Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111954

Revised: August 4, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 185 Days and 13.6 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has rapidly become the leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis worldwide, driven by the global surge in metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. In parallel, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HF

Core Tip: The ever-changing terminology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to encompass metabolic dysfunction truly reflects its systemic impact beyond the liver. Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of MASLD-related morbidity and mortality. Amongst the various cardiovascular diseases linked to MASLD, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is most closely related to MASLD, sharing a pathophysiologic foundation with MASLD and rooted in common metabolic risk factors. This review explores the intertwined mechanisms linking MASLD and HFpEF, highlighting their clinical convergence and therapeutic relevance.

- Citation: Brar AS, Khanna T, Sohal A, Hatwal J, Sharma V, Singh C, Batta A, Chandra P, Mohan B. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A state-of-the-art review. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 111954

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/111954.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.111954

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has been on the rise and has now become one of the leading causes of liver transplantation in the United States. The new nomenclature requires at least one of the five metabolic risk factors along with liver steatosis to diagnose MASLD and metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). These include diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL levels[1,2]. The shared risk factors that can predispose patients to MASLD and MASH have been implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). As a result, there have been studies aiming to estimate whether MASLD is a risk factor for CVD development. In a study by Simon et al[3], the risk of developing cardiovascular outcomes was significantly higher among patients with MASLD. The risk was independent of the common cardiometabolic risk factors shared by MASLD and CVD. Studies by Mantovani et al[4] and Simon et al[3] reported that MASLD was associated with an increased risk of developing CVD, independent of common cardiometabolic risk factors. In both studies, the risk was progressively higher in patients with non-cirrhotic fibrosis and cirrhosis[4]. CVD has also been reported to be the leading cause of mortality among patients with MASLD. A systematic review by Younossi et al[5] reported the all-cause mortality to be 12.6 per 1000 person-years. In their analysis, cardiac-specific mortality was noted to be 4.2 per 1000 person-years, while chronic liver disease-specific mortality was 0.92 per 1000 persons.

The common CVDs noted among patients with MASH are atherosclerosis, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and heart failure, especially heart failure with preserved ejection[5]. There is a well-established bidirectional relationship between liver disease and heart failure. Heart failure can lead to congestive hepatopathy, while the presence of advanced fibrosis can result in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. A recent 7-year cohort study found that MASLD was associated with diastolic dysfunction independent of other risk factors. A meta-analysis has also supported these findings[6]. Studies have also reported diastolic dysfunction to be related to the degree of liver fibrosis[7,8]. As there is new emerging evidence that suggests that the presence of MASLD/MASH, even without advanced fibrosis, can increase the risk of developing heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), our article aims to review the current epidemiology, pathogenesis, cellular mechanisms, as well as the impact of various therapies on MASLD on HFpEF.

Female sex hormones are well known to not only protect against CVD in pre-menopausal females but also contribute to improved adipose tissue function and preventing its systemic deposition.

Prior longitudinal studies and a meta-analysis have found that cardiac dysfunction consistent with HFpEF is commonly seen in MASLD patients[9]. Independent associations between MASLD and structural cardiac changes have been observed, including left atrial (LA) size, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), and strain[10-12]. Furthermore, biological sex plays a role in the association of MASLD and HFpEF due to the protective role of estrogen in CVD and difference in ectopic adipose deposition trends[13]. Echocardiography in MASLD patients has shown impaired LV relaxation and diastolic dysfunction. Doppler imaging in these patients has shown lower E wave and e’ velocity, decreased E/a ratio, and increased E/e.’ Overall, this suggests that MASLD patients tend to have higher LV filling pressure even after adjusting for comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity[14]. However, another longitudinal study found that the association of MASLD with LV hypertrophy (LVH) was not significant after controlling for obesity[11]. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based study tested for correlates of diastolic dysfunction and found that it was associated with hepatic steatosis and visceral obesity despite not showing a significant relation with myocardial triglycerides[15].

Multiple studies have aimed to establish the relationship between MASLD and heart failure. A recent meta-analysis by Qiu et al[16] examining 6 cohort studies containing 10979967 participants reported patients with MASLD at a 36% higher risk of incident HF than patients without MASLD. The increased risk was also noted among patients with mild steatosis. Regarding the risk of HFpEF among patients with MASLD, a study by Fudim et al[17] evaluating 870535 Medicare beneficiaries reported the presence of MASLD to be associated with a significantly increased risk of developing new onset HF. Their study reported a higher risk of developing HFpEF compared to the risk of HFrEF.

Single-center studies provide information regarding the prevalence of fatty liver among patients with HFpEF. In a study by Miller et al[18] evaluating 181 patients with HFpEF, 49 (27%) patients had MASLD. Twelve patients had imaging results consistent with cirrhosis. Notably, only 96 of the patients had abdominal imaging in the study, and among these patients, the prevalence of MASLD and cirrhosis was 50% and 11.5%, respectively. When including patients who had imaging or NFS scores consistent with cirrhosis, the prevalence was noted to be 48.6%. Their study also indicated that patients with fatty liver on imaging had more severe heart failure. Another survey by Wegermann et al[19] indicated that among 89 patients with biopsy-proven MASLD, the prevalence of HFpEF and diastolic dysfunction was 41.9% and 47.2%, respectively. A study by Minhas et al[20] utilizing United States national hospitalization data noted that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)'s prevalence was 2.3% among patients with HFpEF. This study might underestimate the prevalence as it was based on International Classification of Diseases-10 codes, and information regarding more granular data was missing. Despite this limitation, this study is of interest because MASLD was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital complications among patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction[20]. Studies have established that the presence and extent of fibrosis in MASLD correlates with the prognosis of HFpEF[9,19,21,22]. More severe fibrosis, i.e., F3-F4, has shown associations with worse cardiovascular outcomes[23]. Worse diastolic function and greater LA diameter have been observed in MASLD patients with advanced fibrosis[18]. The association has remained true for patients hospitalized with decompensated HFpEF[24]. The significant effect of MASH on HFpEF prognosis supports the conjecture that the two diseases might progress via similar pathogenetic pathways. Thus, it is essential to understand the shared risk factors and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for developing these conditions.

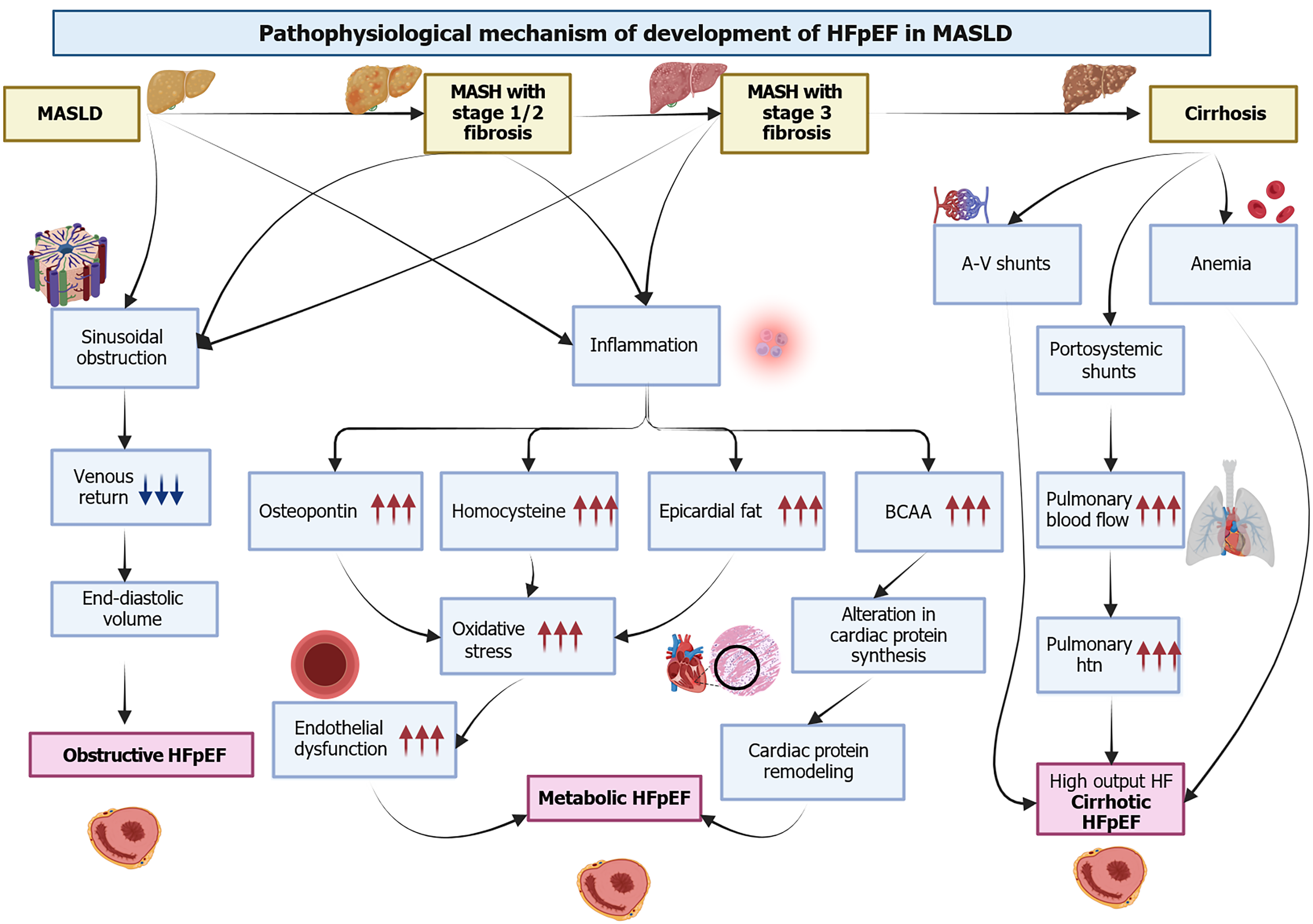

HFpEF is characterized by diastolic and systolic reserve abnormalities, pulmonary hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and reserve failure[25]. Initially, HFpEF was studied as a unified syndrome; however, due to the differences in the underlying mechanisms, several subtypes of this disease have since been discussed. A previous study by Salah et al[9] reported that three significant phenotypes among patients with MASLD include obstructive, metabolic, and cirrhosis HFpEF phenotypes. Understanding these phenotypes is beneficial, as this can provide insight into the various ways by which MASLD/MASH can predispose to HFpEF development. Figure 1 highlights the pathophysiological mechanism of HFpEF development in MASLD.

The liver is a major metabolic organ; about 25% of blood volume passes through the liver before reaching the heart. In the early stages of MASLD, there is an increased resistance in the hepatic sinusoids, which may impede venous return. As fibrosis progresses, the resistance in the hepatic sinusoids may increase, further impeding the venous return[26]. Fibrosis may reduce preload, which impairs the peak oxygen consumption observed among patients with MASLD[27].

Several metabolic and inflammatory abnormalities, such as insulin resistance (IR), visceral adiposity, endothelial dysfunction, and dyslipidemia, have been linked to the development of HFpEF and MASLD. It has been hypothesized that increased inflammation in patients with MASLD may predispose them to the development of metabolic HFpEF[28]. As the history of the disease progresses from steatosis to inflammation and advanced fibrosis, studies have noted an increase in the production of increased systemic proinflammatory markers, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and chemokine ligand 3[29]. The increase in systemic inflammation can result in endothelial dysfunction, thus predisposing the patient to HFpEF[30].

Osteopontin has been suggested to play an essential role in inflammation, extracellular deposition, and fibrosis. Studies have reported osteopontin to be increased in MASLD, especially in those with advanced fibrosis[31]. It has been hypothesized that increased osteopontin may directly or indirectly increase the risk of HFpEF. A study reported that increased osteopontin levels among patients with HFpEF might predispose them to higher severity of HF symptoms[32]. Other markers of inflammation, such as asymmetrical dimethylarginine and homocysteine levels, are increased in patients with MASLD. These markers can enhance oxidative stress and platelet dysfunction[33].

Circulating branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) levels have also been increased among patients with MASLD. Increased BCAA exposure may activate cardiac protein synthesis, resulting in cardiac structural changes[34]. The presence of MASLD can also result in cardiac metabolic remodeling, which may even precede the structural remodeling seen in the advanced stages of the disease[35]. A previous study of 55 individuals noted a correlation between the presence of fat in the liver and myocardial IR[36]. Another study reported increased epicardial fat among patients with hepatic steatosis[35].

An additional HFpEF phenotype has been described among patients with advanced cirrhosis. Portal hypertension, a complication of cirrhosis, leads to the development of portosystemic shunts[36,37]. These shunts may increase pulmonary flow and result in the transit of vasoactive mediators from splanchnic circulation to the pulmonary system. This may result in the remodeling of pulmonary vasculature and pulmonary hypertension[38]. It has been suggested that micro-shunts may develop earlier during MASLD, leading to hemodynamic changes[39].

Patients with cirrhosis can also develop A-V shunts in the pulmonary and peripheral circulation[39]. The hemodyna

The five prominent risk factors that play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of both MASLD and HFpEF are obesity (visceral adiposity), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (Figure 2).

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) increases both the risk and the morbidity associated with HFpEF and diabetic cardiomyopathy, conditions characterized by myocardial alterations that occur independently of hypertension and coronary artery disease. This association is well established[25,41-43]. The effects on the myocardium include hypertrophy, stiffness, and interstitial fibrosis, leading to diastolic compromise[44,45]. It is reported that up to 90% of T2DM patients develop MASLD, and MASLD is thrice as common in people with T2DM than those without[46]. Furthermore, T2DM is associated with obesity, indicative of a positive energy balance that takes a considerable toll on the liver, the main organ responsible for metabolism[46]. Fatty acid deposition in the liver does not end with steatosis; the high levels of circulating FAs also induce a pro-inflammatory state. Intermediates generated during lipid metabolism, such as ceramides and diacylglycerols (DAG), are lipotoxic and activate Kuppfer cells, which produce cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α. These signals further recruit stellate cells, promoting fibrosis and perpetuating a vicious cycle between fatty liver disease and T2DM[47]. Adiponectin reduces Toll-like receptor four signaling, reduces the production of TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and IL-6, and increases the generation of anti-inflammatory IL-10, thereby suppressing inflammatory pathways[48].

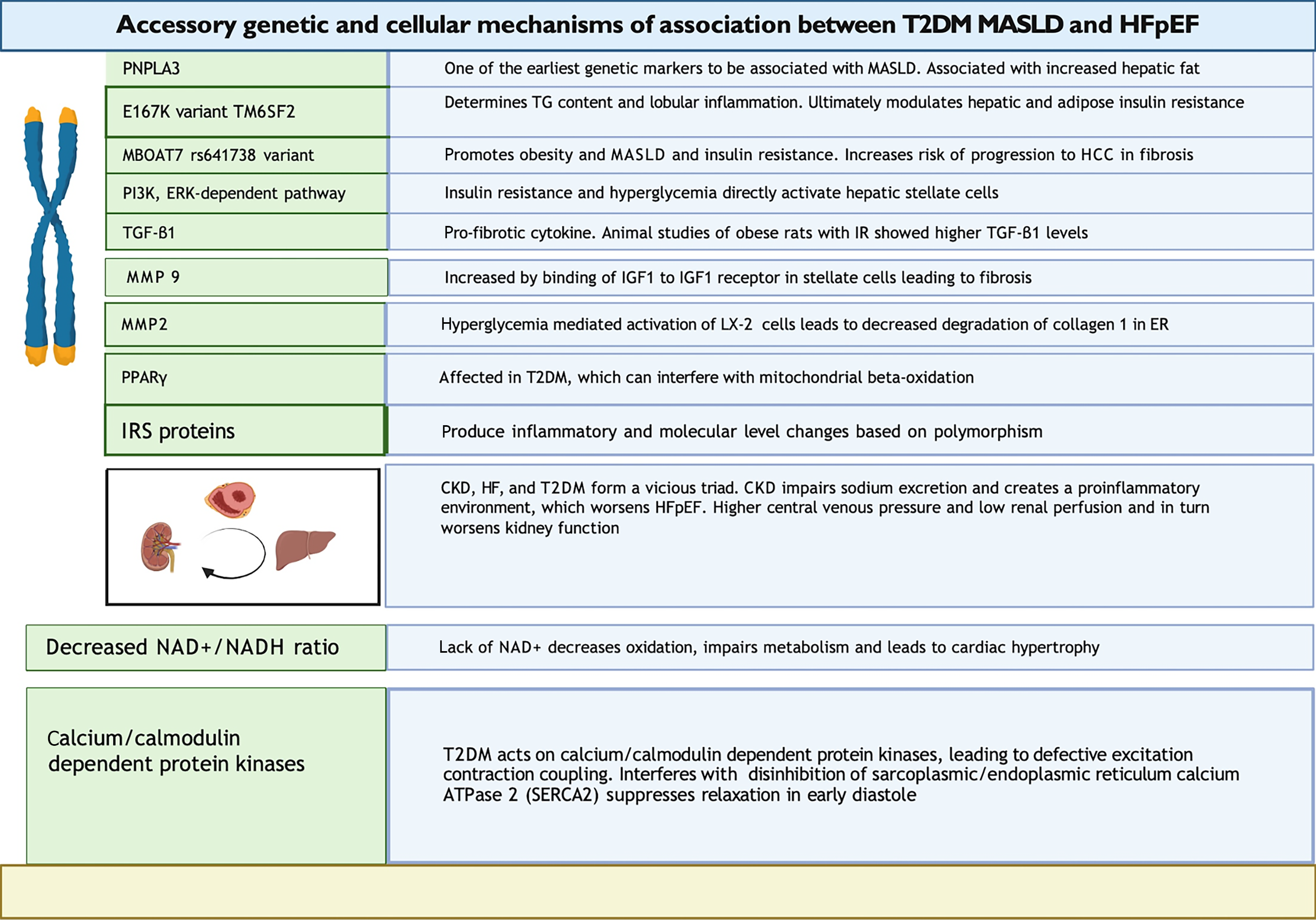

Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of HFpEF in T2DM. IR in T2DM impairs endothelial nitric oxide (NO) generation. Reduced NO and lower cGMP-PKG signaling activity impair vasodilation and make arteries and cardiomyocytes stiffer[49]. HFpEF patients are commonly plagued by endothelial dysfunction. Vascular stiffness impairs diastolic reserve, contributing to ventricular vascular uncoupling, which is almost ubiquitous in HFpEF[50]. Arterial stiffness affects preload and afterload, destabilizing stroke volume and blood pressure in HFpEF patients. Hyperglycemia in T2DM leads to the deposition of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), resulting in concentric LV remodeling, wall stiffness, and slow LV relaxation[25,46]. AGEs promote inflammatory damage resulting in cell death[51]. Inappropriate protein glycosylation in the myocardium leads to interstitial fibrosis, worse compliance, and HFpEF[52]. The ensuing lipid toxicity, TG deposition, microvascular damage, endothelial injury, and coronary circulatory compromise culminate in diastolic function[43,53]. Epicardial fat deposition puts mechanical stress on the pericardium, causing diastolic dysfunction[52]. Similarly, elevated lipid levels affect the liver. T2DM patients exhibit IR, leading to increased peripheral fat breakdown and entry of free fatty acids into the liver[54]. Paradoxically, lipogenesis can also increase IR, conceivably attributable to ER stress and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation. Downstream lipogenesis enzymes are activated, increasing fatty acid production[55]. While fatty acid synthesis is increased, beta-oxidation is impaired due to IR, culminating in increased steatosis[48]. Figure 3 highlights the critical accessory genetic and cellular association mechanisms between T2DM, MASLD, and HFpEF.

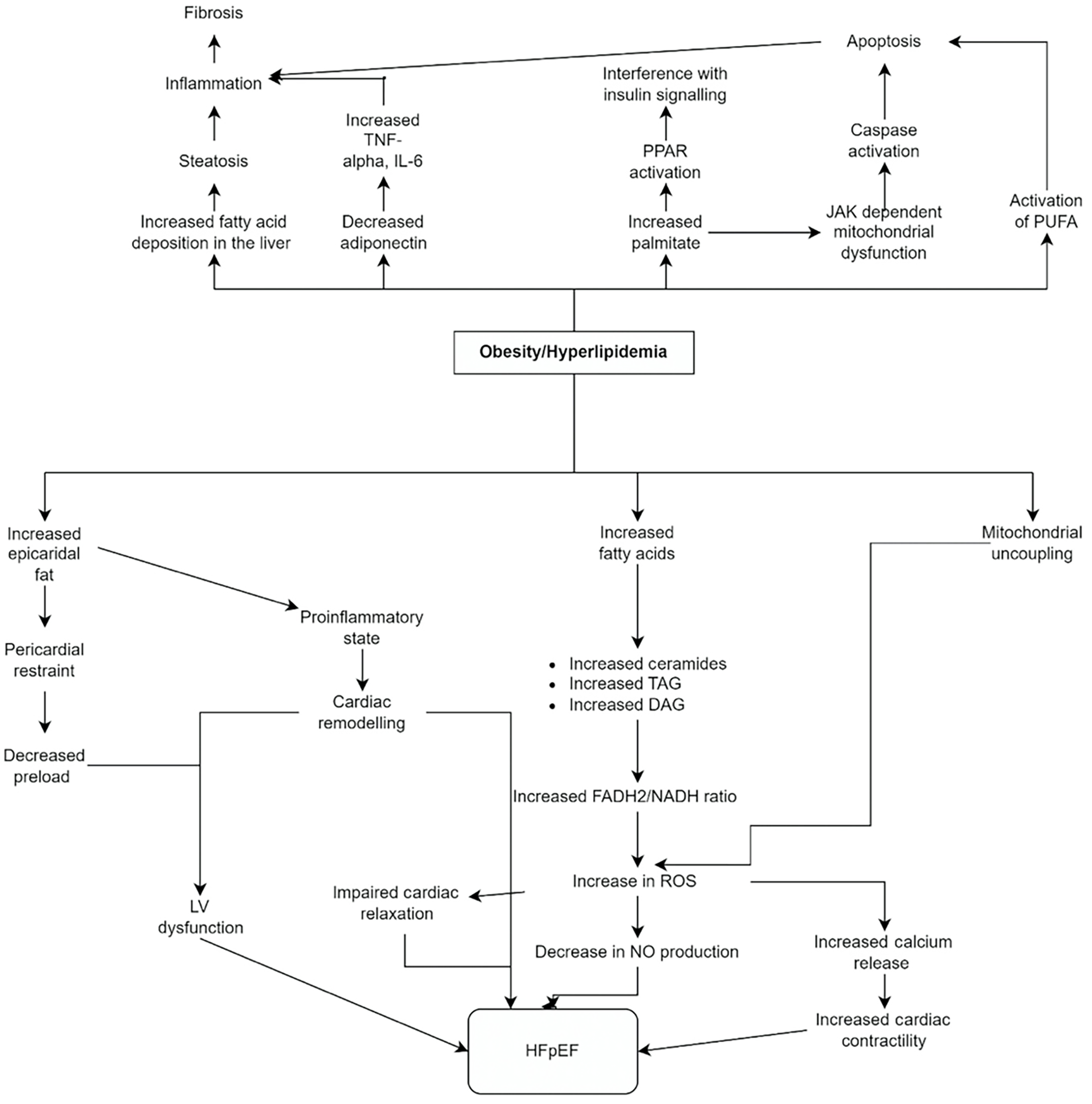

Obesity contributes to both HFpEF and MASLD. Obesity-driven increase in de novo lipogenesis propagates HFpEF primarily by creating a pro-inflammatory state and deposition of epicardial fat[52,56-58]. Obesity and weight gain propagate diastolic dysfunction attributed to reduced systolic reserve, and visceral adipose tissue exhibits a firmer linkage with concentric remodeling[59,60]. The role of epicardial adipose tissue, which is strongly correlated with body mass index (BMI), in HFpEF has been well studied and involves both mechanical and inflammatory effects[61]. Epicardial fat increases pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) at rest by uncoupling LV filling pressure (PCWP) and LV pre-load (end-diastolic volume)[62]. It raises intracavitary pressure, underestimating brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, and contributes to counterproductive interactions between the heart and pericardium, creating a diagnostic conundrum[63]. Additionally, epicardial fat contributes to inflammation by increasing the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, contributing to cardiac muscle mitochondrial dysfunction[64]. Meanwhile, anti-inflammatory cytokines like adiponectin are reduced in obesity. Higher levels of epicardial adipose tissue in HFpEF have been associated with worse hemodynamics, poor right ventricle-pulmonary artery coupling, LV fibrosis, decreased exercise capacity, and higher hospitalization and mortality rates[61]. Lipotoxicity does not spare the myocardium. As fatty acids increase in circulation, they are increasingly taken up by the myocardium. This leads to higher levels of long-chain fatty acyl CoA intracellularly and higher synthesis of ceramides, triacylglycerol, and DAG[65], When the heart relies more on adipose than glucose to fulfill its energy needs, it shifts towards increased Flavin adenine dinucleotide hydride-2/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrogen ratio, less efficient energy generation, and greater production of reactive oxygen radicals[56]. While the energy production using fat is less efficient, the energy demand of the adipose-riddled myocardium is higher. This is proposed to contribute to HFpEF because impaired ATP metabolism initially affects the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium ATPase to lower cytosolic Ca2+ during diastole, thereby interfering with relaxation[57,66].

Similarly, obesity contributes to the development of hepatic steatosis, as well as its progression to hepatitis and cirrhosis[67]. Furthermore, hepatic steatosis has been demonstrated as a risk factor for ischemic heart disease in mouse models[68]. It is theorized that when the level of circulating free fatty acids is high enough to overwhelm adipose tissue, hepatocytes must take over and store the excessive triglycerides[69]. If the patient has concurrent T2DM and IR, increased lipolysis further propagates this effect[69]. Both lipotoxicity and glucotoxicity contribute to obesity-related MASH. Insulin-resistant adipocytes release excessive free fatty acids, promoting inflammation and hepatic lipid deposition. Meanwhile, hepatocytes are unable to dispose of the accumulated fat, resulting in hepatic steatosis[70]. Lipid-laden hepatocytes initiate a pro-inflammatory arc, activating Kupffer, dendritic, and hepatic stellate cells. Neutrophils, T-lymphocytes, and macrophages further invade the liver[71]. The inflammatory cascade attempts to heal injured hepatocytes by recruiting stellate cells, activated endothelial cells, and myofibroblasts[72]. However, the injury tends to overwhelm the healing capacity, and the inflammatory process culminates in scarring and even neoplasia[73]. Additionally, animal models have demonstrated associations between cardiac steatosis and transcription factor Forkhead box protein O1,109, which has recently been designated a cellular mechanism involved in HFpEF[74].

Meanwhile, obesity disrupts the balanced adipokine profile seen in healthy individuals. Adipose hypertrophy promotes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines[75]. While some adipokines, such as adiponectin and obestatin, have protective effects on the liver, others, including TNF-α, IL-6, chemerin, retinol-binding protein-4, and resistin, exacerbate steatosis and hepatitis[75]. Adiponectin exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by decreasing pro-inflammatory and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines. Patients with hepatic steatosis show lower adiponectin levels than healthy controls, while those with steatohepatitis show even lower levels. Counterintuitively, patients who have progressed to cirrhosis display higher levels of adiponectin, which could represent impaired clearance or an attempt to salvage the hepatic injury[76,77]. Figure 4 depicts the vital pathophysiological mechanisms by which obesity/hyperlipidemia contributes to the risk of developing MASLD and HFpEF.

Another common risk factor between HFpEF and MASLD is hypertension. Hypertension is a well-known risk factor for HF development, including HFpEF[77]. The rise in blood pressure from an ideal baseline is proportional to LVH, even starting from pre-hypertensive range pressures[78]. In hypertensive patients, the LV must constantly pump against an increased afterload. In line with Laplace’s Law, the increased work causes LV to undergo pathological hypertrophy and fibrosis, contributing significantly to diastolic dysfunction. Hypertensive patients who develop LVH are at high risk of developing HF in the future. A study demonstrated that every 1% increase in LV mass above baseline was associated with a 1% higher risk of HF[78].

MASLD has been reported to be present in 30% of hypertensive patients[79,80]. Recent studies have suggested a bidirectional relationship between the two. While the presence and value of hypertension have been shown to predict MASLD, the presence of MASLD can also serve as a predictor for hypertension[81]. Additionally, concomitant hypertension is associated with greater odds of MASLD progression to fibrosis[82]. Even in normotensive patients, higher BP can predict hepatic fibrosis[83]. A cohort study of Nagasaki nuclear bomb survivors found that hypertension predicted the development of MASLD over time[84]. A study in China found that hypertension was a significant factor in predicting MASLD, though less than obesity and dyslipidemia[84]. One of the explanations for this correlation is based on the Renin Angiotensin Activating System (RAAS). Animal models have helped confirm the role of RAAS in developing both hepatic fibrosis and hypertension[85]. Specific mutations in angiotensinogen and its receptors have been associated with MASLD[82].

Lipotoxicity has undoubtedly been implicated in HFpEF pathogenesis[86]. In HFpEF, increased fatty acid oxidation leads to greater cardiac uptake of fatty acids and myocardial lipid deposition[87,88]. A cardiac MRI study found 2.3 times higher lipid content in the myocardium compared to controls[89]. Inactivation of adipose triglyceride lipase also reduces lipolysis, increases lipid deposits in the heart, and worsens diastolic function[65]. Excessive acyl CoA synthase activity increases triglyceride accumulation and is associated with concentric LVH[65]. Toxicity is likely a consequence of DAGs and ceramides than triglycerides. Activating DAG kinases that decrease DAG levels has been associated with improved cardiac function[90]. Inhibiting ceramide synthesis has also led to improvements in cardiac activity, as seen in imaging[91]. In mice that lack malonyl-CoA decarboxylase, a fatty diet did not lead to cardiac dysfunction, possibly due to low levels of acylcarnitines, i.e. toxic lipid intermediaries[92].

DAGs and ceramides upregulate NADPH oxidase and form reactive oxygen species (ROS). One of the mechanisms of ROS-induced damage is NO depletion. In HFpEF, myocardial tissue shows increased nitrotyrosine staining, indicating diversion of NO toward peroxynitrite formation. The resulting decrease in NO availability likely contributes to diastolic dysfunction[93]. ROS also acts on the ryanodine receptor to increase calcium release, which could contribute to increased passive cardiac muscle tension[94]. ROS can also activate pro-fibrotic pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK[95]. Lipotoxic effects on the heart can induce mitochondrial abnormalities, including mitochondrial uncoupling[96]. Overall, multimodal pathogenesis links hyperlipidemia and HFpEF.

Higher triglyceride levels are also associated with MASLD, even in the non-obese population[97]. As in obesity, high amounts of circulating lipids tend to get deposited in hepatocytes[98]. Fat deposition makes the liver more vulnerable to inflammation-mediated injury and impairs its regenerative capacity. The effect of increased hepatocyte exposure to fatty acids has been evaluated in in vitro models. Hepatocytes exposed to high levels of palmitate and oleate show increased expression of FAT/CD36 and fatty acid transport protein MRI-2, leading to intracellular accumulation of DAG and ceramides[99]. Moreover, oleate has been associated with steatosis and palmitate has been associated with apoptosis in in vitro studies[100]. Lipophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is a lipid subgroup that induces leukocyte chemotaxis. Both patients and animal models of MASLD have shown high LPC levels. LPC is theorized to promote apoptosis by activating pathways involving transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding homologous protein. This upregulates pro-apoptotic proteins such as p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis. Ceramide levels are also high in MASLD patients. They interact with TNF-α and increase ROS generation, resulting in inflammation and apoptosis[101]. They have also been associated with IR[102].

Studies on the mechanisms of hepatocyte apoptosis in lipotoxicity have implicated both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Intrinsic pathways are activated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, ROS, and altered mitochondrial permeability. ER stress is involved in the steatosis to hepatitis progression[100]. XBP1 and eIF2α are ER stress-sensing pathways that also regulate lipid metabolism. The change from steatosis to MASH involves upregulating pro-apoptotic genes and downregulating ER stress pathway genes. The Fas ligand initiates extrinsic pathways[103].

MASLD pathogenesis in OSA largely centers around chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH)[104]. The stress of CIH leads to the release of ROS and inflammatory mediators, which contribute to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis[105]. One factor that mediates this effect is HIF-1α. HIF-1α is increased in OSA and MASLD through oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury[106,107]. HIF-1α influences the release of lysyl oxidase (LOX), which plays a role in extracellular matrix protein cross-linking and promotes fibrosis[108]. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that LOX levels are higher in patients with hepatic fibrosis[109]. In animal models, HIF-1α deletion has been associated with reduced expression of genes promoting lipogenesis and reduced fibrosis[110]. HIF-2 is also implicated and results in dysregulated lipid metabolism, which leads to severe hepatic steatosis[111]. Generally, prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes degrade HIFs. Hypoxia results in decreased PHD activity, enabling excessive HIF activity and consequent liver injury[112]. The use of HIF-1α inhibitors has been observed to improve liver fibrosis[113]. Oxidative injury damages DNA, lipids, and proteins. The resultant inflammation triggers Kupffer cells and stellate cells to promote fibrosis. Hypoxia also activates NF-κB, increasing TNF-α and IL-6 to trigger hepatic injury[114]. The hypoxia from OSA purportedly alters intestinal mucosal permeability, upregulates TLR-4 expression in the liver, and affects the gut microbiome, all of which play a role in MASLD[115]. OSA impacts sleep quality, and prior studies have linked low sleep duration with MASLD[116]. This is partially explained by the role of circadian rhythms in regulating insulin and lipid metabolism, the disturbance of which could promote inflammation and liver disease[117].

Endothelial dysfunction also serves as a connecting link between OSA and HFpEF. OSA patients show reduced nitrite concentrations in plasma and impaired vasodilation. ROS activate NF-κB to increase the production of C-reactive protein, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and vascular and intracellular adhesion molecules, which cause endothelial injury, atherosclerosis, and HF. Inflammation also generates transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), which lays down the fibrotic matrix and further impairs LV diastolic function[118]. ROS generation in OSA contributes to cell injury and death[119]. A systematic review by Polecka et al[120] found that HFpEF patients with concomitant OSA showed higher BNP levels than those without OSA[120]. Moreover, BNP levels decrease in OSA patients upon positive airway pressure treatment[121]. The severity of acute intermittent hypoxia in OSA also correlates with diastolic compromise in HFpEF[121]. Diastolic compromise, measured by isovolumetric relaxation time, is associated with more severe sleep-disordered breathing. Echocardiographic assessment and LA volume index have also been used to confirm the association between OSA and diastolic dysfunction[122]. Moderate and severe OSA show a more reliable association with poor diastolic function than mild OSA[123]. Like BNP levels, echocardiography has been used to assess improved diastolic dysfunction after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure in OSA patients. Overall, OSA and HFpEF share a bidirectional relationship, and treatment of OSA can improve HFpEF[124].

Lifestyle interventions play a crucial role in the management of HFpEF and MFLD. These interventions incorporate calorie restriction, graded physical therapy, and dietary modification. Weight loss significantly impacts IR, visceral obesity, inflammation, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk[125-128].

Weight loss leads to decreased hepatic IR and FFA levels, and an 8% weight loss is sufficient to reverse hepatic IR, while sustained weight loss exceeding 10% reverses fibrosis and portal inflammation[129-132]. BMI correlates with HFpEF incidence in a dose-dependent manner[133]. The benefits of weight loss in HFpEF are attributed to improved myocardial function, microvasculature, chronic inflammation reversal, and hemodynamic status enhancement[134].

The current guidelines from American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology recommend calorie restriction in combination with 150 minutes of aerobic activity per week[125-127]. This regimen has been shown to significantly improve markers of metabolic health, such as blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, and insulin levels[135]. However, maintaining long-term weight loss requires higher levels of physical activity (200-300 minutes/week) as the body responds by lowering its metabolic rate to regain weight. This highlights the importance of bariatric surgery (BS)[132,136-140].

The latest European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) joint evidence-based guidelines recommend a Mediterranean diet for its high of monounsaturated fatty acid and polyunsaturated fatty acid content[127,141,142]. While both the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet and the Mediterranean diet demonstrate efficacy in reducing hypertension, the latter exhibits superior anti-inflammatory properties and reverses the underlying mechanisms of obesity, whereas the former has a greater effect on lowering blood pressure[143-145]. Furthermore, the Mediterranean diet discourages the consumption of processed or high fructose foods and sugary drinks, which contribute to the reduction of AGEs and lower central adiposity[146-150]. A high-protein diet may benefit MASLD due to its anorexigenic properties[151-153]. However, it is crucial to consider the protein source, as red meat consumption increases cardiovascular risk[153].

Physical activity benefits blood pressure independent of weight loss through vasculature modulation and sympathetic activity attenuation[138,154,155]. In conclusion, exercise in combination with a hypocaloric diet improved peak oxygen consumption, yet only exercise has been linked with enhanced quality of life[156-158]. These findings align with current statements by American College of Cardiology[159].

BS may facilitate calorie restriction with a goal of 7%-10% body weight reduction in line with current guidelines[160]. These include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding[161]. In obese patients, BS is correlated with more significant weight loss and reversal rates of T2DM compared with nonsurgical therapy[162]. Furthermore, a greater decrease in glycosylated hemoglobin and a favorable metabolic profile was observed. The beneficial impact of BS in metabolic disease and MASLD is attributed to their effects on dietary patterns, alteration in stomach functioning, gut absorption metrics, gut hormone release, intestinal microbial biodiversity, and bile acid secretion. Accordingly, weight loss attributed to BS has been associated with resolution and improved liver fat content, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis[163]. Resolution/improvement has been seen in 30%-40% of all liver fibrosis patients, highlighting its success[164,165]. Interestingly, it is also associated with a decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[166]. BS decreases the risk of major adverse cardiac events and causes mortality in patients with MASLD and obesity[167].

Furthermore, BS is robustly aligned with improved cardiac functioning and relaxation due to improvements in hemodynamics, inflammation, and a favorable metabolic profile128. This is attributed to improved diastolic function and cardiac geometry. As a result, markers implicated in HFpEF, such as LA diameter, LV mass index, and LV mass, improve in patients undergoing BS[168].

Metformin is a biguanide widely used in T2DM patients because of its safety and efficacy, and it is often prescribed to overweight patients[169]. Metformin is usually the initial therapy in diabetic patients and benefits patients with stage B HFpEF through reversal of diastolic dysfunction, as its use is closely correlated with decreased LV mass index and improved ejection fraction[170,171].

While EASL-EASO-EASD and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) do not recommend the use of metformin in MASLD, there are still benefits to its use in this population in terms of its effects on determinants such as obesity, T2DM, and dyslipidemia[127,172]. Metformin use demonstrates a significant decrease in liver enzymes and displays a modest, nonsignificant association with reduced steatosis or lobular inflammation, irrespective of diabetic status. However, it has no effect on fibrosis[173-177].

Metformin use has a protective effect on HFpEF incidence and progression through its action on skeletal muscles, liver, gut, heart, and vasculature[178]. Its protective effect on the heart is attributed to improved glycemic control, protection against hyperinsulinemia, and reduction of oxidative stress by halting titin-mediated cardiac hypertrophy and action at the eNOS pathway[179-184]. In conclusion, using metformin before the development of MASLD does not confer any protective effects. Still, it may serve as an adjunct to lifestyle modification early in the disease course[185]. In HFpEF, the addition of metformin to ACEi and Beta blockers in patients with HFpEF was associated with decreased mortality[186].

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) agonists such as fibrates and thiazolidinediones are among the most extensively studied in MASLD. They selectively augment the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors engaged in glucose and lipid metabolism in various tissues to mitigate inflammation, fibrosis, and atherosclerosis[187,188]. These agonists are further classified into PPAR-alpha, PPAR beta/delta, and PPAR gamma. PPAR alpha inhibits hepatic steatosis by promoting fatty acid oxidation in the liver and NF-kB inhibition-mediated anti-inflammation, while sup

Current EASL-EASO-EASD and AASLD guidelines recommend the use of PPAR-gamma agonist Pioglitazone yet concerning side effects, such as weight gain and fluid retention, have been obstacles in its widespread use[127,209,210]. Consistent with these efforts, newer agents such as lobeglitazone, saroglitazar, elafibranor, and lanifibranor are currently under development.

SGLT-2i acts by attenuating glucose absorption in pre-renal tubules, preventing hyperglycemia. Furthermore, it inhibits glucose uptake in hepatocytes, which is robustly associated with antiproliferative activity across multiple hepatocellular lines[211]. Finally, in vitro studies have demonstrated that the pleiotropic nature of these agents enables modulation of glucose and cholesterol metabolism, suppression of inflammation, weight loss, and reversal of steatosis and fibrosis[212-214].

AASLD recommends using SGLT2i for NAFLD-associated cardiometabolic diseases[172]. Drugs such as dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and canagliflozin have been shown to decrease liver fat and are routinely used as antidiabetic agents[215]. SGLT2i plays a significant role in inducing peripheral insulin sensitivity, upregulating beta cell mass, and reducing oxidative stress[216-219]. SGLT2i provides more significant weight loss benefits and anti-hypertensive effects than metformin and dipeptidyle peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors[220]. Furthermore, glycemic control, weight loss, and anti-hypertensive benefits are additive when combined with Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), leading to decreased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications[221,222].

SGLT2i has also been reported to have beneficial effects on OSA, diabetes, blood pressure, arrhythmias, renal damage, and anemia in patients with HFpEF[223]. SGLT-2i impedes the pathophysiological impact of diabetes on HFpEF development and reduces mortality[224]. It exerts these effects by attenuating ER stress through upregulation of sirtuin-1, preventing myocardial injury by inhibiting Na-H exchange in the heart and kidneys, and reducing epicardial fat, thereby protecting against myocardial fibrosis and microcirculatory damage[224]. In addition to the benefits above, improved vascular physiology and pressure reduction confer protection against the risk of atrial arrhythmias by preventing atrial remodeling[225].

In conclusion, SGLT-2 use is tightly linked with decreased cardiovascular mortality, improved quality of life, and improved exercise capacity in patients with HFpEF[226-228]. The pleiotropic nature of SGLT-2i makes them attractive options in the potentiation of metabolic disease. It illustrates their inextricable link with a reduction in cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in patients with T2DM[229].

DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 RA, and, more recently, dual GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide RA tirzepa

Liraglutide and semaglutide have both been approved for the management of weight loss in obese patients, irrespective of diabetic status[231]. GLP-1 RA use has demonstrated better glycemic control, weight loss, and a favorable metabolic profile compared to insulin treatment, highlighting their role as effective anti-diabetic agents[232,233]. Tirzepatide was approved after the most recent EASL-EASO-EASD guidelines were published. It has demonstrated superiority to GLP-1 RAs in terms of glycemic control and weight loss and holds potential as a viable alternative in the near future[234]. Induction of insulin sensitivity is accredited to enhanced glucose-mediated insulin secretion at the pancreas, mitigation of postprandial hyperglycemia through retardation of gastric emptying, and lowered glycosylated hemoglobin with a net weight loss[235]. Peripherally, GLP-1 agonists cause early satiety through their action at the brainstem and hypothalamus, induce adipocyte apoptosis, decrease adipokine and cytokine production, and promote glucose uptake by adipocytes and skeletal muscles, further reducing IR[236].

In conjunction with the aforementioned metabolic benefits, the direct action of incretin mimetics at the liver mitigates MASLD by indirectly modulating response to energy and nutrients. In trials, GLP-1 RAs have been robustly linked with reduced visceral and liver fat, irrespective of diabetic status. Another analysis noted a more significant reduction in steatosis associated with GLP-1 RA compared with other anti-diabetic agents, including SGLT-2i and PPAR agonists[237-239].

The role of GLP-1 RA in reversing fibrosis is indirect and attributed to its anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective effects. At a cellular level, these agents inhibit de novo lipogenesis by inhibiting regulators of the carbohydrate element binding protein (ChREPB) transcription factor, stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, and activation of AMPK. Interestingly, this pathway also hampers cardiac hypertrophy in mouse models[240]. Downstream, this results in decreased TG synthesis, hepatic gluconeogenesis, and VLDL production while promoting insulin signaling and glycogen synthesis in the liver[241]. Therefore, in MASLD patients, GLP-1 RA reduces cardiovascular events and mortality comparable to SGLT-2i and superior to other anti-diabetic agents, including metformin[242]. At the cellular level, its cardio-protective effect corre

Statins act on the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase and lowering serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-C levels and triglycerides[247,248]. These agents facilitate LDL clearance through modulation of protein kinase-A and potentiation of ChREPB and carnitine palmitoyltransferase[1]. Furthermore, these agents counter steatosis through modulation of PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha, alteration of adiponectin signaling, and impeding peripheral lipolysis[249-254]. Finally, statins retard fibrosis through alteration of the sonic hedgehog pathway. In summary, statins favor fatty acid oxidation, interfere with de novo lipogenesis, and prevent the progression of MASLD[255]. Furthermore, statins directly impact lipid profile and endothelial dysfunction and exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects[256].

Statins have been shown to prevent myocardial hypertrophy, fibrosis, and LVH as they mitigate microvascular dysfunction, lower coronary atherosclerosis, and improve the lipid profile[248]. Their pleiotropic action highlights their importance in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Statins prevent intimal thickening, cell replication, and recruitment of leukocytes recruitment of immune cells by inhibiting LFA-1 and ICAM, resulting in significant downregulation of GTPase synthesis[257,258]. Their favorable effect on metabolic profile further contributes to atheroprotection, as NO is essential for vasodilation, platelet aggregation, vascular smooth muscle proliferation, and immune cell recruitment[259-261]. As a result, statins are established as agents that improve cardiovascular outcomes through primary and secondary prevention.

In MASLD, the benefit of RAAS inhibition is attributed to the modulation of cardiometabolic risk factors leading to improved metabolic profile and weight loss[262-264]. Furthermore, ACEi use in MASLD patients is correlated with reduced progression to cancer and cirrhosis[265]. In experimental models, ACE-I and ARB have inhibited cellular processes linked with AT-II that favor lipogenesis, adipocyte growth, adipokine release, and proinflammatory cytokine release and interfere with insulin receptor-PI3K signaling[264,266-271]. In addition, vasodilation improves pancreatic blood supply, enhances insulin secretion, improves glucose metabolism, and facilitates glucose delivery and uptake by peripheral insulin-sensitive tissue[272,273].

The anti-fibrotic effect of ACE-I and ARB is attributed to their modulation of AT-II and renin. Renin enhances the release of TGF-beta1, PAI-1, fibronectin, and collagen, while AT-II increases hepatic stellate cell activation, migration, and concentration. AT-II also converts hepatic stellate cells to myofibroblasts. Simultaneously, it upregulates tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase-1 release that secretes and incorporates collagen into the extracellular matrix. In addition, ACE-I and ARB inhibit ROS generation and decrease cytokine levels that further oppose fibrosis, lipogenesis, and IR[274-278].

MRAs, ARNi, and ARB are class 2b recommendations for treating HFpEF associated with decreased hospitalization, specifically in patients with EFs on the lower end of the spectrum.

These agents impede RAAS and mitigate arterial hypertension by altering vascular tone, enhancing sympathetic activity, and activating other downstream hormones[273,279,280].

Beta-blockers (BB) use has been traditionally limited in NAFLD due to its negative effect on glucose and lipid metabolism[281]. Traditionally, non-selective BB use has been associated with improved survival in HCC due to its role in attenuating vascular remodeling and portal hypertension and ultimately delaying decompensation[282]. On the other hand, BB use has been associated with lower exercise capacity in HFpEF. However, newer BB, such as nebivolol and carvedilol, have improved cardiometabolic risk factors, insulin sensitization, and metabolic profile[283,284]. This effect is attributed to their ability to peripherally mitigate afterload, lower glucose levels, and inhibit obesity-mediated hypertension[285].

Several novel treatments for MASLD are being developed and tested in Phase 2 or 3 clinical trials. These drugs may affect HFpEF by modifying shared risk factors that contribute to the development of both conditions. Lanifibranor, a pan-PPAR agonist, is undergoing Phase-3 trials[286]. Saroglitazar acts as an agonist on PPAR/α/γ receptors, and its efficacy in improving fibrosis is being evaluated in a 4-arm randomized trial[287]. Resmetirom is a thyroid hormone receptor β agonist that helps regulate lipid metabolism in the liver. It effectively reduced liver fat content in a Phase-2 trial and was recently approved in March 2024 for the management of NASH with F2 and F3 fibrosis[288]. VK-2809 is an alternative THR β agonist associated with lower hepatic fat deposition being studied in Phase-2 trials[289]. Semaglutide is undergoing Phase-3 trials to evaluate its ability to resolve MASLD and improve fibrosis. Aldafermin and Pegbelfermin are FGF 21 analogs that are being tested in Phase-2 trials, as FGF also play critical roles in metabolizing glucose, lipids, and bile acids. Pegbelfermin efficiently reduced hepatic fat and is now being tested in patients with Stage-3 fibrosis[290]. Galectins are proteins involved in inflammation and fibrosis. The Galectin-3 inhibitor Belapectin is being tested in adults with MASLD-associated cirrhosis and portal hypertension. It has reduced the hepatic venous pressure gradient in patients without varices and is thus being tested in Phase-3 trials[291].

Stem cell therapy is based on recent evidence that indicates a complex interplay between various cardiometabolic risk factors and their impact on genetics. Mesenchymal stem cells are unique in their ability to differentiate into distinct cell types and may serve to repair damaged tissue. These cells enhance tissue regeneration through various growth factors and amplify the ability of the body to generate stem cells[292]. Furthermore, as a testament to their pluripotency, MSCs alter their phenotype based on the inflammatory cytokine encountered and alter macrophages to aid in tissue repair[292-295]. MSC therapy improved LV ejection fraction in patients after myocardial infarction and has been shown to mount a favorable immune response in ischemic cardiomyopathy, emphasizing its potential as a breakthrough therapy in the future[296-298]. Nevertheless, clinical trial data have been varied, and these drugs have not yet been tested in HFpEF or MASLD populations. Figures 5 and 6 highlight the critical chains of interactions between HFpEF and MASLD, which serve as pharmacological targets, and the currently available drugs, which reduce the burden of MASLD and HFpEF. Table 1 highlights the most recent mechanistic evidence linking disease progression in MASLD and HFpEF.

| Ref. | Mechanistic link | Model |

| Nasiri-Ansari et al[212], 2021 | Empagliflozin attenuates MASLD progression in ApoE-/- mice by promoting hepatic autophagy, reducing ER stress, and inhibiting hepatocyte apoptosis | ApoE-/- mice |

| Li et al[214], 2021 | Dapagliflozin alleviates hepatic steatosis and protects against liver inflammation and fibrosis by reducing lipid accumulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses | Mouse (DIO/MASLD model) |

| Wang et al[54], 2021 | FGF1ΔHBS prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress via AMPK/Nur77 suppression | Diabetic mice |

| Schiattarella et al[67], 2019 | iNOS-driven nitrosative stress leads to coronary microvascular inflammation and rarefaction, driving concentric remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF | ZSF1 rat model |

| Hopf et al[182], 2018 | Insulin resistance impairs titin phosphorylation via reduced PKG/PKA signaling, increasing cardiomyocyte stiffness and promoting HFpEF in diabetes | Human cardiomyocytes |

| Slater et al[183], 2019 | Metformin improves diastolic function in an HFpEFlike mouse model by lowering titinbased passive stiffness and enhancing titin compliance via PKG-N2BA isoform shift | HFpEF mouse model |

| Zhao et al[110], 2019 | Digoxin inhibits PKM2 and thereby suppresses HIF-1α and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, attenuating steatohepatitis and associated inflammation | Mouse (MASH model) |

MASLD has emerged as the leading cause of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis worldwide in the last 3 decades. The exponential increase in global MASLD prevalence is closely related to the sharp rise in metabolic disease prevalence, including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia, in both developed and developing countries. In addition, the same period has seen increases in the incidence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Shared risk factors on the background of metabolic dysfunction have made a common ground for further exploring the link between MASLD and CVD, particularly HfpEF. The consistent pool of evidence supports the higher risk of CVD in MASLD, as well as a bidirectional relationship between MASLD and HfpEF. Furthermore, the extent of fibrosis in MASLD has been shown to correlate with HFpEF prognosis and progression.

| 1. | Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, Swain MG, Congly SE, Kaplan GG, Shaheen AA. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:851-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 1459] [Article Influence: 364.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lim GEH, Tang A, Ng CH, Chin YH, Lim WH, Tan DJH, Yong JN, Xiao J, Lee CW, Chan M, Chew NW, Xuan Tan EX, Siddiqui MS, Huang D, Noureddin M, Sanyal AJ, Muthiah MD. An Observational Data Meta-analysis on the Differences in Prevalence and Risk Factors Between MAFLD vs NAFLD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:619-629.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simon TG, Ebrahimi F, Roelstraete B, Hagström H, Sundström J, Ludvigsson JF. Incident cardiac arrhythmias associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a nationwide histology cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mantovani A, Csermely A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Corey KE, Simon TG, Byrne CD, Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:903-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77:1335-1347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 1995] [Article Influence: 665.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Wijarnpreecha K, Lou S, Panjawatanan P, Cheungpasitporn W, Pungpapong S, Lukens FJ, Ungprasert P. Association between diastolic cardiac dysfunction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:1166-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jung JY, Park SK, Ryoo JH, Oh CM, Kang JG, Lee JH, Choi JM. Effect of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on left ventricular diastolic function and geometry in the Korean general population. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:522-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chung GE, Lee JH, Lee H, Kim MK, Yim JY, Choi SY, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Kim D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis are associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Atherosclerosis. 2018;272:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Salah HM, Pandey A, Soloveva A, Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM, Moylan CA, Wegermann K, Rao VN, Hernandez AF, Tedford RJ, Parikh KS, Mentz RJ, McGarrah RW, Fudim M. Relationship of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6:918-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Erratum: Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis is Associated with Cardiac Remodeling and Dysfunction. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25:1639-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | VanWagner LB, Wilcox JE, Ning H, Lewis CE, Carr JJ, Rinella ME, Shah SJ, Lima JAC, Lloyd-Jones DM. Longitudinal Association of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Changes in Myocardial Structure and Function: The CARDIA Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shuster A, Patlas M, Pinthus JH, Mourtzakis M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: a critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Batta A, Hatwal J. Excess cardiovascular mortality in men with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A cause for concern! World J Cardiol. 2024;16:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Pacana T, Cazanave S, Verdianelli A, Patel V, Min HK, Mirshahi F, Quinlivan E, Sanyal AJ. Dysregulated Hepatic Methionine Metabolism Drives Homocysteine Elevation in Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oh A, Okazaki R, Sam F, Valero-Muñoz M. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Adipose Tissue: A Story of Two Tales. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qiu M, Li J, Hao S, Zheng H, Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhu X, Hu Y, Cai X, Huang Y. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with a worse prognosis in patients with heart failure: A pool analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1167608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fudim M, Zhong L, Patel KV, Khera R, Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM, McGarrah RW, Molinger J, Moylan CA, Rao VN, Wegermann K, Neeland IJ, Halm EA, Das SR, Pandey A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Risk of Heart Failure Among Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miller A, McNamara J, Hummel SL, Konerman MC, Tincopa MA. Prevalence and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wegermann K, Fudim M, Henao R, Howe CF, McGarrah R, Guy C, Abdelmalek MF, Diehl AM, Moylan CA. Serum Metabolites Are Associated With HFpEF in Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e029873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Minhas AMK, Bhopalwala HM, Dewaswala N, Salah HM, Khan MS, Shahid I, Biegus J, Lopes RD, Pandey A, Fudim M. Association of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With in-Hospital Outcomes in Primary Heart Failure Hospitalizations With Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48:101199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Takahashi T, Watanabe T, Shishido T, Watanabe K, Sugai T, Toshima T, Kinoshita D, Yokoyama M, Tamura H, Nishiyama S, Arimoto T, Takahashi H, Yamanaka T, Miyamoto T, Kubota I. The impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score on cardiac prognosis in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:733-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Itier R, Guillaume M, Ricci JE, Roubille F, Delarche N, Picard F, Galinier M, Roncalli J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: from pathophysiology to practical issues. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Petta S, Argano C, Colomba D, Cammà C, Di Marco V, Cabibi D, Tuttolomondo A, Marchesini G, Pinto A, Licata G, Craxì A. Epicardial fat, cardiac geometry and cardiac function in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: association with the severity of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoshihisa A, Sato Y, Yokokawa T, Sato T, Suzuki S, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Yamaki T, Kunii H, Nakazato K, Saitoh SI, Takeishi Y. Liver fibrosis score predicts mortality in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2018;5:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Abudureyimu M, Luo X, Wang X, Sowers JR, Wang W, Ge J, Ren J, Zhang Y. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in type 2 diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. J Mol Cell Biol. 2022;14:mjac028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fudim M, Sobotka PA, Dunlap ME. Extracardiac Abnormalities of Preload Reserve: Mechanisms Underlying Exercise Limitation in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction, Autonomic Dysfunction, and Liver Disease. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e007308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Austin P, Gerber L, Paik JM, Price JK, Escheik C, Younossi ZM. Aerobic capacity and exercise performance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019;59:1376-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Reddy P, Lent-Schochet D, Ramakrishnan N, McLaughlin M, Jialal I. Metabolic syndrome is an inflammatory disorder: A conspiracy between adipose tissue and phagocytes. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;496:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Francque SM, van der Graaff D, Kwanten WJ. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiological mechanisms and implications. J Hepatol. 2016;65:425-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mokotedi L, Michel FS, Mogane C, Gomes M, Woodiwiss AJ, Norton GR, Millen AME. Associations of inflammatory markers with impaired left ventricular diastolic and systolic function in collagen-induced arthritis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bruha R, Vitek L, Smid V. Osteopontin - A potential biomarker of advanced liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Coculescu BI, Manole G, Dincă GV, Coculescu EC, Berteanu C, Stocheci CM. Osteopontin - a biomarker of disease, but also of stage stratification of the functional myocardial contractile deficit by chronic ischaemic heart disease. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019;34:783-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stahl EP, Dhindsa DS, Lee SK, Sandesara PB, Chalasani NP, Sperling LS. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Heart: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:948-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | White PJ, Newgard CB. Branched-chain amino acids in disease. Science. 2019;363:582-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Perseghin G, Lattuada G, De Cobelli F, Esposito A, Belloni E, Ntali G, Ragogna F, Canu T, Scifo P, Del Maschio A, Luzi L. Increased mediastinal fat and impaired left ventricular energy metabolism in young men with newly found fatty liver. Hepatology. 2008;47:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lautamäki R, Borra R, Iozzo P, Komu M, Lehtimäki T, Salmi M, Jalkanen S, Airaksinen KE, Knuuti J, Parkkola R, Nuutila P. Liver steatosis coexists with myocardial insulin resistance and coronary dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E282-E290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nardelli S, Riggio O, Gioia S, Puzzono M, Pelle G, Ridola L. Spontaneous porto-systemic shunts in liver cirrhosis: Clinical and therapeutical aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:1726-1732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 38. | Koulava A, Sannani A, Levine A, Gupta CA, Khanal S, Frishman W, Bodin R, Wolf DC, Aronow WS, Lanier GM. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Orthotopic Liver Transplant Candidates With Portopulmonary Hypertension. Cardiol Rev. 2018;26:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fernández-Rodriguez CM, Prieto J, Zozaya JM, Quiroga J, Guitián R. Arteriovenous shunting, hemodynamic changes, and renal sodium retention in liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1139-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Oktay AA, Rich JD, Shah SJ. The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10:401-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bullard KM, Cowie CC, Lessem SE, Saydah SH, Menke A, Geiss LS, Orchard TJ, Rolka DB, Imperatore G. Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes in Adults by Diabetes Type - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:359-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Park JJ. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure in Diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2021;45:146-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ren J, Wu NN, Wang S, Sowers JR, Zhang Y. Obesity cardiomyopathy: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Physiol Rev. 2021;101:1745-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Wintergerst KA, Keller BB, Cai L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:585-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 45. | Patel N, Ju C, Macon C, Thadani U, Schulte PJ, Hernandez AF, Bhatt DL, Butler J, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Temporal Trends of Digoxin Use in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure: Analysis From the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:348-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Handoko ML, Falcao-Pires I, Musters RJ, Kupreishvili K, Ijsselmuiden AJ, Schalkwijk CG, Bronzwaer JG, Diamant M, Borbély A, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ, Laarman GJ, Niessen HW, Paulus WJ. Diastolic stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: importance of fibrosis, advanced glycation end products, and myocyte resting tension. Circulation. 2008;117:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Jou J, Choi SS, Diehl AM. Mechanisms of disease progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:370-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Boyer JK, Thanigaraj S, Schechtman KB, Pérez JE. Prevalence of ventricular diastolic dysfunction in asymptomatic, normotensive patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:870-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kashiwagi A, Araki S, Maegawa H. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors represent a paradigm shift in the prevention of heart failure in type 2 diabetes patients. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12:6-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ananthram MG, Gottlieb SS. Renal Dysfunction and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2021;17:357-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wold LE, Ceylan-Isik AF, Ren J. Oxidative stress and stress signaling: menace of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:908-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ayton SL, Gulsin GS, McCann GP, Moss AJ. Epicardial adipose tissue in obesity-related cardiac dysfunction. Heart. 2022;108:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Low Wang CC, Hess CN, Hiatt WR, Goldfine AB. Clinical Update: Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Mechanisms, Management, and Clinical Considerations. Circulation. 2016;133:2459-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 800] [Article Influence: 80.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Wang D, Yin Y, Wang S, Zhao T, Gong F, Zhao Y, Wang B, Huang Y, Cheng Z, Zhu G, Wang Z, Wang Y, Ren J, Liang G, Li X, Huang Z. FGF1(ΔHBS) prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress via AMPK/Nur77 suppression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Pyun JH, Kim HJ, Jeong MH, Ahn BY, Vuong TA, Lee DI, Choi S, Koo SH, Cho H, Kang JS. Cardiac specific PRMT1 ablation causes heart failure through CaMKII dysregulation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Clemenza F, Citarrella R, Patti A, Rizzo M. Obesity and HFpEF. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Pandey A, Patel KV, Vaduganathan M, Sarma S, Haykowsky MJ, Berry JD, Lavie CJ. Physical Activity, Fitness, and Obesity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Westcott F, Dearlove DJ, Hodson L. Hepatic fatty acid and glucose handling in metabolic disease: Potential impact on cardiovascular disease risk. Atherosclerosis. 2024;394:117237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Wohlfahrt P, Redfield MM, Lopez-Jimenez F, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Rodeheffer RJ, Borlaug BA. Impact of general and central adiposity on ventricular-arterial aging in women and men. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:489-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Russo C, Sera F, Jin Z, Palmieri V, Homma S, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, Di Tullio MR. Abdominal adiposity, general obesity, and subclinical systolic dysfunction in the elderly: A population-based cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:537-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Koepp KE, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Olson TP, Borlaug BA. Hemodynamic and Functional Impact of Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:657-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Borlaug BA, Reddy YNV. The Role of the Pericardium in Heart Failure: Implications for Pathophysiology and Treatment. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:574-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Sorimachi H, Jarolim P, Borlaug BA. Uncoupling between intravascular and distending pressures leads to underestimation of circulatory congestion in obesity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:353-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kitzman DW, Upadhya B, Vasu S. What the dead can teach the living: systemic nature of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015;131:522-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Ford DA, Hsu FF, Garcia R, Herrero P, Saffitz JE, Schaffer JE. A novel mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:813-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 585] [Cited by in RCA: 611] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism. 2019;92:82-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 885] [Article Influence: 126.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, French KM, Villalobos E, Kim SY, Luo X, Jiang N, May HI, Wang ZV, Hill TM, Mammen PPA, Huang J, Lee DI, Hahn VS, Sharma K, Kass DA, Lavandero S, Gillette TG, Hill JA. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. 2019;568:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 688] [Article Influence: 98.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Lauridsen BK, Stender S, Kristensen TS, Kofoed KF, Køber L, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjærg-Hansen A. Liver fat content, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and ischaemic heart disease: Mendelian randomization and meta-analysis of 279 013 individuals. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:385-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Gorter TM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Hummel YM, Lam CSP, Berger RMF, van Melle JP, Hoendermis ES. Right ventricular-vascular coupling in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pre- vs. post-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:425-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Polyzos SA, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in health and disease: facts and expectations at its twentieth anniversary. Metabolism. 2015;64:5-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Mendez-Sanchez N, Cruz-Ramon VC, Ramirez-Perez OL, Hwang JP, Barranco-Fragoso B, Cordova-Gallardo J. New Aspects of Lipotoxicity in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 72. | Nati M, Haddad D, Birkenfeld AL, Koch CA, Chavakis T, Chatzigeorgiou A. The role of immune cells in metabolism-related liver inflammation and development of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17:29-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Papadimitriou K, Mousiolis AC, Mintziori G, Tarenidou C, Polyzos SA, Goulis DG. Hypogonadism and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Endocrine. 2024;86:28-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Wells RG, Schwabe RF. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in the liver. Semin Liver Dis. 2015;35:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Anastasilakis AD, Triantafyllou GΑ, Mantzoros CS. Activin A and follistatin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1550-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Polyzos SA, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Zavos C, Kountouras J. Serum total adiponectin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2011;60:313-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 77. | Slivnick J, Lampert BC. Hypertension and Heart Failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2019;15:531-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |