Published online Mar 27, 2017. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i3.73

Peer-review started: July 17, 2016

First decision: September 2, 2016

Revised: October 28, 2016

Accepted: December 1, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: March 27, 2017

Processing time: 251 Days and 12.2 Hours

To characterize incidence and risk factors for delayed gastric emptying (DGE) following pancreaticoduodenectomy and examine its implications on healthcare utilization.

A prospectively-maintained database was reviewed. DGE was classified using International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery criteria. Patients who developed DGE and those who did not were compared.

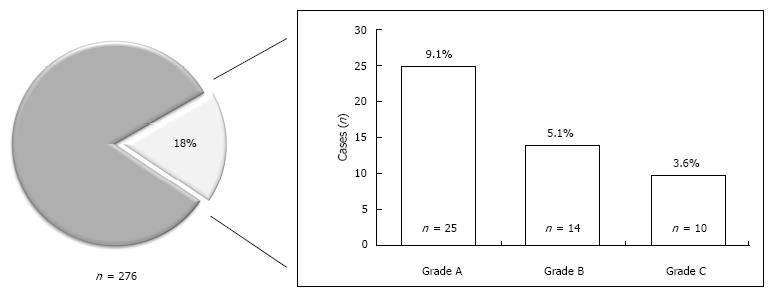

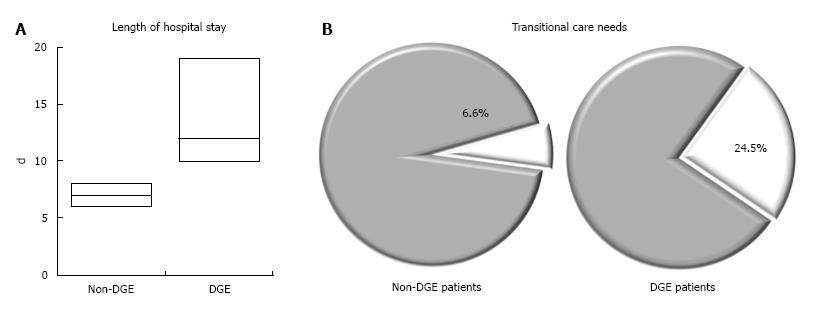

Two hundred and seventy-six patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) (> 80% pylorus-preserving, antecolic-reconstruction). DGE developed in 49 patients (17.8%): 5.1% grade B, 3.6% grade C. Demographic, clinical, and operative variables were similar between patients with DGE and those without. DGE patients were more likely to present multiple complications (32.6% vs 4.4%, ≥ 3 complications, P < 0.001), including postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) (42.9% vs 18.9%, P = 0.001) and intra-abdominal abscess (IAA) (16.3% vs 4.0%, P = 0.012). Patients with DGE had longer hospital stay (median, 12 d vs 7 d, P < 0.001) and were more likely to require transitional care upon discharge (24.5% vs 6.6%, P < 0.001). On multivariate analysis, predictors for DGE included POPF [OR = 3.39 (1.35-8.52), P = 0.009] and IAA [OR = 1.51 (1.03-2.22), P = 0.035].

Although DGE occurred in < 20% of patients after PD, it was associated with increased healthcare utilization. Patients with POPF and IAA were at risk for DGE. Anticipating DGE can help individualize care and allocate resources to high-risk patients.

Core tip: Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) frequently occurs following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Review of our institutional database revealed a DGE rate of less than 20% among patients who underwent PD. DGE was associated with increased healthcare utilization in terms of rates of various postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and need for transitional care upon discharge. Patients with post-operative pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess formation were at risk for DGE. Anticipating DGE can help individualize care and allocate resources to high-risk patients.

- Citation: Mohammed S, Van Buren II G, McElhany A, Silberfein EJ, Fisher WE. Delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: Incidence, risk factors, and healthcare utilization. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 9(3): 73-81

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v9/i3/73.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v9.i3.73

Advances in surgery and critical care have decreased postoperative mortality following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) to less than 5% in high-volume centers, and, in addition, the management of post-operative morbidity has also improved[1-4]. However, delayed gastric emptying (DGE) remains one of the most frequent complications following PD, affecting 15%-30% of patients post-operatively[5-8]. DGE has been associated with increased hospital stay, higher readmission rates, and impaired quality of life[9,10]. Previous studies have suggested various factors that may influence DGE development, including technical approaches to PD (such as classic vs pylorus-preserving resection, antecolic vs retrocolic reconstruction) and presence of other intra-abdominal complications (such as pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess formation)[11-17].

The aims of this study were to examine a patient database and: (1) determine the incidence of DGE; (2) assess potentially associated risk factors for DGE; and (3) examine the impact of DGE on health care utilization. We hypothesized that the rate of DGE would be comparable to those reported in the literature; that other complications, such as postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) formation, may increase likelihood of DGE occurrence; and that DGE would be associated with increased use of health care resources.

A prospectively-maintained database was queried to identify 276 consecutive patients who underwent PD at a single institution between 2005 and 2013. Data elements were extracted from this prospectively maintained database and charts were retrospectively reviewed to corroborate variables of interest. The 276 patients were classified into two groups: The group of patients who experienced postoperative DGE and the group of patients who did not.

Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes data were obtained from the medical charts and entered into a prospectively maintained database. Specific demographic data included age at time of diagnosis, gender, and race/ethnicity. The presence of co-morbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, chronic pancreatitis, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and obesity were recorded, as were clinical characteristics such as presenting symptoms and specific laboratory values. The anesthesia reports were reviewed to record the American Society of Anesthesiologists classification score, operative time (defined as the time from incision to application of the final wound dressing), the estimated intraoperative blood loss, and intraoperative transfusion data. The operative reports were reviewed to record details of the procedure and intraoperative characteristics of the pancreas, such as texture and pancreatic duct size.

The primary outcome of interest was development of postoperative DGE, which was defined and graded using the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) criteria[18]. With this definition, the severity of DGE was classified into grades based on the number of days nasogastric drainage was required and the number of days until solid oral intake was tolerated (Table 1). Grades B and C DGE were considered clinically significant.

| DGE grade | NGT required | Unable to tolerate solids orally by | Vomiting/distention | Use of prokinetics |

| A | 4-7 d or reinsertion > POD 3 | POD 7 | ± | ± |

| B | 8-14 d or reinsertion > POD 7 | POD 14 | + | + |

| C | 14 d or reinsertion > POD 14 | POD 21 | + | + |

Secondary outcomes of interest included rates of graded 90-d complications, length of hospital stay, reoperations and readmission rates, and need for transitional care upon hospital discharge. Operative mortality was defined as any death within 90 d of surgery. All complications were recorded using specific and standardized definitions. Complications were graded in severity using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events CTCAE (v4.03) (grade 1-5) unless otherwise specified[19]. Pancreatic fistula was graded using the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition[20].

A descriptive analysis of the overall study cohort was performed. A univariate comparison of demographic, clinical, operative, and pathologic factors was performed between patients with and without DGE using Student t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. In addition to the ISGPF definition for fistula, we also applied the fistula risk score (FRS) developed by Callery et al[21] to determine any potential association between the score and clinically significant DGE. The FRS is a ten-point scale that takes into consideration the weighted influence of four variables (soft pancreatic parenchyma, increased intraoperative blood loss, small duct size, and high-risk pathology) and may correlate with clinically relevant POPF development[21]. Multivariate logistic regression was then used to determine independent predictors of DGE in this cohort. Finally, data of the 49 DGE patients were further analyzed to determine duration of DGE, need for nutritional support, length of hospital stay, and discharge to transitional care facilities.

All results were reported with the appropriate summary statistic, measure of dispersion/variance, and measure of statistical significance. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package or the Social Sciences, version 21 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Of the 276 patients that underwent PD during the study period, 49 (17.8%) developed DGE. Of the 49 patients with DGE, 25 (9.1%) developed grade A, 14 (5.1%) developed grade B, and 10 (3.6%) developed grade C DGE (Figure 1). Characteristics of the overall study population and patients with and without DGE are shown in Table 2.

| Overall (n = 276) | No DGE group (n = 227) | DGE Group (n = 49) | P values | |

| Age | 63.2 ± 11.92 | 62.9 ± 11.95 | 64.6 ± 11.77 | 0.348 |

| Gender | 0.339 | |||

| Male | 135 (48.9%) | 108 (47.6%) | 27 (55.1%) | |

| Female | 141 (51.1%) | 119 (52.4%) | 22 (44.9%) | |

| Co-morbid conditions | ||||

| HTN | 147 (53.3%) | 119 (52.4%) | 28 (57.1%) | 0.568 |

| COPD | 13 (4.7%) | 11 (4.8%) | 2 (4.1%) | 1 |

| DM | 67 (24.3%) | 58 (25.6%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.288 |

| CRI | 8 (2.9%) | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.635 |

| History of pancreatitis | 42 (15.2%) | 36 (15.9%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.557 |

| History of ETOH use | 122 (44.2%) | 102 (44.9%) | 20 (40.8%) | 0.702 |

| History of tobacco use | 57 (20.7%) | 49 (21.6%) | 8 (16.3%) | 0.390 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 26.7 ± 7.1 | 27.1 ± 7.28 | 25.6 ± 6.91 | 0.226 |

| Presenting symptoms | ||||

| Weight loss | 140 (50.7%) | 115 (50.7%) | 25 (51.0%) | 0.921 |

| Anorexia | 29 (10.5%) | 24 (10.6%) | 5 (10.2%) | 0.873 |

| Early satiety | 17 (6.2%) | 16 (7.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.323 |

| Nausea | 83 (30.1%) | 74 (32.6%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.058 |

| Vomiting | 43 (15.6%) | 40 (17.6%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.048 |

| Jaundice | 122 (44.2%) | 103 (45.4%) | 19 (38.8%) | 0.419 |

| Preop albumin | 4.0 ± 0.60 | 4.0 ± 0.59 | 3.8 ± 0.62 | 0.038 |

| Preop total bilirubin | 2.5 ± 4.29 | 2.7 ± 4.49 | 1.8 ± 3.11 | 0.139 |

| Preop hemoglobin | 12.8 ± 1.85 | 12.8 ± 1.87 | 12.7 ± 1.76 | 0.734 |

| Preop Cr > 1.2 | 40 (14.5%) | 31 (13.7%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.378 |

Patients with DGE had demographic features and clinical characteristics similar to those of patients without DGE. The majority of the patients (n = 221, 80.1%) underwent pylorus-preserving PD with antecolic hand-sewn enteric anastomosis (Table 3). None of the patients received a gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube and all nasogastric drainage tubes were removed in the operating room upon completion of the operation. Patients who developed DGE underwent procedures of comparable duration and had no significantly higher intraoperative blood losses. There was also no difference in the use of anastomotic pancreatic duct stents, the texture of the pancreas, or the distribution of pathological diagnoses in either group. The frequency and severity of complications were increased among patients who experienced DGE. Forty of the 49 patients (81.6%) with DGE presented at least 1 other complication, whereas in the group of patients without DGE, 70% of patients presented no complications at all. Of the 49 patients with DGE, 37 (75.5%) had at least 1 complication greater than grade 2 severity in comparison to only 20.7% of patients in the group without DGE. Post-operatively, pancreatic fistula developed in 64 (23.2%) patients. Patients with DGE were more likely to experience clinically significant POPF than those without DGE (22.4% vs 6.2% grade B-C POPF, P < 0.001). Patients with DGE were also more likely to have intra-abdominal abscess (16.3% vs 4.0%, P = 0.012) (Table 4).

| Overall (n = 276) | No DGE group (n = 227) | DGE group (n = 49) | P values | |

| ASA class | 0.398 | |||

| 1 | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 78 (28.3%) | 59 (26.0%) | 19 (38.8%) | |

| 3 | 172 (62.3%) | 144 (63.4%) | 28 (57.1%) | |

| 4 | 16 (5.8%) | 14 (6.2%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Operative time | 452.1 ± 100.6 | 450.0 ± 100.87 | 461.6 ± 99.7 | 0.467 |

| Procedure performed | 0.169 | |||

| Classic | 55 (19.9%) | 49 (21.6%) | 6 (12.2%) | |

| Pylorus-preserving | 221 (80.1%) | 178 (78.4%) | 43 (87.8%) | |

| EBL | 515.7 ± 571.4 | 509.3 ± 533.59 | 544.0 ± 722.99 | 0.702 |

| Transfusions | 49 (17.8%) | 37 (16.3%) | 12 (24.5%) | 0.178 |

| Pancreas texture | 0.264 | |||

| Soft | 144 (52.2%) | 115 (50.7%) | 29 (59.2%) | |

| Firm/hard | 121 (64.8%) | 103 (45.4%) | 18 (36.7%) | |

| PD size | 4.2 ± 2.29 | 4.3 ± 2.21 | 4.1 ± 2.65 | 0.612 |

| PD anastomotic stent | 117 (42.4%) | 99 (43.6%) | 18 (36.7%) | 0.377 |

| Vein resection | 41 (14.9%) | 34 (15.0%) | 7 (14.3%) | 0.902 |

| Pathological diagnosis | ||||

| PDAC | 118 (42.8%) | 103 (45.4%) | 15 (30.6%) | 0.058 |

| Neuroendocrine | 12 (4.3%) | 11 (4.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.383 |

| Ampullary | 38 (13.8%) | 30 (13.2%) | 8 (16.3%) | 0.567 |

| Cystic | 41 (14.9%) | 32 (14.1%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.446 |

| Pancreatitis | 33 (12.0%) | 28 (12.3%) | 5 (10.2%) | 0.677 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 7 (2.5%) | 5 (2.2%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.807 |

| Other | 27 (9.8%) | 18 (7.9%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.026 |

| Fistula risk score | ||||

| Negative (0 points) | 34 (12.4%) | 28 (12.4%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.861 |

| Low (1-2 points) | 62 (22.6%) | 58 (25.7%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.008 |

| Moderate (3-6 points) | 138 (50.2%) | 106 (46.9%) | 32 (65.3%) | 0.020 |

| High (7-10 points) | 30 (10.9%) | 24 (10.6%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.741 |

| Overall (n = 276) | No DGE group (n = 227) | DGE group (n = 49) | P values | |

| Frequency of other complications (any grade) | ||||

| Patients with 0 complications | 157 (56.9%) | 157 (69.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Patients with 1 complication | 51 (18.5%) | 42 (18.5%) | 9 (18.4%) | 0.982 |

| Patients with 2 complications | 42 (15.2%) | 18 (7.9%) | 24 (49.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Patients with 3 complications | 11 (4.0%) | 5 (2.2%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.005 |

| Patients with 4 complications | 8 (2.9%) | 5 (2.2%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.153 |

| Patients with ≥ 5 complications | 7 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (14.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Severity of complications | ||||

| Patients with any complication ≥ Grade 3 | 60 (21.7%) | 38 (16.7%) | 22 (44.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Patients with any complication ≥ Grade 2 | 84 (30.4%) | 47 (20.7%) | 37 (75.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Patients with any complication ≥ Grade 1 | 119 (43.1%) | 70 (30.8%) | 49 (100.0%) | < 0.001 |

| 90-d mortality | 6 (2.2%) | 4 (1.8%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.289 |

| Re-operations | 12 (4.3%) | 10 (4.4%) | 2 (4.1%) | 1 |

| Readmissions | 40 (14.5%) | 33 (14.5%) | 7 (14.3%) | 1 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 64 (23.2%) | 43 (18.9%) | 21 (42.9%) | 0.001 |

| Grade A | 39 (14.1%) | 29 (12.8%) | 10 (20.4%) | |

| Grade B | 19 (6.9%) | 11 (4.8%) | 8 (16.3%) | |

| Grade C | 6 (2.2%) | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (6.1%) | |

| Bile leak | 4 (1.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.019 |

| Wound infection | 20 (7.2%) | 12 (5.3%) | 8 (16.3%) | 0.013 |

| Wound dehiscence | 3 (1.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.082 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 17 (6.2%) | 9 (4.0%) | 8 (16.3%) | 0.012 |

| Line infection | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.033 |

| Clostridium difficile | 4 (1.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.019 |

| Benign fluid collection | 5 (1.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (6.1%) | 0.041 |

| Pneumonia | 9 (3.3%) | 5 (2.2%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.056 |

| Urinary tract infection | 10 (3.6%) | 5 (2.2%) | 5 (10.2%) | 0.018 |

| Respiratory failure | 9 (3.3%) | 3 (1.3%) | 6 (12.2%) | 0.001 |

| Encephalopathy | 5 (1.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.004 |

| Arrhythmia | 16 (5.8%) | 6 (2.6%) | 10 (20.4%) | < 0.001 |

| MI | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.545 |

| DVT | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| PE | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| Hemorrhage | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.545 |

| Renal failure | 5 (1.8%) | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.216 |

| Hepatic failure | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.182 |

| SMV/PV Thrombosis | 8 (2.9%) | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (4.1%) | 0.635 |

DGE lasted 8.7 d on average. However, many of the patients in the cohort had grade 1 DGE and, when excluded, the average duration of clinically significant grade B-C DGE was 14.5 d. A nasogastric tube was inserted in 14 of 24 patients (58.3%) with grade B-C DGE and managed with TPN in 69.8% of patients. Patients with DGE had a longer hospital stay (median, 12 d vs 7 d, P < 0.001) and were more likely to be discharged to transitional care facilities (24.5% vs 6.6%, P < 0.001) (Figure 2). They were equally likely to require reoperations or readmissions. Analysis of the FRS showed that 77.5% of patients with DGE had moderate or high scores (vs 57.5% of patients without DGE who had moderate or high scores). On multivariate analysis, patients with clinically significant post-operative pancreatic fistula formation and intra-abdominal abscess formation had a higher likelihood of having delayed gastric emptying (Table 5).

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 3.39 (1.35-8.52) | 0.009 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1.51 (1.03-2.22) | 0.035 |

| PDAC diagnosis | 1.01 (0.524-1.94) | 0.982 |

| Moderate/high FRS | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | 0.463 |

Delayed gastric emptying is one of the most common complications following PD, but it remains difficult to predict. Previous studies have suggested various factors associated with DGE development, such as technical approaches to pancreatectomy (classic vs pylorus-preserving resection or antecolic vs retrocolic reconstruction), and presence of other intra-abdominal complications such as pancreatic fistula or intraabdominal abscess formation[11-17]. In this series, we found a DGE rate of less than 20%; an association of DGE with a higher rate of post-operative complications, particularly post-operative pancreatic fistula formation; and significantly increased healthcare utilization, including longer length of hospital stay and greater need for transitional care upon discharge.

Most of our patients (n = 221, 80.1%) underwent pylorus-preserving PD without intraoperative placement of nasojejunal, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy tubes. All nasogastric tubes were removed in the operating room upon completion of the operation. Reinsertion of a nasogastric tube for gastric decompression, or inability to tolerate oral intake, or abdominal distention, emesis, or need for prokinetic agents thus constituted DGE based on ISGPS criteria (Table 1). Although our DGE rate was relatively low and consistent with the rates of other reported series, it was associated with other complications and lengthier hospital stay, and this raised the question of whether specific interventions, such as prophylactic placement of enteric tubes, may be worthwhile to mitigate potential consequences of DGE.

Mack et al[22] conducted a randomized study between 1999 and 2002 to assess the feasibility and safety of prophylactically placing double-lumen gastrojejunostomy tubes in patients undergoing PD. They found that insertion of a gastrojejunostomy tube was safe and decreased the incidence of DGE, length of hospital stay, and hospital costs[22]. They viewed the insertion of the gastrojejunostomy tube as an adjunctive measure for providing gastric decompression without the need for a nasogastric tube or its associated risk for respiratory discomforts, and also as a means of providing enteral nutrition, should it be needed. No larger trials have been conducted to confirm Mack et al’s[22] findings or to determine the effect of similar interventions on long-term quality of life, nutritional outcomes, or receipt of oncologic care, such as time to initiation of adjuvant therapy. Widespread adoption of this approach in the perioperative setting would, however, expose the majority of patients to tubes they may not need postoperatively, as well as to associated complications, such as tube dislodgments, leaks, infections, aspiration, and peritonitis[23].

In our study, a nasogastric tube was inserted postoperatively for gastric decompression in 14 of 24 patients (58.3%) with grade B or C DGE. We did not observe any complications with placement of a nasogastric tube in the early postoperative period. If grade B or C DGE persisted, patients were either supported with TPN and/or a nasojejunal feeding tube for enteral feeding was placed by an interventional radiologist. We did not use endoscopically placed gastrostomy or combined gastrostomy-jejunal tubes. Although we did not perform any cost estimate analysis of parenteral vs enteral feeding in this cohort, it is well established that enteral nutrition is less costly than TPN[24,25]. Data from Mack et al[22], as well as cost-analysis modeling[26], demonstrated that costs for patients treated with a gastrojejunostomy tube were less than those for patients treated without a gastrojejunostomy, even though 100% of patients in the gastrojejunostomy group received nutritional supplementation compared with only 20% to 40% of the patients in the group treated by more standard methods[22,26].

In an era focused on increasing patient throughput and standardizing postoperative care plans, identifying patients who may deviate from the expected postoperative course and implementing strategies to curtail downstream effects is important. Placing enteral tubes in all patients undergoing PD would certainly result in significant over-treatment and risk complications associated with the tube. However, placement in patients at higher risk for developing DGE could potentially facilitate an earlier discharge, improve patient comfort, and decrease health care costs.

Our multivariate analysis showed that patients with pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess formation had a significantly higher likelihood of developing DGE. This correlation is consistent with those found in other published series[27,28]. In a large multi-institutional study of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pancreatectomy Demonstration Project, only pancreatic fistula, postoperative sepsis, and reoperation were independently associated with DGE in 711 patients undergoing PD or total pancreatectomy[27].

Although the majority of patients with DGE in this study also had other postoperative complications, we did identify 9 patients with isolated DGE. These patients were no different than patients without DGE with regards to clinical features or operative factors. Five of these 9 cases of DGE were clinically insignificant and lasted between 4 to 6 d. Although our DGE rate in this series is around 20%, which is consistent with those reported in the literature, this rate captures patients with even clinically-insignificant episodes of DGE as well as those patients who required insertion of nasogastric tube for reasons that may not have been related to DGE, such as prolonged intubation secondary to pneumonia. These patients, however, represent a very small subset of patients with DGE.

The DGE rate in this series is lower than most other institutional experiences reported in the literature, such as the series by Welsch et al[29] in which a DGE rate of 44.5% was recorded. While most operative features, such as rate of vascular reconstruction, operative time, estimated blood loss, and patient co-morbidities appear similar to our series, we believe the low rate in this series is due largely to the uniformity of surgical approach within our cohort. All cases were performed by a single surgeon in a consistent manner utilizing a pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy with hand-sewn antecolic enteric anastomoses. While we cannot conclude that any one particular technique leads to lower rates of DGE, this series does demonstrate that consistency and experience over time with a specific method can allow it to be safely performed with acceptable outcomes.

Because of the association between pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess formation with DGE in this series as well as others, efforts to reduce morbidity of these common post-operative complications should continue. If patients identified as higher risk for POPF or abscess formation are the same ones identified as higher risk for DGE development, perhaps these patients may benefit from specific treatment approaches, such as prophylactic intraoperative placement of nasojejunal tubes or gastrojejunostomy tubes. Anticipating DGE in patients may also allow providers to plan for potential delays in recovery, individualize patient care, and improve allocation of resources (such as transitional care) to high-risk patients. We applied the FRS to our study population in order to determine whether a higher score correlated with increased risk of DGE. While on univariate analysis, a moderate to high FRS correlated with development of DGE, on multivariate analysis, a moderate-high FRS did not predict greater likelihood of DGE development postoperatively. However, the authors believe that further evaluation of the FRS in larger studies or in a prospective manner is warranted to truly determine if this score can aid in identifying patients with DGE.

Limitations of the current study include its retrospective nature and a relatively small cohort of patients with DGE. Strengths of this study include the homogeneity of the study population and the perioperative care. The patients were all operated on in a largely uniform manner (pylorus-preserving resection, antecolic reconstruction) and treated similarly post-operatively (no nasogastric decompression tubes, standardized postoperative care plans, etc.). Furthermore, no patients were excluded from this study and detailed post-operative data up to at least 90 d post-operatively is available for each of our patients. In this homogenous population, we identified the presence of postoperative fistula as the only predictor for DGE. Furthermore, w were able to demonstrate an association between moderate/high FRS and clinically significant DGE, suggesting a potential role of this score in predicting clinically significant DGE as well as POPF formation.

In summary, although DGE occurred in less than 20% of patients undergoing PD, it was associated with significantly higher complication rates, longer hospital stay, and increased healthcare utilization postoperatively. Patients with a high risk for pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess formation are at higher risk for developing DGE. Anticipating DGE in patients following PD is important and may allow providers to plan for potential delays in recovery, individualize patient care, and improve allocation of resources to high-risk patients.

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) remains one of the most frequent complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), affecting 15%-30% of patients post-operatively. DGE has been associated with increased hospital stay, higher readmission rates, and impaired quality of life.

The aims of this study were to examine a patient database and: (1) determine the incidence of DGE; (2) assess potentially associated risk factors for DGE; and (3) examine the impact of DGE on health care utilization.

DGE occurred in less than 20% of patients undergoing PD. It was associated with significantly higher complication rates, longer hospital stay, and increased healthcare utilization postoperatively. Patients with a high risk for pancreatic fistula or intra-abdominal abscess formation were at higher risk for developing DGE.

Anticipating DGE in patients following PD is important and may allow providers to plan for potential delays in recovery, individualize patient care, and improve allocation of resources to high-risk patients.

It is a well written manuscript analyzing the DGE in PF. All the analyses are well explained and supported with facts.

| 1. | Schmidt CM, Turrini O, Parikh P, House MG, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, Howard TJ, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Effect of hospital volume, surgeon experience, and surgeon volume on patient outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-institution experience. Arch Surg. 2010;145:634-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Kaufman HS, Coleman J. One hundred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without mortality. Ann Surg. 1993;217:430-435; discussion 435-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (33)] |

| 3. | Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg. 1995;130:295-299; discussion 299-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lieberman MD, Kilburn H, Lindsey M, Brennan MF. Relation of perioperative deaths to hospital volume among patients undergoing pancreatic resection for malignancy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:638-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 5. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248-257; discussion 257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1357] [Cited by in RCA: 1393] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 6. | Büchler MW, Friess H, Wagner M, Kulli C, Wagener V, Z’Graggen K. Pancreatic fistula after pancreatic head resection. Br J Surg. 2000;87:883-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsao JI, Rossi RL, Lowell JA. Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Is it an adequate cancer operation. Arch Surg. 1994;129:405-412. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Gouma DJ, Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Obertop H. The standard diagnostic work-up and surgical treatment of pancreatic head tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka M. Gastroparesis after a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Today. 2005;35:345-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahmad SA, Edwards MJ, Sutton JM, Grewal SS, Hanseman DJ, Maithel SK, Patel SH, Bentram DJ, Weber SM, Cho CS. Factors influencing readmission after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a multi-institutional study of 1302 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:529-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Berge Henegouwen MI, van Gulik TM, DeWit LT, Allema JH, Rauws EA, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy versus pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of 200 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:373-379. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lin PW, Lin YJ. Prospective randomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1999;86:603-607. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Eshuis WJ, van Dalen JW, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Route of gastroenteric reconstruction in pancreatoduodenectomy and delayed gastric emptying. HPB (Oxford). 2012;14:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oida T, Mimatsu K, Kano H, Kawasaki A, Fukino N, Kida K, Kuboi Y, Amano S. Antecolic and retrocolic route on delayed gastric emptying after MSSPPD. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1274-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Paraskevas KI, Avgerinos C, Manes C, Lytras D, Dervenis C. Delayed gastric emptying is associated with pylorus-preserving but not classical Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy: a review of the literature and critical reappraisal of the implicated pathomechanism. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5951-5958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park YC, Kim SW, Jang JY, Ahn YJ, Park YH. Factors influencing delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:859-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miedema BW, Sarr MG, van Heerden JA, Nagorney DM, McIlrath DC, Ilstrup D. Complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Current management. Arch Surg. 1992;127:945-949; discussion 949-950. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2460] [Article Influence: 129.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | United States Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 4.03. 2010;. |

| 20. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 981] [Article Influence: 70.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Mack LA, Kaklamanos IG, Livingstone AS, Levi JU, Robinson C, Sleeman D, Franceschi D, Bathe OF. Gastric decompression and enteral feeding through a double-lumen gastrojejunostomy tube improves outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2004;240:845-851. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Wollman B, D’Agostino HB, Walus-Wigle JR, Easter DW, Beale A. Radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical gastrostomy: an institutional evaluation and meta-analysis of the literature. Radiology. 1995;197:699-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Braga M, Gianotti L, Gentilini O, Parisi V, Salis C, Di Carlo V. Early postoperative enteral nutrition improves gut oxygenation and reduces costs compared with total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:242-248. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Abunnaja S, Cuviello A, Sanchez JA. Enteral and parenteral nutrition in the perioperative period: state of the art. Nutrients. 2013;5:608-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Trujillo EB, Young LS, Chertow GM, Randall S, Clemons T, Jacobs DO, Robinson MK. Metabolic and monetary costs of avoidable parenteral nutrition use. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1999;23:109-113. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Parmar AD, Sheffield KM, Vargas GM, Pitt HA, Kilbane EM, Hall BL, Riall TS. Factors associated with delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15:763-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sato G, Ishizaki Y, Yoshimoto J, Sugo H, Imamura H, Kawasaki S. Factors influencing clinically significant delayed gastric emptying after subtotal stomach-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2014;38:968-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Welsch T, Borm M, Degrate L, Hinz U, Büchler MW, Wente MN. Evaluation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definition of delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy in a high-volume centre. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1043-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Cecka F, Mylonas KS, Orii T S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ