Published online Jul 26, 2013. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v5.i7.265

Revised: June 10, 2013

Accepted: July 4, 2013

Published online: July 26, 2013

Processing time: 106 Days and 17.2 Hours

Cardiovascular adverse events in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) are rare, but the early recognition of such events is crucial. We describe a case of a non-coronary myocardial infarction (MI) during the initial treatment period with pyridostigmine bromide in a female patient with MG. Clinicians should be cautious about the appearance of potential MI in patients with MG. A baseline electrocardiogram is advocated, when the early recognition of the MI clinical signs and the laboratory findings (myocardial markers) are vital to the immediate and appropriate management of this medical emergency, as well as to prevent future cardiovascular events. In this case report possible causes of myocardial adverse events in the context of MG, which may occur during the ongoing treatment and the clinical course of the disease, are discussed.

Core tip: Cardiovascular adverse events in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) are rare, but the early recognition of such events is crucial. We describe a case of a non-coronary myocardial infarction during the initial treatment period with pyridostigmine bromide in a female patient with MG. In this case report possible causes of myocardial adverse events in the context of MG, which may occur during the ongoing treatment and the clinical course of the disease, are discussed.

- Citation: Zis P, Dimopoulos S, Markaki V, Tavernarakis A, Nanas S. Non-coronary myocardial infarction in myasthenia gravis: Case report and review of the literature. World J Cardiol 2013; 5(7): 265-269

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v5/i7/265.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v5.i7.265

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a neuromuscular disorder characterized by weakness and fatigability of skeletal muscles. The number of available acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction is decreased because of an antibody-mediated autoimmune attack. Anticholinesterase medications are widely used to treat MG as they act by blocking hydrolysis of acetylcholine by acetylcholinesterase, consequently allowing acetylcholine to interact repeatedly with the limited number of acetylcholine receptors[1]. Apart from their muscarinic side effects, it has been shown that they can rarely cause cardiovascular side effects[2,3].

A 71-year-old female patient presented with a 4-wk history of worsening dysphagia and dysarthria. The edrophonium test that was performed in the emergency department was positive and therefore she was admitted to the Department of Neurology for further investigation and management. Past medical history included arterial hypertension well controlled on carvedilol and diet controlled dyslipidaemia. There was no history of diabetes, smoking or alcohol abuse. The rest of the medical history included a hip replacement surgery 12 mo prior to the current admission, which was complicated by deep venous thrombosis for which she received oral anticoagulant therapy for 12 mo. Finally, she was receiving a low-dose benzodiazepine on an as-required basis for anxiety disorder.

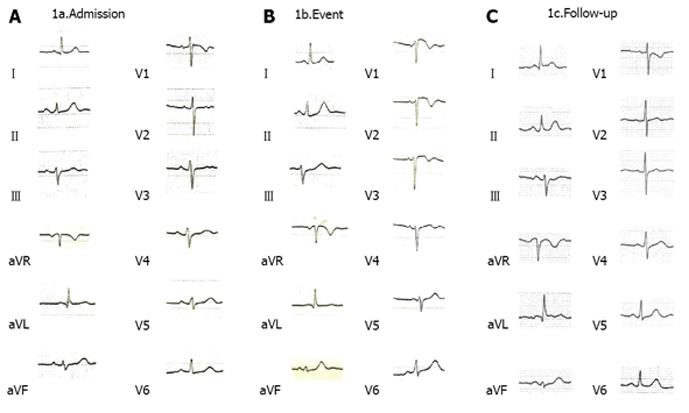

On admission the patient was alert and orientated with normal observations (blood pressure 140/74 mmHg, pulse 94/min, saturation 96% on FiO2 21%). The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed no signs of ischemia (Figure 1) and routine blood and biochemical tests were within normal values [haemoglobin 15.0 g/dL, serum glucose 83 mg/dL, urea 47 mg/dL, creatinine 0.76 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 32 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 16 IU/L, potassium 5.0 mmol/L, sodium 136 mmol/L]. Thyroid hormones were within normal limits. Neurological examination revealed mild proximal weakness in all four limbs, dysphagia and nasal speech. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

A diagnosis of MG was confirmed by positive rapid decremental responses of muscle action potentials to repetitive nerve stimulation and an elavated anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody count (titer 135 nmoles/L, normal values < 0.5 nmoles/L). Pyridostigmine bromide 60 mg tds and prednisolone, 10 mg A were commenced to treat MG.

Three days later muscarinic side effects such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps and salivation appeared while there was a significant improvement in neurological examination with regards to dysarthria and dysphagia. On the 4th day the patient complained of chest pain (with a duration of less than 30 min) accompanied by an intense sense of discomfort (emotional stress similar to an acute panic attack). There were no changes in the ECG and serial measurements of troponin, creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB, AST, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ProBNP levels were normal.

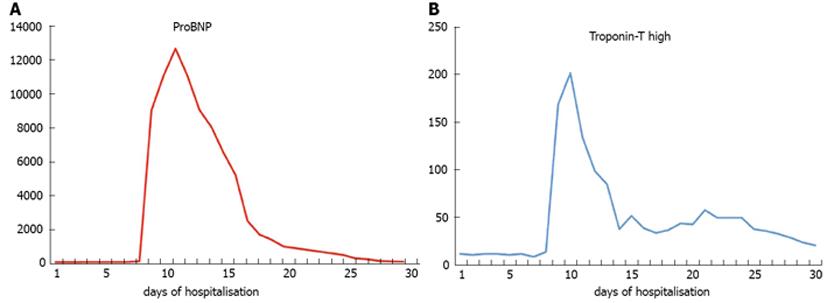

However, the frequency of such episodes of chest pain was increased from one every two days to twice a day and on day 10th the ECG revealed ST elevation in leads V1-V2 and T-wave abnormalities (Figure 1) with a subsequent significant elevation in troponin and ProBNP level (Figure 2). At that point blood pressure was 160/80 mmHg, pulse 69/min and oxygen saturation 96% (on oxygen nasal cannula, 2 L/min). Chest radiography was within normal limits, D-dimers were within normal values and the arterial blood gases did not show hypoxaemia and hypocapnia consistent with pulmonary embolism, therefore the latter was highly unlikely in our differential diagnoses. A subsequent spiral chest CT, with intravenous contrast, performed a few days later confirmed that there was no evidence of pulmonary embolism.

Based on the ECG and the increase in troponin and ProBNP levels a diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) was made and the patient was transferred to the intensive coronary care unit where treatment with nitrates, aspirin, clopidogrel and heparin was initiated. The cardiac ultrasound showed concentric hypertophy of the left ventricle (left ventricle ejection fraction 55%) with anteroseptal hypokinesia and type I diastolic dysfunction.

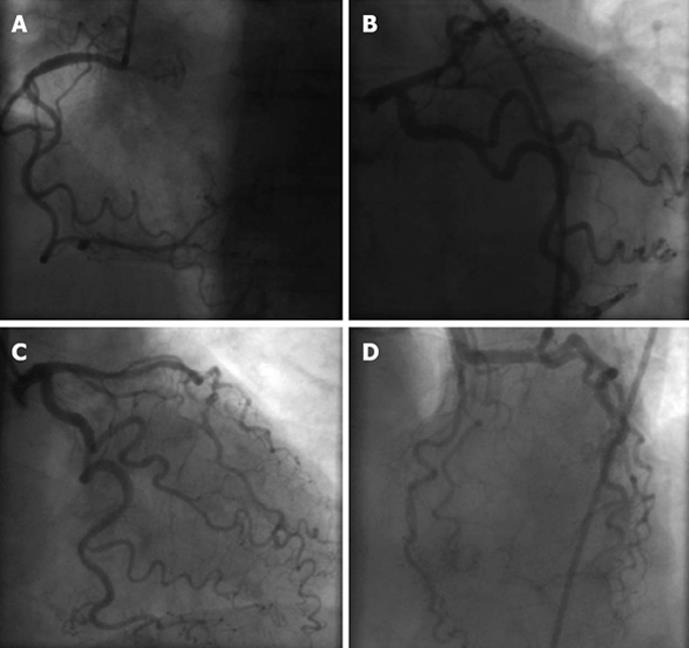

The chest pain resolved within hours. The patient underwent coronary angiography a few days later (as she did not consent to the procedure in the acute phase), which revealed a normal right coronary artery and a narrowing of less than 30% in the left anterior descending (Figure 3). Moreover, serial measurements of CK, AST and LDH did not show significant variation. The patient remained afebrile and the C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate values were normal.

During her hospital stay the patient was further investigated with chest axial computed tomography, which revealed a type A thymoma (N1M0) that was successfully surgically removed. Because of the initial difficulty in weaning from the mechanical ventilation a tracheostomy was performed and she was transferred to the medical intensive care unit. Her pyridostigmine dose was gradually reduced and was eventually stopped. The patient continued to receive only prednisolone in a high dose (75 mg/d), which was gradually reduced to 30 mg once daily.

The patient presented with weakness acquired during the intensive care unit (ICU) stay, which was gradually improved, tracheostomy was removed and she was discharged from the hospital in a generally good clinical condition. The neurological examination for MG was unremarkable at hospital discharge.

However, one month later, while she was in a sitting position, talking with her relatives she had a sudden cardiac death as reported from the last phone follow-up communication.

We present a case of a non-coronary MI in a patient with MG. A non-coronary MI, defined alternatively as a MI with normal coronary arteries, is a medical condition, which has been described in the literature for more than 30 years[4]. Its prevalence varies between 1% and 12% depending on the definition of “normal” coronary arteries, which usually includes no luminal irregularities (strict definition) or arteries with some degree of stenosis (less than 30%)[5-7].

Patients with MG under treatment complain frequently of the anticholinesterase medications muscarinic side effects, including diarrhea, abdominal cramps, salivation and nausea. However, cardiovascular adverse events in MG are rare. They occur mainly as a consequence of the MG treatment and less frequently in the context of a MG crisis through a possible immunological mechanism.

To the best of our knowledge three cases of cardiovascular side effects in patients with myasthenia gravis induced by anticholinesterase medication have been reported so far; a case of coronary spastic angina induced by ambenonium chloride[2], a case of coronary spastic angina induced by distigmine bromide[3] and a case of coronary vasospasm secondary to hypercholinergic crisis caused by pyridostigmine[8]. Cases of coronary vasospasm have also been described in anaesthetic practice where anticholinesterases are used to reverse the action of non-depolarizing muscle relaxants[9].

The exact mechanism under which cardiovascular side effects during treatment with acethylcholinesterase inhibitors occur remains unknown. However, it is well recognized that the coronary artery response to acethylcholine is very sensitive, constricting abnormally when the endothelium is damaged, in contrast to normal coronary arteries showing coronary vasodilation by acethylcholine[2]. One possible mechanism is that since pyridostigmine inhibits acetylcholinesterase in the synaptic cleft, thus slowing down the hydrolysis of acetylcholine and increasing the attachment of acetylcholine to the limited acetylcholine receptors, the exposure of coronary artery to acethylcholine might be increased. Furthermore, the use of prednisone decreases the anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody and enhances the effect of pyridostigmine[2].

In MG cardiovascular side effects can also occur during intravenous immunoglobin infusion (IVIg). IVIg has been associated with several possible adverse reactions including induction of a hypercoagulable state. IVIg-induced hypercoagulability has been associated with both non-ST elevation myocardial infarction[10] and ST elevation myocardial infarction[11]. The risk of acute MI seems to be increased with the use of high-dose IVIg in older individuals as well, especially those with at least one cardiovascular risk factor[12,13]. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has also been observed in a patient during plasmapheresis treatment for myasthenic crisis[14]. In our case, the cardiac ultrasound during the MI did not show any contractile dysfunction suggestive of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Moreover, in our case the patient neither received IVIg nor did she undergo plasmapheresis.

Previous case studies have indicated a possible link between MG and cardiovascular disorders[15-18]. It has also been suggested that myocarditis may occur in MG through the effects of striational muscle antibodies that cross-react with both skeletal muscles and myocardial tissue[16]. However, our patient remained afebrile, C-reactive protein and CK levels were normal and ECG did not show diffuse T-wave inversion. For these reasons myocarditis was an extremely unlikely diagnosis of our case.

In a recent case report it was shown that acute emotional stress may be a triggering factor for both Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and MG crisis[19], the mechanisms, however, remain unclear. In our case report acute emotional stress was involved in myocardial infarction presentation and might also have been a triggering factor even though-contrary to that case report[19]-a MG crisis was not manifested. The exact role of emotional stress is unclear in our case presentation as emotional stress can be both a precipitant and a consequence of the MI itself in a patient with a history of an anxiety disorder.

As our patient was haemodynamically stable with normal arterial blood gases, no evidence of sepsis and no anaemia, we believe that her MI did not occur because of demand ischemia but due to coronary vasospasm. The time interval between treatment initiation with pyridostigmine bromide and the myocardial infarction suggests that there may be a link between the two events. Moreover, apart from the pyridostigmine and the prednisolone there were no other changes in our patient’s drug regime. The subsequent sudden death of the patient, however, occurred while she was not on pyridostigmine and is, therefore, against this hypothesis.

The coronary slow flow phenomenon is characterized by angiographically normal coronary arteries with delayed opacification of the distal vasculature[20]. Although slow coronary flow can induce abortive sudden death[21] our patient did not have risk factors such as smoking that could have caused endothelial dysfunction. Further studies are needed to explore a possible pathophysiological link between MG and non-coronary MI.

Our patient suffered a sudden cardiac death a few months after the first MI while she was not on pyridostigmine bromide but only on prednisolone. Unfortunately, autopsy was not performed to identify the exact cause of death and to identify whether the two incidents, the MI and the cardiac death, share a common pathophysiological mechanism. However, being on prednisone, which decreases the antiacetylcholine receptor antibody levels, might have still induced an iatrogenic hypercholinergic crisis. Another possible explanation is that a sudden arrhythmic cardiac event (ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia) may be the cause of sudden death due to the recent history of MI.

We excluded Takotsubo cardiomyopathy based on the cardiac ultrasound, which did not show any relevant contractile dysfunction. However, we did not perform a ventriculography to confirm this. Moreover, we have ruled out pulmonary embolism based on the normal arterial blood gases and D-dimers titer, which was normal. The spiral chest CT, with intravenous contrast, that took place few days later was normal.

Finally, we did not measure anti-striatal antibodies and we did not perform a magnetic resonance scan of the heart, so we cannot rule out the possibility that MG had an indirect autoimmune adverse effect in the myocardial tissue of our patient; however, the presence of these antibodies have not been associated with an isolated myocardial infarction so far. Despite the fact that we cannot exclude that the MG itself has been involved with the non-coronary MI, the patient, at the time of the MI, was stable with regards to the MG symptoms and as she was not in MG crisis, and therefore the link between MG and MI is less likely.

In conclusion, we describe a case of a non-coronary MI during the initial treatment period with pyridostigmine bromide in a female patient with MG. Clinicians should be cautious about the appearance of potential MI in patients with MG. A baseline ECG is advocated, when the early recognition of the MI clinical signs and the laboratory findings (myocardial markers) are vital to the immediate and appropriate management of this medical emergency, as well as to prevent future cardiovascular events.

We express gratitude to the patient’s family. We would also like to thank Dr. Elli Kontogeorgi and Dr. Dimitiros Karakalos for their helpful contribution to the clinical management of the patient. Finally, we are sincerely thankful to Dr. Rosie Rogers, for the language revision of the manuscript.

| 1. | Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1797-1810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 992] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Suzuki M, Yoshii T, Ohtsuka T, Sasaki O, Hara Y, Okura T, Shigematsu Y, Hamada M, Hiwada K. Coronary spastic angina induced by anticholinesterase medication for myasthenia gravis--a case report. Angiology. 2000;51:1031-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yamabe H, Yasue H, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Obata K, Oshima S. Coronary spastic angina precipitated by the administration of an anticholinesterase drug (distigmine bromide). Am Heart J. 1990;120:211-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Iuliano L, Micheletta F, Napoli A, Catalano C. Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alpert JS. Myocardial infarction with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Da Costa A, Isaaz K, Faure E, Mourot S, Cerisier A, Lamaud M. Clinical characteristics, aetiological factors and long-term prognosis of myocardial infarction with an absolutely normal coronary angiogram; a 3-year follow-up study of 91 patients. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1459-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: a changing philosophy. JAMA. 2005;293:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Comerci G, Buffon A, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Ramazzotti V, Romagnoli E, Savino M, Rebuzzi AG, Biasucci LM, Loperfido F, Crea F. Coronary vasospasm secondary to hypercholinergic crisis: an iatrogenic cause of acute myocardial infarction in myasthenia gravis. Int J Cardiol. 2005;103:335-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kido K, Mizuta K, Mizuta F, Yasuda M, Igari T, Takahashi M. Coronary vasospasm during the reversal of neuromuscular block using neostigmine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:1395-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mizrahi M, Adar T, Orenbuch-Harroch E, Elitzur Y. Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infraction after High Dose Intravenous Immunoglobulin Infusion. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:861370. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Barsheshet A, Marai I, Appel S, Zimlichman E. Acute ST elevation myocardial infarction during intravenous immunoglobulin infusion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1110:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stenton SB, Dalen D, Wilbur K. Myocardial infarction associated with intravenous immune globulin. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:2114-2118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elkayam O, Paran D, Milo R, Davidovitz Y, Almoznino-Sarafian D, Zeltser D, Yaron M, Caspi D. Acute myocardial infarction associated with high dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion for autoimmune disorders. A study of four cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arai M, Ukigai H, Miyata H. [A case of transient left ventricular ballooning (“Takotsubo”-shaped cardiomyopathy) developed during plasmapheresis for treatment of myasthenic crisis]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2004;44:207-210. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hofstad H, Ohm OJ, Mørk SJ, Aarli JA. Heart disease in myasthenia gravis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;70:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Suzuki S, Utsugisawa K, Yoshikawa H, Motomura M, Matsubara S, Yokoyama K, Nagane Y, Maruta T, Satoh T, Sato H. Autoimmune targets of heart and skeletal muscles in myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1334-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Johannessen KA, Mygland A, Gilhus NE, Aarli J, Vik-Mo H. Left ventricular function in myasthenia gravis. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bansal V, Kansal MM, Rowin J. Broken heart syndrome in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:990-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beydoun SR, Wang J, Levine RL, Farvid A. Emotional stress as a trigger of myasthenic crisis and concomitant takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yetkin E, Turhan H, Erbay AR, Aksoy Y, Senen K. Increased thrombolysis in myocardial infarction frame count in patients with myocardial infarction and normal coronary arteriogram: a possible link between slow coronary flow and myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Amasyali B, Turhan H, Kose S, Celik T, Iyisoy A, Kursaklioglu H, Isik E. Aborted sudden cardiac death in a 20-year-old man with slow coronary flow. Int J Cardiol. 2006;109:427-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Li YY, Kusmic C, Sethi A, Mariani J, Campo JM, Kounis NG, Rognoni A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ