Published online May 26, 2017. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v9.i5.466

Peer-review started: October 19, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Revised: January 10, 2017

Accepted: February 8, 2017

Article in press: February 13, 2017

Published online: May 26, 2017

Processing time: 217 Days and 4 Hours

We report a case of a 75-year-old male with history of lung adenocarcinoma who presented with shortness of breath and frequent episodes of cough-induced syncope. A large pericardial effusion was found on echocardiogram suggestive of cardiac tamponade. Pericardiocentesis was done which improved the dyspnea and eventually resolved the syncope. There are only two other cases reported in the literature with cough-induced syncope in the setting of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade. Our clinical vignette also highlights the importance of pulsus paradoxus identification in patients with cough induced syncope to rule out cardiac tamponade since this is the most sensitive physical finding for its diagnosis.

Core tip: Cough-induced syncope should be a hint towards the consideration of either pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade. Aside from the medical history and the diagnostic imaging modalities to include echocardiogram and chest computed tomography, clinical evaluation to explore pulsus paradoxus is imperative which has a high sensitivity in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. Timely diagnosis of cardiac tamponade because of these clues translate into prompt intervention to prevent the deleterious complications associated with it.

- Citation: Ramirez R, Lasam G. Cough induced syncope: A hint to cardiac tamponade diagnosis. World J Cardiol 2017; 9(5): 466-469

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v9/i5/466.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v9.i5.466

Cough-induced syncope is a validated rare phenomenon which denotes cough as the etiology of the syncope and has been linked with chronic obstructive disease and constrictive pericarditis. It is very rare to have cough-induced syncope in a case of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade with only two other reported cases in the literature. Therefore, we describe a case of cough-induced syncope in an elderly gentleman with cardiac tamponade, elaborating further the pathophysiology behind this rare occurrence.

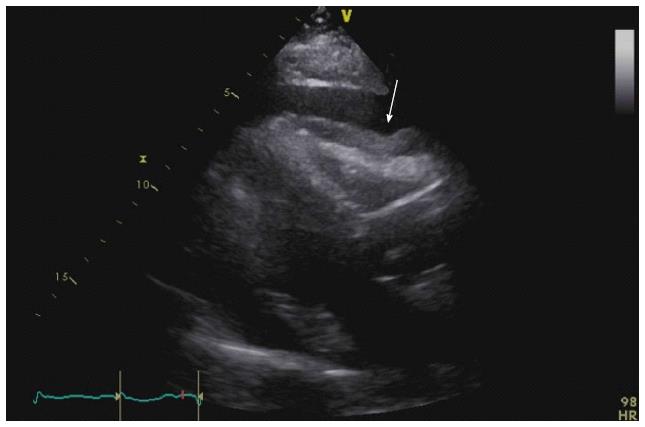

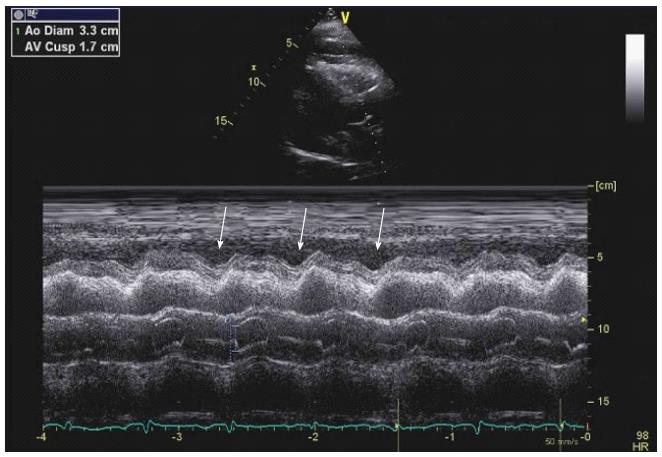

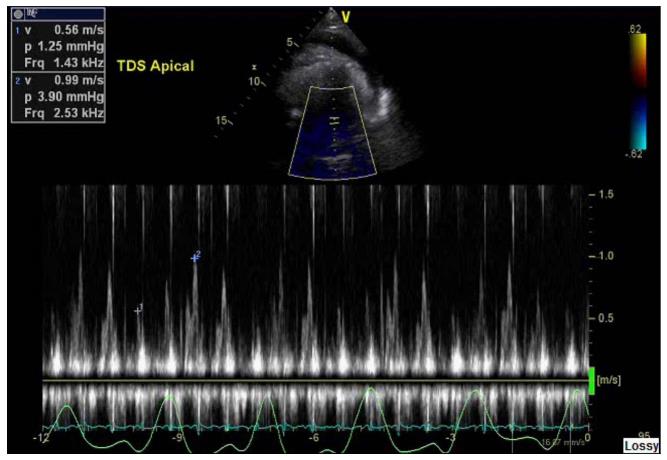

A 75 years old male with known history of stage 4 adenocarcinoma of the lung with recent right lung biopsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia and peripheral vascular disease presented with symptoms of increased shortness of breath for several days before hospitalization accompanied by cough with subsequent syncopal episodes. He had three syncopal episodes, two of them witnessed and were associated with coughing spells, lasting for 30 s to 1 min with complete recovery thereafter. No seizure-like activity was noted during the syncopal event. Prior to this presentation, he had never had a syncopal episode. The patient’s syncope was not associated with other precipitants including laughter and micturition. On admission to the hospital, he was hypertensive with a blood pressure of 151/88 mmHg and with a pulse rate of 100. General appearance was apparent for occasional cough with no signs of cyanosis nor worsening shortness of breath. Further examination revealed mild diminished breath sounds at the bases. Cardiac evaluation showed sinus tachycardia with a soft 2/6 systolic murmur at the apex and a pulsus paradoxus of 16 mmHg but no note of muffled heart sounds, distended neck veins or peripheral edema. Neuroexamination was intact and nonfocal. Pericardial effusion was considered immediately on admission because of his medical history, his symptoms, and the pulsus paradoxus which was confirmed later on by imaging studies. Hemogram revealed mild anemia (12.5 g/dL) and leukocytosis (12.8/nL). Electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus tachycardia (103 bpm) with intraventricular conduction delay but no low voltage complexes. No evident electrical alternans appreciated. Carotid ultrasound was done during his hospitalization which demonstrated no evidence of hemodynamically significant stenosis of the carotid system bilaterally and with normal antegrade flow of the vertebral arteries. Chest radiograph showed right pleural effusion. Chest computed tomography confirmed worsening bilateral pleural effusion as well as pericardial effusion but with no pulmonary embolus. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a large pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic indentation and collapse suggestive of tamponade (Figure 1) which was also evident on the M-mode (Figure 2). Mitral valve inflow E wave velocity showed greater than 25% respiratory variation also suggestive of tamponade physiology (Figure 3). The cardiothoracic surgery team was involved to move forward with a pericardial window. Pericardiocentesis was done and drained 600 mL of hemorrhagic fluid. Subsequently, thoracentesis was performed and drained 500 mL of serosanguineous pleural fluid. Pericardial and pleural fluid cytology revealed adenocarcinoma. After drainage of both pericardial and pleural effusion, his dyspnea improved significantly and subsequently his cough-induced syncope resolved.

Cough-induced syncope is a well-recognized but uncommon phenomenon in which the cough is the main culprit of the syncope[1]. It is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and constrictive pericarditis[2], although it is very rare to have cough induced syncope in a case of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade[3]. The proposed pathophysiology is multifactorial wherein there is a more exaggerated drop in blood pressure in response to cough compared to patients with other causes of syncope[4]. Also, the cough increases intrathoracic pressure, which decreases blood return to the heart and cardiac output, which is already reduced by the cardiac tamponade or moderate/large pericardial effusion. This phenomenon has been reported with even small pericardial effusions[5]. The combination of these events leads to cerebral hypoperfusion resulting to syncope. In subacute cardiac tamponade, these events occur over days to weeks and is usually associated with neoplastic, uremic or idiopathic pericarditis; it may be asymptomatic early in the course, but once intracardiac pressures reach a critical value, the patients develop symptoms of increased filling pressures and limited cardiac output and syncopal events[6]. There are two reported cases in the literature of moderate pericardial effusion associated with cough-induced syncope which also presented with pulsus paradoxus with a drop of > 15 mmHg systolic blood pressure but no evidence of echocardiographic criteria for tamponade[1,3]. Pulsus paradoxus greater than 10 mmHg with a pericardial effusion increases the likelihood of tamponade (likelihood ratio, 3.3; 95%CI: 1.8-6.3), while a pulsus paradoxus of 10 mmHg or less lowers the likelihood (likelihood ratio, 0.03; 95%CI: 0.01-0.24)[7]. Sensitivity of pulsus paradoxus for tamponade exceeds 80% and is higher than any other single physical finding although its specificity is only 70%[8]. Echocardiogram’s sensitivity is not significantly superior than clinical examination with reported sensitivity of the echocardiographic findings of right atrial collapse ranging from 50% to 100% and specificity ranging from 33% to 100%. Its sensitivity in identifying right ventricular collapse ranges from 48% to 100% whereas specificity ranges from 72% to 100%[9,10]. In one of the reported cases of cough induced syncope, the pericardial effusion was from metastatic non-small cell carcinoma, while the other case was secondary to suspected viral pericarditis in which pericardiocentesis of both cases afforded complete resolution of cough-syncope syndrome cycle[1,3].

It is important to consider either pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade in any case of cough-induced syncope. Pulsus paradoxus has a high sensitivity in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade and should therefore be checked in every patient with cough-induced syncope, consequently, can provide early diagnosis and intervention.

This is an interesting clinical vignette on syncope that was precipitated by cough which may serve as a clue to consider the diagnosis of pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade.

The patient presented with progressive shortness of breath accompanied by cough with subsequent syncopal episodes, noted clinically to have pulsus paradoxus, and was found out to have a pericardial effusion with tamponade physiology on echocardiocardiogram.

Cerebrovascular accident, vasovagal syncope, seizure.

Pericardial and pleural fluid cytology revealed adenocarcinoma.

Chest computed tomography showed both pericardial effusion and bilateral pleural effusion but with no pulmonary embolus while transthoracic echocardiography revealed a large pericardial effusion with tamponade.

Surgical drainage of the pericardial and pleural fluid afforded significant improvement of dyspnea and resolution of cough-induced syncope.

Cough-induced syncope is a very rare occurrence that has been associated with evolving pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade with only two similar cases reported in the literature.

Pulsus paradoxus is a drop in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mmHg during inspiration which is a sign of cardiac tamponade or pericarditis.

Pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade should be considered in patients with cough-induced syncope especially if accompanied by pulsus paradoxus which has a high sensitivity in such case.

The report has clinical interest.

| 1. | El-Osta H, Ashfaq S. Cough-induced syncope as an unusual manifestation of pericardial effusion. Kansas J Med. 2008;53-55. |

| 2. | Dhar R, Duke RJ, Sealey BJ. Cough syncope from constrictive pericarditis: a case report. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19:295-296. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Saseedharan S, Kulkarni S, Pandit R, Karnad D. Unusual presentation of pericardial effusion. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:219-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Benditt DG, Samniah N, Pham S, Sakaguchi S, Lu F, Lurie KG, Ermis C. Effect of cough on heart rate and blood pressure in patients with “cough syncope”. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saito Y, Donohue A, Attai S, Vahdat A, Brar R, Handapangoda I, Chandraratna PA. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography. 2008;25:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E. Pericardial Diseases. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Tenth Edition. Hopkins WE, LeWinter MM (ed): Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, USA 2015; 1636-1657. |

| 7. | Curtiss EI, Reddy PS, Uretsky BF, Cecchetti AA. Pulsus paradoxus: definition and relation to the severity of cardiac tamponade. Am Heart J. 1988;115:391-398. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Roy CL, Minor MA, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA. 2007;297:1810-1818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guntheroth WG. Sensitivity and specificity of echocardiographic evidence of tamponade: implications for ventricular interdependence and pulsus paradoxus. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kronzon I, Cohen ML, Winer HE. Diastolic atrial compression: a sensitive echocardiographic sign of cardiac tamponade. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:770-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bloomfield DA, Wittmann T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL