IRON AND LIFE

Iron is a very important metal for all cells; iron deficiency results in cell death, but iron overload can be similarly detrimental. Adult humans have about 3 to 5 g of iron in the body, the vast majority of which is bound to haemoglobin[1]. The major iron storage in the body occurs in the liver, or more specifically, the hepatocytes, where most iron is bound to ferritin[2]. As iron is such a double-edged sword, its metabolism has to be tightly regulated and for a long time, both, a store regulator and a erythroid regulator have been hypothesised to regulate systemic iron needs[3]. It was also shown early on that both, iron deficiency and increased erythropoiesis were able to up-regulate iron absorption[4,5].

HEPCIDIN AS THE IRON STORE REGULATOR

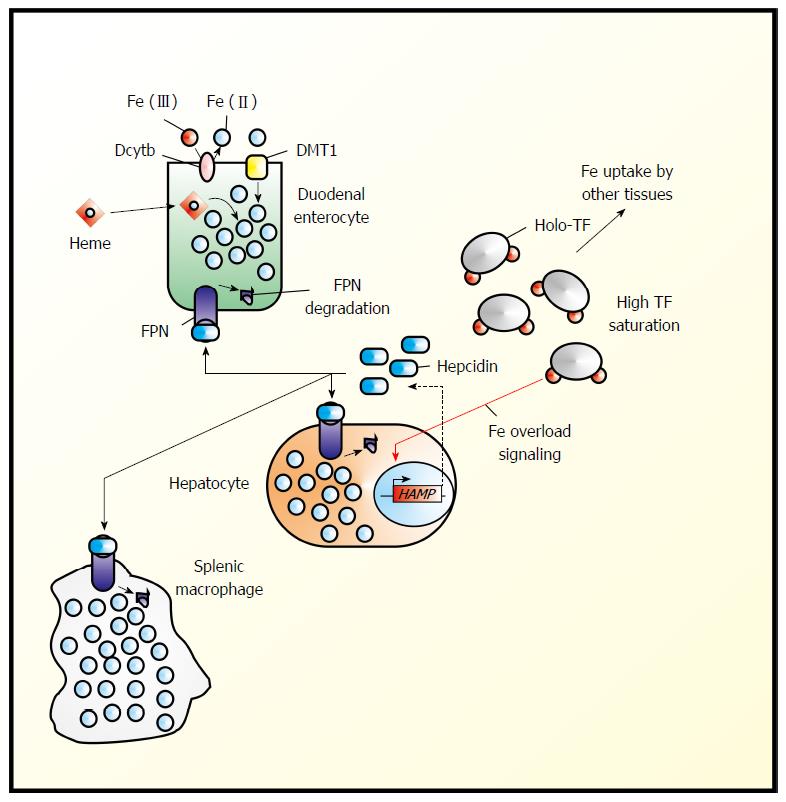

In 2000/2001, a small (25-amino-acid) hepatic antimicrobial peptide, LEAP-1 or hepcidin, was first described[6,7]. It was soon to be connected to iron metabolism and now is widely accepted to be the “store regulator”[5]. Murine hepcidin was found to be over-expressed during iron overload[8]. It is synthesized in response to high iron load and secreted by the liver into the blood stream, where the majority may bind unspecifically to albumin, while a small fraction (the active fraction?) will bind specifically to β2-macroglobulin, from which it can be delivered to ferroportin[9]. Once bound to ferroportin, the only known mammalian cellular iron exporter, it will trigger proteosomal ferroportin degradation and thereby lower iron release into the circulation (Figure 1)[1].

Figure 1 Hepcidin in the regulation of systemic iron homeostasis.

Systemic iron (Fe) homeostasis is primarily regulated by the hepcidin-ferroportin (FPN1) axis. Duodenal enterocytes import dietary Fe from several sources including heme Fe and non-heme Fe, which typically must be reduced at the level of the apical membrane by chemical reductants such as ascorbate[26,27] or by plasma membrane oxidoreductases (e.g., Dcytb), The reduced Fe then enters a common intracellular pool of Fe. “Sensing” the level of transferrin (TF) saturation and levels of Fe stores under conditions of Fe overload, hepatocytes up-regulate the expression of hepcidin, which is then released into the plasma where it can then bind to ferroportin (FPN1), thereby triggering FPN1 internalization and proteosomal degradation[1].

PROPOSED ERYTHROID REGULATORS OF IRON

The nature of the erythroid regulator on the other hand remained elusive. In order to be considered the erythroid regulator, the molecule should be independent of the total body iron stores, but up-regulated in anaemia; it should be up-regulated by erythropoietin and it should trigger the down-regulation of hepcidin. It also should be down-regulated after blood transfusion. Two candidates have been earlier identified, Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15) and Twisted Gastrulation (TWSG1)[10,11]. The former was identified as being up-regulated in thalassaemic serum by a transcriptional profiling approach during erythropoiesis and as being able to in vitro suppress hepcidin expression[10]. By transcriptome analyses of erythropoiesis, TWSG1 was identified as being up-regulated in early stages and again being able to (indirectly) suppress hepcidin expression[11]. For both these factors, however, evidence that they would constitute the erythroid regulator remained weak. Such, GDF15 levels are not correlated to hepcidin levels[12]. Even soluble transferrin receptor 1 was proposed to play the role of the erythroid regulator as it increases in iron deficiency and during increased erythropoiesis[13,14], however, this proposal also had to be dismissed, as it has no effect on iron absorption or hepcidin expression[14].

ERYTHROFERRONE - THE ERYTHROID REGULATOR?

Earlier this year erythroferrone, 340-amino acid soluble protein, was suggested for this role[15]. In response to erythropoietin, erythroblasts produce erythroferrone, which in turn suppresses hepcidin expression, resulting in increased release of iron from cellular iron stores[15]. Knockout mice for erythroferrone fail to rapidly suppress hepcidin expression in response to haemorrhage[15]. They also show a haemoglobin deficit, indicative of an impediment of erythropoiesis[15]. Erythroferrone expression in spleen and bone marrow increases during anaemia of inflammation and this contributes to iron mobilisation and recovery from anaemia[16].

MYONECTIN - A MYOKINE

These data provide strong evidence for erythroferrone finally being the (or at least an) erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. However, erythroferrone had earlier been described as “myonectin” or “C1q tumor necrosis factor α-related protein isoform 15” (CTRP15)[17]. [Unfortunately the same name “myonectin” was used in the same year for the related, but not identical “C1q tumor necrosis factor α-related protein isoform 5 (C1QTNF5)”[18] by Lim et al[19] for a myokine, the level of which is increased in insulin-resistant rats and mice and in myocytes depleted of mitochondrial DNA. This 243-amino acid soluble protein induces the phosphorylation on AMP-dependent protein kinase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase[20]]. CTRP15/myokine’s circulating level was described to be tightly regulated by the metabolic state (suppressed during fasting and up-regulated after re-feeding) and predominantly expressed in skeletal muscle[17].

A MYOKINE AS ERYTHROID REGULATOR OF IRON?

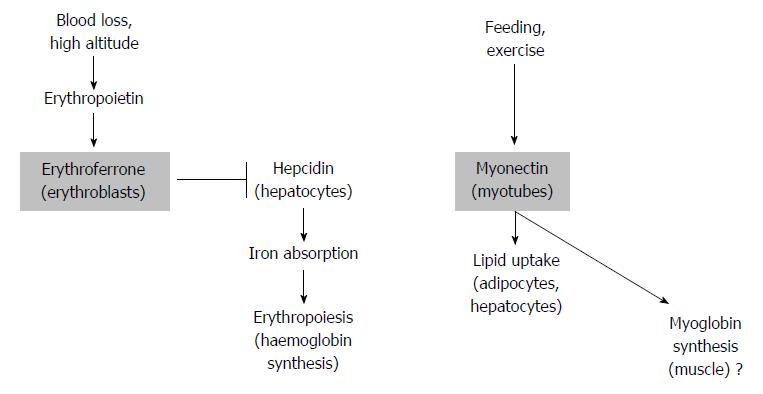

These authors did not include bone marrow or spleen in their expression analysis (the two tissues where erythropoietin significantly stimulated erythroferrone expression[15]) and neither analysed a knockout mouse of myonectin for a muscle phenotype (which was not reported for the erythroferrone knockout mouse[15]). Thus, it appears at first glance difficult to reconcile the two proposed functions of erythroferrone/myokine as those of a factor released into the circulation. Exercise, unless performed at high altitude, is not usually considered to stimulate erythropoiesis[21], neither is feeding. Thus, how can the apparent conundrum be solved that a myokine, that produced during exercise and feeding, enhancing fatty acid uptake by myocytes and hepatocytes[17] should be a master regulator of iron metabolism in erythropoiesis[15]? There appears to be discussion on whether continuous exercise (on sea level) can raise the erythropoietin levels and therefore erythropoiesis[22], thus there may be a way of reconciling the two functions of erythroferrone now described in the literature. Furthermore, a peptide stimulating haemoglobin formation in erythropoiesis may also have a role in myosin formation in the muscle (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Two potential actions of erythroferrone.

After blood loss, stress erythropoiesis is triggered by erythropoietin. This results in erythroferrone release from erythroblasts and in turn down-regulation of hepcidin. As a result, iron absorption and hemoglobin synthesis and erythropoiesis are increased (left). In response to feeding and exercise, myonectin (erythroferrone) produced by myotubes triggers fatty acid uptake by adipocytes and hepatocytes (right). Considering the function of erythroferrone in erythropoiesis, regulation of myoglobin is suggested to be a likely consequence of myonectin release (far right).

REGULATION OF ERYTHROFERRONE BY TRANSFERRIN RECEPTOR 2

While preparing this short editorial, several papers were published that provided evidence for a role of transferrin receptor 2 in the regulation of erythropoiesis. Wallace et al[23] reported that mice lacking matriptase-2 and transferrin receptor 2 are characterised by severe anaemia. These mice have a significantly increased erythroferrone expression when compared to their wild type litter mates during stress erythropoiesis. Similar results were presented by Nai et al[24] showing that mice lacking both matriptase-2 and transferrin receptor 2 have increased erythrocyte counts when compared to littermates only lacking matriptase-2. When analysing mice, lacking transferrin receptor 2 in the bone marrow only, Nai et al[25] reported that these mice exhibit increased numbers of nucleated erythroid cells in the bone marrow and increased erythroferrone levels in the spleen and in erythroid precursors.

CONCLUSION

C1q tumour necrosis factor α-related protein isoform 15, originally called myonectin and now referred to as erythroferrone, appears to play two different regulatory roles; that of a myokine and that of an erythroid regulator of iron. On the whole, evidence for its function as erythroid regulator of iron appears to be stronger than that of its function as myonectin. Transferrin receptor 2 also plays a regulatory role in erythropoiesis, down-regulating erythroferrone and thereby erythropoiesis. Transferrin receptor 2 may be involved in the iron sensing that results in the regulation of red blood cell formation.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Cairo G, Carter WG, Fujiwara N, Kan L S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH