Published online Sep 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i9.627

Peer-review started: January 20, 2016

First decision: February 15, 2016

Revised: July 6, 2016

Accepted: July 20, 2016

Article in press: July 22, 2016

Published online: September 27, 2016

Processing time: 250 Days and 15.8 Hours

To evaluate the effectiveness of human fibrinogen-thrombin collagen patch (TachoSil®) in the reinforcement of high-risk colon anastomoses.

A quasi-experimental study was conducted in Wistar rats (n = 56) that all underwent high-risk anastomoses (anastomosis with only two sutures) after colectomies. The rats were divided into two randomized groups: Control group (24 rats) and treatment group (24 rats). In the treatment group, high-risk anastomosis was reinforced with TachoSil® (a piece of TachoSil® was applied over this high-risk anastomosis, covering the gap). Leak incidence, overall survival, intra-abdominal adhesions, and histologic healing of anastomoses were analyzed. Survivors were divided into two subgroups and euthanized at 15 and 30 d after intervention in order to analyze the adhesions and histologic changes.

Overall survival was 71.4% and 57.14% in the TachoSil® group and control group, respectively (P = 0.29); four rats died from other causes and six rats in the treatment group and 10 in the control group experienced colonic leakage (P > 0.05). The intra-abdominal adhesion score was similar in both groups, with no differences between subgroups. We found non-significant differences in the healing process according to the histologic score used in both groups (P = 0.066).

In our study, the use of TachoSil® was associated with a non-statistically significant reduction in the rate of leakage in high-risk anastomoses. TachoSil® has been shown to be a safe product because it does not affect the histologic healing process or increase intra-abdominal adhesions.

Core tip: Anastomotic leakage is one of the most important complications in gastrointestinal surgery. We have performed a pioneering risk anastomosis procedure, carried out with a high risk of leakage, to test the use of thrombin and fibrinogen patch for the reinforcement and prevention of potential leakage. We obtained a significant reduction in the mortality rate without adding comorbidity. Patch application is simple and does not exceed operating time, and its use can be extremely helpful in emergency surgery or special situations that provide a high possibility of anastomosis dehiscence.

- Citation: Suárez-Grau JM, Bernardos García C, Cepeda Franco C, Mendez García C, García Ruiz S, Docobo Durantez F, Morales-Conde S, Padillo Ruiz J. Fibrinogen-thrombin collagen patch reinforcement of high-risk colonic anastomoses in rats. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(9): 627-633

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i9/627.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i9.627

Anastomotic leakage is a severe post-operative complication that can threaten a patient’s life. It has a mean incidence in the published literature of 4%-8%, and its mortality can reach up to 22%[1,2]. Several methods have been used to attempt to reduce anastomotic leakage associated with colonic surgery, with diverse results. As some authors have reported, staplers are the only method that maintains the incidence of anastomotic leakage under 10%[3]. Other authors have used glues and tissue sealants to reinforce the suture. Cyanoacrylates and fibrin glues are most often used, with varying results in the literature; some studies state that the use of cyanoacrylates and fibrin sealants in this kind of surgery is both efficient and advantageous[4,5], while others have failed to demonstrate such benefits[6]. Few studies have analyzed other materials, such as TachoSil®, a human fibrinogen and thrombin patch. TachoSil® contains human fibrinogen, human thrombin, and the following excipients: Equine collagen, human albumin, riboflavin (E101), sodium chloride, sodium citrate (E331), and L-arginine-hydrochloride. TachoSil® is indicated in adults as a supportive treatment in surgery for the improvement of hemostasis, the promotion of tissue sealing, and for suture support in vascular surgery where standard techniques are insufficient. Experimental studies have tried to assess if this product can improve the results of colonic anastomoses, with diverse results[7-10]. An important aspect of this topic is the definition of high-risk anastomoses. Tebala et al[5] defined this kind of anastomoses as including emergency surgery, ischemic or inflammatory tissues, esophagus or extraperitoneal rectus, and immunosuppression.

We hypothesized that colonic anastomosis carried out under poor conditions can be improved with the use of TachoSil® by decreasing anastomotic leakage and its complications.

A prospective, comparative, semi-experimental study in animals was conducted to analyze the effects of the application of a human fibrinogen-thrombin patch (TachoSil®) over high-risk anastomosis sites. The hypothesis was that this product would decrease the incidence and severity of colonic leakage. We compared the results with a control group in which there was only high-risk anastomosis. The study was carried out under the conditions established by the Helsinki statement, which regulates the terms and conditions for animal experiments. There was no competing interest for any of the authors. The authors did not receive any grant or sponsorship for this study. Materials were donated by the Department of Surgery of the University Hospital of Virgen del Rocío and Riotinto Hospital.

This study was performed on 56 white Wistar rats of both sexes weighing between 250 g and 350 g. Animals were divided into two groups (control group and treatment group), each consisting of 28 individuals. High-risk anastomosis was performed in all rats. A piece of fibrinogen-thrombin sealant was added that covered the entire anastomosis site in the treatment group.

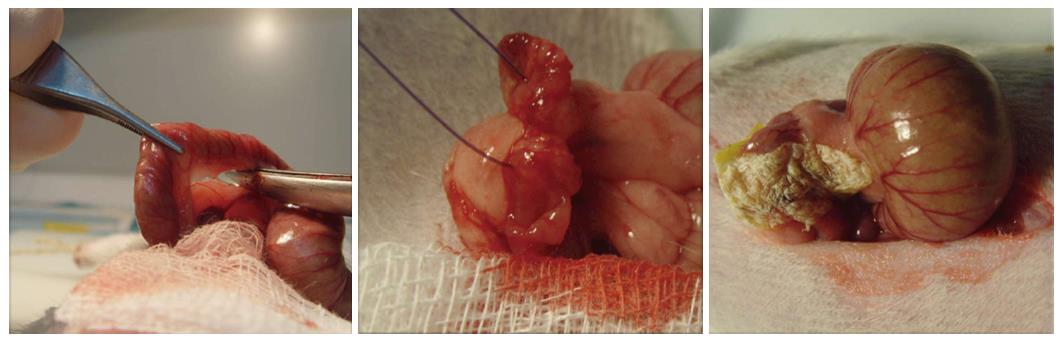

Anesthesia was induced with intraperitoneal ketamine (20 mg/kg), after which a laparotomy was performed. We then performed a partial colectomy of 2-3 cm just after the cecum, which was closed with an anastomosis with only two stitches of 4-0 monocryl in the mesenteric and anti-mesenteric borders of the colon. In addition, a 2 cm × 2 cm piece of TachoSil® was applied over the anastomosis, with light compression using small, wet gauze in the treatment group. Each piece was lightly wetted with 0.9% saline. The gauze was gently removed and the anastomosis site checked after 5 min to ensure the TachoSil® was in the proper location. The laparotomy was closed with 3-0 vicryl suture in a simple continuous suture for the muscle plane and 3-0 silk in a simple interrupted suture for the skin (Figure 1).

The early deceased animals underwent necropsy in order to establish the cause of death. The survivors were euthanized at 15 and 30 d post-operatively after a randomized process. During necropsy, the formation of intra-abdominal adhesions was quantified with a numeric scale (Table 1) to compare both groups at 15 and 30 d post-operatively. In all animals, colonic anastomosis was retrieved to analyze the histopathologic healing process according to the Biert scheme (Table 2), which analyzed nine parameters. The histologic analysis, using hematoxylin and eosin staining, was performed by a pathologist blinded for the two groups.

| Adhesive score |

| 0: No adhesions |

| 1: Extremely soft adhesions |

| 2: Stronger adhesions, but dissectible with dull dissection |

| 3: Stronger adhesions only dissectible with sharpen tools |

| 4: Stenosis |

| Parameters | Score | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Necrosis | No | Small patches | Large patches | Massive |

| PMNs | Normal | Slightly increased | Strong infiltration | Massive infiltration |

| Lymphocytes | Normal | Slightly increased | Strong infiltration | Massive infiltration |

| Macrophages | Normal | Slightly increased | Strong infiltration | Massive infiltration |

| Edema | No | Slight | Strong | Massive |

| Epithelium | Glandular normal | Cubic normal | Cubic incomplete | Absent |

| Submucosa-muscular | Good bridges | Mild bridges | Few bridges | Bridges absent |

| Angiogenesis | Extensive | Strong | Slight | Absent |

| Fibrosis | Extensive | Strong | Slight | Absent |

The program used for statistical analysis was SPSS v16 for Windows, and the statistical review was performed by a biomedical statistician. Numerical results were analyzed using means and standard deviations. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess survival. Leakage incidence was analyzed with the χ2 test for dichotomous variables. The intra-abdominal adhesion score was compared between groups with the Mann-Whitney test, as the variable was qualitative. The histopathologic healing process was analyzed with the Student’s t-test, with sub-analysis performed with the Mann-Whitney test when necessary. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

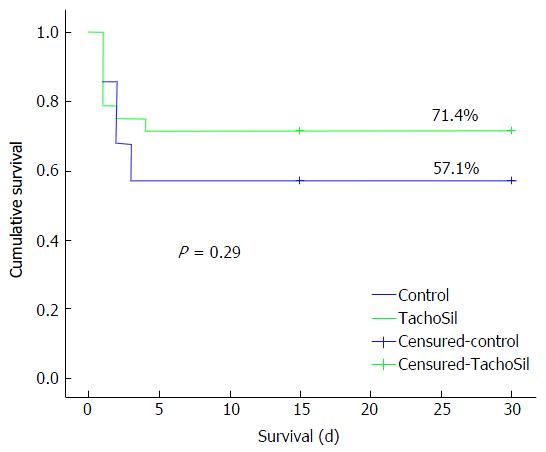

The number of events, defined as death as a consequence of colonic leakage, was 10 (35.7%) in the control group and 6 (21.4%) in the TachoSil® group. All deaths happened before the fourth post-operative day. Four animals in both groups died due to other causes, namely hemorrhage, post-anesthesia and bowel obstruction, with no relation to the experimental study. The mean survival per group was 19.5 ± 2.6 (control) and 23.7 ± 2.2 d (TachoSil®). With these results, the overall survival was 57.14% and 71.4% in the control and TachoSil® groups, respectively (P = 0.29) (Figure 2), with no significant differences between the groups.

The results are shown in Table 3. We performed comparisons according to both the time (15 d vs 30 d) and group [control (16 rats) vs TachoSil® (20 rats)]. Distribution of animals sacrificed: control-15 d = 9 rats, control-30 d = 7 rats; TachoSil-7 d = 10 rats, TachoSil-15 d = 10 rats. The adhesion score was significantly different when comparing all groups according to the time, showing a much better score in animals euthanized at day 30. However, no differences were found at day 15 or day 30 when comparing groups.

| Mann-Whitney mean ranges | P value | |

| Survivors (15 d vs 30 d) | 25.11 vs 11.12 | 0.0012 |

| Control (15 d vs 30 d) | 10.53 vs 5.5 | 0.017 |

| TachoSil (15 d vs 30 d) | 14.75 vs 6.25 | 0.001 |

| Control vs TachoSil (15 d) | 9.5 vs 10.45 | 0.685 |

| Control vs TachoSil (30 d) | 9.71 vs 8.50 | 0.584 |

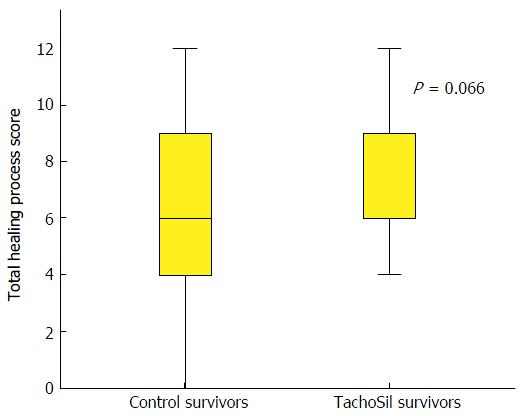

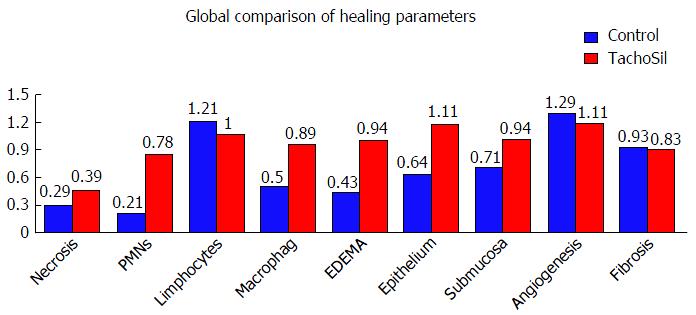

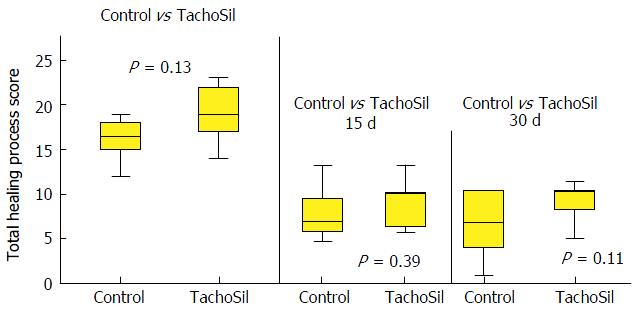

Healing of the anastomoses was analyzed following the Biert scheme. The global results are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Only four parameters (Table 4) showed significant differences between the control and TachoSil® groups with the Student’s t-test, and were always worse in the TachoSil® group polymorphonuclear cells 0.21 ± 0.42 vs 0.78 ± 0.64, P = 0.01; macrophages 0.50 ± 0.65 vs 0.89 ± 0.47, P = 0.026; oedema 0.43 ± 0.64 vs 0.94 ± 0.63, P = 0.017; and epithelium regeneration 0.64 ± 0.92 vs 1.11 ± 0.58, P = 0.031. The rest of parameters were similar between groups.

| Control | TachoSil | P value | |

| PMNs | 0.21 ± 0.42 | 0.78 ± 0.64 | 0.010 |

| Macrophages | 0.50 ± 0.65 | 0.89 ± 0.47 | 0.026 |

| Edema | 0.43 ± 0.64 | 0.94 ± 0.63 | 0.017 |

| Epithelium regeneration | 0.64 ± 0.92 | 1.11 ± 0.58 | 0.031 |

When we applied the total score for this analysis, defined as the sum of all values of each parameter, we found nearly significant differences between groups. Among all survivors, the control group had a mean total healing score of 6.21 ± 3.21, whereas the TachoSil® group had a mean of 8 ± 2.05 (P = 0.066) (Figure 3).

Sub-analysis of this total healing process score according to the post-operative day (15 and 30 d) did not show statistically significant differences, but we did see a trend towards a worsened healing process in the TachoSil® group, especially at the end of the period. On days 15 and 30, the results were 7.5 vs 9.5 (P = 0.39) and 6.17 vs 9.9 (P = 0.112) in the control group vs the TachoSil® group, respectively (mean ranges) (Figure 5). There were no differences when the analysis was performed between groups (global analysis) (7.15 vs 10.75; P = 0.13).

Colonic anastomosis failure can be a life threatening complication following colonic surgery. Over time, great efforts have been made to improve the results of this procedure and define the risk factors for anastomosis failure[1,2,11]. Systemic factors (such as diabetes and steroid use) and local factors (such as radiotherapy and tension or hemorrhage in the suture) can lead to a poor result in the healing process of the colon[12-14]. The period in which a leak occurs is usually between days 5 and 6 post-operation. Before this period, the strength of anastomosis is mainly held by the suture, but after day 5 or 6 the healing process of the colonic wall, especially with regards to the collagen formation, is most important, as the suture material loses efficacy at that time. A variety of products[6,15-19] have been used to reinforce intestinal anastomoses (e.g., cyanoacrylate, fibrin sealants, amniotic, collagen and dura mater membranes, and mechanical staplers), all with different results. The application of a fibrinogen and thrombin patch over colonic anastomoses is a relatively new idea[7]. Some authors[19,20] used the classical cecal puncture model to define high-risk anastomosis, thereby providing the sepsis model[20-24]. To date, there has not been any consensus regarding the definition of high-risk anastomosis and, to our knowledge, there have been few studies that have examined the application of TachoSil® over colonic anastomoses[7-10,20-24], with only one carried out using a high-risk anastomosis[10]. Although these studies showed the method to be safe and feasible, some results have been controversial; Ozel et al[7] showed that this product increased the inflammatory reaction and led to a worsened healing process with less mechanical strength. In contrast, Stumpf et al[9] found that it led to a better histopathologic healing process as a consequence of the decrease in suture material in the anastomotic line and that a suture-free anastomosis is reliable. Nordentoft et al[8,22] studied this product applied over normal small-bowel anastomoses and found no differences in the mechanical strength, degree of stenosis, or healing process, with the incidence of anastomotic leakage also being similar between groups. In our study, we noted an evident reduction of anastomotic leakage incidences (31.7% vs 21.4% in control and TachoSil® groups, respectively), but these differences were not significant (P = 0.29). Even when a potentially injurious agent such as 5-fluorouracil is used, it has been verified that applying anastomosis TachoSil® confers greater resistance by acting as a protective agent[24]. In a study using mice, Pantelis et al[10] achieved a statistically significant difference in the lethality and leakage rates in the group that received TachoSil®, as well as finding that its use did not increase the formation of intra-abdominal adhesions. They did not find any differences between groups. In studies that analyzed the use of TachoSil® in bowel anastomoses, Nordentoft et al[8] reported no differences between groups. In contrast, Ozel et al[7] noted that TachoSil® increased the formation of peri-anastomotic adhesions. Regarding the histopathologic healing process, we found neither advantages nor disadvantages when TachoSil® was applied. However, when we analyzed this process with both individual and global scores, some individuals were statistically different with regards to group (control or treatment), but when the global score was compared, no differences were observed. Some authors, such as Ozel, affirmed that if TachoSil® is used, the neutrophilic granulocyte count can increase, and this carries a worsened prognosis for healing as a result of excessive metalloproteinases. These results were also observed by van der Ham et al[21]. In contrast, Pantelis observed that if TachoSil® is applied in high-risk anastomosis, an improvement in the healing process can be observed. In our study, the healing process is exacerbated and inflammatory parameters were increased when TachoSil® was used, compared to the control group. However this does not affect the creation of useful anastomosis, only higher growth of tissue in the area where it is applied, accompanied by obvious signs of inflammation. This has not affected the result of the study and the rate of leakage has decreased, therefore we believe that a stronger healing process is useful in reinforcing the consistency of anastomosis.

We think that, despite the worsened healing in some individual parameters in the TachoSil® group, the improvement in leak incidence can be explained by the sealant effect of the collagen patch (i.e., the mechanical sealant achieved by this sponge, which is a well-established effect of this product)[7,8,23].

In conclusion, our study showed that the application of TachoSil® led to a non-statistically significant decrease in both mortality and anastomotic leakage rates. Furthermore, the use of this product did not affect the histopathologic healing process or increase the formation of adhesions, and so it can be regarded as a very safe product. We focused on the importance of the mechanical effect of TachoSil® in sealing the anastomosis gap. The use of TachoSil® is not justified in routine colonic surgery due to the low colonic anastomotic leakage rates in those procedures. Although we demonstrated that TachoSil® does not decrease the complication rate in high-risk anastomoses, based on the controversial data existing in the literature, we recommend that clinical studies should be performed to clarify this topic, as it may have potentially important effects in surgery.

This is an experimental study to test the absorbable product TachoSil® in risk anastomosis in rats. The hypothesis to be tested is decreasing anastomotic leaks using this product. The triple-blind comparative results confirm a decrease in leakage anastomotic.

The main frontier of the study is the reduction of anastomosis leakage in anastomosis with risk factors.

Decreasing the rate of leaks in anastomosis using an absorbable sheet on the anastomosis when the procedure was performed in high-risk conditions.

The results can be applied in digestive surgery (i.e., intestinal and colorectal anastomosis), especially in emergency surgeries and patients with high comorbidities.

This manuscript showed the potential application of TachoSil® in colonic sutures after surgery. The study was straight-forward and rational. The application apparently has some merits.

| 1. | Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 861] [Cited by in RCA: 826] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Andersson M, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:462-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Smith LE. Anastomosis with EEA stapler after anterior colonic resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;1:160–167. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Coover HW, Joyner FB, Sheareer NH, Wicner TH. Chemistry and performance of cyanocryalate adhesive. J Soc Plast Enf. 1959;15:413-417. |

| 5. | Tebala GD, Ceriati F, Ceriati E, Vecchioli A, Nori S. The use of cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in high-risk intestinal anastomoses. Surg Today. 1995;25:1069-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nursal TZ, Anarat R, Bircan S, Yildirim S, Tarim A, Haberal M. The effect of tissue adhesive, octyl-cyanoacrylate, on the healing of experimental high-risk and normal colonic anastomoses. Am J Surg. 2004;187:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ozel SK, Kazez A, Akpolat N. Does a fibrin-collagen patch support early anastomotic healing in the colon? An experimental study. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:233-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nordentoft T, Rømer J, Sørensen M. Sealing of gastrointestinal anastomoses with a fibrin glue-coated collagen patch: a safety study. J Invest Surg. 2007;20:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stumpf M, Junge K, Rosch R, Krones C, Klinge U, Schumpelick V. Suture-free small bowel anastomoses using collagen fleece covered with fibrin glue in pigs. J Invest Surg. 2009;22:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pantelis D, Beissel A, Kahl P, Wehner S, Vilz TO, Kalff JC. The effect of sealing with a fixed combination of collagen matrix-bound coagulation factors on the healing of colonic anastomoses in experimental high-risk mice models. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:1039-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peeters KC, Tollenaar RA, Marijnen CA, Klein Kranenbarg E, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, van de Velde CJ. Risk factors for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 12. | Tagart RE. Colorectal anastomosis: factors influencing success. J R Soc Med. 1981;74:111-118. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Goligher JC, Graham NG, De Dombal FT. Anastomotic dehiscence after anterior resection of rectum and sigmoid. Br J Surg. 1970;57:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Daly JM, Vars HM, Dudrick SJ. Effects of protein depletion on strength of colonic anastomoses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;134:15-21. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Eryilmaz R, Samuk M, Tortum OB, Akcakaya A, Sahin M, Goksel S. The role of dura mater and free peritoneal graft in the reinforcement of colon anastomosis. J Invest Surg. 2007;20:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schreinemacher MH, Bloemen JG, van der Heijden SJ, Gijbels MJ, Dejong CH, Bouvy ND. Collagen fleeces do not improve colonic anastomotic strength but increase bowel obstructions in an experimental rat model. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:729-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Elemen L, Sarimurat N, Ayik B, Aydin S, Uzun H. Is the use of cyanoacrylate in intestinal anastomosis a good and reliable alternative? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:581-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nandakumar G, Richards BG, Trencheva K, Dakin G. Surgical adhesive increases burst pressure and seals leaks in stapled gastrojejunostomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:498-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Byrne DJ, Hardy J, Wood RA, McIntosh R, Hopwood D, Cuschieri A. Adverse influence of fibrin sealant on the healing of high-risk sutured colonic anastomoses. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1992;37:394-398. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Uludag M, Citgez B, Ozkaya O, Yetkin G, Ozcan O, Polat N, Isgor A. Effects of amniotic membrane on the healing of normal and high-risk colonic anastomoses in rats. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:809-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | van der Ham AC, Kort WJ, Weijma IM, van den Ingh HF, Jeekel J. Effect of fibrin sealant on the healing colonic anastomosis in the rat. Br J Surg. 1991;78:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nordentoft T. Sealing of gastrointestinal anastomoses with fibrin glue coated collagen patch. Dan Med J. 2015;62:pii: B5081. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Tallón-Aguilar L, Lopez-Bernal Fde A, Muntane-Relat J, García-Martínez JA, Castillo-Sanchez E, Padillo-Ruiz J. The use of TachoSil as sealant in an experimental model of colonic perforation. Surg Innov. 2015;22:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sabino FD, Campos CF, Caetano CE, Trotte MN, Oliveira AV, Marques RG. Effects of TachoSil and 5-fluorouracil on colonic anastomotic healing. J Surg Res. 2014;192:375-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kok VC, Tomizawa M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Li D