Published online Nov 26, 2011. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v3.i11.359

Revised: August 19, 2011

Accepted: August 26, 2011

Published online: November 26, 2011

AIM: To investigate the patient characteristics, relationship between the Logistic EuroSCORE (LES) and the observed outcomes in octogenarians who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR).

METHODS: Two hundred and seventy three octogenarians underwent AVR between 1996 and 2008 at Bristol Royal Infirmary. Demographics, acute outcomes, length of hospital stay and mortality were obtained. The LES was calculated to characterize the predicted operative risk. Two groups were defined: LES ≥ 15 (n = 80) and LES < 15 (n = 193).

RESULTS: In patients with LES ≥ 15, 30 d mortality was 14% (95% CI: 7%-23%) compared with 4% (95% CI: 2%-8%) in the LES < 15 group (P < 0.007). Despite the increase in number of operations from 1996 to 2008, the average LES did not change. Only 5% of patients had prior bypass surgery. The LES identified a low risk quartile of patients with a very low mortality (4%, n = 8, P < 0.007) at 30 d. The overall surgical results for octogenarians were excellent. The low risk group had an excellent outcome and the high risk group had a poor outcome after surgical AVR.

CONCLUSION: It may be better treated with transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

- Citation: Kesavan S, Iqbal A, Khan Y, Hutter J, Pike K, Rogers C, Turner M, Townsend M, Baumbach A. Risk profile and outcomes of aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. World J Cardiol 2011; 3(11): 359-366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v3/i11/359.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v3.i11.359

Calcific aortic stenosis is the most common structural cardiac disease in an ever growing elderly population. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has now become a realistic choice for treating high risk, elderly patients and has raised interest in the treatment of aortic valve disease in octogenarians[1-5]. Despite the high mortality and morbidity associated with symptomatic untreated aortic stenosis, a recent survey showed that over 30% of elderly patients did not receive surgical treatment[6,7].

Conventional surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) can be performed with good success in selected patients[8-10]. However, increasing age is a significant independent predictor of postoperative mortality[11-14]. The perceived risk associated with advanced age and comorbidity may have led clinicians to adopt a conservative approach to treatment of critical aortic stenosis[7,11]. The presence of coronary artery disease requiring coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a risk factor for surgical mortality, when compared with isolated AVR[15]. Frailty is also frequently quoted as a risk factor, but is hard to quantify. Hence, there is a growing need for risk stratification and evaluation of outcomes after surgical AVR and TAVI in octogenarians in the modern era.

Thus, whilst there are reports showing acceptable overall mortality and morbidity for surgical AVR they may still represent a select population[15,16]. Selection criteria for TAVI are clinical and anatomical. With a growing number of TAVI performed worldwide, we considered it important to assess the surgical outcomes of octogenarians undergoing AVR in our institution. We postulated that there would be a subgroup of patients that could be identified as being at high risk for surgery by applying the risk assessment tool currently used for patient selection into our TAVI program. Furthermore, we postulated that some patient subgroups with relative contraindications such as previous cardiac surgery might be under-represented.

A retrospective review was performed on patients who underwent isolated, primary AVR and AVR with CABG from 1996 to August 2008 at Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol, United Kingdom. Clinical details were obtained from a central cardiac database. Preoperative demographics, predictors of in-hospital mortality and postoperative outcomes were documented. Case records were reviewed and data relevant for the calculation of risk score and outcomes were verified individually.

The selection of patients for cardiac surgery was at the discretion of individual referring physicians, cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. The surgical technique, valve selection and implantation technique were determined by the individual cardiac surgeon. Postoperative care was provided by the intensive care unit, followed by the high dependency unit and the cardiac ward. Duration of stay in the intensive care and high dependency units and perioperative adverse events were documented in the clinical notes.

A Logistic EuroSCORE (LES) of ≥ 15% is used to define “high risk”[2] in the initial TAVI programs. The patients were separated into LES ≥ 15% and < 15% for analysis. To further quantify the risk, surgical patients were also analyzed by quartile of risk.

Deaths after hospital discharge were obtained by linking with the NHS Strategic Tracing Service (NSTS).

Evidence of elevation of cardiac biomarkers (creatine kinase, CK-MB or troponin elevation above 0.05 μg/L) associated with electrocardiographic changes of ST depression or ST elevation identified a myocardial infarction. An elevated fasting blood glucose value of 6.9 mmol/L was considered sufficient to establish a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. A serum creatinine value above 200 μmol/L was classified as renal impairment. Pulmonary disease included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and emphysema. Previous percutaneous coronary intervention was defined as coronary angioplasty with or without coronary stent insertion prior to AVR.

Patients with previous stroke included patients with a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or transient ischemic attack (TIA). CVA was diagnosed with imaging evidence of a cerebral infarct with or without a persistent neurological deficit. Persistence of a neurological deficit beyond 24 h was also defined as a CVA. TIA was diagnosed in patients experiencing a transient neurological deficit which resolved in 24 h without any long term neurological sequelae. Patients with documented evidence of claudication pain associated with or without an ankle brachial pressure index of 0.9 were considered to have peripheral vascular disease.

Coronary artery disease was defined as coronary arteries with > 50%. Depending on the number of major coronary arteries involved, patients were classified as having single, double or triple vessel coronary artery disease. Ejection fraction was quantified by biplane Simpson method as a percentage and presented as 3 categories (< 30%, 30%-49%, 50% and above).

The EuroSCORE and LES were calculated with the help of an online risk calculator (http://www.euroscore.org/).

Continuous measures are summarized by the mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range (IQR) if the distribution was skewed. Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages. The primary comparisons were made between patients with LES < 15 and those with LES ≥ 15. Binary outcomes were compared using odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI. Survival and length of stay outcomes were compared using hazard ratios (HR) from the Cox proportional hazards model. For survival, surviving patients were censored at 2 mo prior to the update from NSTS (chosen because the majority of deaths are reported to NSTS within 2 mo). For hospital stay, patients who died before discharge were censored at the date of death. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were also used to illustrate long-term survival.

Mortality was also compared between (1) quartiles of LES; (2) isolated AVR surgery vs AVR + CABG surgery; and (3) eras of time (1996-2000, 2001-2004 and 2005-August 2008), with the aim of reflecting the variability in surgical practice and outcomes in the 3 different eras.

The acquired data was anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality. All analyses were performed using Stata version 10.1 (Stata Co., TX, United States).

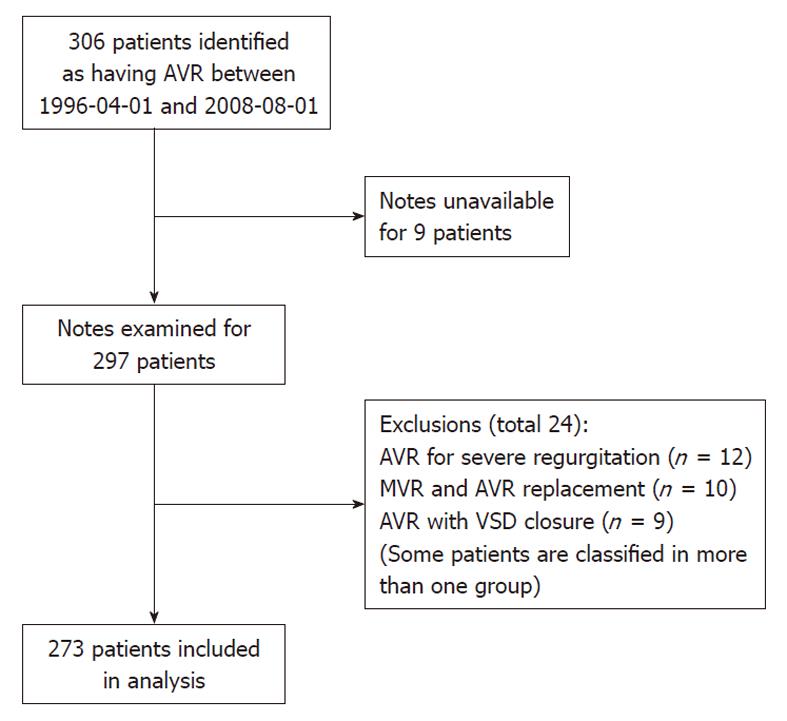

Three hundred and six patients underwent surgical AVR between April 1996 and August 2008; 297 case notes were examined as 9 notes were not obtainable. Patients undergoing double valve replacement (mitral and aortic valve) and complex procedures involving AVR with ventricular septal defect closure were excluded from the study (Figure 1). A total of 24 patients were excluded due to categorization of some patients in more than one of these groups. Therefore 273 patients formed the study population, 80 in the group with LES ≥ 15 and 193 in the group with LES < 15.

The demographics of patients in the LES ≥ 15 and LES < 15 groups are shown in Table 1. Approximately equal numbers of patients underwent isolated AVR (n = 140) and AVR with CABG (n = 133).

| All patients (n = 273) | LES < 15 (n = 193) | LES≥15 (n = 80) | P value | |

| Gender (male) | 128 (47) | 90 (47) | 38 (48) | 0.900 |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 82.7 ± 2.35 | 82.4 ± 2.21 | 83.5 ± 2.53 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||

| AVR | 140 (51) | 103 (53) | 37 (46) | 0.280 |

| AVR with CABG | 133 (49) | 90 (47) | 43 (54) | |

| Previous MI | ||||

| None | 231 (85) | 180 (93) | 51 (64) | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 90 d | 26 (10) | 6 (3) | 20 (25) | |

| > 90 d | 16 (6) | 7 (4) | 9 (11) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (11) | 27 (14) | 3 (4) | 0.014 |

| Renal impairment | 11 (4) | 4 (2) | 7 (9) | 0.011 |

| Previous PCI | 4 (2) | 0 | 4 (5) | 0.002 |

| Pulmonary disease | 47 (17) | 21 (11) | 26 (33) | < 0.001 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 13 (5) | 1 (1) | 12 (15) | < 0.001 |

| CVA/TIA | 42 (15) | 28 (15) | 14 (18) | 0.450 |

| PVD | 25 (9) | 12 (6) | 13 (16) | 0.009 |

| CAD | ||||

| None | 135 (50) | 100 (52) | 35 (44) | 0.590 |

| 1 vessel disease | 46 (17) | 33 (17) | 13 (16) | |

| 2 vessel disease | 42 (15) | 28 (15) | 14 (18) | |

| 3 vessel disease | 49 (18) | 31 (16) | 18 (23) | |

| Pathology | ||||

| AS | 239 (88) | 170 (88) | 69 (86) | 0.680 |

| AS with mild AR | 34 (12) | 23 (12) | 11 (14) | |

| Valve | ||||

| Mechanical | 15 (6) | 13 (7) | 2 (3) | 0.160 |

| Biological | 258 (95) | 180 (93) | 78 (98) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 4 (2) | 0 | 4 (5) | 0.002 |

| Ejection fraction | ||||

| < 30% | 15 (6) | 0 | 15 (19) | < 0.001 |

| 30%-49% | 62 (23) | 37 (19) | 25 (31) | |

| 50% and above | 196 (72) | 156 (81) | 40 (50) | |

| EuroSCORE, median (IQR) | 9 (8-10) | 8 (8-9) | 11 (10-12) | |

| LES, median (IQR) | 11.1 (8.4-16.6) | 9.5 (7.9-11.6) | 20.7 (17.4-24.9) |

Outcomes by LES group are shown in Table 2. The incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction, CVA, bleeding, infection and the necessity for permanent pacemaker insertion was similar in both groups, although very few patients experienced any of these complications. There was some evidence of increased renal impairment in the LES ≥ 15 group (n = 18, 23%) compared to the LES < 15 group (n = 26, 14%), although this was not statistically significant at the 5% level (OR, 1.86: 95% CI: 0.96-3.64). Mortality to 30-d was increased for patients with LES ≥ 15 (n = 11, 14% vs n = 8, 4%; OR, 3.69; 95% CI: 1.42-9.55) and fewer patients were discharged home in the LES ≥ 15 group. Long-term survival was also reduced in the LES ≥ 15 group (HR, 2.12; 95% CI: 1.40-3.22). Median survival time was estimated to be 4.2 years (IQR, 1.8-5.9 years) in the LES ≥ 15 group and 8.7 years (IQR, 3.5-11.1 years) in the LES < 15 group. The overall duration of hospital stay was similar in the 2 groups, although high dependency unit stay was on average slightly longer in the LES ≥ 15 group.

| All patients (n = 273) | LES < 15 (n = 193) | LES≥15 (n = 80) | Effect (95% CI) | P value | |

| Stroke | 13 (5) | 8 (4) | 5 (6) | OR 1.54 (0.49-4.86) | 0.460 |

| MI | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 | ||

| Cardiac tamponade | 14 (5) | 7 (4) | 7 (9) | OR 2.55 (0.86.7.52) | 0.090 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 11 (4) | 8 (4) | 3 (4) | OR 0.90 (0.23-3.49) | 0.880 |

| Infection | 22 (8) | 15 (8) | 7 (9) | OR 1.14 (0.45-2.91) | 0.790 |

| Renal impairment | 44 (16) | 26 (14) | 18 (23) | OR 1.86 (0.96-3.64) | 0.070 |

| PPM insertion | 23 (8) | 14 (7) | 9 (11) | OR 1.60 (0.66-3.87) | 0.290 |

| Mortality | |||||

| 30 d | 19 (7) | 8 (4) | 11 (14) | OR 3.69 (1.42-9.55) | 0.007 |

| ≤ 90 d | 31 (11) | 16 (8) | 15 (19) | OR 2.55 (1.19-5.46) | |

| > 90 d | 22 (8) | 10 (5) | 12 (15) | 0.020 | |

| Discharge | |||||

| Home | 153 (56) | 118 (61) | 35 (44) | ||

| Other hospital or Ward | 97 (36) | 64 (33) | 33 (41) | ||

| Survival (yr), median (IQR) | 6.22 (3.00-10.94) | 8.74 (3.54-11.07) | 4.19 (1.83-5.94) | HR 2.12 (1.40-3.22 ) | < 0.001 |

| 1 yr postop (95% CI) | 87% (82%-90%) | 90% (85%-94%) | 79% (68%-86%) | ||

| 5 yr postop (95% CI) | 57% (49%-64%) | 64% (54%-72%) | 40% (26%-55%) | ||

| ICU stay | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | HR 0.86 (0.66-1.14) | 0.290 |

| Death pre ICU | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (5) | ||

| HDU stay | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 4 (2-5) | HR 0.67 (0.50-0.89) | 0.006 |

| Death pre HDU | 13 (5) | 5 (3) | 8 (10) | ||

| Ward stay | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4-9) | 6 (4-9) | 5 (4-8) | HR 1.16 (0.87-1.55) | 0.310 |

| Death pre ICU | 17 (6) | 7 (4) | 10 (13) | ||

| Overall, median (IQR) | 11 (8-15) | 11 (8-15) | 11 (8-15) | HR 0.89 (0.67-1.17) | 0.400 |

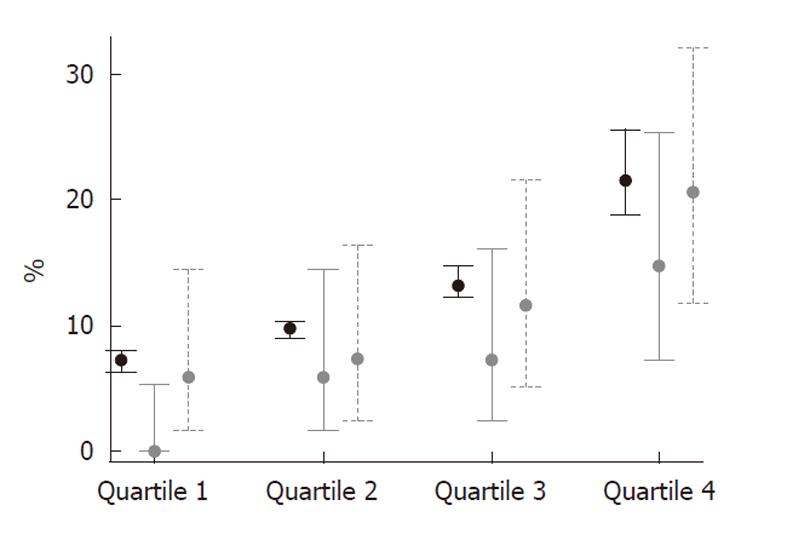

The LES distribution and 30-d mortality by LES quartiles is illustrated in Figure 2. As expected, mortality increased with increasing LES. Patients in the highest quartile were at particular risk (30-d mortality 15%; 95% CI: 7%-25%), whilst the lower risk quartiles showed excellent outcomes. The overall mortality in all risk quartiles was below the level predicted by the LES.

Although there were increasing numbers of patients operated over time, the LES and 30-d mortality of patients did not change markedly (Figure 3).

Survival of AVR patients was similar to that of AVR + CABG patients; the 30-d mortality of AVR was 6% (95% CI: 3%-11%), and of AVR + CABG was 8% (95% CI: 4%-14%). One-year survival was estimated to be 91% (95% CI: 85%-95%) in the AVR group compared with 82% (95% CI: 74%-88%) in the AVR + CABG group. Five-year survival was estimated to be 58% (95% CI: 46%-68%) in the AVR group and 57% (95% CI: 45%-67%) in the AVR + CABG group (Figure 4).

This analysis of surgical outcomes in octogenarians demonstrated the spectrum of operative risk and identified a low risk cohort with excellent acute and long-term results. Age alone should not be used as selection criteria for alternative non-surgical aortic valve implantation. Whilst the LES did not accurately predict mortality, the preoperative classification into lower or higher risk quartiles matched the incidence of adverse outcomes.

We used our surgical database to identify patients for this study. This database includes every patient operated at our center, so we were able to identify all eligible patients; only 9 patients were excluded due to their notes being unavailable. Using the database and the individual patient case notes we were able to obtain a clinical dataset similar to the dataset collected for our TAVI patients. We were able to use the LES to assess outcomes in patient groups of particular interest: low and high risk for morbidity and mortality.

We identified a subgroup, those in the highest LES risk quartile, with high mortality and morbidity. Outcomes for this subgroup have not been reported previously in the surgical literature. The fact that the LES was able to discriminate between very low risk and very high risk patients prior to surgery, justifies its use in the selection process for the transcatheter programs. Patients in the highest risk quartile had a mortality of 15% (95% CI: 7%-25%). Comparing our high risk cohort with those in TAVI registries adds further support to the argument that this group of high risk patients may benefit from the transcatheter approach. In the PARTNER B trial, the rate of death from any cause was 30.7% with TAVI compared to 50.7% with standard therapy (including balloon aortic valvuloplasty)[5]. The trial concluded that TAVI significantly reduced the rates of death from any cause, despite a higher incidence of major strokes and major vascular events.

We were also able to document excellent results in the lower risk quartiles. In the lowest quartile the surgical outcomes were excellent with no deaths within 30 d (95% CI: 0%-5%). Any enrollment from this patient group into a transcatheter valve program should be done with great caution, as it would be difficult to improve on the results of the conventional approach with the associated known long-term outcome. Hence, age on its own is a poor indicator of surgical risk and age over 80 alone should not be the sole indication for TAVI.

The number of patients treated with AVR in our center increased exponentially over the 12-year study period. The average risk score did not change significantly. This would suggest that while the absolute number of elderly patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis increased, the selection criteria for valve surgery did not expand into the very high risk cohort. There was an under-representation of patients with a prior history of CABG or patients with heavily calcified aorta (porcelain aorta). Prior revascularization is considered as a significant risk factor for surgical AVR, hence the under-representation which introduced a selection bias into the study. Whilst the LES was predictive of mortality, the selection of patients for surgery involved clinical criteria that were not reflected in the LES or any other risk score, such as subjective assessment of frailty.

Previous studies have shown that with good clinical judgment on the part of the surgical and multidisciplinary team selecting patients for surgery, good outcomes for AVR surgery with or without CABG in octogenarians were possible, with previously reported mortality figures of 8%-10%[17,18]. The mortality we report [6% (95% CI: 3%-11%) for AVR and 8% (95% CI: 4%-14%) for AVR and CABG] are consistent with this and are also concordant with previous reports[15]. The surgical results are better than predicted by the LES (predicted mortality 11%), which has been shown previously in other series[13,19].

An LES ≥ 15 is currently used as a criterion for enrollment in the Corevalve registry. In this higher risk surgical cohort, the mortality was 14% (95% CI: 7%-23%) and there was a 6% rate of stroke, a 9% rate of serious infection and 4% incidence of bleeding requiring transfusion, with a median stay in the intensive care unit of 2 d. Only 44% of these patients were then discharged home, and a further 41% went on to recover in district general hospitals or rehabilitation centers. The rate of new pacemaker implantations in this cohort was also higher than previously reported (11%). This could be explained by the selection of patients for the study, which included only the octogenarian population who are more prone for sino-atrial node fibrosis and disease. The median survival in years was 4.19 (range, 1.83-5.94) in the LES ≥ 15 group compared to 8.74 years (range, 3.54-11.07 years) in the LES < 15 group. The 1-year and 5-year survival was 79% (95% CI: 68%-86%) and 40% (95% CI: 26%-55%), respectively, in the LES ≥ 15 group compared to 90% (95% CI: 85%-94%) and 64% (95% CI: 54%-72%), respectively, in the LES < 15 group.

In our study, the LES tended to significantly overestimate the perioperative mortality risk in all quartiles (Figure 2).

Piazza et al[2] recently reported on the outcome of the first 646 patients in the Corevalve registry, and Thomas et al[6] reported on the SOURCE registry for the Edwards Sapien vlave. In both cohorts, the average LES was over 20. Large proportions of patients included in these registries were not offered surgery and therefore are not comparable with the patients we have presented. Nevertheless, the overall outcomes for TAVI compare favorably with our results in patients with LES ≥ 15, that would now be considered for the transcatheter approach. The SOURCE registry revealed a 1-year survival rate of 81.1% in transfemoral procedures and 72% in transapical procedures. The mortality in both TAVI registries was lower, as was the hospital stay and reported morbidity. The rate of new pacemaker implantation appeared higher in the Corevalve registry than in the Sapiens Edwards series, but the difference compared to our surgical results may not be clinically relevant. The encouraging outcomes add to the evolving body of clinical evidence demonstrating that TAVI is a viable option for this high risk population.

As previously reported, long-term survival after a successful operation was excellent; overall 57% (95% CI: 49%-64%) of patients were alive at 5 years. The median length of stay in hospital was 11 d (IQR, 8-15 d) and 56% (n = 153) of patients were discharged directly to home. The rest were either transferred to a local hospital for recuperation (36%, n = 97) or died prior to hospital discharge (8%, n = 22). Whilst these lengths of stay data are in keeping with other reports[13,18], they are significantly longer than those for younger patients undergoing AVR in our center. This observation, coupled with the increasing number of patients, has implications for intensive care and hospital bed resource planning Economic analyses of TAVI cohorts may show that the benefits of percutaneous procedures may extend to hospital stay.

In the TAVI registries we found a large proportion of patients with previous bypass surgery (20.4%)[2] whilst only 5% of our patients had undergone surgical coronary revascularization. A repeat operation does carry an increased risk, whilst prior bypass surgery has no impact on the technical feasibility or risk of a transcatheter valve implantation. Furthermore, a porcelain (heavily calcified) aorta, present in up to 6.6% in the TAVI series, was not described in any of our patients selected for surgery.

A Canadian study of TAVI identified patient factors that can help in selecting appropriate patients for the procedure and further improve outcomes[20]. The study concluded that the transfemoral or transapical approach did not determine worse outcomes as much as patient factors, such as pulmonary hypertension, severe mitral regurgitation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic kidney disease. Patients with a porcelain aorta (18%) or frailty (25%) exhibited acute outcomes similar to the rest of the study population. Porcelain aorta patients tended to have better survival rate at 1-year follow-up. Hence, it underscores the importance of patient selection to improve short- and long-term outcomes after TAVI.

This was a retrospective, single center series spanning 12 years of practice. The results improved with time, and hence surgical results in the modern era may now be better than reported for the whole cohort. No direct statistical analysis was attempted for comparison of this patient cohort with the patients enrolled into TAVI programs. Hence, all discussion and conclusions rely on descriptive parameters.

Whilst risk scoring systems are well developed for coronary artery bypass surgery, the optimal risk scoring system for aortic valve surgery is yet to be defined. Nevertheless, in this cohort, the LES was able to identify a group of patients at high risk of surgical AVR with a less favorable outcome, and a low risk group with an excellent outcome after surgical AVR. New scoring systems that take into account parameters relevant for surgical and transcatheter valve implantation are needed to characterize patients better and to guide selection of the best treatment option There is a clear under-representation of patients with a history of prior CABG or porcelain aorta in our cohort compared to published TAVI registries, which reflects the surgical selection process in the past and highlights these patient groups as particularly relevant for alternative treatment options The outcomes after successful surgical AVR are good. However, the documented attrition rate in octogenarians is higher than in younger populations and this must be recognized when data from TAVI registries are interpreted.

Severe aortic stenosis occurs in the aging population, and the definitive treatment for the condition has been surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) for the past few decades. Technological and scientific advancement has enabled us to perform percutaneous AVR in this era. Two types of percutaneous aortic valves are available: Edward Sapien and CoreValve. The selection criteria need to be robust so that high risk patients who are considered not suitable for surgical AVR can be offered percutaneous AVR. The present article highlights the risk factor profile of these patients by using the Logistic EuroSCORE (LES), which enables us to identify those at high risk and those at low risk.

Percutaneous AVR is considered a safe alternative to surgical AVR in the octogenarian population with comorbidities. Studies are being conducted on 2 types of valves: Edward Sapien and the CoreValve. The type of approach is also being investigated: transfemoral, transapical, subclavian. Selection criteria and the appropriate imaging techniques before and during implantation are under intense debate.

The major innovations in the past few years have been the size of the CoreValve. Now it is available in 3 sizes. The surgeon can choose the appropriate size depending on the annular dimensions. Technology is advancing so that in future a retrievable percutaneous aortic valve will become available. Expertise in this field will enable us to offer the procedure to even low risk group.

The present article helps us to identify high risk and low risk patients. The LES is an important scoring system to identify these cases. It is easy to apply in our daily practice.

Percutaneous AVR, transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a tissue heart valve is placed on a balloon-mounted catheter and guided via the femoral artery into the chambers of the heart and positioned directly over the diseased aortic valve. The balloon is then inflated to secure the valve in place.

LES is used as a risk scoring tool to identify high risk group and low risk group. Frequently, it overestimates the predicted mortality. The article clearly shows the difference between the predicted mortality and the observed mortality. Hence patients should not be denied percutaneous aortic valve implantation based on LES alone. Each scoring system has its own pitfalls. The authors have clearly explained the difficulties of using the LES as the only scoring system and additional factors (frailty) need to be taken into account.

| 1. | Grube E, Schuler G, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Linke A, Wenaweser P, Sauren B, Mohr FW, Walther T, Zickmann B. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in high-risk patients using the second- and current third-generation self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis: device success and 30-day clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 715] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Piazza N, Grube E, Gerckens U, den Heijer P, Linke A, Luha O, Ramondo A, Ussia G, Wenaweser P, Windecker S. Procedural and 30-day outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the third generation (18 Fr) corevalve revalving system: results from the multicentre, expanded evaluation registry 1-year following CE mark approval. EuroIntervention. 2008;4:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Al-Attar N, Antunes M, Bax J, Cormier B, Cribier A, De Jaegere P, Fournial G, Kappetein AP. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1463-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Webb JG, Pasupati S, Humphries K, Thompson C, Altwegg L, Moss R, Sinhal A, Carere RG, Munt B, Ricci D. Percutaneous transarterial aortic valve replacement in selected high-risk patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2007;116:755-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 784] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5086] [Cited by in RCA: 5643] [Article Influence: 352.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, Himbert D, Lefèvre T, Treede H, Eggebrecht H, Rubino P, Michev I, Lange R. Thirty-day results of the SAPIEN aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) Registry: A European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation. 2010;122:62-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 663] [Cited by in RCA: 661] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde JL, Vermeer F, Boersma E. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2255] [Cited by in RCA: 2306] [Article Influence: 100.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, Grosswald RD, Smith PK, Jones RH, Peterson ED. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients & gt; or = 80 years: results from the National Cardiovascular Network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:731-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huber CH, Goeber V, Berdat P, Carrel T, Eckstein F. Benefits of cardiac surgery in octogenarians--a postoperative quality of life assessment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1099-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Khan JH, McElhinney DB, Hall TS, Merrick SH. Cardiac valve surgery in octogenarians: improving quality of life and functional status. Arch Surg. 1998;133:887-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bramstedt KA. Aortic valve replacement in the elderly: frequently indicated yet frequently denied. Gerontology. 2003;49:46-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Craver JM, Puskas JD, Weintraub WW, Shen Y, Guyton RA, Gott JP, Jones EL. 601 octogenarians undergoing cardiac surgery: outcome and comparison with younger age groups. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1104-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Grossi EA, Schwartz CF, Yu PJ, Jorde UP, Crooke GA, Grau JB, Ribakove GH, Baumann FG, Ursumanno P, Culliford AT. High-risk aortic valve replacement: are the outcomes as bad as predicted? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:102-106; discussion 107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gulbins H, Malkoc A, Ennker J. Combined cardiac surgical procedures in octogenarians: operative outcome. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Asimakopoulos G, Edwards MB, Taylor KM. Aortic valve replacement in patients 80 years of age and older: survival and cause of death based on 1100 cases: collective results from the UK Heart Valve Registry. Circulation. 1997;96:3403-3408. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, Guthrie TJ, Keune JD, Schuessler RB, Pasque MK, Lawton JS, Moazami N, Moon MR. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: risk factors for early and late mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1651-1656; discussion 1656-1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chiappini B, Camurri N, Loforte A, Di Marco L, Di Bartolomeo R, Marinelli G. Outcome after aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thourani VH, Myung R, Kilgo P, Thompson K, Puskas JD, Lattouf OM, Cooper WA, Vega JD, Chen EP, Guyton RA. Long-term outcomes after isolated aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: a modern perspective. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1458-1464; discussion 1464-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Collart F, Feier H, Kerbaul F, Mouly-Bandini A, Riberi A, Mesana TG, Metras D. Valvular surgery in octogenarians: operative risks factors, evaluation of Euroscore and long term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rodés-Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A, Ye J, Dumont E, Feindel CM, Osten M, Natarajan MK, Velianou JL, Martucci G. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1080-1090. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Gian M Novaro, MD, Director, Echocardiography, Department of Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic Florida, 2950 Cleveland Clinic Boulevard, Weston, FL 33331, United States; Athanassios N Manginas, MD, FACC, FESC, Interventional Cardiology, 1st Department of Cardiology, Onassis Cardiac Surgery Center, 356 Sygrou Ave, Athens 17674, Greec

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM