Published online Apr 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i4.326

Peer-review started: October 1, 2015

First decision: November 13, 2015

Revised: November 22, 2015

Accepted: January 21, 2016

Article in press: January 22, 2016

Published online: April 27, 2016

Processing time: 202 Days and 20.8 Hours

AIM: To prospectively perform the PERFACT procedure in supralevator anal fistula/abscess.

METHODS: Magnetic resonance imaging was done preoperatively in all the patients. Proximal cauterization around the internal opening, emptying regularly of fistula tracts and curettage of tracts (PERFACT) was done in all patients with supralevator fistula or abscess. All types of anal fistula and/or abscess with supralevator extension, whether intersphincteric or transsphincteric, were included in the study. The internal opening along with the adjacent mucosa was electrocauterized. The resulting wound was left open to heal by secondary intention so as to heal (close) the internal opening by granulation tissue. The supralevator tract/abscess was drained and thoroughly curetted. It was regularly cleaned and kept empty in the postoperative period. The primary outcome parameter was complete fistula healing. The secondary outcome parameters were return to work and change in incontinence scores (Vaizey objective scoring system) assessed preoperatively and at 3 mo after surgery.

RESULTS: Seventeen patients were prospectively enrolled and followed for a median of 13 mo (range 5-21 mo). Mean age was 41.1 ± 13.4 years, M:F - 15:2. Fourteen (82.4%) had a recurrent fistula, 8 (47.1%) had an associated abscess, 14 (82.4%) had multiple tracts and 5 (29.4%) had horseshoe fistulae. Infralevator part of fistula was intersphincteric in 4 and transsphincteric in 13 patients. Two patients were excluded. Eleven out of fifteen (73.3%) were cured and 26.7% (4/15) had a recurrence. Two patients with recurrence were reoperated on with the same procedure and one was cured. Thus, the overall healing rate was 80% (12/15). All the patients could resume normal work within 48 h of surgery. There was no deterioration in incontinence scores (Vaizey objective scoring system). This is the largest series of supralevator fistula-in-ano (SLF) published to date.

CONCLUSION: PERFACT procedure is an effective single step sphincter saving procedure to treat SLF with minimal risk of incontinence.

Core tip: Supralevator fistula-in-ano (SLF) and abscess are quite difficult to treat. There is no good treatment available for this dreaded disease as the risk of incontinence is quite high when operating on such fistula. PERFACT (proximal cauterization around the internal opening, emptying regularly of fistula tracts and curettage of tracts) was done in seventeen patients with SLF. The overall healing rate was 80% (12/15). All patients could resume normal work within 48 h of surgery and there was no deterioration in incontinence scores. This is the largest series of treatment of SLF published to date.

- Citation: Garg P. PERFACT procedure to treat supralevator fistula-in-ano: A novel single stage sphincter sparing procedure. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(4): 326-334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i4/326.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i4.326

Supralevator abscess (SLA) constitutes up to 9% of all cryptoglandular abscesses[1-3]. These are difficult to treat as there is no satisfactory treatment procedure available which can manage these fistulas with a high success rate and minimal risk of incontinence. Conventionally adequate drainage followed by either a primary fistulotomy or a two stage fistulotomy using a seton fistula-in-ano was recommended[3]. There had been great enthusiasm for ligation of intersphincteric tract (LIFT) and even BioLIFT procedures, but recently the results have been disappointing[4].

Electrocauterization of the area around the internal opening can successfully close the internal opening of a fistula-in-ano[5]. This step along with curettage of the tracts and regularly emptying fistula tracts [proximal cauterization around the internal opening, emptying regularly of fistula tracts and curettage of tracts (PERFACT) procedure] has been shown to be effective in treating complex anal fistulas[5]. The efficacy of this procedure to manage supralevator fistula-in-ano (SLF) was assessed in this study.

This was a prospective analysis of all consecutive patients with cryptoglandular SLF and SLA treated from 2012 to 2014 at the referral colorectal unit of the hospital. The clearance (approval) was given by the institutional ethics committee. Informed consent was given by all the patients.

All types of anal fistula and/or abscess with supralevator extension, whether intersphincteric or transsphincteric, were included.

Patients who could not follow the postoperative schedule and protocol were excluded.

The Vaizey objective incontinence scoring was done preoperatively and at 3 mo after surgery[6]. On a scale of 0-24, a score of 0 implied perfect continence and a score of 24 meant total incontinence.

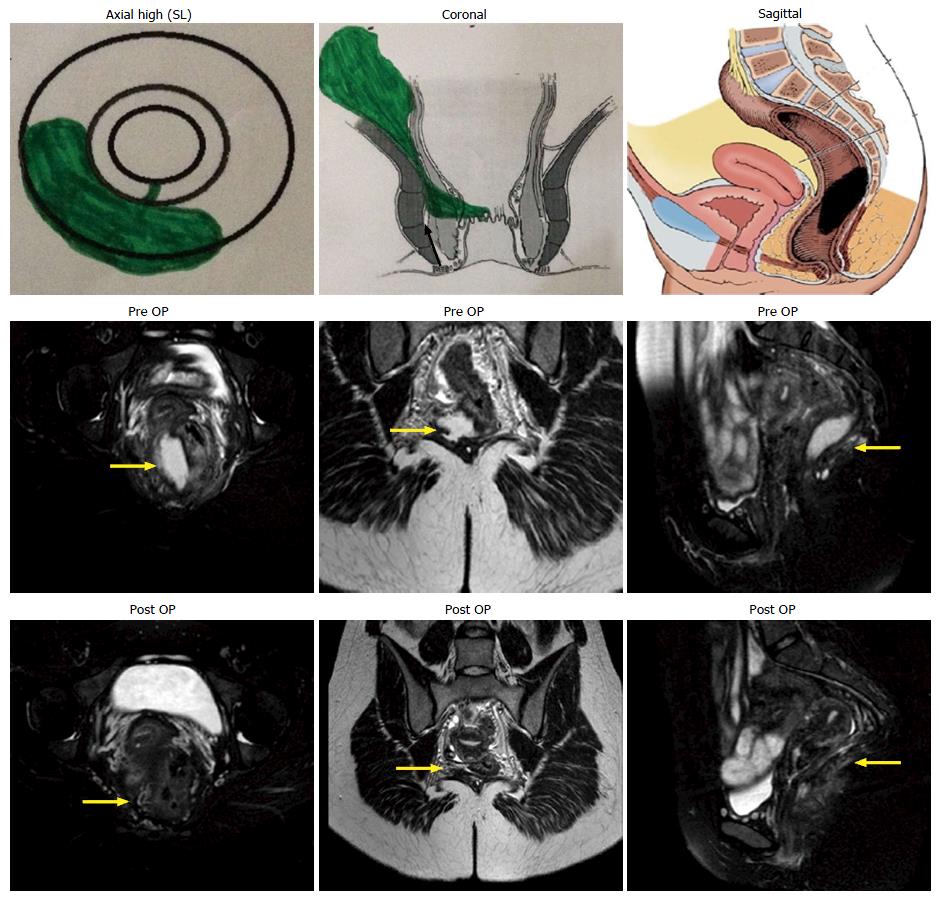

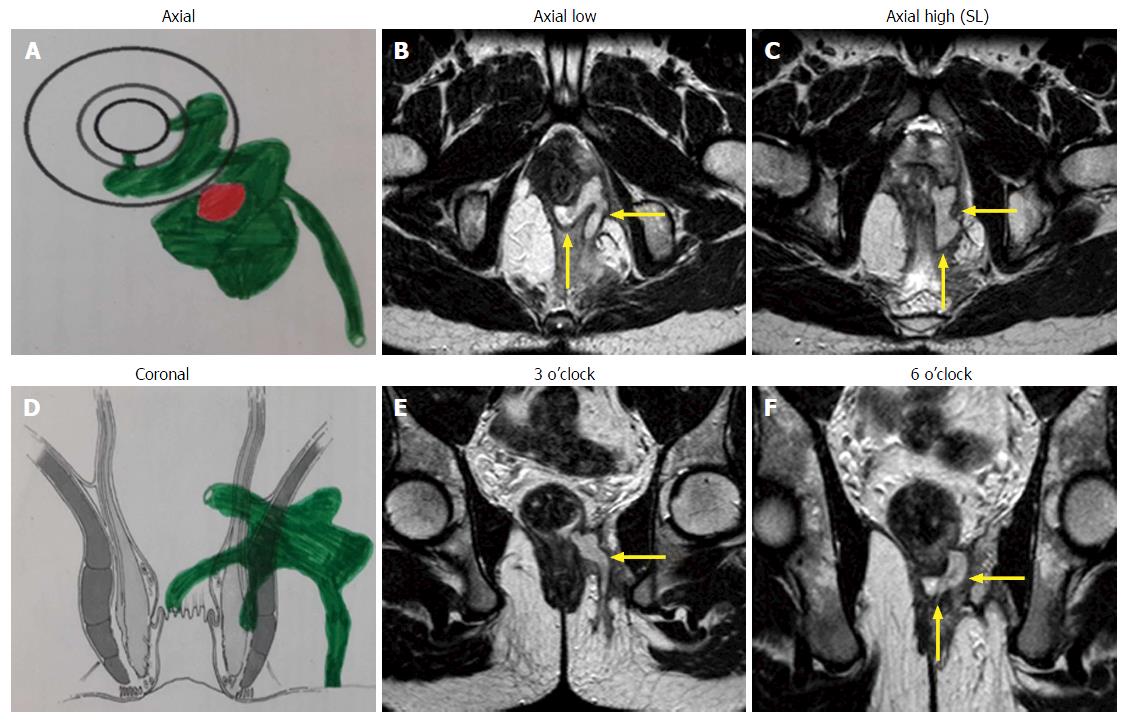

A preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was done in every case to accurately map the fistula tracts. A schematic diagram of the coronal and transverse sections was made based on the MRI (Figures 1-3).

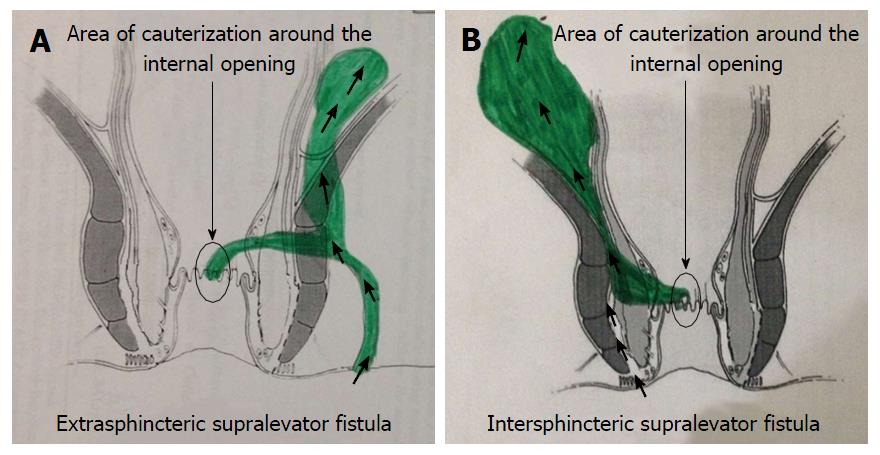

Intraoperatively, the procedure had two steps: (1) Electrocauterization around the internal opening: The superficial layer (mucosa) around the internal opening was electrocauterized to create a fresh wound (Figures 2 and 4). The resulting wound was encouraged to heal by secondary intention (granulation tissue). The aim was to permanently close (heal) the internal opening. If there was an additional supralevator opening in the rectum, the same procedure was done for that opening as well; and (2) curettage of tracts: All the tracts were thoroughly curetted and debrided of their lining with a curette. The transsphincteric supralevator tract/abscess was drained and curetted through the ischiorectal fossa through the external opening (Figure 2). The intersphincteric supralevator tract/abscess was curetted through the external opening already present or through a small new incision in the intersphincteric groove (Figure 2). Once the intersphincteric space was opened up, a blunt curette was introduced through the incision into this space. The curette was advanced towards the supralevator tract/collection, taking guidance from the MRI scan. A finger was kept in the rectum to prevent inadvertent injury to the rectal wall.

Regularly emptying fistula tracts: The curetted tracts were kept clean and empty of any serous fluid so as to ensure that the tracts healed (closed) by granulation tissue. Keeping all the tracts clean was required for 4 to 8 wk (occasionally longer) until all the tracts healed fully. The cleaning was usually done twice a day.

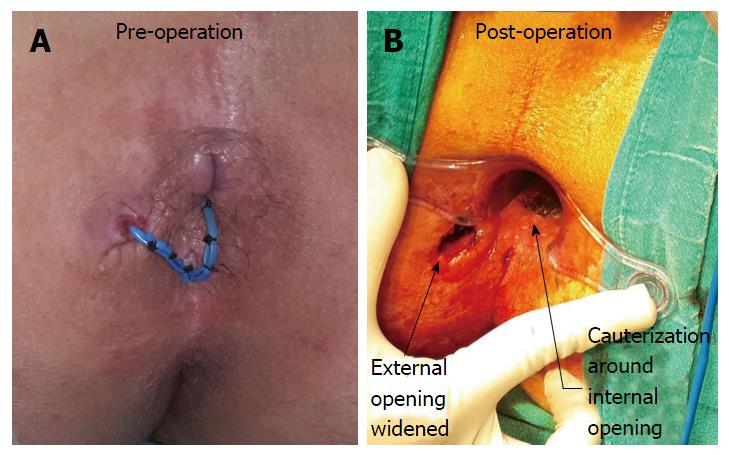

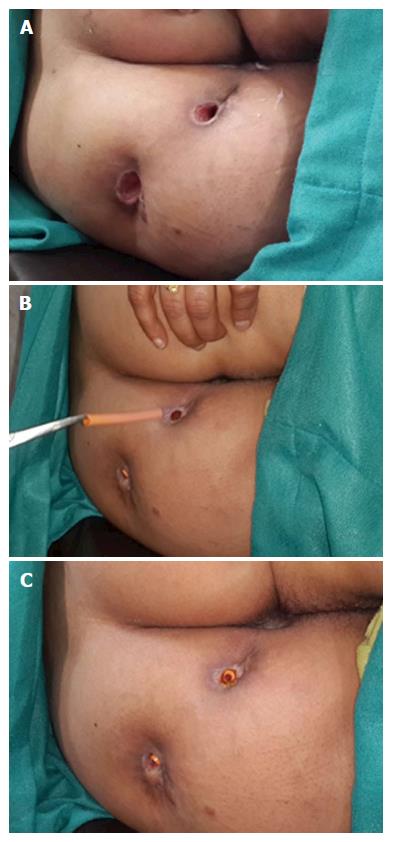

To ensure proper cleaning of the tracts, the following steps (one or multiple depending upon the requirement and fistula characteristics) were done during surgery: (1) The external opening was widened and the scarred puckered skin (if present) was excised. The aim was to make the external opening bigger than 1 cm x 1 cm (Figures 4 and 5). This facilitated cleaning of the tracts for a longer duration; (2) small tubes (red rubber, nasogastric or plastic) were put in the outer part of the tract to prevent premature closure of the outer part of the tract (Figure 5)[7]. The tube was removed before every dressing and then reinserted after the dressing. There was no need to secure the tube with a suture as the tract held the tube in place and the tube did not usually come out while walking. The cleaning was done with a swab mounted on artery forceps[7]. The schematic diagram (Figures 1-3) provided guidance regarding the direction and depth of the tracts. The tube size and diameter was gradually decreased as the deeper portion of the tracts healed. The insertion was stopped only after it was ensured that the deeper (including the supralevator) part of the tract had completely healed. The healing was assessed by narrowing of the tracts and non-negotiation of the swab in the upper part of the tract. Postoperative MRI was done in patients who could afford it to assess the healing (Figure 1); and (3) in cases of long multiple tracts or horseshoe tracts, multiple holes were made along the tract (Figure 5) so that all parts of the tract could be cleaned with ease.

A saddle block (spinal anesthesia) or general anesthesia was given. The patient was positioned in a lithotomy or prone jack-knife position. The internal opening was localized. This was facilitated by injecting saline or povidone iodine through the external opening.

Proximal superficial cauterization (Figures 2 and 4) was carried out with electrocautery around the internal opening, cauterizing only the mucosa and superficial part of the internal sphincter. The crypt glands, the internal opening and the tissue around it were cauterized. This usually resulted in an oval cauterized area, approximately 1 cm (wide) and 2 cm (long), with an internal opening at the center of the wound (Figures 2 and 4). After cauterization, the wound was left as such and no attempt was made to close the wound or the internal opening with any suture, stapler, glue or plug.

After this, the tracts were curetted in accordance with the MRI diagram and the tract lining was scrapped out as much as possible with a blunt curette (Figure 2). While doing so, a finger was kept in the rectum to ensure that the curette did not accidentally perforate the rectum.

The patient was discharged on the day of operation (if done under short general anesthesia) or the first postoperative day (if done under saddle or spinal anesthesia). Antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg and ornidazole 500 mg) were prescribed twice a day for five days. The patient was instructed to resume all his/her normal activities on the same day and was encouraged to walk briskly for five kilometers every day. This helped to keep the tracts empty.

The cleaning process of the curetted tracts was done by a cotton swab mounted on artery forceps[7]. The tube was removed before every dressing and then reinserted after the dressing (Figure 5). No povidone iodine, hydrogen peroxide or any liquid was injected in the tract during the cleaning process as this would have prevented the internal opening from closing. The cleaning was done by a trained nurse, a medical attendant or a relative. In our setting, teaching a relative was economical and easier and hence a preferred option.

The cleaning process was done two to four times a day. For the first 10 d, the patient was called to the outpatient clinic for supervised cleaning once or twice a day depending upon the complexity of the fistula. After this, the patient could do the cleaning process at home. The cleaning process was not painful, although uncomfortable at times. No sedation was required for this. The cure was defined as a complete cessation of a purulent or serous discharge and complete healing of all the tracts. Persistence of even one of the tracts was considered a failure.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Pankaj Garg, MBBS, MS, Chief Colorectal Surgeon at Garg Fistula Research Institute, Panchkula, India.

Seventeen patients were prospectively enrolled and followed for a median of 13 mo (3-21 mo). Mean age: 41.1 ± 13.4 years, M:F - 15:2. Fourteen (82.4%) had a recurrent fistula, 8 (47.1%) had an associated abscess, 14 (82.4%) had multiple tracts and 5 (29.4%) had horseshoe fistulae.

The infralevator part of fistula was intersphincteric in 4 (23.5%) (Figure 1) and transsphincteric in 13 (76.5%) patients (Figure 3, Table 1). All fistula were type 3 (suprasphincteric fistula) according to Park’s classification[8] and type 5 as per St James’ Hospital classification[9]. Two patients were excluded from the analysis (they could not follow the postoperative protocol). Out of 15 patients, 11 (73.3%) were cured (Figures 1 and 3) and four patients (26.7%) had a failure of treatment. All the patients with recurrence had transsphincteric supralevator extension (Table 1). Two patients with recurrence were reoperated on with the same procedure and one was cured. Thus, the overall healing rate was 80% (12/15). The tracts, especially the supralevator tract, did not heal in the failed treatment patients. All the patients were discharged within 24 h of the procedure and could resume normal work in 48 h There was no deterioration in incontinence scores at 3 mo after surgery.

| Case | Age (yr) | Sex | Previous operations | Site | Abscess | Horseshoe | Multiple tracts | Outcome |

| 1 | 62 | M | 2 | TS | N | N | N | Healed |

| 2 | 45 | M | 1 | TS | Y | Y | Y | Recurred, healed after reoperation |

| 3 | 45 | M | 1 | TS | N | N | Y | Healed |

| 4 | 49 | M | 2 | TS | N | N | Y | Not healed |

| 5 | 59 | M | 1 | TS | N | N | Y | Did not follow protocol/lost to follow-up |

| 6 | 48 | M | 1 | TS | Y | Y | Y | Healed |

| 7 | 36 | M | 2 | IS | Y | Y | Y | Healed |

| 8 | 26 | M | 0 | TS | Y | N | Y | Did not follow protocol/lost to follow-up |

| 9 | 22 | F | 3 | TS | Y | N | Y | Not healed, recurred after second operation |

| 10 | 32 | M | 1 | IS | N | Y | Y | Healed |

| 11 | 55 | M | 5 | IS | N | N | N | Healed |

| 12 | 25 | F | 0 | IS | Y | N | N | Healed |

| 13 | 59 | M | 1 | TS | N | N | Y | Healed |

| 14 | 22 | M | 1 | TS | Y | N | Y | Healed |

| 15 | 34 | M | 2 | TS | Y | N | Y | Healed |

| 16 | 34 | M | 1 | TS | N | N | Y | Not healed |

| 17 | 45 | M | 0 | TS | N | Y | Y | Healed |

| Total | 41.1 ± 13.4 | M-15/F-2 | Recurrent -14 | TS-13 | 8 | 5 | 14 | Healed-11 (73.3%) |

| IS-4 | Not-4 | |||||||

| Excluded-2 |

The study describes a novel simple method to treat supralevator fistula with a satisfactory cure rate (80%) and minimal risk to incontinence. The morbidity was also minimal as there was no cutting of sphincter muscle and the wound was quite small. Therefore, all the patients could resume their normal work within 48 h of surgery. As per our literature search, this is the largest series of supralevator fistula to be published.

MRI played a pivotal role in the diagnosis of supralevator extension. Endoanal ultrasound (EUS) and MRI are recommended for recurrent or suspected supralevator anal fistula[10-12]. Although both these modalities are quite sensitive in detecting perianal fistulas, the specificity of MRI is better than EUS[13]. Since ours is a referral center for anorectal fistulas, MRI is done in all our patients with perianal fistulas. The supralevator extension was an unsuspected incidental finding in 13 (76.5%) of our patients. Twelve (92.3%) of these 13 patients had recurrent anal fistula and 11 (84.6%) had multiple tracts. These findings reaffirm the suggestion that MRI should be done in all patients with recurrent and complex anal fistula[11-13]. MRI is perhaps the best method to assess SLA and fistula as it provides images in all three planes (axial, sagittal and coronal). The coronal view enables positioning of the abscess and the tract with respect to the levator plate and clearly shows supralevator extension in most patients (Figures 1 and 3)[14]. MRI is also a good modality to assess the resolution of the disease process. The photographs of preoperative and postoperative MRIs showing the resolution of the supralevator disease process are seen in Figure 1. The postoperative MRI of all the patients could not be done due to cost constraints.

Although the route of drainage of a SLA has been described in the past[2,3], there is no effective method available for definitive treatment of the SLF. The standard practice is to drain a SLA abscess through the rectum when a SLA spreads upwards from an intersphincteric abscess[15,16]. This is to avoid an iatrogenic suprasphincteric fistula if the drainage is incorrectly performed through the ischiorectal fossa. On the other hand, if a SLA is secondary to an upward extension of an ischiorectal abscess, the drainage should be performed through the ischiorectal fossa to avoid an iatrogenic extrasphincteric fistula[2,3,8,15,17,18]. Subsequent management is opening the intersphincteric space through the rectum by dividing the internal anal sphincter (IAS) or by a staged seton procedure.

Both the internal and external anal sphincters play an important role in maintaining continence[19-21]. Using cutting seton in high transsphincteric anal fistula can affect continence in up to 60% of patients[19]. On the other hand, completely sparing the external anal sphincter (EAS) but dividing the IAS to open the intersphincteric space through the rectum in intersphincteric fistulas also leads to continence deficits in up to 50% of patients[20]. Therefore, both IAS and EAS play a significant role in continence preservation[20,21]. A recent multicenter study reported a long term incidence of major incontinence (Vaizey score > 6) in 26.8% of patients undergoing fistulotomy in low perianal fistulas[22]. This further emphasizes the need to move towards sphincter saving procedures to treat anal fistula.

The PERFACT procedure is perhaps the first method described to treat supralevator fistula which does not involve dividing either the internal or external anal sphincter. Therefore, the continence scores did not show any deterioration in any patient postoperatively. Secondly, unlike the conventional methods[15], this procedure aimed to cure SLA and fistula in a single step. This made it less morbid and quite cost effective as it prevented the cost of a second admission and reoperation.

The concept behind this procedure was very simple. It aimed to close the internal opening by proximal superficial cauterization in the anal canal (Figures 2 and 4). In the postoperative period, it was ensured that the wound healed by secondary intention so that the internal opening was sealed by granulation tissue. The closure of an internal opening by natural means (granulation tissue) seems to be a good alternative to other methods of closures by primary intention, such as a plug, suture, flap, stapler or a clip[23-25].

In the PERFACT procedure, the internal opening is not widened. If the internal opening is widened, there is a chance of stool passing through the internal opening. In this procedure, only the mucosa (superficial layer) all around the internal opening is electrocauterized so as to create a fresh raw wound which heals with granulation tissue. The internal and external sphincters are not cut. Due to this, the internal opening is not wider than it was before surgery.

The second step was curettage of the tracts. This ensured that the infected epithelium was removed and the freshened raw wound in the tracts led to the generation of the granulation tissue which facilitated the closure of the tracts. However, the serous discharge of the granulation tissue needed to be thoroughly cleaned/removed from the tracts on regular basis as otherwise the stagnant discharge would become infected, leading to a collection. The latter would not only lead to the rapid reepithelialization of the tracts, but also the collected fluid could flow into the internal opening, thereby preventing its closure.

At times, the tracts were curved and branching. Preoperative MRI, which was done in all cases, helped to accurately localize the tracts. Once this was done, it helped to curette the tracts (primary tract as well as the branching secondary tracts). For this purpose, curettes of different sizes and lengths were kept handy. Cleaning the curved tracts usually did not pose much problem as the tracts were usually flexible and adapted to the shape of the curette.

The postoperative management was quite significant. It aimed to keep the tracts clean and empty and any inadequacy in this care was detrimental to the final outcome.

The cauterization of the internal opening alone was tried earlier without much success[5]. The reason for the success of the same step in the PERFACT procedure needs explanation. Undoubtedly, the internal opening is the prime culprit in a fistula-in-ano as it allows ingress of the bacteria from the anal canal into the fistula tracts. However, once the tracts are formed and are lined by the infected epithelium, it is a mutually propagating situation. The patent internal opening keeps the tracts infected and the infected collection in the tracts keeps the internal opening patent. Therefore, isolated attempts to close the internal opening would fail until it is accompanied by meticulous cleaning, emptying and healing of all the associated tracts. This perhaps explains the need for regular tract cleaning in the postoperative period.

The PERFACT procedure can also be done effectively in fistula cases where the internal opening cannot be localized accurately during surgery. The possible reasons of failure to identify the internal opening are twofold. Firstly, it could be due to the temporary closure of the internal opening due to debris. Secondly, it could be the closure of the collapsible fistula tract (which passes through the sphincter complex) due to the external pressure of the sphincter muscle. As per the published literature, this can happen in up to 15%-20% of cases. In the earlier published series of the PERFACT procedure, an internal opening could not be found in 15.7% (8/44) of cases[5]. Still, this procedure was successful in 87.5% (7/8) of these patients[5]. The MRI was done preoperatively in every case. This helped to localize the position of the tracts in the majority of cases and gave a reasonable idea where the tract is coursing towards the rectum. This information along with the examination findings during surgery (induration of the sphincter in the region of internal opening) helped to determine the most likely location of the internal opening. The superficial cauterization was done at that place. This was a safe step to do as it created only a superficial wound with no injury/damage to either of the sphincters.

The concept behind this procedure was undoubtedly simple but to achieve good results in complex anal fistulas, it required detailed analysis of the MRI scan, careful planning and mapping of the tracts (preoperatively), meticulous curettage and cleaning of all the tracts (intraoperatively) and disciplined postoperative care (postoperatively).

As discussed, the main benefit of this procedure was its ability to treat SLA/fistula in a single sitting with minimal risk to incontinence. The morbidity was also minimal as no extensive tissue cutting was done. Apart from a small superficial wound in the anal canal, the external opening was slightly widened (Figures 4 and 5). The cauterized anal wound was also small (usually about 2 cm long and 1 cm wide) (Figure 4). Due to these small wounds, the patients had little pain and were able to resume all their normal daily activities from the first postoperative day. The patients were encouraged to briskly walk 4-5 km from the first postoperative day as it facilitated keeping the tracts empty. Secondly, as both the sphincters were completely spared, the negative impact on incontinence was minimal.

The tube (mushroom catheter) has been used for drainage of perianal abscesses, both ischiorectal abscesses[26] and supralevator abscesses[15]. However, a tube has perhaps not been used in the way described in this study (to keep the outer part of the fistula tract patent). In the present procedure, a tube in the outer portion of the fistula helped in several ways (Figure 5). First, it prevented the outer portion of the fistula tract from closing prematurely[7]. The tube was placed until the upper inner portion of the fistula did not heal completely. Premature closure of the outer part of the tract, especially the skin, would risk accumulation of fluid which could prevent healing of the upper part[7]. Second, unlike a loose draining seton, nothing (no seton or thread) needs to be passed through the internal opening in this technique[7]. This helped to achieve the closure of the internal opening which would not have been possible if a draining seton had been used instead. Third, to drain supralevator extension (with no rectal opening), a draining seton could not be used whereas a tube could be used for adequate regular drainage.

The results in fistulae with intersphincteric infralevator part (100% - 4/4) (Figure 1) were better than fistulae with transsphincteric infralevator part (72.7% - 8/11) (Figure 3). The reason for this could be that the intersphincteric space was a collapsible space. Once the abscess was adequately drained (or the fistula tract adequately curetted) and the internal opening healed by cauterization, the intersphincteric space had the tendency to collapse (close) (Figure 1).

It was observed in this series that the supralevator component usually developed some time after the development of an infralevator anal fistula. If the infralevator anal fistula was intersphincteric, then it extended upwards in the intersphincteric plane (Figure 2). Even if the infralevator anal fistula was transsphincteric, the supralevator extension was in the intersphincteric plane (Figure 2). Thus, the supralevator extension was always in the intersphincteric plane. Since the supralevator rectal opening was not present in all fistula-in-ano patients with supralevator extension, it indicated that the supralevator rectal opening developed later and was not as important in the pathophysiology of SLF. Mucosal papilla (granulation tissue overgrowth) was also observed at the site of the supralevator rectal opening in four patients. Such overgrowth of granulation tissue usually occurs at the point of exudation of purulent discharge. These points indicated that the supralevator rectal opening developed as a result of bursting the supralevator intersphincteric abscess/collection into the rectum and this opening mainly acted as a point of drainage for the abscess/fistula. The primary source of ingress of bacteria was perhaps the opening at the dentate line. Another point in favor of this concept is that the intramural pressure during defecation in the anal canal (hence at dentate line) is quite high, whereas the intramural pressure in the rectum is comparatively low as it is a storage organ. This high pressure in the anal canal “forces” bacteria into the opening at the dentate line and this may be responsible for the persistence and propagation of the fistula and, in a few cases, development of a SLA. A small proportion of these cases then progresses to also develop a supralevator rectal opening. Further data is needed to substantiate these observations. Unfortunately, too little data is available on supralevator anal fistula due to rarity of this disease and the difficulty in management it poses.

Other advantages of this procedure were the less operating time (20-30 min), the procedure was easy to perform and reproduce and no expensive gadgets were required, such as in VAAFT or an anal fistula plug[23,25,27].

The PERFACT procedure is quite different from VAAFT. In VAAFT, the internal opening is closed by a stapler or suturing whereas in PERFACT, the mucosa (superficial layer) all around the internal opening is electrocauterized so as to create a fresh raw wound which heals with granulation tissue. The aim is to close the internal opening by secondary intention whereas in VAAFT, the aim is to close the internal opening by primary intention. Closure of tissues by primary intention put tissues under tension which increases the risk of failure. That could perhaps be the reason that the PERFACT procedure seems to be more effective than VAAFT, especially in complex and supralevator fistulas.

This was a prospective cohort study with no control group. Undoubtedly, a control group would have added value to the study. However, a comparative study was not feasible as the prevalence of supralevator fistula is quite low. Secondly, no other procedure in the literature has been shown to be effective in supralevator fistula, especially in supralevator fistula with transsphincteric component. Therefore, a comparative study could not be planned.

To conclude, the PERFACT procedure is an effective single step sphincter saving procedure to treat supralevator anal fistula. It is associated with little morbidity and minimal risk to incontinence. Long term studies with large numbers of patients are required to substantiate the results.

Supralevator fistula-in-ano (SLF) and abscess are quite difficult to treat. There is no good treatment available for this dreaded disease to date. The reason is that the risk of incontinence is quite high in operating on such fistula.

SLF is extremely difficult to treat. Conventionally, drainage of the abscess is followed by either a primary fistulotomy or a two-stage fistulotomy using a seton, but these were associated with high incontinence rates. There has been great enthusiasm for ligation of intersphincteric tract and even Bio ligation of intersphincteric trac procedures, but the results have been disappointing.

This is the largest study of treatment of SLF to be published. Proximal cauterization around the internal opening, emptying regularly of fistula tracts and curettage of tracts (PERFACT) is a minimally invasive treatment in which the risk of sphincter damage is very low. This procedure was done in seventeen patients with SLF. The overall healing rate was 80% (12/15). All the patients could resume normal work within 48 h of surgery and there was no deterioration in incontinence scores.

The PERFACT procedure is a simple novel procedure with many distinct advantages. As there is no satisfactory treatment available for supralevator fistula, this procedure provides a ray of hope to treat this dreaded disease.

This is a very nice study on the PERFACT procedure. The PERFACT procedure allows treating supralevator fistula without dividing either the internal or external anal sphincter. Therefore, the continence scores showed no deterioration in any of the patients postoperatively and this procedure aimed to cure supralevator abscess and fistula in a single step.

| 1. | Read DR, Abcarian H. A prospective survey of 474 patients with anorectal abscess. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:566-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ramanujam PS, Prasad ML, Abcarian H, Tan AB. Perianal abscesses and fistulas. A study of 1023 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:593-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Prasad ML, Read DR, Abcarian H. Supralevator abscess: diagnosis and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:456-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wallin UG, Mellgren AF, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM. Does ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract raise the bar in fistula surgery? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1173-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garg P, Garg M. PERFACT procedure: a new concept to treat highly complex anal fistula. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4020-4029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 963] [Cited by in RCA: 1011] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Garg P. Tube in tract technique: a simple alternative to a loose draining seton in the management of complex fistula-in-ano: video vignette. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 961] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS. MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics. 2000;20:623-635; discussion 635-637. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, Fürst A, Sailer M, Schiedeck T. German S3 guideline: anal abscess. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Steele SR, Kumar R, Feingold DL, Rafferty JL, Buie WD. Practice parameters for the management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1465-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL, van der Hoop AG, Kessels AG, Vliegen RF, Baeten CG, van Engelshoven JM. Preoperative MR imaging of anal fistulas: Does it really help the surgeon? Radiology. 2001;218:75-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Siddiqui MR, Ashrafian H, Tozer P, Daulatzai N, Burling D, Hart A, Athanasiou T, Phillips RK. A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of endoanal ultrasound and MRI for perianal fistula assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:576-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Halligan S, Stoker J. Imaging of fistula in ano. Radiology. 2006;239:18-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Garcia-Granero A, Granero-Castro P, Frasson M, Flor-Lorente B, Carreño O, Espí A, Puchades I, Garcia-Granero E. Management of cryptoglandular supralevator abscesses in the magnetic resonance imaging era: a case series. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1557-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | García-Granero A, Granero-Castro P, Frasson M, Flor-Lorente B, Carreño O, Garcia-Granero E. The use of an endostapler in the treatment of supralevator abscess of intersphincteric origin. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O335-O338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hanley PH. Reflections on anorectal abscess fistula: 1984. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:528-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rickard MJ. Anal abscesses and fistulas. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:64-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Isbister WH, Al Sanea N. The cutting seton: an experience at King Faisal Specialist Hospital. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lunniss PJ, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Factors affecting continence after surgery for anal fistula. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1382-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Thomson JP, Ross AH. Can the external anal sphincter be preserved in the treatment of trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano? Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Göttgens KW, Janssen PT, Heemskerk J, van Dielen FM, Konsten JL, Lettinga T, Hoofwijk AG, Belgers HJ, Stassen LP, Breukink SO. Long-term outcome of low perianal fistulas treated by fistulotomy: a multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schwandner O. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) combined with advancement flap repair in Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Prosst RL, Joos AK, Ehni W, Bussen D, Herold A. Prospective pilot study of anorectal fistula closure with the OTSC Proctology. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Garg P, Song J, Bhatia A, Kalia H, Menon GR. The efficacy of anal fistula plug in fistula-in-ano: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:965-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Beck DE, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Catheter drainage of ischiorectal abscesses. South Med J. 1988;81:444-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Garg P. To determine the efficacy of anal fistula plug in the treatment of high fistula-in-ano: an initial experience. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Attaallah W, Brusciano L, Lara FJP, Milone M, Santoro GA S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Li D