Published online Jun 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.452

Peer-review started: February 2, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: March 5, 2016

Accepted: March 24, 2016

Article in press: March 25, 2016

Published online: June 27, 2016

Processing time: 139 Days and 17.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the long-term clinical and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic rectal resection (LRR) and the impact of conversion in patients with rectal cancer.

METHODS: An analysis was performed on a prospective database of 633 consecutive patients with rectal cancer who underwent surgical resection. Patients were compared in three groups: Open surgery (OP), laparoscopic surgery, and converted laparoscopic surgery. Short-term outcomes, long-term outcomes, and survival analysis were compared.

RESULTS: Among 633 patients studied, 200 patients had successful laparoscopic resections with a conversion rate of 11.1% (25 out of 225). Factors predictive of survival on univariate analysis include the laparoscopic approach (P = 0.016), together with factors such as age, ASA status, stage of disease, tumor grade, presence of perineural invasion and vascular emboli, circumferential resection margin < 2 mm, and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. The survival benefit of laparoscopic surgery was no longer significant on multivariate analysis (P = 0.148). Neither 5-year overall survival (70.5% vs 61.8%, P = 0.217) nor 5-year cancer free survival (64.3% vs 66.6%, P = 0.854) were significantly different between the laparoscopic group and the converted group.

CONCLUSION: LRR has equivalent long-term oncologic outcomes when compared to OP. Laparoscopic conversion does not confer a worse prognosis.

Core tip: Laparoscopic rectal resection (LRR) remains controversial in view of concerns over its long term oncological outcome and the adverse impact conversion may have on survival. Our retrospective study has demonstrated that LRR has equivalent long-term oncologic outcomes when compared to open surgery. Conversion was also found not to confer a worse prognosis.

- Citation: Tan WJ, Chew MH, Dharmawan AR, Singh M, Acharyya S, Loi CTT, Tang CL. Critical appraisal of laparoscopic vs open rectal cancer surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(6): 452-460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i6/452.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i6.452

Surgical management for rectal cancer remains challenging. With the advent of total mesorectal excision (TME) in rectal cancer surgery, local recurrence rates have improved significantly and there is an increasing rate of sphincter-saving surgery when technically and oncologically feasible. However, despite the use of pre- or post-operative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, local and distant tumor recurrence remains a concern.

While laparoscopic colectomy has established its oncologic equivalence compared to open surgery (OP) in colon cancer, laparoscopic rectal resection (LRR) for rectal cancer remains controversial. Although LRR has been shown to confer short-term benefits, in terms of blood loss, length of stay, recovery of bowel function, and cosmesis, concerns about the long-term oncologic outcomes persists[1-5]. The necessity for a TME creates a more difficult learning curve for LRR compared to a laparoscopic colectomy. There is also the need to achieve a balance between sphincter preservation without compromising the adequacy of the distal resection margin[6]. These challenges induce a higher rate of conversion compared to colonic resection[2] and a recent Cochrane review has noted that conversion rates in LRR can be as high as 35%[7]. This is an important concern as it has been suggested that conversion to OP after attempted LRR not only has higher morbidity, but may also adversely affect long-term oncologic outcomes[2,8-11]. Several publications have attempted to address this issue but the study populations often consisted of a mixture of patients with colon and rectal cancer[12-14]. This is suboptimal as the prognosis and recurrence pattern of colon and rectal cancer are distinctly different. There are few publications that address the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic conversion specifically in the context of rectal cancer[10,15,16].

Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the long-term clinical and oncological outcomes of LRR as well as the impact of laparoscopic conversion on the long-term oncological outcomes of patients with rectal cancer.

An analysis of a prospectively maintained database of 633 consecutive patients with rectal cancer who underwent surgical resection from January 2005 to December 2009 in the Department of Colorectal Surgery at Singapore General Hospital was performed. Patients who presented with recurrent cancer, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Familial Adenomatous Polyposis, or other polyposis syndromes were excluded. Data on patient demographics, pre-operative, operative, and post-operative course were collected prospectively and maintained in a database by a research assistant.

All cases were performed by consultant surgeons within the department. The decision for laparoscopic or open approach was left to the discretion of the individual surgeon.

For the laparoscopic approach, we preferred the medial approach with early mobilization, ligation and division of the inferior mesenteric artery at its origin after the ureter has been identified. The inferior mesenteric vein was ligated and divided at the inferior border of the pancreas. This was followed by mobilization of the left colon from the lateral sidewall, with mobilization of the splenic flexure if deemed necessary to achieve a tension free anastomosis. Total meso-rectal excision or wide meso-rectal excision up to at least 2 cm distal to the tumor was performed for all cases when feasible. Distal transection was performed using articulating staplers. The specimen is exteriorized via extension of the port sites with proximal transection performed extra-corporeally. Pneumoperitoneum is then re-established and intra-corporeal circular stapled anastomosis performed under direct vision.

OP was performed via a midline laparotomy or left iliac fossa incision as described in a previous publication[17].

Patients were compared in three groups: OP, laparoscopic surgery (LS), and converted laparoscopic surgery (CON) with their definitions as follows: (1) OP: Completion of surgical resection and anastomosis via midline laparotomy or left iliac fossa incision; (2) LS: Surgery accomplished using the laparoscopic technique as described above. Patients analyzed under the LS group included patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted surgery as described in a previous publication by our department[18]. These were patients who had vascular ligation and the majority of bowel mobilization was accomplished intra-corporeally via the laparoscopic approach with the following modifications: (a) extension of one port site wound or the utilization of a new wound to complete colonic mobilization and bowel transection for reasons such as the presence of adhesions, excessive tumor fixation, or uncertain tumor location; (b) extracorporeal rectal anastomosis due to technical difficulties such as a narrow pelvis, bulky tumor, or defective equipment; and (c) extension of wounds to repair the anastomosis due to leaks on testing after completion of a pure laparoscopic resection; (3) CON: The laparoscopic approach is aborted after insertion of ports and initial bowel mobilization. This can be due to the presence of dense adhesions, undiagnosed tumor invasion of surrounding organs, or trouble-shooting complications such as uncontrolled bleeding, bowel perforation, or injury of adjacent viscera such as ureters or small bowel. Conversion is also defined if the anastomosis requires a complete takedown and revision.

All cases were evaluated preoperatively by plain chest radiograph/computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and CT of the abdomen and pelvis. T-staging with an endo-rectal ultrasound was performed pre-operatively in clinical T1 and T2, mid and low rectal tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis was performed for all lower rectum tumors. Upper rectum is defined as 11-15 cm, middle rectum as 6-10 cm, and lower rectum as 0-5 cm from the anal verge. These measurements were recorded by the consultant surgeon after digital rectal examination and endoscopy. Disease staging according to the American Joint Committee Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual 7th Edition was adopted[19].

In our institution, a selective neoadjuvant chemoradiation policy is adopted based on data from previous publications that have consistently shown low local recurrence rates with oncologically adequate surgery alone[20-22]. If sphincter preservation with good margins can be performed after initial evaluation, neoadjuvant treatment is usually not routinely recommended in our local population. Neoadjuvant treatment is mainly performed in patients who present with a threatened circumferential resection margin, defined as within 2 mm of the circumferential resection margin based on pre-operative staging.

The neoadjuvant regimen consisted of long-course preoperative radiotherapy (45-50 Gy in 25-28 daily fractions over 5 wk) combined with 5-fluorouracil or oral capecitabine. Patients proceeded with surgical resection 6 to 8 wk after completion of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Decision for adjuvant chemotherapy was decided after discussion at a multi-disciplinary tumor board meeting.

Perioperative care for all patients was standardized using existing clinical care pathways.

Post-operatively, the patients were followed-up at three monthly intervals for the first two years, six monthly for the next three years, and then yearly thereafter. At each consultation, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were measured and full history and physical examination (including digital rectal examination) were performed. Colonoscopy was performed within six months of surgery if initial complete evaluation was not possible pre-operatively due to tumor obstruction or stenosis. Those who had an initial complete evaluation underwent colonoscopy at the first year follow up, and again at 3-yearly intervals post-operatively. Patients with suspicious symptoms and signs of rising CEA trend on follow-up will be evaluated earlier with colonoscopy and/or radiological imaging (including computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, bone scan, and positron emission tomography scans if applicable).

Local recurrence was defined as the first clinical, radiologic, and/or pathologic evident tumor of the same histological type, within the true pelvis, at the anastomosis or in the region of the anastomosis. Distant recurrence was defined as similar evidence of spread outside the primary tumor at sites including but not limited to the liver, lungs, bone, brain, and para-aortic region. Patients who were first diagnosed with local recurrence but later developed distant metastasis were classified under the local recurrence group. Mortality data and the cause of death were obtained from the Singapore Cancer Registry.

Short-term outcomes assessed included wound infections, post-operative ileus, anastomotic leaks, pneumonia, peri-operative cardiac events, duration of hospitalization, and 30-d mortality.

Long-term outcomes assessed included the occurrence of intestinal obstruction, incisional hernias, and the oncologic outcomes of local/distal recurrence.

Survival analysis was performed via the comparison of progression free survival and overall survival (OS).

All statistical analysis was performed by a qualified biostatistician. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were compared across the 3 groups using χ2 and t tests for categorical and continuous variables respectively. Distribution of selected short- and long-term outcomes among the patients undergoing surgery was compared using Fisher’s exact test. Comparison of the median duration of hospitalization was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test as it deviates from the Normality assumption.

OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Cancer-free survival (CFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of disease progression (local or distant relapse) or last follow-up. The 5-year OS and CFS were estimated using Kaplan Meier method and the survival curves were compared using log-rank tests. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, using variables found to be significant on univariate analysis, were used to estimate hazard ratios with their 95%CI. A significance level of 0.05 was chosen throughout. All analyses were performed using R 3.1.1 (2014, Vienna, Austria).

Six hundred and thirty-three patients underwent surgical resection for primary rectal cancers during the study duration. The demographic characteristics of the study population are illustrated in Table 1. Two hundred and twenty-five patients (35.5%) underwent attempted laparoscopic resection of the rectal tumor. Among these, 200 patients had successful laparoscopic resection with 77 patients (34.2%) requiring a laparoscopic-assisted approach, predominantly due to anatomic difficulties during the LS (50 out of 77 patients). Patients in the OP group were older [66 years old (OP) vs 59 years (LS), P < 0.001] and had slightly higher proportion of patients with ASA 3 and 4 [13.5% (OP) vs 10% (LS), P = 0.002]. The proportion of patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy was also higher among patients in the OP group compared to LS group [3.4% vs 2.5% (chemotherapy) and 2.9% vs 1.5% (radiotherapy) respectively]. The laparoscopic conversion rate was 11.1% (25 out of 225) with the reasons for conversion illustrated in Table 2. All conversions to OP were unplanned pre-operatively. Close to half (12 out of 25) of the patients were converted due to the presence of excessive adhesions. The oncologic and peri-operative outcomes of the entire study cohort are presented in Table 3. Duration of surgery was significantly longer in the LS compared to the OP group [162 min (LS) vs 119 min (OP), P < 0.001]. Length of hospitalization was shorter in the LS group compared to OP group (7 d vs 8 d, P < 0.001).

| Variables | Lap (%) n = 200 | Converted (%) n = 25 | Open (%) n = 408 | P value | |

| Gender | Male | 128 (64) | 15 (60) | 243 (60) | 0.570 |

| Female | 72 (36) | 10 (40) | 165 (40) | ||

| Median age (yr) | 59 | 63 | 66 | < 0.001 | |

| Ethnic group | Chinese | 172 (86) | 22 (88) | 352 (86.3) | 0.368 |

| Malay | 9 (4.5) | 0 | 19 (4.7) | ||

| Indian | 4 (2) | 2 (8) | 18 (4.4) | ||

| Others | 15 (7.5) | 1 (4) | 19 (4.7) | ||

| ASA | 1 | 75 (37.5) | 4 (16) | 84 (20.6) | 0.002 |

| 2 | 105 (52.5) | 20 (80) | 267 (65.4) | ||

| 3 | 20 (10) | 1 (4) | 55 (13.5) | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Location of tumor | Lower rectum | 68 (34) | 8 (32) | 131 (32.1) | 0.381 |

| Middle rectum | 90 (45) | 10 (40) | 212 (52) | ||

| Upper rectum | 42 (21) | 7 (28) | 65 (15.9) | ||

| Type of surgery | HAR | 30 (15) | 4 (16) | 24 (5.9) | 0.067 |

| LAR (w/stoma) | 27 (13.5) | 4 (16) | 82 (20.1) | ||

| LAR (w/o stoma) | 32 (16) | 5 (20) | 76 (18.6) | ||

| ULAR | 98 (49) | 12 (48) | 193 (47.3) | ||

| APR | 13 (6.5) | 0 | 33 (8.1) | ||

| Neo-adjuvant therapy status | Chemo-therapy | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 14 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Radio-therapy | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 12 (2.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Adjuvant therapy status | Chemo-therapy | 65 (32.5) | 15 (60) | 134 (32.8) | 0.071 |

| Radio-therapy | 28 (14) | 7 (28) | 82 (20.1) | 0.271 |

| Reason for conversion | No. of patients (% within converted patients) |

| Excessive adhesions | 12 (48) |

| Advanced tumor or excessive tumor fixation | 3 (12) |

| Difficult anatomy | 3 (12) |

| Intraoperative complications (e.g., bleeding, ureteric/urinary tract injury, bowel perforation/injury) | 4 (16) |

| Intolerant of tilt and pneumoperitoneum | 3 (12) |

| Variables | Lap (%) n = 200 | Converted (%) n = 25 | Open (%) n = 408 | P value | |

| Tumor grade | Well-differentiated | 20 (10) | 3 (12) | 38 (9.3) | 0.339 |

| Mod-differentiated | 173 (86.5) | 21 (84) | 349 (85.6) | ||

| Poorly-differentiated | 7 (3.5) | 1 (4) | 21 (5.1) | ||

| Median lesion size (cm) | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.275 | |

| T stage | T1 | 18 (9) | 3 (12) | 23 (5.6) | 0.151 |

| T2 | 43 (21.5) | 4 (16) | 73 (17.9) | ||

| T3 | 126 (63) | 9 (36) | 265 (65) | ||

| T4 | 13 (6.5) | 9 (36) | 47 (11.5) | ||

| Nodal status | N0 | 95 (47.5) | 10 (40) | 188 (46.1) | 0.77 |

| N+ | 105 (52.5) | 15 (60) | 320 (53.9) | ||

| TNM stage | Stage I | 47 (23.5) | 3 (12) | 69 (16.9) | 0.086 |

| Stage II | 51 (25.5) | 4 (16) | 111 (27.2) | ||

| Stage III | 75 (37.5) | 9 (36) | 162 (39.7) | ||

| Stage IV | 27 (13.5) | 9 (36) | 66 (16.2) | ||

| Perineural invasion | + | 38 (19) | 8 (32) | 90 (22.1) | 0.652 |

| - | 162 (81) | 17 (68) | 318 (77.9) | ||

| Vascular invasion | + | 61 (30.5) | 11 (44) | 135 (33.1) | 0.617 |

| - | 139 (69.5) | 14 (56) | 275 (66.9) | ||

| Median lymph nodes harvested (range) | 14 (4-90) | 15 (4-55) | 14 (3-56) | 0.447 | |

| Proximal margin (cm) | 9.9 (0-30) | 10 (2-22) | 12 (0-39) | 0.004 | |

| Distal margin (cm) | 2.1 (1-15) | 1.8 (1-15) | 2 (1-14) | 0.55 | |

| CRM < 2 mm | 29 (14.5) | 5 (20) | 75 (18.4) | 0.494 | |

| Median duration of surgery (min) | 162 | 147 | 119 | < 0.001 | |

| Length of hospitalization | 7 (3-159) | 7 (5-16) | 8 (3-78) | < 0.001 |

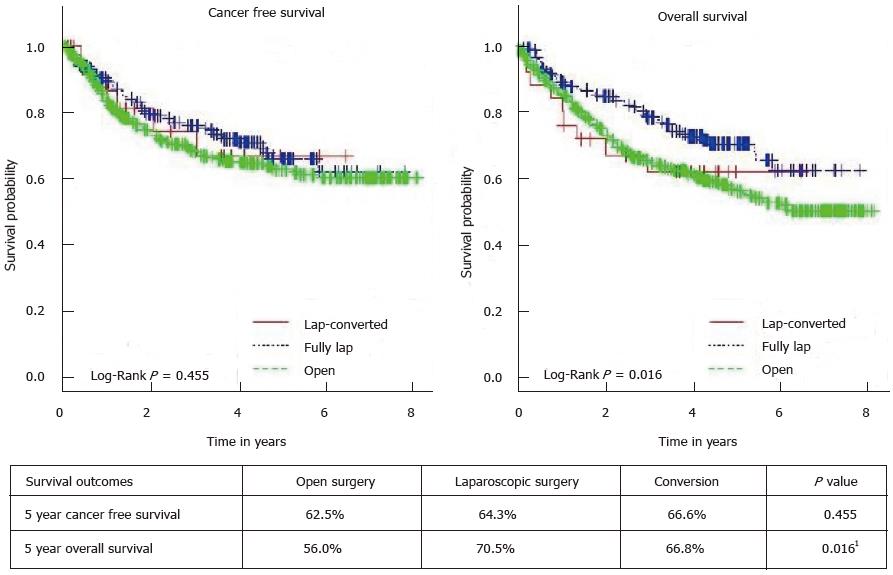

Comparison of short-term and long-term outcomes between the 3 groups is illustrated in Table 4 and there were no significant differences between the 3 groups. The 5-year CFS and OS for the 3 group of patients is illustrated in Figure 1. Results of the univariate and multivariate analyses for predictive factors of survival are summarized in Table 5. Factors found to be predictive of survival on univariate analysis include the laparoscopic approach (P = 0.016), together with factors such as age, ASA status, stage of disease, tumor grade, presence of perineural invasion and vascular emboli, CRM < 2 mm, and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. The survival benefit of LS was no longer significant on multivariate analysis (P = 0.148) and only age, stage of disease, tumor grade, and CRM < 2 mm remained significant. After excluding open cases, neither 5-year OS (70.5% vs 61.8%, P = 0.217) nor 5-year CFS (64.3% vs 66.6%, P = 0.854) were significantly different between the laparoscopic group and the converted group.

| Laparoscopic surgery n = 200 | Converted surgery n = 25 | Open surgery n = 408 | P value | |

| No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | ||

| Short-term outcomes | ||||

| Anastomotic leaks | 13 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 17 (4.2) | 0.233 |

| Wound complications | 8 (4) | 2 (8.0) | 31 (7.6) | 0.227 |

| Bleeding complications | 5 (2.5) | 1 (4.0) | 9 (2.2) | 0.840 |

| Ileus | 3 (1.5) | 2 (8.0) | 18 (4.4) | 0.097 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 8 (2) | 0.298 |

| Cardiac events | 7 (3.5) | 2 (8) | 17 (4.2) | 0.562 |

| 30 d mortality | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 8 (2.0) | 0.545 |

| Long-term | ||||

| Intestinal obstruction | 23 (11.5) | 5 (20) | 59 (14.5) | 0.396 |

| Incisional hernia | 9 (4.5) | 1 (4) | 33 (8.1) | 0.218 |

| Local recurrence | 9 (4.5) | 1 (4.0) | 36 (8.8) | 0.126 |

| Distant recurrence | 45 (22.5) | 6 (24) | 106 (26) | 0.644 |

| Variable | 5 yr overall survival (%) | Univariate P value | Overall survival HR (95%CI) | Multivariate P value |

| Age ≥ 65 vs < 65 | 50.9 vs 68.3 | < 0.0011 | 1.4557 (1.083-1.9568) | 0.0032 |

| Gender (male vs female) | 60.6 vs 60 | 0.921 | - | - |

| Lap vs converted vs open | 70.5 vs 61.8 vs 52.7 | 0.0161 | - | 0.148 |

| ASA 1/2 vs 3/4 | 62.6 vs 45.7 | 0.0161 | - | 0.131 |

| NeoadjChemo (yes vs no) | 59.5 vs 60.4 | 0.36 | - | - |

| NeoadjRT (yes vs no) | 66.7 vs 60.2 | 0.654 | - | - |

| AdjChemo (yes vs no) | 40.8 vs 70.5 | < 0.0011 | - | 0.06 |

| AdjRT (yes vs no) | 53.2 vs 62.3 | 0.206 | - | - |

| TNM stage (I-IV) | < 0.0011 | < 0.0012 | ||

| Stage I | 77.2 | Reference | ||

| Stage II | 73.8 | 1.04 (0.58-1.84) | 0.907 | |

| Stage III | 60.3 | 1.52 (0.89-2.58) | 0.124 | |

| Stage IV | 13.9 | 5.80 (3.26-10.33) | < 0.001 | |

| Tumor grade | 0.0021 | 0.0152 | ||

| Well differentiated | 75 | Reference | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 60.1 | 2.10 (1.00-4.40) | 0.049 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 39.1 | 1.18 (0.54-2.54) | 0.682 | |

| CRM < 2 mm vs > 2 mm | 40.1 vs 63.5 | < 0.0011 | 1.66 (1.19-2.32) | 0.0032 |

| No. of lymph nodes ≥ 12 vs < 12 | 62.2 vs 56.1 | 0.08 | - | - |

| Perineural invasion | 36.2 vs 67.3 | < 0.0011 | - | 0.276 |

| Vascular emboli | 46.2 vs 68.5 | < 0.0011 | - | 0.14 |

| Clinical symptoms of obstruction at presentation (yes vs no) | 35.3 vs 64.6 | < 0.0011 | 1.95 (1.39-2.74) | < 0.0012 |

In our study, the 5-year OS was 70.5% in the LS group vs 52.7% in the OP group. While the laparoscopic technique appeared to confer survival benefit on univariate analysis, this is likely attributed to the inherent selection bias in the study as patients chosen for OP tend to be older and with more advanced ASA status. As such, the differences in survival were no longer significant when subjected to multivariate analysis. There was also no difference in the local or systemic recurrence rates between all groups. These results are in line with several published studies comparing at least 5-year survival data of laparoscopic against open rectal resections (Table 6)[4,6,23-30]. They are also congruent with the findings of two recent randomized trials comparing laparoscopic with open resection in rectal cancer[31,32]. However, conflicting results were seen when pathologic adequacy of surgical resection was used as the outcome of interest. Both the ALaCaRT and the ACOSOG Z6051 trial failed to demonstrate non inferiority in terms of oncologic adequacy of resection when LS was compared to OP[33,34]. These results have cast doubt on the role of LS in rectal cancer. Hopefully, the long term follow up data of the above two studies will help shed light on the contentious issue of LS in rectal cancer.

| Ref. | Type of study | No. of patients with rectal cancer | 5 yr overall survival | Remarks |

| Lujan et al[4] | Randomized Controlled Trial | 204 (103 open, 101 lap) | 75.3% (open) vs 72.1% (lap) P = 0.980 | Middle and low rectal cancers only |

| Green et al[26], (MRC CLASICC trial) | Randomized Controlled Trial | 381 (128 open, 253 lap) | 52.9% (open) vs 60.3% (lap) P = 0.132 | |

| Ng et al[29] | Pooled Analysis of 3 RCT | 278 (142 open, 136 lap) | 61.1% (open) vs 63.0% (lap) P = 0.505 | 10 yr overall survival |

| Laurent et al[6] | Retrospective Comparative Study | 471 (233 open, 239 lap) | 79% (open) vs 82% (lap) P = 0.52 | Cancer free survival main outcome measure |

| Day et al[25] | Retrospective | 222 (133 open, 89 lap) | 58% (open) vs 75% (lap) P = 0.014 | Laparoscopic group had better survival on multivariate analysis as well |

| Baik et al[24] | Case-matched Controlled Analysis | 162 (108 open, 54 lap) | 88.5% (open) vs 90.8% (lap) P = 0.261 | |

| Li et al[28] | Retrospective | 238 (123 open, 113 lap) | 78.9% (open) vs 77.9% (lap) P = 0.913 | Middle and low rectal cancers only |

| Lim et al[21] | Retrospective | 191 (91 open, 100 lap) | 72.6% (open) vs 74.7% (lap) P = 0.54 | |

| Zhong et al[30] | Retrospective | 514 (238 open, 186 lap) | 61.3% (open) vs 69.4% (lap) P = 0.067 | |

| Agha et al[23] | Retrospective | 225 (all laparoscopic) | 50.5% (lap) | 10 yr overall survival |

Studies assessing the impact of conversion on oncological outcomes have shown conflicting results and a recent meta-analysis found that conversion was associated with an adverse long-term oncological outcome[35]. Postulated mechanisms include the increased inflammatory response associated with conversion and requirement for blood transfusion in converted cases that may subsequently increase recurrence risks[36]. However, both colonic and rectal resections were included in the above meta-analysis, with the former constituting the majority of the pooled patient population. Subset analysis of laparoscopic conversion in our study cohort revealed that conversion did not have an adverse impact on long-term oncologic outcomes in rectal cancer. Several studies have reported the impact of conversion in LRR for cancer[6,8,10,15,16,37]. While most studies had similar findings to ours, Rottoli et al[15] concluded that conversion could have a negative impact on long-term overall recurrence rate. It is noted in this study, however, that 8 out of 26 (30.7%) patients were converted due to advanced tumors and may thus explain poorer survival. In contrast, the majority of our conversions were due to adhesions (> 50%) and not advanced disease (12%) (Table 2). Thus it was not surprising that laparoscopic conversion had no impact on long-term oncologic outcomes.

The major limitation of our study lies in its retrospective nature which makes it susceptible to the effects of confounding and selection bias. While formal matching of the various groups of the study cohort was not performed due to numerical limitations, majority of the clinical demographics and tumor pathological characteristics between groups were similar, allowing for meaningful comparison. While we acknowledge the antecedent limitations of the retrospective nature of our study, it does have several strengths. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study cohort evaluating the long-term outcomes (5-year survival data) of surgical resection in rectal cancers. Unlike other studies, conversions were clearly defined which facilitates comparison of findings in other institutions. Thus, we believe that this study will add value to the available literature on surgical resection for rectal cancer.

LRR is safe and has equivalent long-term oncologic outcomes when compared to OP. Laparoscopic conversion does not appear to confer an adverse outcome. Further evaluation of long-term data from updated randomized studies comprising of larger number of patients may be required to discern more differences.

Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer remains controversial. The authors evaluate the long-term clinical and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic rectal resection and the impact of conversion in patients with rectal cancer.

The impact of laparoscopic conversion in rectal cancer remains unknown. This study assesses the impact of laparoscopic conversion in patients with rectal cancer.

Laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer has equivalent long term oncological outcomes when compared with open surgery. Conversion in rectal cancer was not shown to be associated with an adverse outcome.

Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer is feasible with no adverse impact on long term oncological outcomes even in the event of conversion.

LRR: Laparoscopic rectal resection; OP: Open surgery; LS: Laparoscopic surgery; CON: Converted laparoscopic surgery.

The paper describes a single-center experience on laparosocpic surgery for rectal cancer. It is well written and references are updated.

| 1. | Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Capretti G, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer patients: outcome and cost-benefit analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in RCA: 2328] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, Nam BH, Choi HS, Kim DW, Lim SB, Lee TG, Kim DY, Kim JS. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 687] [Cited by in RCA: 771] [Article Influence: 48.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:982-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou ZG, Hu M, Li Y, Lei WZ, Yu YY, Cheng Z, Li L, Shu Y, Wang TC. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1211-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Laurent C, Leblanc F, Wütrich P, Scheffler M, Rullier E. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: long-term oncologic results. Ann Surg. 2009;250:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vennix S, Pelzers L, Bouvy N, Beets GL, Pierie JP, Wiggers T, Breukink S. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD005200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Law WL, Lee YM, Choi HK, Seto CL, Ho JW. Laparoscopic and open anterior resection for upper and mid rectal cancer: an evaluation of outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1108-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lelong B, Bege T, Esterni B, Guiramand J, Turrini O, Moutardier V, Magnin V, Monges G, Pernoud N, Blache JL. Short-term outcome after laparoscopic or open restorative mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a comparative cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:176-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rickert A, Herrle F, Doyon F, Post S, Kienle P. Influence of conversion on the perioperative and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer compared with primarily open resection. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4675-4683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yamamoto S, Fukunaga M, Miyajima N, Okuda J, Konishi F, Watanabe M. Impact of conversion on surgical outcomes after laparoscopic operation for rectal carcinoma: a retrospective study of 1,073 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chan AC, Poon JT, Fan JK, Lo SH, Law WL. Impact of conversion on the long-term outcome in laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2625-2630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rottoli M, Stocchi L, Geisler DP, Kiran RP. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer: effects of conversion on long-term oncologic outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1971-1976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | White I, Greenberg R, Itah R, Inbar R, Schneebaum S, Avital S. Impact of conversion on short and long-term outcome in laparoscopic resection of curable colorectal cancer. JSLS. 2011;15:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rottoli M, Bona S, Rosati R, Elmore U, Bianchi PP, Spinelli A, Bartolucci C, Montorsi M. Laparoscopic rectal resection for cancer: effects of conversion on short-term outcome and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1279-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Agha A, Fürst A, Iesalnieks I, Fichtner-Feigl S, Ghali N, Krenz D, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Piso P, Schlitt HJ. Conversion rate in 300 laparoscopic rectal resections and its influence on morbidity and oncological outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:409-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kam MH, Seow-Choen F, Peng XH, Eu KW, Tang CL, Heah SM, Ooi BS. Minilaparotomy left iliac fossa skin crease incision vs. midline incision for left-sided colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chew MH, Ng KH, Fook-Chong MC, Eu KW. Redefining conversion in laparoscopic colectomy and its influence on outcomes: analysis of 418 cases from a single institution. World J Surg. 2011;35:178-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6617] [Article Influence: 413.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eu KW, Seow-Choen F, Ho JM, Ho YH, Leong AF. Local recurrence following rectal resection for cancer. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:393-396. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lim JW, Chew MH, Lim KH, Tang CL. Close distal margins do not increase rectal cancer recurrence after sphincter-saving surgery without neoadjuvant therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1285-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Seow-Choen F. Adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer cannot be based on the results of other surgeons. Br J Surg. 2002;89:946-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Agha A, Benseler V, Hornung M, Gerken M, Iesalnieks I, Fürst A, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Schlitt HJ. Long-term oncologic outcome after laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1119-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Baik SH, Gincherman M, Mutch MG, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW. Laparoscopic vs open resection for patients with rectal cancer: comparison of perioperative outcomes and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Day W, Lau PY, Li KM, Kwok SY, Yip AW. Clinical outcome of open and laparoscopic surgery in Dukes’ B and C rectal cancer: experience from a regional hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:26-32. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, Brown JM. Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 36.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kellokumpu IH, Kairaluoma MI, Nuorva KP, Kautiainen HJ, Jantunen IT. Short- and long-term outcome following laparoscopic versus open resection for carcinoma of the rectum in the multimodal setting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:854-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li S, Chi P, Lin H, Lu X, Huang Y. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery versus open resection for middle and lower rectal cancer: an NTCLES study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3175-3182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ng SS, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS, Mak TW, Leung WW, Leung KL. Long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2014;259:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Zhong B, Liu F, Yu J, Liang Y, Zhao L, Mou T, Hu Y, Li G. Comparison of long-term oncological outcomes of laparoscopic and open resection of rectal cancer. Nanfang Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2012;32:664-668. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, Choi HS, Kim DW, Chang HJ, Kim DY. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Lacy AM, Bemelman WA, Andersson J, Angenete E. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1324-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 87.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ, Davies L, Wilson K, Hague W, Simes J. Effect of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection vs Open Resection on Pathological Outcomes in Rectal Cancer: The ALaCaRT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1356-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 72.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M, Peters WR, Maun D, Chang G, Herline A. Effect of Laparoscopic-Assisted Resection vs Open Resection of Stage II or III Rectal Cancer on Pathologic Outcomes: The ACOSOG Z6051 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1346-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 755] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Clancy C, O’Leary DP, Burke JP, Redmond HP, Coffey JC, Kerin MJ, Myers E. A meta-analysis to determine the oncological implications of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:482-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ghinea R, Greenberg R, White I, Sacham-Shmueli E, Mahagna H, Avital S. Perioperative blood transfusion in cancer patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal resection: risk factors and impact on survival. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:549-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ströhlein MA, Grützner KU, Jauch KW, Heiss MM. Comparison of laparoscopic vs. open access surgery in patients with rectal cancer: a prospective analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Carboni F, Sinagra E S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL