Published online Jun 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.467

Peer-review started: March 7, 2016

First decision: March 22, 2016

Revised: April 4, 2016

Accepted: April 14, 2016

Article in press: April 15, 2016

Published online: June 27, 2016

Processing time: 108 Days and 11.9 Hours

Hemobilia is an uncommon and potential life-threatening condition mainly due to hepato-biliary tree traumatic or iatrogenic injuries. Spontaneously ruptured aneurysm of the hepatic artery is seldom described. We report the case of an 89-year-old woman presenting with abdominal pain, jaundice and gastrointestinal bleeding, whose ultrasound and computed tomography revealed a non-traumatic, spontaneous aneurysm of the right hepatic artery. The oeso-gastro-duodenoscopy and colonoscopy did not reveal any bleeding at the ampulla of Vater, nor anywhere else. Selective angiography confirmed the diagnosis of hepatic artery aneurysm and revealed a full hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery. The patient was successfully treated by selective embolization of microcoils. We discuss the etiologies of hemobilia and its treatment with selective embolization, which remains favored over surgical treatment. Although aneurysm of the hepatic artery is rare, especially without trauma, a high index of suspicion is needed in order to ensure appropriate treatment.

Core tip: Non-traumatic aneurysm of the hepatic artery leading to hemobilia as the source of gastrointestinal bleeding may be subtle to recognize, not only because of its low incidence but also because of its inconsistent clinical signs. These aneurysms are more commonly seen after a traumatic event on the biliary tree, however in rare cases, it occurs spontaneously, mainly in the settings of vascular degeneration and chronic gallbladder inflammatory disease. Moreover, the hepatic artery is known for multiple anatomical variants, some of which are rare. Our patient presented with both uncommon conditions and was successfully treated with micro-coils embolization.

- Citation: Vultaggio F, Morère PH, Constantin C, Christodoulou M, Roulin D. Gastrointestinal bleeding and obstructive jaundice: Think of hepatic artery aneurysm. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(6): 467-471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i6/467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.467

Bleeding into the biliary tree was first described by Glisson[1] in 1654 and later named hemobilia by Sandblom[2] in 1948. Its classical triad - Quincke’s triad - includes colicky right upper quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice and gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and is seen in 20% of hemobilia[3]. Only about 10% of cases of hemobilia are secondary to a ruptured aneurysm of the hepatic artery[4], which is located in intrahepatic branches in 20%[5,6]. The occurrence of hemobilia consecutive to a spontaneously ruptured aneurysm of the hepatic artery remains uncommon and its treatment modalities are not evidence-based, although supra-selective embolization seems to overcome surgery in the management[7]. This case represents not only a rare case of spontaneous aneurysm of the hepatic artery but also illustrates an anatomical variant of its origin. Our patient was successfully treated with supra-selective microcoils embolization.

An 89-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with increased epigastric and hyponchondrium colic since one month, associated with inappetence, nausea, vomiting and several episodes of hematemesis and hematochezia for the last 24 h. She did not have temperature during that period of time. She is known for an aorto-coronary bypass and four stents in 2001, as well as hypertension. Her current medication includes acetylsalicylic acid, amlodipine, atorvastatin, nicorandil and molsidomine. There is no history of trauma, and she is not known for hepato-biliary or gastrointestinal tract disorders.

At admission, she was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. She presented with mild scleral icterus. There was no abdominal tenderness. On rectal examination, no traces of blood were found. The laboratory tests showed mild anemia with a hemoglobin count of 98 g/L (normal 117-157 g/L), a white blood cell count (WBC) of 11 g/L (normal 4-10 g/L), cytolysis and cholestasis with aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) 111 U/L (normal < 35 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) 103 U/L (normal < 35 U/L), gamma-GT 247 U/L (normal < 40 U/L), alkaline phosphatase 473 U/L (normal < 130 U/L), total and direct bilirubin 20 and 14 μmol/L respectively (normal < 17 and < 5 μmol/L respectively).

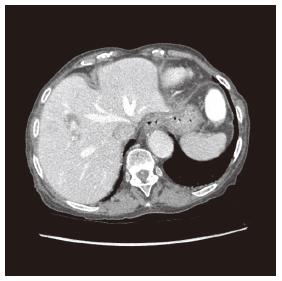

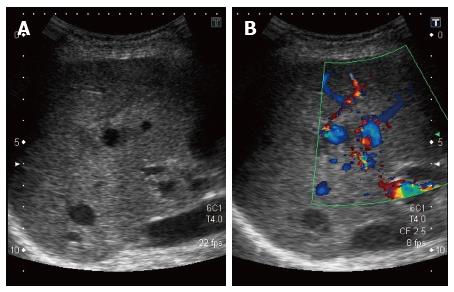

The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 10 mm × 6 mm aneurysm of a branch of the right hepatic artery irrigating segment VIII, and a lithiasic gallblader with thickened walled (Figure 1), without signs of cholecystitis. The ultrasound (US) revealed a thrombosed aneurysm of the hepatic artery with ectasia of the upward biliary tree (Figure 2).

The upper endoscopy did not show evidence of blood at the ampulla of Vater, but revealed signs of uncomplicated gastritis. Colonoscopy showed sigmoidal diverticulosis, without any source of active bleeding.

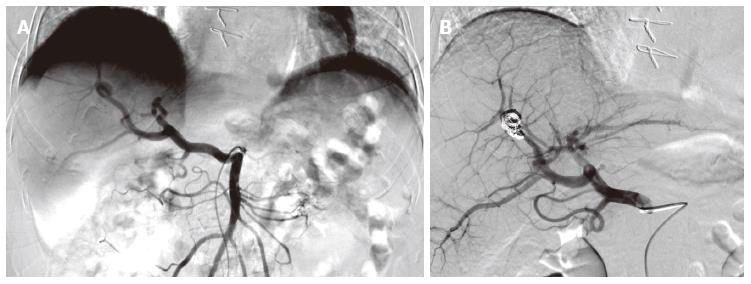

Her hemoglobin continued to drop to 83 g/L, necessitating the transfusions of two units of blood. Since our only source of potential bleeding was this aneurysm, we practiced an angiography by catheterization of the right femoral artery with a 5-French catheter. We performed a supra-selective catheterization of the right hepatic artery with a 3-French microcatheter and embolization of the aneurysm with four 4 mm × 37 mm and two 8 mm × 140 mm microcoils. During the procedure, we realized that the hepatic artery was originating directly from the superior mesenteric artery. Thus, the aneurysm was located on the right branch of this particular hepatic artery (Figure 3).

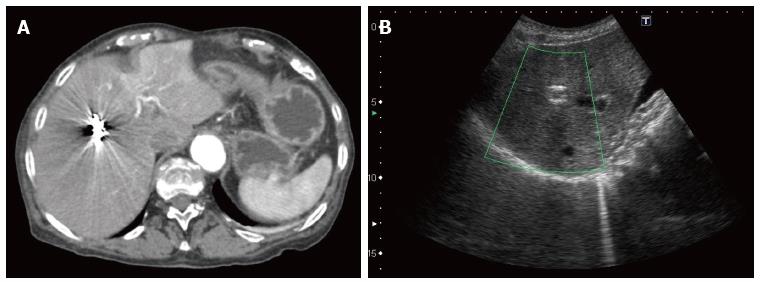

The patient was dismissed two days later without any complications. There were no recurrences at the follow-up CT and US, at day two and thirty respectively (Figure 4).

Two months later, the patient returned to the emergency department with paroxysmal right upper quadrant colicky abdominal pain and jaundice. No blood loss was observed. She was hemodynamically stable and her physical exam did not reveal any abdominal pain upon palpation, nor fever at 36.8 °C. Her laboratory tests exhibited anemia with a hemoglobin at 96 g/L, an inflammatory syndrome with a WBC of 40 g/L and a C-reactive protein of 117 mg/L, as well as cholestasis and cytolysis (ASAT 167 U/L, ALAT 92 U/L, gamma-GT 330 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 912 U/L, total and direct bilirubin 84 and 75 μmol/L). She benefited from an antibiotic therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole for 72 h, with a shift to ciprofloxacine and metronidazole per os for 2 wk. The cholangiography-MRI showed no traces of choledocolithiasis, but a dilated principal and intrahepatic bile ducts, a thick gallbladder wall with sludge and cholelithiasis. There were no signs of recurrent bleeding at the site of micro-embolization, nor any abscess (Figure 4). During hospitalization, she evolved without any complications. Both pain and jaundice resolved and her laboratory tests returned towards normal values before she was dismissed at day seven.

The most common causes of hemobilia are due to iatrogenic complications after diagnostic or therapeutic hepatobiliary procedures, and accounts for more than half to two thirds of the cases[3,8], while non-traumatic causes include aneurysmal disease, which accounts for 10%, and is mainly seen in the setting of atherosclerosis, gallbladder inflammatory diseases, hepatobiliary tract infections or neoplasia, and autoimmune systemic diseases such as juvenile polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis[3,9]. Our patient was known and treated for arterial disease, which might have played a predominant role in the physiopathology of her disease.

Although upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy is a crucial step in order to establish both diagnosis and treatment of an ongoing gastrointestinal bleeding, its ability in detecting active bleeding at the ampulla of Vater is only in about half of the patients with hemobilia[10,11]. Nevertheless, this procedure remains mandatory to rule out and treat other more frequent causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Angiography is now favored over surgery as the best procedure for diagnosing and treating hemobilia, although there is currently no gold standard established in the literature[12]. Angiography reveals more than 90% of sources of active bleeding[3,12], while its success rate in managing the bleeding is more than 80% with a good tolerance and minimal risks compared to surgery[3,12].

Although our patient presented a cholangitis, cholangiography-MRI at two months showed that the coils were in place and no recurrences had occurred. Since no signs of intraductal obstacle, extrinsic compression, or microlithiasis were found, we hypothesize that a blood clot migrated into the biliary tree, leading to cholangitis. The evolution with antibiotics was uneventful.

Our patient exhibited a relatively rare variant of full hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery (Figure 3), variant IX in Michels’ classification, which is seen in about 4.5% of the population[13]. Knowing that the hepatic artery is present in its classical anatomy in only 55%, it is crucial that the operator takes these specificities into account when performing the angiography and subsequent embolization.

In conclusion, ruptured aneurysm of the hepatic artery without trauma leading to hemobilia is a rare and life-threatening condition. Clinicians need a high index of suspicion in order to diagnose and treat it adequately. The first line treatment is now angiography and supra-selective embolization, as it has superseded surgical intervention.

An 89-year-old female with history of abdominal pain, inappetence, vomiting and several episodes of hematemesis and hematochezia.

The patient was jaundiced.

Bleeding gastro-duodenal ulcus; biliary tumor; Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

White blood cell 11 g/L, aspartate aminotransferase 111 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 103 U/L, gamma-GT 247 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 473 U/L, total bilirubin 20 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 14 μmol/L.

Ruptured aneurysm of the branch of the right branch of a full hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery.

Fluid challenge, blood transfusion, selective arteriography with selective microcoils embolization, antibiotherapy.

Hemobilia is a rare case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to arterio-biliary fistula.

Focusing on the clinical recognition of hemobila in this particular setting of gastrointestinal bleeding and a positive experience with selective angiography and embolization for diagnosis and treatment. It requires a high index of suspicion particularly in the absence of an established traumatic or iatrogenic event.

The authors demonstrated a rare case of spontaneous aneurysm of the right hepatic artery, and that the patient has been successfully treated by selective embolization of micro coils.

| 1. | Glisson F. London: O. Pullein 1654; . |

| 2. | Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948;24:571-586. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Green MH, Duell RM, Johnson CD, Jamieson NV. Haemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88:773-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Harlaftis NN, Akin JT. Hemobilia from ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1977;133:229-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Finley DS, Hinojosa MW, Paya M, Imagawa DK. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2005;35:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berenson MM, Freston JW. Intrahepatic artery aneurysm associated with hemobilia. A case report. Gastroenterology. 1974;66:254-259. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moodley J, Singh B, Lalloo S, Pershad S, Robbs JV. Non-operative management of haemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1073-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ryan MF, Murphy JP, Benjaminov O. Hemobilia due to idiopathic hepatic artery aneurysm: case report. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2002;53:149-152. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Liu TT, Hou MC, Lin HC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Life-threatening hemobilia caused by hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: a rare complication of chronic cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2883-2884. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Traversa G, Zippi M, Bruni A, Mancuso M, Di Stefano P, Occhigrossi G. A rare case of hemobilia associated with aneurysms of the celiac trunk, the hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. Endoscopy. 2006;38 Suppl 2:E5-E6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Curet P, Baumer R, Roche A, Grellet J, Mercadier M. Hepatic hemobilia of traumatic or iatrogenic origin: recent advances in diagnosis and therapy, review of the literature from 1976 to 1981. World J Surg. 1984;8:2-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Srivastava DN, Sharma S, Pal S, Thulkar S, Seith A, Bandhu S, Pande GK, Sahni P. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of hemobilia. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Catalano OA, Singh AH, Uppot RN, Hahn PF, Ferrone CR, Sahani DV. Vascular and biliary variants in the liver: implications for liver surgery. Radiographics. 2008;28:359-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kouraklis G, Naito Y S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL