Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.112857

Revised: September 9, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 161 Days and 2.4 Hours

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) substantially increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, including ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INO

To investigate PCATa differences and their diagnostic value for identifying INOCA in patients with T2DM.

This retrospective study involved 228 T2DM patients underwent CCTA and 120 healthy individuals. The mean PCATa values within the proximal segments of the three major coronary arteries were compared between groups. Further subgroup analysis was performed to assess the differences in PCTAa and clinical characteristics between T2DM patients with and without INOCA. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the independent risk factors for INOCA, and the receiver operating characteristic curves were generated to evaluate the diagnostic performance of each indicator.

Compared with controls, T2DM patients exhibited significantly higher PCATa values in all three major coronary arteries. Among them, those with concomitant INOCA showed further increases compared to those without INOCA (all P < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression identified age; female sex; elevated glycated hemoglobin; and increased PCATa in the LAD, LCX, and RCA as independent risk factors for INOCA. Receiver operating characteristic analysis showed good diagnostic performance for PCATa [LAD area under the curve (AUC) = 0.809; LCX AUC = 0.777; RCA AUC = 0.758], outperforming traditional clinical indicators (AUC = 0.731). Combining PCATa with clinical parameters yielded the highest diagnostic accuracy (LAD AUC = 0.851; LCX AUC = 0.842; RCA

Elevated proximal PCATa is an independent risk factor for INOCA in T2DM. Combining PCATa with clinical data improves diagnostic performance in this population.

Core Tip: This study reveals significantly increased pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation (PCATa) in the proximal segments of the left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary arteries in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly those with ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). PCATa serves as an independent imaging biomarker for identifying INOCA and demonstrated superior diagnostic performance compared with conventional clinical indicators. The combination of PCATa and clinical parameters further improves diagnostic accuracy. These results highlight the potential value of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived PCATa in early risk stratification and noninvasive identification of INOCA in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Citation: Su KX, Jiang SY, Pang CF, Yang F, Tang YQ, Li XG, He WF, Li R. Coronary computed tomography angiography adipose tissue attenuation in diabetic patients with myocardial ischemia and non-obstructive coronary arteries. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 112857

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/112857.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.112857

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by disturbances in glucose and lipid metabolism. Long-standing metabolic abnormalities contribute to multisystem damage, with cardiovascular disease being the leading cause of mortality among affected individuals[1]. In individuals with T2DM, sustained hyperglycemia contributes to oxidative stress and inflammatory response[2]. These alterations promote the development of atherosclerotic plaque and play a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease[3]. In light of these risks, the current clinical guidelines recommend the use of standardized coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) in patients with diabetes mellitus to facilitate the early detection of cardiovascular risk[4]. Although CCTA serves as an effective modality for early screening and surveillance of coronary artery disease, its diagnostic utility is primarily limited to identifying anatomically significant stenotic lesions. Consequently, it may fail to elucidate ischemic symptoms in patients without obstructive coronary stenosis. Recent evidence indicates that obstructive coronary artery disease is identified in

Currently, the diagnosis of INOCA in clinical practice primarily relies on a combination of CCTA/digital subtraction angiography, electrocardiographic findings, and laboratory indicators. However, this approach remains complex, and certain parameters may be confounded by recent pharmacologic interventions[9]. Therefore, there is a growing need for a stable and reliable biomarker capable of identifying INOCA. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that inflammation in the pericoronary region plays a central role in the pathogenesis of INOCA, in the absence of significant coronary stenosis. In this regard, the pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation (PCATa) index, derived from CCTA, has gained attention as a novel noninvasive imaging biomarker for assessing coronary inflammation in clinical and research settings[10]. When coronary artery disease is present, vascular endothelial cells release proinflammatory cytokines that initiate paracrine signaling to the surrounding pericoronary adipose tissue, leading to lipid metabolic alterations detectable as measurable changes in PCATa. Consequently, the comprehensive evaluation of pericoronary adipose tissue characteristics using CCTA may help identify patients with INOCA in the context of T2DM.

Elevated PCATa is an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[11]. Given the shared state of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation in both NAFLD and T2DM, evidence derived from NAFLD populations may have translational relevance to individuals with T2DM. However, the current data regarding the application of PCATa in diabetes mellitus populations remain limited, particularly in the context of evaluating the INOCA risk. Although existing research supports the potential utility of PCATa in assessing coronary inflammation[12], its diagnostic accuracy for identifying INOCA in T2DM patients has yet to be validated. The present study aimed to evaluate the predictive value of PCATa for INOCA risk in T2DM by integrating clinical indicators and CCTA imaging parameters. The study findings may provide imaging-based evidence to support the early identification of high-risk individuals and inform timely clinical decision-making.

The present study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines stipulated in Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (Approval No. 2024ER648-1). The requirement for obtaining informed consent from the patients was waived due to the retrospective nature of the present study. Our retrospective analysis included patients with clinically diagnosed T2DM who underwent CCTA at the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College between January 2020 and August 2024.

T2DM was diagnosed in accordance with the 2023 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for diabetes and cardiovascular disease[13]. The T2DM diagnosis was established if any of the following criteria were met: (1) Presence of classic hyperglycemic symptoms accompanied by a random plasma glucose level of ≥ 11.1 mmol/L on at least two occasions, a fasting plasma glucose level of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L on at least two occasions, or a 2-hour plasma glucose level of

The diagnosis of INOCA was independently confirmed by two cardiologists according to established criteria[14,15]. Patients were diagnosed when the degree of coronary artery stenosis is < 50% coexisting with at least one objective indicator of myocardial ischemia: (1) Typical angina pectoris symptoms; (2) Ischemic changes on 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) during symptomatic episodes; (3) Evidence of stress-induced myocardial perfusion defects or regional ventricular wall motion abnormalities; and (4) Impaired coronary flow reserve.

The inclusion criteria were clinically diagnosed T2DM with completed CCTA examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) History of coronary stenting or coronary artery bypass grafting within the previous 3 months; (2) Presence of acute or chronic inflammatory disease; (3) Incomplete clinical datasets; (4) Poor-quality CCTA images (defined as an unmeasurable Agatston score due to motion artifacts); (5) Severe cardiac, pulmonary, or renal dysfunction, or allergy to iodinated contrast agents; (6) Congenital coronary artery anomalies (including origin, course, or developmental variants); and (7) ≥ 50% stenosis in any major coronary artery branch [i.e., left anterior descending artery (LAD), left circumflex artery (LCX), or right coronary artery (RCA)]. Ultimately, 228 T2DM patients were recruited in the present study; of these, 110 were diagnosed with INOCA, whereas 118 exhibited no evidence of coronary artery disease. Additionally, 120 healthy individuals undergoing routine health examinations at our institution who received CCTA were included as controls.

All patients underwent CCTA using a third-generation dual-source computed tomography (CT) scanner (SOMATOM Force, Siemens Healthineers, Germany). Prior to the examination, the heart rates of all participants were controlled, and respiratory training was conducted. For patients with baseline heart rates of > 80 beats per minute, intravenous metoprolol (25-100 mg) was administered to reduce the heart rate to ≤ 80 beats per minute. Patients also received respiratory training to ensure breath-hold at end-expiration. During image acquisition, patients were positioned supine with a head-first orientation. ECG electrodes were placed on the left anterior chest wall to optimize R-wave signal detection. After identifying the optimal scan center, prospective ECG-triggered CCTA was performed during end-expiratory breath-hold. The scanning parameters were as follows: Rotation time of 280 milliseconds, tube current of 400 mA, detector collimation of 256 mm × 0.625 mm, and ECG gating during the 35% to 75% phase of the RR interval. Tube voltage was automatically modulated between 70 kV and 120 kV to optimize the image quality and minimize radiation exposure. All CCTA images were reconstructed using standard kernel with 50% adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction-V (ASiR-V, GE Healthcare, IL, United States). Diastolic phase images were selected for subsequent analysis. To minimize the influence of varying tube voltage on PCATa measurements, we applied standardized correction factors derived from previously validated studies[16], adjusting all PCATa values to an equivalent 120 kV peak. Specifically, PCATa values obtained at lower tube voltages (e.g., 70 kV peak, 100 kV peak) were divided by the corresponding voltage-specific correction coefficients to ensure consistency across scans.

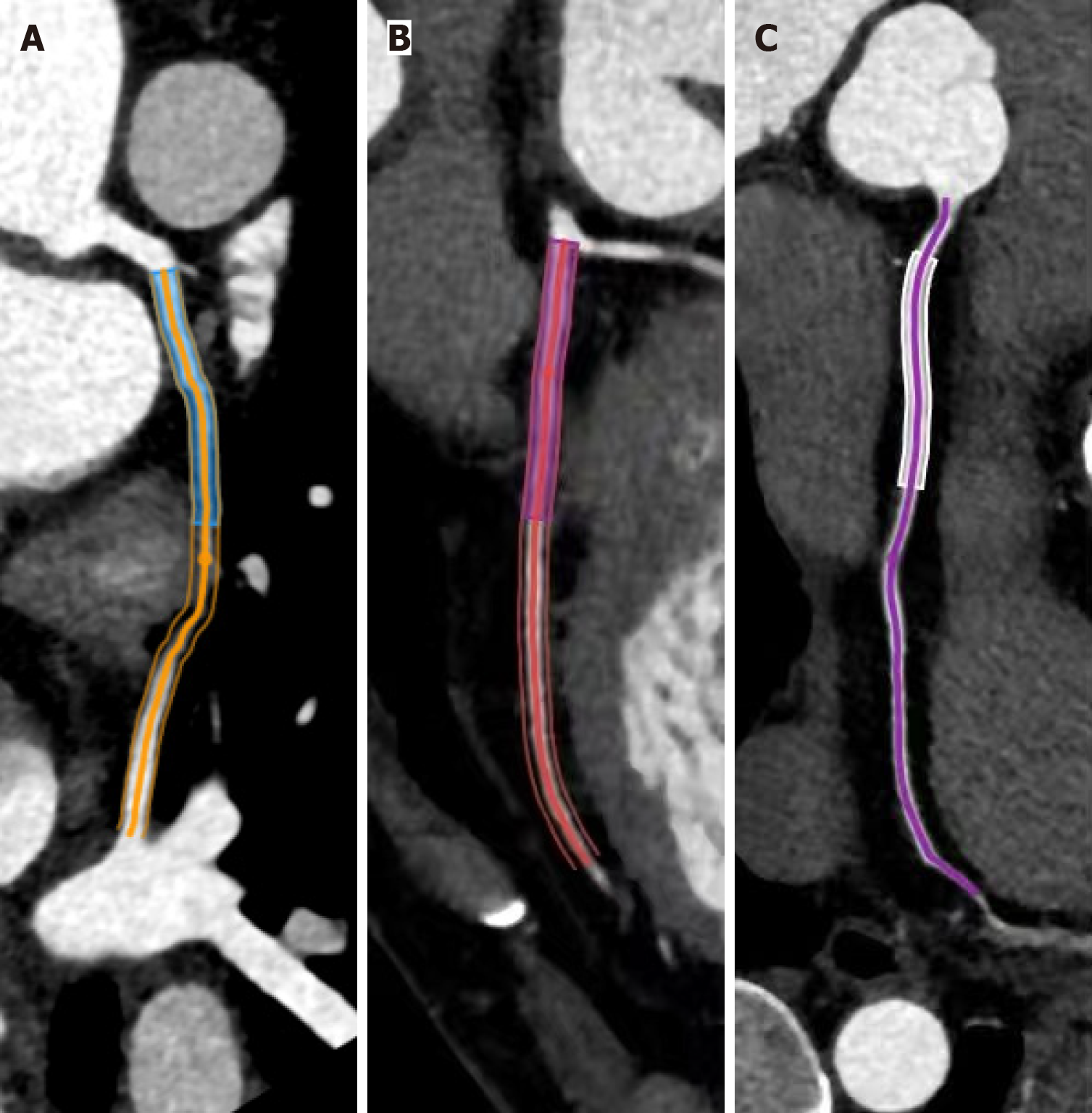

CCTA image analysis was performed using dedicated cardiovascular software (Shukun Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China), and coronary artery segmentation was conducted using internally developed proprietary software (TIMESlice, version 4.0.19, Shenyang, China). PCATa was quantified as the mean CT value of adipose voxels (-190 HU to -30 HU) within a radial distance equivalent to the vessel diameter surrounding the outer coronary wall[17]. Standardized measurements were acquired in the proximal RCA segment (10-50 mm from the ostium, avoiding the aortic wall effects), proximal LAD, and proximal LCX, with all segments analyzed using an established methodology, summarized in Figure 1. Inter-observer and intra-observer variability analyses of PCATa were performed based on the coefficient of variation (CV) to evaluate the measurement reproducibility of PCATa. Variability was calculated using the formula: CV (%) = (s/X) × 100, where s denotes the SD and X represents the mean of the cross-sectional areas. Precision was expressed as an average%CV. The initial measurements were considered as the final PCATa when the CV was below 15%.

The coronary artery calcium score (CACS) was calculated from non-contrast-enhanced CT scans using uAI Sphere software (United Imaging Intelligence Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) according to the Agatston method[18]. CACS was determined by multiplying the area of each calcified lesion (mm2) by a weighting factor based on the peak CT attenuation. The density scores were assigned as follows: 1 for 130-199 HU, 2 for 200-299 HU, 3 for 300-399 HU, and 4 for ≥ 400 HU. The total CACS for each coronary artery was obtained by summing all individual calcified plaque scores within that vessel. Additionally, patients were stratified into three groups based on their total CACS values: CACS = 0, CACS 1-99, and CACS ≥ 100[19].

All coronary segments were subjected to semi-automated plaque quantification using dedicated analysis software. The segments with a diameter of < 2 mm, those affected by severe motion artifacts, or those with insufficient contrast opacification were excluded from the analysis. The software automatically identified scan-specific thresholds to quantify the plaque components within the manually defined regions of interest. The total plaque volume was calculated for each patient. All automated outputs were reviewed and manually adjusted when necessary to ensure measurement accuracy.

All measurements were independently performed by two cardiovascular radiologists who were blinded to the patients’ clinical and prognostic information. After each observer conducted separate assessments of the lesions, the average of their measurements was calculated and adopted as the final quantitative value.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 27.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and R studio (version 4.3.3). The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess the normality of continuous variables. Normally distributed data were compared using independent t and presented as mean ± SD, while non-normally distributed data were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. A continuous variable that contains a substantial proportion of zero values may be converted into a binary variable (e.g., presence vs absence) to minimize the effect of zero inflation on statistical comparisons and preserve analytical validity. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and summarized as frequencies and percentages. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent risk factors associated with INOCA in T2DM patients. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of PCATa as a predictor by including statins, antiplatelet agents, and insulin (commonly prescribed drugs with known anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects) as additional covariates in the multivariate models. Diagnostic performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with area under the curve (AUC) comparisons conducted via DeLong’s test. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) analyses were conducted to further assess the incremental value of PCATa over conventional clinical factors. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The present study included 228 participants (mean age 66.71 ± 10.44 years; 58.33% female), of whom 110 (48.24%) were diagnosed with INOCA. The baseline clinical characteristics of the control, non-INOCA, and INOCA groups are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the healthy control group, the T2DM group were significantly older and had significantly higher proportion of females, lower body mass index (BMI), and higher systolic blood pressure, triglyceride, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (all P < 0.05). The T2DM group was further divided into two subgroups according to the presence of INOCA. Compared with the non-INOCA group, the INOCA group were older and had a higher proportion of females and smokers. This group also exhibited lower BMI and TC, LDL-C, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Additionally, the fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c levels were significantly higher and the platelet and lymphocyte counts were significantly lower in the INOCA group. The INOCA group also demonstrated higher usage rates of antiplatelet agents, statins, and insulin therapy (all P < 0.05).

| Healthy control group (n = 120) | Non-INOCA group (n = 118) | INOCA group (n = 110) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 56 (50-62) | 66 (58-74)a | 69 (60.75-76)a,b |

| Gender (female) | 66 (55.0) | 61 (51.7) | 72 (62.5)a,b |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.82 (20.81-24.21) | 24.98 (23.42-27.07)a | 24.22 (21.74-26.31)a,b |

| Smoking | 29 (24.16) | 34 (28.8) | 46 (41.8)a,b |

| Drinking | 32 (26.67) | 36 (30.5) | 35 (31.8) |

| SBP, mmHg | 122 (112-130) | 133 (124-141.25)a | 137 (123.75-148.5)a |

| DBP, mmHg | 77.63 ± 12.21 | 82.36 ± 10.85a | 80.40 ± 13.98 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| TG, mmol/L | 1.19 (0.92-1.60) | 1.49 (1.01-2.31)a | 1.35 (1.05-1.94)a |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.60 (2.19-3.08) | 2.55 (1.90-3.14) | 2.12 (1.50-2.65)a,b |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.64 ± 1.06 | 4.71 ± 1.22 | 4.10 ± 1.22a,b |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.27 (1.04-1.48) | 1.12 (0.96-1.35)a | 1.08 (0.89-1.25)a,b |

| Fast glucose, mmol/L | 5.09 (4.47-5.49) | 7.26 (6.07-8.42)a | 7.91 (6.75-10.43)a,b |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.87 (5.64-6.12) | 7.14 (6.68-7.85)a | 7.76 (7.02-9.46)a,b |

| WBC, × 10 9/L | 5.55 (4.81-7.14) | 6.43 (5.26-8.10) | 6.62 (5.28-8.01) |

| NEU, × 10 9/L | 3.44 (2.67-4.38) | 4.06 (3.16-5.27) | 4.17 (3.17-5.60) |

| LYM, × 10 9/L | 1.67 (1.34-2.03) | 1.75 (1.35-2.14) | 1.54 (1.18-1.84)b |

| MONO, × 10 9/L | 0.32 (0.26-0.42) | 0.38 (0.29-0.49) | 0.38 (0.31-0.51) |

| PLT, × 10 9/L | 196.18 ± 63.42 | 192.8 ± 57.88 | 175.95 ± 58.87b |

| Medication situation | |||

| Antiplatelet agents | 44 (37.3) | 74 (67.3)b | |

| Diuretics | 10 (8.5) | 15 (13.6) | |

| β-blockers | 23 (19.5) | 25 (22.7) | |

| ACEI/ARB | 31 (26.3) | 30 (27.3) | |

| Statins | 65 (55.1) | 86 (78.2)b | |

| CCBs | 39 (33.1) | 46 (41.8) | |

| Hypoglycemic agents | 72 (61.0) | 78 (70.9) | |

| Insulin therapy | 19 (16.1) | 43 (39.1)b | |

As summarized in Table 2, PCATa was significantly higher in T2DM patients (LAD: -89.81 ± 19.77 vs -77.31 ± 7.77; LCX:

| Healthy control group (n = 120) | Non-INOCA group (n = 118) | INOCA group (n = 110) | |

| PCATa (HU) | |||

| LAD | -89.81 ± 19.77 | -81.29 ± 5.87a | -73.03 ± 7.28a,b |

| LCX | -83.52 ± 8.09 | -74.45 ± 5.71a | -67.46 ± 6.68a,b |

| RCA | -92.69 ± 8.89 | -81.51 ± 6.90a | -74.02 ± 7.71a,b |

| Presence of coronary plaque | |||

| LAD | 46 (39.0) | 49 (44.54) | |

| LCX | 41 (34.7) | 47 (42.7) | |

| RCA | 38 (32.2) | 40 (37.0) | |

| CACS | |||

| 0 | 63 (53.38) | 51 (45.46) | |

| 1-99 | 55 (46.61) | 53 (49.09) | |

| ≥ 100 | 0 | 6 (5.4) | |

To assess the reproducibility of PCATa measurements, we calculated intra- and inter-observer %CV. The intra-observer %CVs were 3.46% for LAD, 3.67% for LCX, and 3.45% for RCA, while the corresponding inter-observer %CVs were 5.54%, 5.30%, and 5.27%. These findings indicate that PCATa measurements are stable and reproducible across both repeated and independent assessments.

To identify the independent risk factors for INOCA in T2DM patients, logistic regression analysis was conducted. In the univariate analysis, advanced age, female sex, lower BMI, history of smoking, elevated levels of LDL-C, TC, fasting plasma glucose, and HbA1c, diabetes duration of > 10 years, reduced platelet count, and higher diastolic PCATa values across all three major coronary branches were associated with the presence of INOCA (all P < 0.05). Subsequent multi

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.031 | 1.005-1.058 | 0.021 | 1.037 | 1.008-1.067 | 0.013 |

| Gender (female) | 1.844 | 1.079-3.150 | 0.025 | 2.242 | 1.230-4.086 | 0.008 |

| Smoking | 1.769 | 1.024-3.056 | 0.041 | |||

| Drinking | 1.063 | 0.607-1.862 | 0.831 | |||

| BMI | 0.892 | 0.823-0.966 | 0.005 | 0.888 | 0.816-0.968 | 0.007 |

| SBP | 1.010 | 0.996-1.024 | 0.169 | |||

| DBP | 0.987 | 0.967-1.008 | 0.235 | |||

| TG | 0.872 | 0.734-1.037 | 0.122 | |||

| LDL-C | 0.717 | 0.544-0.946 | 0.019 | |||

| TC | 0.655 | 0.519-0.828 | < 0.001 | |||

| HDL-C | 0.377 | 0.160-0.889 | 0.026 | |||

| Fast glucose | 1.217 | 1.092-1.357 | < 0.001 | |||

| HbA1c | 1.589 | 1.293-1.953 | < 0.001 | 1.587 | 1.283-1.963 | < 0.001 |

| WBC | 1.026 | 0.907-1.160 | 0.688 | |||

| NEU | 1.075 | 0.942-1.227 | 0.282 | |||

| LYM | 0.724 | 0.489-1.074 | 0.108 | |||

| MONO | 1.726 | 0.324-9.180 | 0.522 | |||

| PLT | 0.995 | 0.990-1.000 | 0.033 | |||

| Time since diagnose T2DM | ||||||

| < 5 | 0.010 | |||||

| 5-10 | 1.987 | 0.850-4.643 | 0.113 | |||

| > 10 | 2.363 | 1.338-4.172 | 0.003 | |||

| LAD-PCATa | 1.230 | 1.159-1.305 | < 0.001 | 1.246 | 1.168-1.329 | < 0.001 |

| LCX-PCATa | 1.205 | 1.140-1.274 | < 0.001 | 1.207 | 1.138-1.281 | < 0.001 |

| RCA-PCATa | 1.172 | 1.113-1.234 | < 0.001 | 1.164 | 1.105-1.227 | < 0.001 |

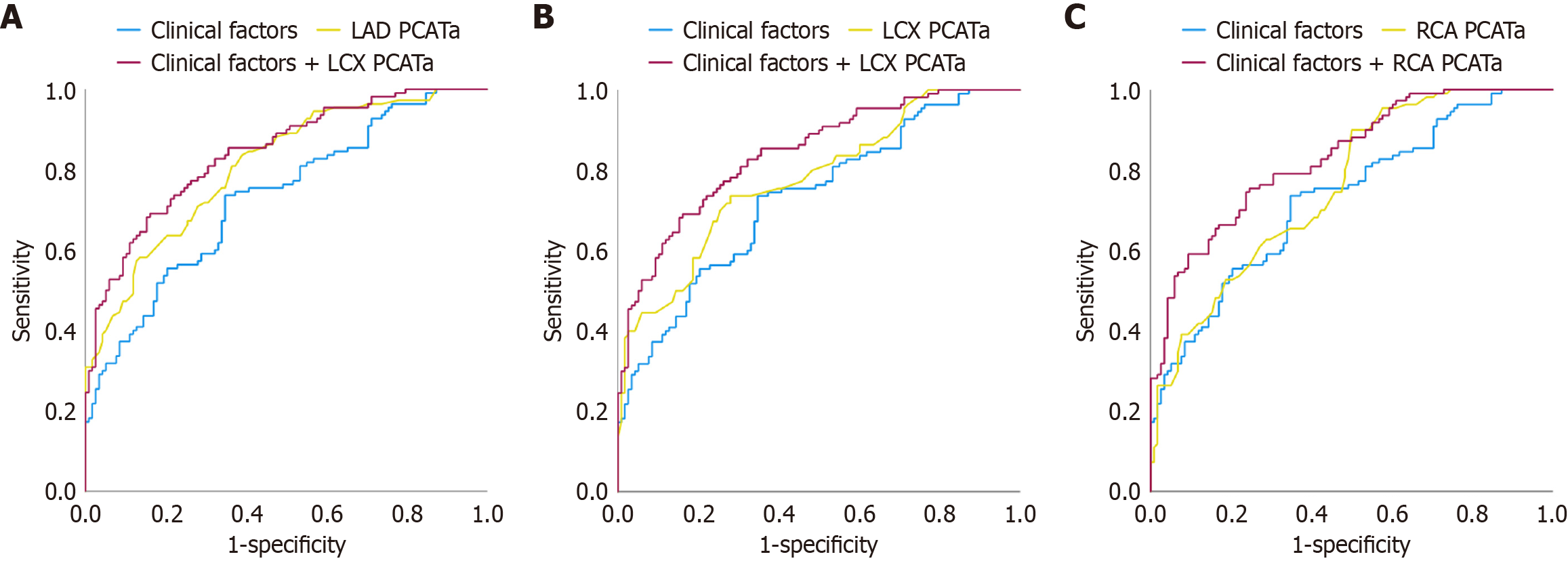

Following the ROC curve analysis in LAD, LCX, and RCA, the cutoff values of LAD (-79.38 HU), LCX (-71.27 HU), and RCA (-81.52 HU) assisted in discriminating between the INOCA and non-INOCA cases (Figure 2). The AUCs for PCATa in the LAD (0.809), LCX (0.777), and RCA (0.758) were higher than the individual clinical risk factors (0.731), although the differences did not reach statistical significance. When the clinical risk factors were combined with the PCATa values from these three vessels, the diagnostic performance was further improved (clinical + LAD: 0.851; clinical + LCX: 0.842; clinical + RCA: 0.841, all P < 0.05). This result indicates that combining the imaging and clinical parameters enhances the ability to identify INOCA in T2DM patients, as compared to either indicator alone. Table 4 summarizes the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity values of each parameter. We conducted NRI and IDI analyses to assess the added diagnostic value of PCATa. The inclusion of PCATa substantially improved risk classification for INOCA in patients with T2DM: LAD-PCATa: NRI = 0.59 (95%CI: 0.38-0.8, P < 0.001) and IDI = 0.14 (95%CI: 0.10-0.18, P < 0.001); LCX-PCATa: NRI = 0.41 (95%CI: 0.20-0.62, P < 0.001) and IDI = 0.07 (95%CI: 0.04-0.09, P < 0.001); RCA-PCATa: NRI = 0.34 (95%CI: 0.16-0.56, P < 0.001) and IDI = 0.07 (95%CI: 0.04-0.10, P < 0.001). These findings indicate that PCATa provides incremental discriminative power for identifying INOCA beyond conventional clinical risk factors (Table 5).

| Cutoff | AUC | 95%CI | SEN | SEP | |

| Clinical factors | 0.731 | 0.666-0.795 | 0.745 | 0.644 | |

| LAD PCATa | -79.38 | 0.809 | 0.755-0.864 | 0.836 | 0.610 |

| LCX PCATa | -71.27 | 0.777 | 0.717-0.836 | 0.736 | 0.720 |

| RCA PCATa | -81.52 | 0.758 | 0.698-0.819 | 0.900 | 0.500 |

| Clinical factors + LAD PCATa | 0.851 | 0.802-0.900 | 0.755 | 0.805 | |

| Clinical factors + LCX PCATa | 0.842 | 0.792-0.909 | 0.691 | 0.839 | |

| Clinical factors + RCA PCATa | 0.841 | 0.792-0.890 | 0.655 | 0.839 |

| NRI (95%CI) | P value | IDI (95%CI) | P value | |

| LAD PCATa | 0.59 (0.38-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.14 (0.10-0.18) | < 0.001 |

| LCX PCATa | 0.41 (0.20-0.62) | < 0.001 | 0.07 (0.04-0.09) | < 0.001 |

| RCA PCATa | 0.34 (0.16-0.56) | < 0.001 | 0.07 (0.04-0.10) | < 0.001 |

The present study that enrolled 228 participants evaluated the differences in PCATa at the proximal segments of the three major coronary branches using CCTA between T2DM patients and healthy controls. Furthermore, T2DM patients were stratified based on the presence or absence of concomitant INOCA to investigate the potential of PCATa and clinical indicators for early risk identification. Our study results demonstrated that PCATa was significantly higher in T2DM patients than in healthy controls and was further elevated in those with concomitant INOCA, as compared to those without INOCA. The subsequent diagnostic performance analysis indicated that PCATa outperformed the conventional clinical risk factors in distinguishing INOCA. Additionally, the integration of imaging and clinical parameters led to further improvements in diagnostic accuracy.

Given the high incidence of cardiovascular disease in T2DM patients, routine CCTA screening has become a clinical consensus, especially for those with an elevated cardiovascular risk[20]. The current guidelines recommend an active intervention in patients with coronary artery stenosis of > 50%, as identified by CCTA[21]. However, the cases with < 50% stenosis are frequently overlooked in clinical settings. Despite the absence of significant luminal obstruction, these patients remain at an increased risk of developing cardiovascular complications[22]. In such cases, conventional imaging markers (such as fractional flow reserve or plaque volume) may exhibit limited sensitivity in detecting early-stage or inflammation-driven disease processes, thereby impeding timely risk identification and management. The present study highlights the central role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of INOCA. In particular, inflammation-induced hypercontraction of the vascular smooth muscle cells and coronary microvascular spasms are recognized as key contributors to its development[23,24]. As an imaging biomarker of vascular inflammation, pericoronary adipose tissue offers a dynamic reflection of pathological changes within the coronary arteries. An elevated PCATa has been identified as a sensitive indicator of localized inflammatory activity[25], and its increase may precede the formation of plaques or onset of luminal stenosis detectable by conventional imaging techniques.

Our study demonstrated that the PCATa values of the three major coronary branches were significantly elevated in T2DM patients, as compared to normal controls, indicating a persistent inflammatory response in the pericoronary region. Previous studies have confirmed that T2DM is characterized not only by systemic chronic inflammation but also by localized inflammatory responses within the coronary arteries[26]. Notably, the severity of coronary endothelial dysfunction and inflammation has been shown to correlate positively with blood glucose levels[26], which aligns with our study findings. Furthermore, our subgroup analysis revealed that the PCATa values of the three major coronary branches were further elevated in T2DM patients with concomitant INOCA. This finding indicates the presence of a more pronounced pericoronary inflammatory response in this subgroup, which is possibly associated with inflammation-mediated mechanisms underlying the development of INOCA. PCAT, functioning as a dynamic endocrine and paracrine tissue[27], releases various proinflammatory mediators in response to inflammatory stimuli. These mediators infiltrate the adjacent vascular wall and contribute to endothelial dysfunction[28], subsequently altering the water-lipid composi

Notably, recent pharmacological treatments may affect PCATa values; however, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the extent of this influence. Specifically, statins, antiplatelet agents, and insulin, which are commonly prescribed drugs with known anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects, were included as covariates in the multivariate regression models. After adjustment, the association between PCATa and INOCA remained statistically significant across all three major coronary arteries. These findings indicate that pharmacological treatment did not substantially affect the diagnostic utility of PCATa in this patient population. This supports the robustness of our results and highlights the independent contribution of perivascular adipose tissue inflammation to the pathophysiology of INOCA in individuals with T2DM.

Additionally, the present study further screened relevant clinical risk factors and imaging parameters. Subsequently, the ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the diagnostic value of these indicators for the early identification of INOCA in T2DM patients. Our results demonstrated that the ROC curve based on the PCATa values of the three major coronary branches yielded a higher AUC value than that based on clinical risk factors alone, although the difference was not statistically significant. Notably, the ROC curve generated by combining the PCATa values and clinical risk factors showed significantly greater diagnostic performance as compared to either parameter used independently. These findings suggest that PCATa, as a noninvasive indicator of coronary inflammation, when combined with conventional clinical parameters, may offer a more comprehensive assessment of INOCA risk in T2DM patients. The combined use of multiple high-risk indicators appears to enhance the diagnostic accuracy. Interestingly, during data analysis, we observed that the INOCA group exhibited significantly lower lipid-related indices and BMI than the non-INOCA group (P < 0.05). Further analysis revealed a negative association between elevated lipid levels and lower BMI with the occurrence of INOCA. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the higher prevalence of statin use in the INOCA group, which may have influenced the lipid metabolism and contributed to the observed findings[32].

Although the present study demonstrates the potential value of PCATa in identifying INOCA among patients with T2DM, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, this was a single-center retrospective study without external validation. Despite rigorous design, inherent limitations remain, and future studies are warranted to include multicenter cohorts with external validation to strengthen generalizability. Second, PCATa was measured only in the proximal segments of the three main coronary arteries, and correction was applied only for tube voltage without accounting for the potential influence of reconstruction algorithms, which may not fully capture regional heterogeneity in perivascular inflammation. Third, this study primarily focused on total plaque volume without detailed analysis of plaque characteristics, such as peri-plaque PCATa, plaque composition, or vulnerability features. Although prior studies suggest that peri-plaque PCATa may be more sensitive for detecting focal coronary inflammation, most INOCA patients in our cohort had no visible plaques or only a low plaque burden, which limited the feasibility and reliability of plaque-specific analyses. Fourth, our ROC analysis revealed good diagnostic performance of PCATa; however, the derived cutoff values remain unvalidated in an independent external cohort, which limits their current clinical applicability. Future studies should validate these cutoff values in independent external cohorts to improve their clinical applicability. Fifth, assessing the incremental value of PCATa over traditional biomarkers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and coronary flow reserve, would further improve translational relevance; however, such data were not routinely available in our study due to limited laboratory and echocardiographic testing.

Our study found that PCATa has a significant value in identifying the risk of INOCA among T2DM patients. The integration of PCATa with conventional clinical indicators further enhanced the diagnostic performance. These findings may assist clinicians in the early identification of high-risk INOCA patients in the T2DM population and support more timely and targeted clinical management decisions.

| 1. | Low Wang CC, Hess CN, Hiatt WR, Goldfine AB. Clinical Update: Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Mechanisms, Management, and Clinical Considerations. Circulation. 2016;133:2459-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 800] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Y, Dai L, Dong Y, Ma C, Cheng P, Jiang C, Liao H, Li Y, Wang X, Xu X. Coronary inflammation based on pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation in type 2 diabetic mellitus: effect of diabetes management. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McKay GJ, Teo BW, Zheng YF, Sambamoorthi U, Sabanayagam C. Diabetic Microvascular Complications: Novel Risk Factors, Biomarkers, and Risk Prediction Models. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2172106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri HV, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:255-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1670] [Cited by in RCA: 2770] [Article Influence: 554.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beller E, Meinel FG, Schoeppe F, Kunz WG, Thierfelder KM, Hausleiter J, Bamberg F, Schoepf UJ, Hoffmann VS. Predictive value of coronary computed tomography angiography in asymptomatic individuals with diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018;12:320-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association. 11. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S151-S167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Chan K, Wahome E, Tsiachristas A, Antonopoulos AS, Patel P, Lyasheva M, Kingham L, West H, Oikonomou EK, Volpe L, Mavrogiannis MC, Nicol E, Mittal TK, Halborg T, Kotronias RA, Adlam D, Modi B, Rodrigues J, Screaton N, Kardos A, Greenwood JP, Sabharwal N, De Maria GL, Munir S, McAlindon E, Sohan Y, Tomlins P, Siddique M, Kelion A, Shirodaria C, Pugliese F, Petersen SE, Blankstein R, Desai M, Gersh BJ, Achenbach S, Libby P, Neubauer S, Channon KM, Deanfield J, Antoniades C; ORFAN Consortium. Inflammatory risk and cardiovascular events in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: the ORFAN multicentre, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2024;403:2606-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 75.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Radico F, Zimarino M, Fulgenzi F, Ricci F, Di Nicola M, Jespersen L, Chang SM, Humphries KH, Marzilli M, De Caterina R. Determinants of long-term clinical outcomes in patients with angina but without obstructive coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2135-2146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Biesenbach IIA, Heinsen LJ, Overgaard KS, Andersen TR, Auscher S, Egstrup K. The Effect of Clinically Indicated Liraglutide on Pericoronary Adipose Tissue in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Cardiovasc Ther. 2023;2023:5126825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oikonomou EK, Marwan M, Desai MY, Mancio J, Alashi A, Hutt Centeno E, Thomas S, Herdman L, Kotanidis CP, Thomas KE, Griffin BP, Flamm SD, Antonopoulos AS, Shirodaria C, Sabharwal N, Deanfield J, Neubauer S, Hopewell JC, Channon KM, Achenbach S, Antoniades C. Non-invasive detection of coronary inflammation using computed tomography and prediction of residual cardiovascular risk (the CRISP CT study): a post-hoc analysis of prospective outcome data. Lancet. 2018;392:929-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 852] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li N, Dong X, Zhu C, Shi Z, Pan H, Wang S, Chen Y, Wang W, Zhang T. Association study of NAFLD with pericoronary adipose tissue and pericardial adipose tissue: Diagnosis of stable CAD patients with NAFLD based on radiomic features. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025;35:103678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Goeller M, Achenbach S, Herrmann N, Bittner DO, Kilian T, Dey D, Raaz-Schrauder D, Marwan M. Pericoronary adipose tissue CT attenuation and its association with serum levels of atherosclerosis-relevant inflammatory mediators, coronary calcification and major adverse cardiac events. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021;15:449-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Marx N, Federici M, Schütt K, Müller-Wieland D, Ajjan RA, Antunes MJ, Christodorescu RM, Crawford C, Di Angelantonio E, Eliasson B, Espinola-Klein C, Fauchier L, Halle M, Herrington WG, Kautzky-Willer A, Lambrinou E, Lesiak M, Lettino M, McGuire DK, Mullens W, Rocca B, Sattar N; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:4043-4140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 999] [Cited by in RCA: 888] [Article Influence: 296.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beltrame JF, Tavella R, Jones D, Zeitz C. Management of ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). BMJ. 2021;375:e060602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang H, Teng H, Luo P, Fu R, Wang X, Qin G, Gao M, Ren J. The role of left ventricular hypertrophy measured by echocardiography in screening patients with ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;39:1657-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oikonomou EK, Desai MY, Marwan M, Kotanidis CP, Antonopoulos AS, Schottlander D, Channon KM, Neubauer S, Achenbach S, Antoniades C. Perivascular Fat Attenuation Index Stratifies Cardiac Risk Associated With High-Risk Plaques in the CRISP-CT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:755-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma R, van Assen M, Ties D, Pelgrim GJ, van Dijk R, Sidorenkov G, van Ooijen PMA, van der Harst P, Vliegenthart R. Focal pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation is related to plaque presence, plaque type, and stenosis severity in coronary CTA. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:7251-7261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Kazerooni EA, Narula J, Yankelevitz D, Abbara S. 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: A report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11:74-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Azour L, Kadoch MA, Ward TJ, Eber CD, Jacobi AH. Estimation of cardiovascular risk on routine chest CT: Ordinal coronary artery calcium scoring as an accurate predictor of Agatston score ranges. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu Q, Qiu J, Sun S, Wang X, Sun Z, Zhao H. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for moderate-high risk asymptomatic type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:974294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, Rossello X, Adamo M, Ainslie J, Banning AP, Budaj A, Buechel RR, Chiariello GA, Chieffo A, Christodorescu RM, Deaton C, Doenst T, Jones HW, Kunadian V, Mehilli J, Milojevic M, Piek JJ, Pugliese F, Rubboli A, Semb AG, Senior R, Ten Berg JM, Van Belle E, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Vidal-Perez R, Winther S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3415-3537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1612] [Cited by in RCA: 1334] [Article Influence: 667.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Szolc P, Guzik B, Niewiara Ł, Kleczyński P, Bernacik A, Diachyshyn M, Stąpór M, Żmudka K, Legutko J. Tailored treatment of specific diagnosis improves symptoms and quality of life in patients with myocardial Ischemia and Non-obstructive Coronary Arteries. Sci Rep. 2025;15:18968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fu B, Wei X, Lin Y, Chen J, Yu D. Pathophysiologic Basis and Diagnostic Approaches for Ischemia With Non-obstructive Coronary Arteries: A Literature Review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:731059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mehta PK, Huang J, Levit RD, Malas W, Waheed N, Bairey Merz CN. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA): A narrative review. Atherosclerosis. 2022;363:8-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dai X, Yu L, Lu Z, Shen C, Tao X, Zhang J. Serial change of perivascular fat attenuation index after statin treatment: Insights from a coronary CT angiography follow-up study. Int J Cardiol. 2020;319:144-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Çakar M, Balta Ş, Şarlak H, Akhan M, Demirkol S, Karaman M, Ay SA, Kurt Ö, Çayci T, İnal S, Demirbaş Ş. Arterial stiffness and endothelial inflammation in prediabetes and newly diagnosed diabetes patients. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2015;59:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu Y, Sun Y, Hu C, Liu J, Gao A, Han H, Chai M, Zhang J, Zhou Y, Zhao Y. Perivascular Adipose Tissue as an Indication, Contributor to, and Therapeutic Target for Atherosclerosis. Front Physiol. 2020;11:615503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lin A, Dey D, Wong DTL, Nerlekar N. Perivascular Adipose Tissue and Coronary Atherosclerosis: from Biology to Imaging Phenotyping. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2019;21:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Antonopoulos AS, Sanna F, Sabharwal N, Thomas S, Oikonomou EK, Herdman L, Margaritis M, Shirodaria C, Kampoli AM, Akoumianakis I, Petrou M, Sayeed R, Krasopoulos G, Psarros C, Ciccone P, Brophy CM, Digby J, Kelion A, Uberoi R, Anthony S, Alexopoulos N, Tousoulis D, Achenbach S, Neubauer S, Channon KM, Antoniades C. Detecting human coronary inflammation by imaging perivascular fat. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal2658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Eringa EC, Serne EH, Meijer RI, Schalkwijk CG, Houben AJ, Stehouwer CD, Smulders YM, van Hinsbergh VW. Endothelial dysfunction in (pre)diabetes: characteristics, causative mechanisms and pathogenic role in type 2 diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:39-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Patel N, Greene N, Guynn N, Sharma A, Toleva O, Mehta PK. Ischemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease: more than meets the eye. Climacteric. 2024;27:22-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sheng X, Murphy MJ, MacDonald TM, Wei L. Effect of statins on total cholesterol concentrations and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1201-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/