pain and swelling persisted.

No relevant history of past illness was found in Case 1 and 2. However, Case 3 present a pulmonary tuberculosis that might be related to current symptoms.

No relevant personal and family history was found in all cases.

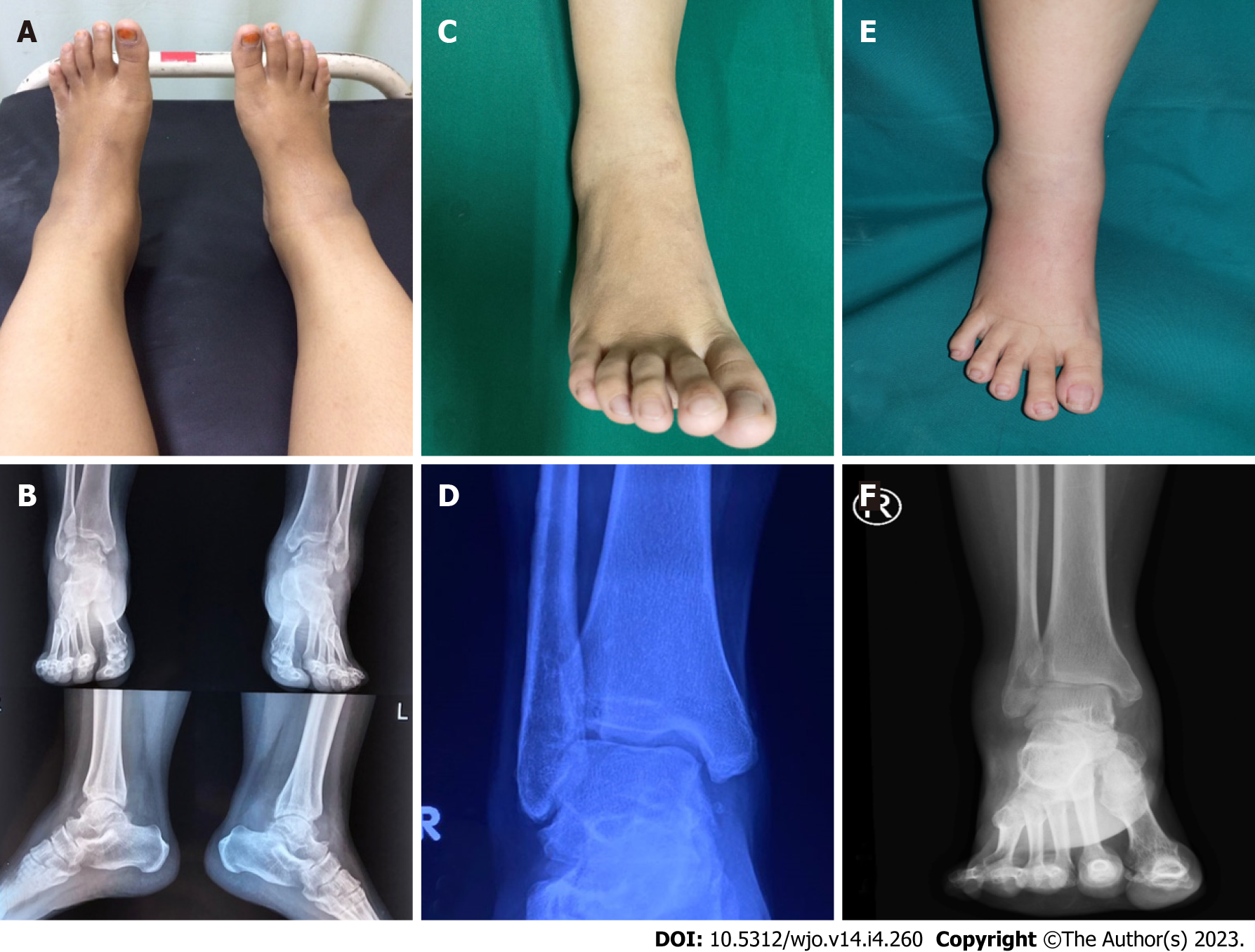

Case 1: The patient appeared healthy based on general appearance. Upon physical examination, slight swelling was observed by inspection and palpation (Figure 1A). Pain was induced by direct pressure and joint motion, especially ankle dorsiflexion.

Case 2: The patient presented at the clinic using crutches due to difficulty and pain while walking. Swelling was visible on the whole ankle, including the lateral and medial sides (Figure 1C). Pain was induced with palpation and ankle joint movement.

Case 3: She was undergoing pulmonary tuberculosis treatment and had been administered anti-tuberculosis therapy for four months. On physical examination, slight swelling was observed in the ankle region by inspection and palpation (Figure 1E). She was still able to walk normally.

Case 1: Laboratory blood tests showed normal values, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 8.6 × 109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 9 mm/h, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 3 mg/L. Other biochemical parameters were within the normal range, and chest radiography was unremarkable.

Case 2: The WBC count was 11.0 × 109/L, ESR was 20 mm/h, and the CRP level was 4.9 mg/L. Other laboratory results were within normal reference values.

Case 3: Laboratory blood tests showed a WBC count of 10.4 × 109/L, ESR of 25 mm/h, and CRP level of 7.4 mg/L. Other biochemical parameters were within the normal range.

Case 1: Plain ankle radiography was inconclusive, showing no localized bony lesion, osteoporosis, or articular changes (Figure 1B).

Case 2: Ankle radiography showed soft tissue swelling without remarkable bony derangement (Figure 1D).

Case 3: Narrowing joint space was observed on plain ankle radiography (Figure 1F).

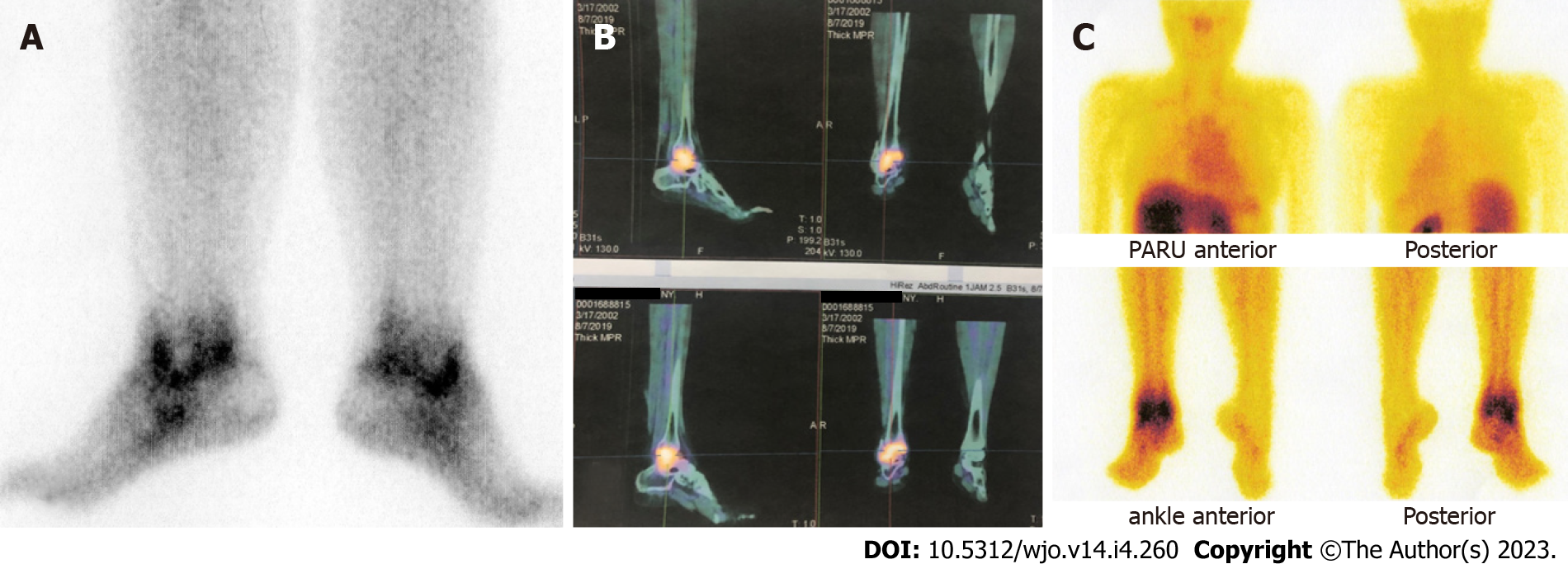

Referring to positive scintigraphy results (Figure 2), all patients were diagnosed as tuberculous arthritis of ankle joint.

All patients were subsequently given anti-tuberculosis therapy according to extrapulmonary tuberculosis treatment protocol.

After the completion of therapy, the symptoms had improved, and she returned to normal daily activities.

The symptoms improved afterward, although the patient still needed physical therapy due to ankle arthrofibrosis.

After the completion of therapy, the symptoms improved, although the swelling did not completely resolve.

Subclinical tuberculosis disease is difficult to identify. It may be entirely asymptomatic or may present subtle symptoms that are underreported according to classic tuberculosis symptom screenings. Tuberculous arthritis shows wide variability in clinical symptoms and imaging appearance, ranging from asymptomatic with normal radiographic examination to severe joint pain along with joint destruction. Its slow progression and chronicity cause patients to present with subtle symptoms and signs, resulting in delayed diagnosis. The identification of people who have asymptomatic tuberculosis is a diagnostic challenge[8,9]. From a public health perspective, the concern is whether these people are infectious or not[10]. The significance from an osteoarticular problem standpoint is that timely intervention will help avoid the sequelae of joint destruction and disability that require joint-sacrificing surgical procedures, such as ankle fusion or arthroplasty.

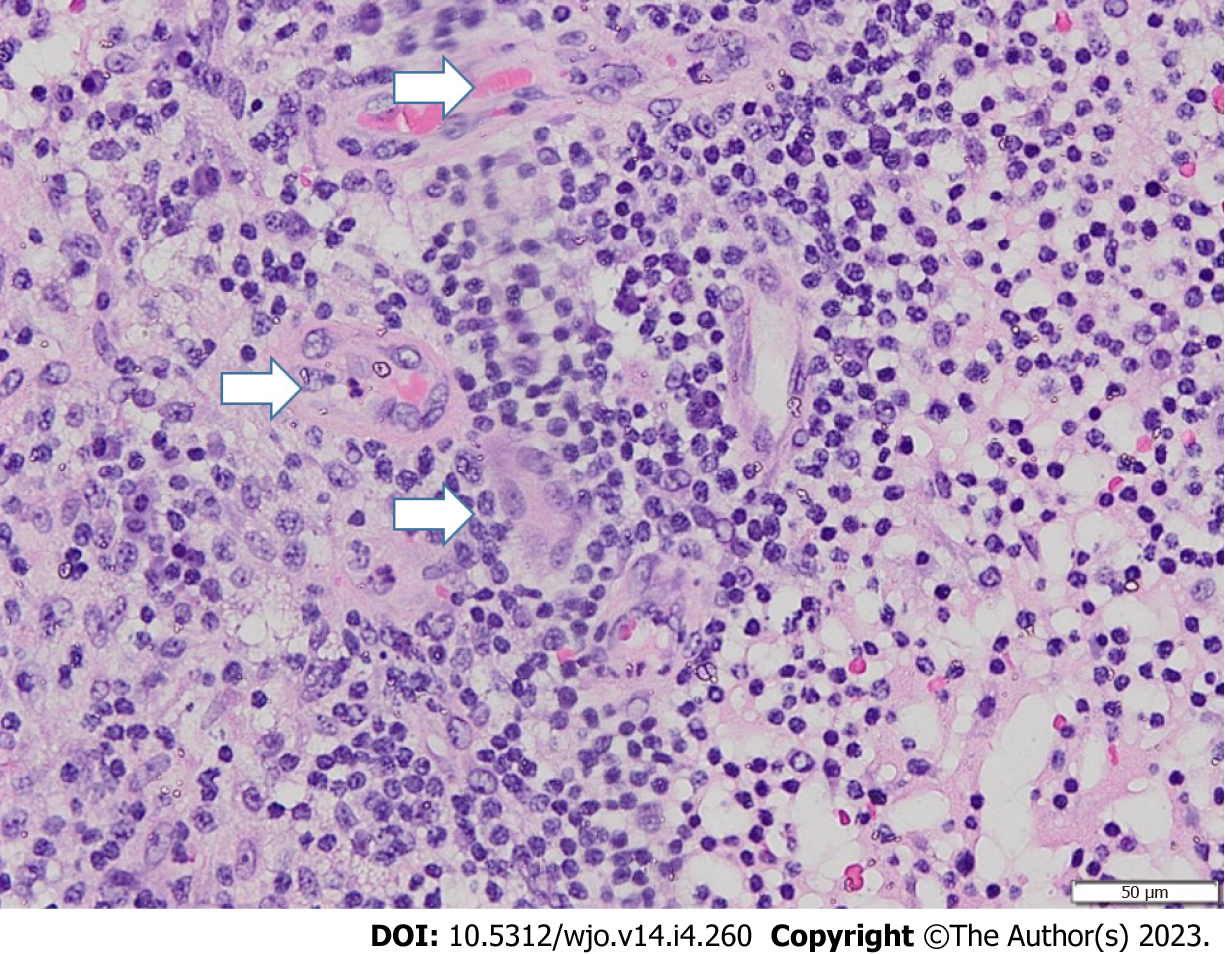

Clinical features of tuberculosis are nonspecific and may overlap with other conditions, including pyogenic osteomyelitis or arthritis, bone tumors, pigmented villonodular synovitis, avascular necrosis of the talus, and other inflammatory processes[4,11]. However, the diagnosis of mycobacterial arthritis should be entertained when chronic monoarticular arthritis is encountered. The Phemister triad is an eponym that refers to three classic radiological features seen in tuberculous arthropathy: (1) Juxta-articular osteoporosis; (2) peripheral osseous erosions; and (3) gradual narrowing of joint spaces (Figure 3)[12]. A flaky sequestrum in a cavity and/or dystrophic calcification in soft tissue are suggestive of tuberculous pathologies[5]. Specialized investigations, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging, may be helpful to assess signals, synovial proliferation, and bone marrow edema. However, radiological findings are still often inconclusive and lack specific findings, especially at an early stage. By the time bony destruction appears, the tuberculosis disease process is severe and capable of contiguous or hematological spread to the sites[13]. Confirmatory tests included the isolation of acid-fast bacilli on specialized culture media and histopathological findings depicting a chronic granulomatous inflammatory process with multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). A positive Mantoux tuberculin skin test can be obtained in patients with long-standing tuberculosis but is also considered not specific since it can also be obtained in vaccinated populations and in people in endemic areas[5].

Some inflammatory markers, such as those measured in laboratory blood tests, reflect the activity of tuberculosis. In tuberculosis patients, the serum hemoglobin level, red blood cell count, and platelet count are decreased, whereas ESR, CRP, and WBC are increased compared with controls[14]. ESR is an inflammatory marker and reflects the sedimentation of erythrocytes after a period of 60 min. In the acute inflammatory phase, increased serum proteins neutralize red blood cells, resulting in stacking aggregation and subsequent increased ESR[15]. A prior study reported that although an elevated ESR may be expected in tuberculosis patients, one-third of children had a normal ESR at the time of diagnosis[16]. CRP is considered a favorable tool for active tuberculosis screening[17]. CRP is an acute-phase reactant protein that is primarily induced by IL-6 during the acute phase of an inflammatory/infectious process[18]. There are numerous causes for elevated CRP, including acute or nonacute and infectious or noninfectious. Trauma can also cause CRP elevation. However, it is most often associated with infection. The WBC count is increased during infection due to the body’s immune defense mechanism that combats invading bacteria, in which the numbers of polymorphonuclear and macrophage cells increase[14]. In these reported cases, all patients’ WBC, ESR, and CRP data were within the normal range. Considering the inconsistency of laboratory results for tuberculosis diagnosis, adjunct examination is still needed to establish the diagnosis.

Nuclear medicine scintigraphy is known as a noninvasive diagnostic modality with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting and locating the lesion at an early stage. The metabolic activity of the skeleton can be visualized by bone scan. Nuclear scintigraphy of the bone commonly utilizes the radionuclides technetium-99m or fluoride-18. These molecules are intravenously injected, and then a dual-head SPECT-CT gamma camera is used to capture the decay of photons from the radioisotope at the suspected site[3,19]. Ethambutol is an active specific antibiotic against mycobacterium. Technetium-99m-labeled ethambutol is specifically taken up by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and detected under a gamma camera at 1 h and 3 h after the intravenous injection of 370-740 MBq. Technetium-99m-ethambutol remains in tubercular lesions as it is bound to mycolic acid in the cell wall of bacteria but is cleared from nontubercular lesions[7]. The image interpretation was as follows: (1) Normal scan, if there was no pathologically increased uptake other than the normal uptake in the kidney, urinary bladder, liver, and spleen; (2) positive scan, if pathological uptake was observed at the suspected site and gradually increased with time; and (3) negative scan, if pathological uptake was observed at 1 h and gradually decreased (washed out) at the 3-h image[3]. Negative scan implies that the tuberculosis infection is not established, as the strong bond between technetium-99m-ethambuthol and the mycobacteria is not formed. Other radiopharmaceutical agents have also been introduced, such as ciprofloxacin and isoniazid. Technetium-99m-ciprofloxacin can be useful for bacterial infection imaging but cannot differentiate tuberculosis from other bacterial infections, as it acts as a broad-spectrum antibiotic that can be taken up by any living bacteria. Technetium-99m-isoniazid has also been developed but is not widely used clinically[7,20]. This method results in only minimal or no side effects, since the dosage of radiotracer given to the patient is only 2 mg and excreted through the physiological process[3].

The basic principles of tuberculosis control include early detection and well-timed management of the affected patients. There was a clear association between delay of treatment and clinical severity at presentation due to the longer time for disease progression[21]. In general, in septic arthritis, when the infection is not cleared quickly, the potent activation of the immune response with the associated high levels of cytokines and reactive oxygen species leads to joint destruction through glycosaminoglycan loss[22]. The infection process also promotes joint effusion that increases intra-articular pressure, mechanically hindering blood and nutrient supply to the joint and causing damage to the synovium and cartilage[22]. In tuberculous arthritis, cartilaginous tissue is more resistant to destruction. However, penetration of the epiphyseal cartilage plate occurs more often in tuberculous disease than in pyogenic infection . In these cases, anti-tuberculosis drugs were directly given to the patients after a positive scan. All patients had received systemic antituberculosis drugs under an extrapulmonary tuberculosis treatment protocol consisting of two months of combined rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, followed by ten months of rifampin and isoniazide. This treatment approach was in line with a prior report that allowed the anti-tuberculosis regimen to proceed to the histopathological examination first[3]. In our institution, technetium-99m-ethambutol scintigraphy has been chosen for many orthopedic cases with tuberculosis suggestion. Kartamihardja et al[7] had reported that as much as 78% subjects with tuberculosis infection were positive on both technetium-99m-ethambutol scintigraphy and microbiological/histopathological findings, and 14.9% subjects presented negative results on both examinations, yielding more than 90% specificity. However, there are still 12 (7.1%) discordant results between examinations[7].

This report showed that technetium-99m-ethambutol scintigraphy is simple and effective for detecting subclinical tuberculosis in the ankle joint. Patients with a positive result could be directly treated with anti-tuberculosis drugs. The advantages of this method include the rapid results, noninvasive features, ability to detect disease in early stages, and avoidance of the risk of inadequate tissue specimens. The use of this method for diagnosing such cases should be advocated, especially in tuberculosis endemic regions, to avoid treatment delays.

| 1. | Glynn JR. Resurgence of tuberculosis and the impact of HIV infection. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:579-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pealing L, Moore D, Zenner D. The resurgence of tuberculosis and the implications for primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:344-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Diah LH, Kartamihardja AHS. The role of Technetium-99m-Ethambutol scintigraphy in the management of spinal tuberculosis. World J Nucl Med. 2019;18:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choi WJ, Han SH, Joo JH, Kim BS, Lee JW. Diagnostic dilemma of tuberculosis in the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:711-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dhillon MS, Tuli SM. Osteoarticular tuberculosis of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Achkar JM, Jenny-Avital ER. Incipient and subclinical tuberculosis: defining early disease states in the context of host immune response. J Infect Dis. 2011;204 Suppl 4:S1179-S1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kartamihardja AHS, Kurniawati Y, Gunawan R. Diagnostic value of (99m)Tc-ethambutol scintigraphy in tuberculosis: compared to microbiological and histopathological tests. Ann Nucl Med. 2018;32:60-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hong SH, Kim SM, Ahn JM, Chung HW, Shin MJ, Kang HS. Tuberculous versus pyogenic arthritis: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 2001;218:848-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prasetyo M, Adistana IM, Setiawan SI. Tuberculous septic arthritis of the hip with large abscess formation mimicking soft tissue tumors: A case report. Heliyon. 2021;7:e06815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wong EB. It Is Time to Focus on Asymptomatic Tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e1044-e1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hanène F, Nacef L, Maatallah K, Triki W, Kaffel D, Hamdi W. Tuberculosis arthritis of the ankle mimicking a talar osteochondritis. Foot (Edinb). 2021;49:101816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chattopadhyay A, Sharma A, Gupta K, Jain S. The Phemister triad. Lancet. 2018;391:e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Korim M, Patel R, Allen P, Mangwani J. Foot and ankle tuberculosis: case series and literature review. Foot (Edinb). 2014;24:176-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rohini K, Surekha Bhat M, Srikumar PS, Mahesh Kumar A. Assessment of Hematological Parameters in Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2016;31:332-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alende-Castro V, Alonso-Sampedro M, Vazquez-Temprano N, Tuñez C, Rey D, García-Iglesias C, Sopeña B, Gude F, Gonzalez-Quintela A. Factors influencing erythrocyte sedimentation rate in adults: New evidence for an old test. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Al-Marri MR, Kirkpatrick MB. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate in childhood tuberculosis: is it still worthwhile? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:237-239. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yoon C, Chaisson LH, Patel SM, Allen IE, Drain PK, Wilson D, Cattamanchi A. Diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein for active pulmonary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:1013-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vanderschueren S, Deeren D, Knockaert DC, Bobbaers H, Bossuyt X, Peetermans W. Extremely elevated C-reactive protein. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:430-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brenner AI, Koshy J, Morey J, Lin C, DiPoce J. The bone scan. Semin Nucl Med. 2012;42:11-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee M, Yoon M, Hwang KH, Choe W. Tc-99m Ciprofloxacin SPECT of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;44:116-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Virenfeldt J, Rudolf F, Camara C, Furtado A, Gomes V, Aaby P, Petersen E, Wejse C. Treatment delay affects clinical severity of tuberculosis: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shirtliff ME, Mader JT. Acute septic arthritis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:527-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang X, China; Rothschild B, United States S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY