Published online Apr 18, 2022. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v13.i4.381

Peer-review started: May 17, 2021

First decision: July 6, 2021

Revised: July 29, 2021

Accepted: March 4, 2022

Article in press: March 4, 2022

Published online: April 18, 2022

Processing time: 329 Days and 13.2 Hours

Iliopsoas muscle abscess (IPA) and spondylodiscitis are two clinical conditions often related to atypical presentation and challenging management. They are both frequently related to underlying conditions, such as immunosuppression, and in many cases they are combined. IPA can be primary due to the hematogenous spread of a microorganism to the muscle or secondary from a direct expansion of an inflammatory process, including spondylodiscitis. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous drainage has been established in the current management of this condition.

To present a retrospective analysis of a series of 8 immunocompromised patients suffering from spondylodiscitis complicated with IPA and treated with percutaneous computed tomography-guided drainage and drain insertion in an outpatient setting.

Patient demographics, clinical presentation, underlying conditions, isolated microorganisms, antibiotic regimes used, abscess size, days until the withdrawal of the catheter, and final treatment outcomes were recorded and analyzed.

All patients presented with night back pain and local stiffness with no fever. The laboratory tests revealed elevated inflammatory markers. Radiological findings of spondylodiscitis with unilateral or bilateral IPA were present in all cases. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in 3 patients and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 2 patients. Negative cultures were found in the remaining 3 patients. The treatment protocol included percutaneous computed tomography-guided abscess drainage and drain insertion along with a course of targeted or empiric antibiotic therapy. All procedures were done in an outpatient setting with no need for patient hospitalization.

The minimally invasive outpatient management of IPA is a safe and effective approach with a high success rate and low morbidity.

Core Tip: Eight patients diagnosed with spondylodiscitis complicated with iliopsoas muscle abscess were managed with minimally invasive percutaneous computed tomography-guided drainage, placement of a drain, and proper antibiotic treatment in an outpatient setting. Complete recession of the symptoms with no recurrence after 6 mo was observed. The minimally invasive outpatient management of iliopsoas muscle abscess is a safe and effective approach with a high success rate and low morbidity.

- Citation: Fesatidou V, Petsatodis E, Kitridis D, Givissis P, Samoladas E. Minimally invasive outpatient management of iliopsoas muscle abscess in complicated spondylodiscitis. World J Orthop 2022; 13(4): 381-387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v13/i4/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v13.i4.381

Iliopsoas muscle abscess (IPA) is a rare infective clinical condition often related to nonspecific symptoms and a variety of etiologies[1]. It was first described by Mynter in 1881 and was characterized as “acute psoitis”[2]. Two proposed mechanisms lead to IPA. Primary IPAs are caused by a hematogenous spread of an infective microorganism that leads to IPA formation due to the muscle’s rich vascularity, especially in immunocompromised patients. Secondary IPAs are developed by a contiguous spread of an intra-abdominal inflammatory process or by musculoskeletal conditions such as spondylodiscitis, sacroiliitis, or tuberculosis of the spine[1,3,4].

Spondylodiscitis is the most common form of spinal infection, affecting the intervertebral disc and the adjacent vertebral bodies and can present isolated or combined with other underlying conditions such as infections, malignancy, and immunosuppression[5]. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis can result in IPA due to direct expansion into the iliopsoas.

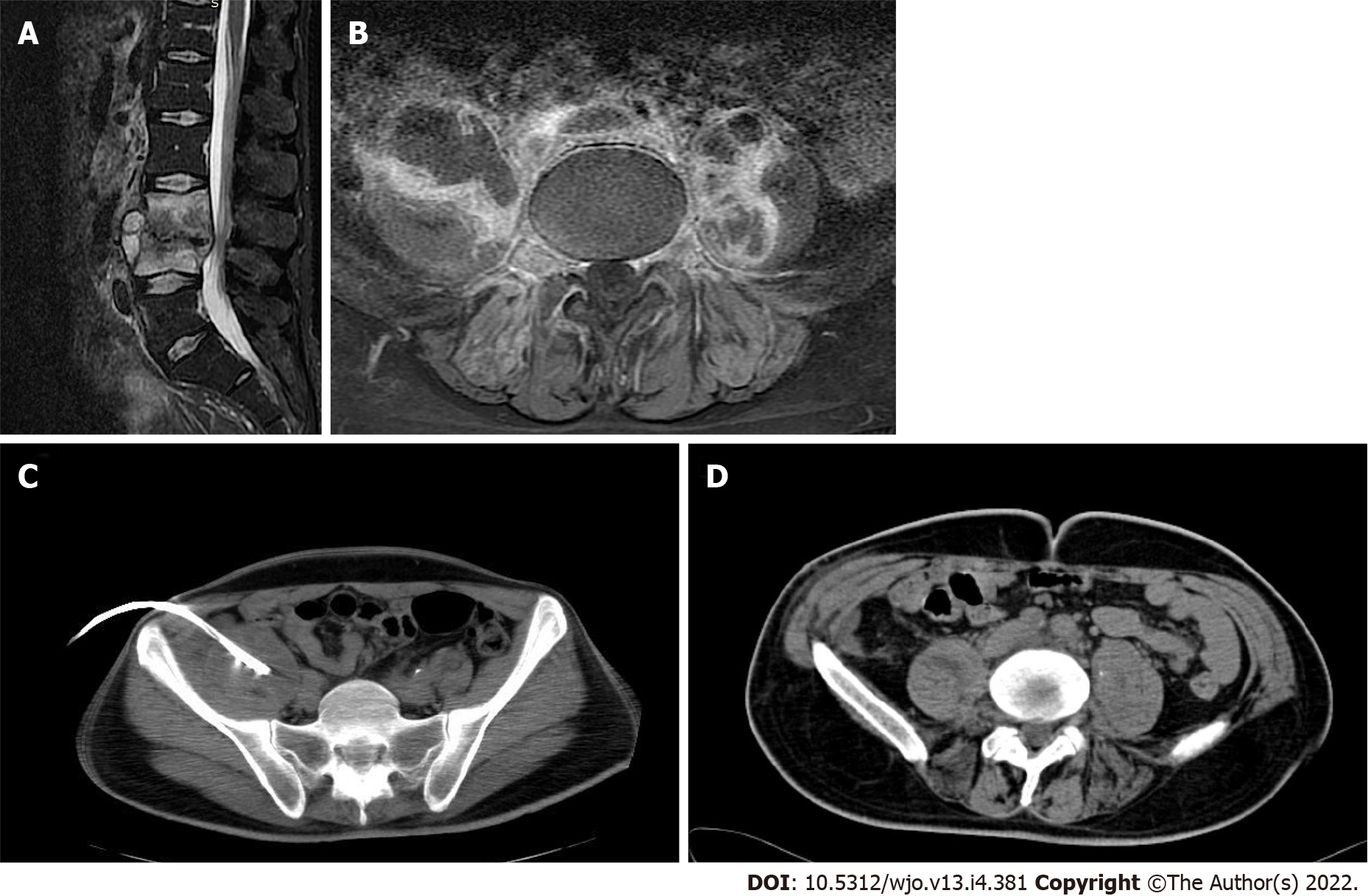

Symptoms of IPA may be insidious and nonspecific due to the location of the iliopsoas muscle, but the classical clinical presentation described in the literature includes the triad of fever, back pain, and limp[6,7]. Due to the atypical clinical features, diagnosis is oftentimes delayed leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Once an IPA is suspected, computed tomography (CT) scan is recommended, with a high sensitivity rate approaching 100%, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine is the most indicative imaging for spondylodiscitis[4,8]. There is no uniform treatment strategy for IPA. Traditionally, surgical drainage of the abscess along with a broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment was the preferred treatment[1,9,10]. However, more recent literature reports that the percutaneous CT-guided abscess drainage is a safe and equally effective alternative[1,8,11]. The purpose of the current study was to present and evaluate a case series of 8 patients diagnosed with spondylodiscitis complicated with IPA. The patients were managed with antimicrobial therapy, minimally invasive percutaneous CT-guided drainage, and the addition of a short-term drain insertion in an outpatient setting.

A retrospective collection and analysis of all radiologically diagnosed cases of IPA that were treated with CT-guided percutaneous drainage from 2016 to 2020 in the department of Interventional Radiology of a tertiary University hospital was performed. All cases initially presented to the spinal outpatient clinic complaining of back pain and were diagnosed with spondylodiscitis and IPA formation after an MRI and a CT scan. Records were extracted from the Interventional Radiology department’s database. Data were reviewed for patient demographics, underlying conditions, isolated microorganisms, antibiotic regimes used, abscess size, days until the withdrawal of the catheter, and final outcome.

All abscesses were defined as secondary IPAs due to the concurrent presence of spondylodiscitis. Two patients were diagnosed specifically with tuberculosis of the spine. There was no neurological compromise, spinal instability, or bone deformity present due to spondylodiscitis.

Treatment success was marked by clinical and laboratory improvement along with radiological confirmation of recession of the abscess and eventually catheter removal. All patients were clinically evaluated 6 mo after the end of their treatment.

All draining procedures were performed by direct insertion of a 12 Fr pigtail catheter into the abscess cavity. Before the procedure, a CT and MRI scan were performed. Values of international normalized ratio less than 1.5 and platelet count greater than 50000/μL were required to proceed with the drainage, and antiplatelet or anticoagulation medication had to be discontinued accordingly. Patients were placed in the prone position in most cases (7 out of 8 patients). The placement decision was made depending on the best approach to the abscess cavity. All procedures were performed under local anesthesia and aseptic conditions. After an initial CT scan for approach planning, the trocar pigtail catheter was advanced into the abscess cavity under CT guidance. When the trocar reached the middle of the fluid collection it was withdrawn while the catheter was advanced and secured in position (Figure 1). Manual aspiration of the fluid was then performed, and the catheter was connected to a drainage bag. The inserted drain was removed if there was no drainage for 48 h.

A total of 8 patients that underwent CT-guided percutaneous IPA drainage were included in the study (Table 1). Their mean age was 52.6 ± 20.8-years-old, and there were six unilateral and two bilateral cases, a total of 10 abscesses. All cases were secondary; six were in immunocompromised patients [renal failure, HIV, intravenous (IV) drugs] with spondylodiscitis and two were in patients diagnosed with tuberculosis of the spine.

| Patient | Sex | Age in yr | Underlying condition | Site | Position | Size in cm | Procedure time in min | Presenting complaint | Catheter withdrawal in d | Microbiologic cultures |

| 1 | Male | 76 | Renal failure- dialysis | Unilateral | Prone | 4.5 | 15 | Back pain | 8 | Negative |

| 2 | Female | 69 | Renal failure- dialysis | Unilateral | Prone | 6.4 | 15 | Back pain, weight loss | 10 | Negative |

| 3 | Male | 74 | Renal failure- dialysis | Bilateral | Prone | 7.5/4.5 | 25 | Back pain | 8 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 4 | Female | 68 | Renal failure- dialysis | Unilateral | Prone | 4.4 | 10 | Back pain | 9 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 5 | Female | 34 | HIV | Bilateral | Prone | 5.5/4.3 | 25 | Back pain | 8 | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 6 | Male | 35 | IV drug user | Unilateral | Supine | 8.3 | 10 | Back pain | 13 | Negative |

| 7 | Male | 38 | Tuberculosis | Unilateral | Prone | 7.5 | 15 | Back pain | 11 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| 8 | Female | 27 | Tuberculosis | Unilateral | Prone | 10.4 | 15 | Back pain | 14 | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

All patients presented at the spine outpatient clinic complaining of back pain for at least 3 mo with worsening at night, and 1 patient also mentioned weight loss. At clinical examination, there was local sensitivity and palpable muscle spasm found in all patients with no neurological compromise. All patients remained afebrile. From the laboratory investigation, there was an increase in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate).

The diagnosis was confirmed by MRI followed by CT. According to imaging calculations, the mean abscess size was 6.3 ± 2.1 cm. There was no bone deformity or spinal degeneration observed. The drainage procedure was arranged immediately and performed in the next 1-3 d from the initial diagnosis. A 12 Fr pigtail drain was inserted in all cases, as previously described. The average time until the withdrawal of the catheter was 10 ± 2 d.

Microbiology samples from the abscess fluid were sent in all cases. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in 3 cases, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was isolated in 2 patients, and there was no specific microorganism isolated in 2 renal impairment/dialysis patients and 1 IV drug user. All patients initially received empiric antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin and clindamycin orally. After the culture results, patients with Staphylococcus aureus culture isolation received a targeted 2-wk course of intravenous vancomycin and oral rifampicin with daily outpatient visits, followed by oral linezolid and rifampicin for another 6 wk. The tuberculosis patients underwent a 9-mo antimicrobial treatment with oral isoniazid, ethambutol, and rifampicin, whereas the patients with no specific microorganism isolated received an 8-wk empiric antibiotic treatment as presented in Table 2. All abscesses were successfully drained on the first attempt, and all patients had a complete resolution of symptoms. There were no recurrences at the 6-mo follow-up.

| Microorganism | n | Antibiotic treatment | Duration |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 | Rifampicin PO - Vancomycin IV | 2 wk |

| Rifampicin PO - Linezolid PO | 6 wk | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 2 | Rifampicin PO - Isoniazid PO - Ethambutol PO | 9 mo |

| Negative cultures, renal impairment patients | 2 | Vancomycin IV - Ciprofloxacin PO | 8 wk |

| Negative cultures, IV drug user | 1 | Ciprofloxacin PO - Clindamycin PO | 4 wk |

| Ciprofloxacin PO - Rifampicin PO | 3 wk |

We present a case series of 8 patients suffering from spondylodiscitis complicated with IPA, successfully treated with a minimally invasive approach of combined percutaneous abscess drainage with drain insertion and antibiotic therapy. Immunosuppression is the predominant underlying condition in IPA and may be responsible for the insidious presenting signs and symptoms[9]. In the current series, there was a higher prevalence of IPA in patients that were on renal dialysis, immunocompromised by HIV, or IV drug users. Moreover, tuberculosis is linked to secondary IPA due to vertebral involvement[11-13]. Although tuberculosis is rare, there were 2 cases of secondary IPA in patients with tuberculosis of the spine.

The clinical triad of IPA symptoms as described by Mynter[2] in 1881 includes back pain, limping, and fever. Subsequent studies have identified more nonspecific symptoms such as weight loss, lower extremity pain, lower extremity edema, gastrointestinal symptoms, and a palpable mass[8]. The laboratory findings include elevated white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate as well as anemia[3,4]. In the present case series, none of the patients presented with the typical IPA symptomatology. The patients’ underlying conditions along with the raised inflammatory markers guided the physicians to suspect an inflammatory condition of the spine.

The final diagnosis of IPA is confirmed by the imaging findings. Several studies recommend ultrasound as the initial radiological investigation. However, it is an operator-dependent procedure with a low diagnostic rate[1,9,14]. CT scan is considered to be the “gold standard” for a definitive diagnosis of IPA, and MRI adds more detailed imaging of the abscess wall, the soft tissues, and the surrounding structures without the need for IV contrast infusion[3,15-17]. Both MRI and CT scans were performed in the current study and revealed signs of spondylodiscitis with unilateral or bilateral IPA formation in all patients. Although IPA is mainly described as an outcome of spondylodiscitis[7], literature also describes spondylodiscitis as a complication of an established IPA[18]. Therefore, it could not be clearly stated which condition was presented first. Spondylodiscitis, however, did not require invasive treatment in contrast to the IPA formation.

The literature traditionally suggests early surgical management of the IPA, which suggests a long in-hospital stay. The surgical procedure of choice, according to Ricci et al[9] in 1986, was abscess drainage through a lower abdominal muscle-splitting, extraperitoneal incision. In more recent years, with the evolution of interventional radiology, minimally invasive percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses, including IPA, is the treatment method of choice[11]. This approach is preferred especially for immunocompromised patients, as it eliminates the need for general anesthesia and is also associated with a shorter hospital stay, minimizing morbidity and mortality. There is currently no literature describing the management of such patients with a drain insertion in an outpatient setting. In the current series, all patients were managed as outpatients. All patients underwent CT-guided drainage and drain insertion without delay from the time of diagnosis. The drain insertion increased the success rate of the drainage, and no repeat procedures were necessary.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should cover against Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative and gram-positive microorganisms, including bowel flora and common urinary tract infection bacteria, and targeted therapy should be commenced immediately after the culture results[14]. For mycobacterial infections, a 9-mo conventional antituberculosis therapy was applied. For non-mycobacterial infections, as all cases presented with vertebral involvement, the minimum duration of the antibiotic treatment was 8 wk, including at least 2 wk of IV vancomycin, and prolonged according to laboratory and radiological findings. Those receiving IV vancomycin visited the outpatient clinic daily for the first 2 wk for the infusions.

The drain catheter remained in place until no drainage was observed for 2 consecutive days. A follow-up CT scan was performed between days 7 and 14 to confirm abscess recession.

The current study has several limitations. First, it is a single-center study of a small pilot patient group, which reflects the rarity of the condition. Second, no control group was recruited. Moreover, the retrospective study design might introduce recall or patient selection bias.

The minimally invasive outpatient management of IPA is a safe and effective approach with a high success rate and low morbidity.

There has been an evolution in the management of complicated spondylodiscitis with iliopsoas muscle abscess (IPA) formation through the years and computed tomography (CT)-guided drain insertion with antibiotic therapy being the current practice.

Complicated spondylodiscitis with IPA formation in immunocompromised patients could be managed in an outpatient setting.

The purpose of the current study was to describe the care management of complicated spondylodiscitis.

A 4-year retrospective collection and analysis of all radiologically diagnosed cases of IPA that were treated with CT-guided percutaneous drainage. Data included patient demographics, underlying conditions, isolated microorganisms, antibiotic regimes used, abscess size, days until the withdrawal of the catheter, and final outcome. All draining procedures were performed by direct insertion of a 12 Fr pigtail catheter into the abscess cavity.

All 8 patients were diagnosed with IPA formation secondary to complicated spondylodiscitis, and two of them were diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis. All 8 patients showed complete recession of the symptoms and radiological findings after the CT-guided abscess drainage and the long-term antibiotic therapy. The microbiology cultures identified Staphylococcus aureus in 3 cases and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 2 cases and were negative in the remaining 3 cases. There was no need for patient hospitalization.

The minimally invasive outpatient management of IPA, which combines CT-guided percutaneous drainage and placement of a drain with proper antibiotic treatment, proved to be a safe and effective approach with a high success rate and low morbidity.

More studies should be performed in order to prove the cost effectiveness and the decreased morbidity of the minimally invasive outpatient management of these patients.

| 1. | Shields D, Robinson P, Crowley TP. Iliopsoas abscess--a review and update on the literature. Int J Surg. 2012;10:466-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mynter H. Acute psoitis. Buffalo Med Surg J. 1881;21:202-210. |

| 3. | Mallick IH, Thoufeeq MH, Rajendran TP. Iliopsoas abscesses. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:459-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taiwo B. Psoas abscess: a primer for the internist. South Med J. 2001;94:2-5. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tsantes AG, Papadopoulos DV, Vrioni G, Sioutis S, Sapkas G, Benzakour A, Benzakour T, Angelini A, Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF; World Association Against Infection In Orthopedics And Trauma W A I O T Study Group On Bone And Joint Infection Definitions. Spinal Infections: An Update. Microorganisms. 2020;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hsieh MS, Huang SC, Loh el-W, Tsai CA, Hung YY, Tsan YT, Huang JA, Wang LM, Hu SY. Features and treatment modality of iliopsoas abscess and its outcome: a 6-year hospital-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ouellette L, Hamati M, Flannigan M, Singh M, Bush C, Jones J. Epidemiology of and risk factors for iliopsoas abscess in a large community-based study. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:158-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tabrizian P, Nguyen SQ, Greenstein A, Rajhbeharrysingh U, Divino CM. Management and treatment of iliopsoas abscess. Arch Surg. 2009;144:946-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg. 1986;10:834-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yacoub WN, Sohn HJ, Chan S, Petrosyan M, Vermaire HM, Kelso RL, Towfigh S, Mason RJ. Psoas abscess rarely requires surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 2008;196:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Procaccino JA, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Oakley JR. Psoas abscess: difficulties encountered. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | López VN, Ramos JM, Meseguer V, Pérez Arellano JL, Serrano R, Ordóñez MAG, Peralta G, Boix V, Pardo J, Conde A, Salgado F, Gutiérrez F; GTI-SEMI Group. Microbiology and outcome of iliopsoas abscess in 124 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88:120-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang JJ, Ruaan MK, Lan RR, Wang MC. Acute pyogenic iliopsoas abscess in Taiwan: clinical features, diagnosis, treatments and outcome. J Infect. 2000;40:248-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu TL, Huang CH, Hwang DY, Lai JH, Su RY. Primary pyogenic abscess of the psoas muscle. Int Orthop. 1998;22:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Qureshi NH, O'Brien DP, Allcutt DA. Psoas abscess secondary to discitis: a case report of conservative management. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:73-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zissin R, Gayer G, Kots E, Werner M, Shapiro-Feinberg M, Hertz M. Iliopsoas abscess: a report of 24 patients diagnosed by CT. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yemisci OU, Cosar SN, Oztop P, Karatas M. Spondylodiscitis associated with multiple level involvement and negative microbiological tests: an unusual case. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1006-E1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jain V, India; Khanna V, India; Liu FX, China; Muthu S, India S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JL