Published online Feb 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i2.169

Peer-review started: April 30, 2015

First decision: June 24, 2015

Revised: October 8, 2015

Accepted: November 3, 2015

Article in press: November 4, 2015

Published online: February 27, 2016

Processing time: 311 Days and 21.7 Hours

A 26-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of abdominal distention and vomiting. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a blind loop of the bowel extending to near the uterus and a fibrotic band connecting the mesentery to the top of the bowel, suggestive of Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) and a mesodiverticular band (MDB). After intestinal decompression, elective laparoscopic surgery was carried out. Using three 5-mm ports, MD was dissected from the surrounding adhesion and MDB was divided intracorporeally. And subsequent Meckel’s diverticulectomy was performed. The presence of heterotopic gastric mucosa was confirmed histologically. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged 5 d after the operation. She has remained healthy and symptom-free during 4 years of follow-up. This was considered to be an unusual case of preoperatively diagnosed and laparoscopically treated small-bowel obstruction due to MD in a young adult woman.

Core tip: Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is a rare innate anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract caused by incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct. It sometimes causes small bowel obstruction. However, as it symptoms are so non-specific, it may be difficult to make a correct diagnosis without exploratory laparotomy. This is a successful case of small-bowel obstruction caused by MD that was diagnosed preoperatively using multi-dimensional contrast-enhanced computed tomography and treated by elective laparoscopic surgery.

- Citation: Matsumoto T, Nagai M, Koike D, Nomura Y, Tanaka N. Laparoscopic surgery for small-bowel obstruction caused by Meckel’s diverticulum. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(2): 169-172

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i2/169.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i2.169

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is one of the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract that results from an incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct[1,2]. It has an incidence of 1%-2% among the general population, and most cases remain asymptomatic[2]. The rate of developing complicated MD is reported to be about 4% throughout lifetime[3], which comprises bleeding, inflammation or obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction may occur in cases where there is a volvulus or an internal hernia around a diverticulum, intussusception, or incarceration of the diverticulum in an inguinal (Littré) hernia[1]. However, as its symptoms, such as abdominal pain, distention, vomiting or constipation, are so non-specific, it may be difficult to make a correct diagnosis, and exploratory laparotomy is often required.

Here we report a case of small-bowel obstruction caused by MD that was diagnosed preoperatively using multi-dimensional contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and treated by elective laparoscopic surgery.

A 26-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital complaining of abdominal pain and recurrent vomiting. She had been hospitalized because of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome 2 years previously, and had also suffered an episode of small-bowel obstruction 1 year prior to admission, which had been diagnosed as food impaction. She had no episode of hematochezia.

Physical examination demonstrated abdominal distention, with a soft abdomen and no tenderness or rebound pain. Her bowel sounds were hyperactive. Results of a hematologic examination were normal, and a urine pregnancy test gave a negative result.

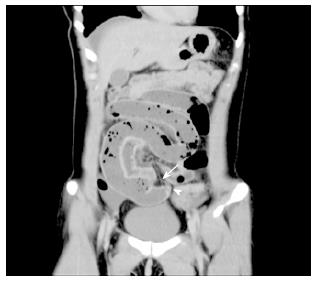

Abdominal plain X-ray examination demonstrated a ladder-like series of distended small-bowel loops (Figure 1). Multi-dimensional CECT showed a blind-ending U-shaped loop of bowel in the pelvis and a fibrotic band connecting the mesentery to the blind end of the bowel, suggesting MD and a mesodiverticular band (MDB) (Figure 2). A change in the caliber of the ileum was evident adjacent to the band.

We diagnosed the patient as having small-bowel obstruction, probably caused by adhesion to the MDB of MD, without any sign of vascular compromise.

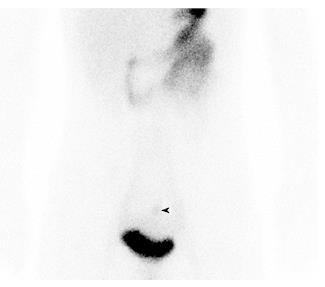

A long tube was placed and her small intestine was successfully decompressed. After the tube had been removed, scintigraphy with 99mTc-Na-pertechnetate was performed, and this revealed uptake in the lower abdomen (Figure 3).

Although surgical treatment was proposed, the patient expressed a wish to temporarily leave hospital because of pressing business matters. She was therefore discharged after 1 wk of hospitalization.

Two months after discharge, we performed elective laparoscopic surgery using three 5-mm ports. MD was dissected from the surrounding adhesion and MDB was divided intracorporeally. Then subsequent Meckel’s diverticulectomy was performed extracorporeally via a 2 cm mini-laparotomy. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 5, and she has since remained healthy and symptom-free during 4 years of follow-up.

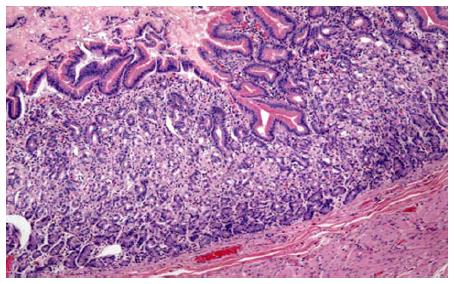

Histological examination confirmed the presence of a MDB (Figure 3) and heterotopic gastric mucosa in the mucosa of the diverticulum (Figures 4 and 5).

MD is an innate anomaly of the gastrointestinal system caused by incomplete closure of the omphalomesenteric duct[1]. MD was so named in 1809 after its discoverer, the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Meckel. The presence of MD can be explained in terms of intrauterine evolution of the bowel. The omphalomesenteric duct is the embryonic communication between the yolk sac and the developing midgut. By the 10th week of embryogenesis, the omphalomesenteric duct becomes a thin fibrous band. However, incomplete atrophy of the omphalomesenteric duct may result in a variety of anomalies, they are, umbilicoileal fistula, omphalomesenteric duct cyst or MD[4].

The diverticulum originates from the antimesenteric border of the small bowel, within 40-100 cm of the ileocecal valve[4,5]. Blood is supplied via the vitelline artery, which is a branch of the ileocecal artery. The diverticulum is ordinarily lined by intestinal mucosa, but the heterotopic gastric mucosa or pancreatic tissue was frequently observed by the histological examination[4,5].

Reportedly, 25% of MD become symptomatic throughout the lifetime[4]. Bleeding, inflammation or obstruction are the main cause of complication[2]. Statistically, hemorrhage is the most common presentation in children aged 2 years or younger[6], whereas intestinal obstruction is the commonest presentation among adults[7]. Intestinal obstruction due to MD is the most common presentation in adults and the second most common in children[6,7].

The clinical symptoms are non-specific; patients may have abdominal pain and distension, vomiting or constipation. MD-related small-bowel obstruction occurs so infrequently that most articles have reported only small series or isolated cases. Moreover, many patients with MD have non-specific abdominal symptoms, often making a correct preoperative diagnosis difficult, especially in an emergency setting[8,9].

The present case illustrates that abdominal CECT has the potential to identify the MDB and MD as the cause of small-bowel obstruction. Multi-dimensional CECT, especially in the coronal view, may yield more information about the cause of the small-bowel obstruction and the presence of a MDB. CECT is less invasive and speedier than other examinations such as Tc scintigraphy, interventional radiology or a gastrointestinal series, and therefore is more preferable in an emergency setting, yielding information about the cause of the small-bowel obstruction, such as internal hernia or other intestinal mass. CECT can also reveal the presence of strangulation. In the present case, we were able to confirm by CECT that there was no sign of vascular compromise, enabling us to start intestinal decompression in preparation for elective laparoscopic surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery for MD has been widely used recently. However, as it is not clear whether laparoscopic surgery is preferable to laparotomy in the setting of small-bowel obstruction[10], we performed intestinal decompression first. MD can be resected either extracorporeally or intracorporeally[9,11]. Although some reports have indicated intracorporeral laparoscopic diverticulectomy, we selected laparoscopy-assisted diverticulectomy via a small incision in the lower abdomen to allow palpation of the MD, thus helping to rule out any mass or thickening of the base, and allowing a more complete assessment for the presence of any ectopic gastric mucosa[12].

In conclusion, we successfully treated MD causing small bowel obstruction by laparoscopic surgery. Multi-dimensional CECT may yield to detect both the etiology of small-bowel obstruction and the presence of strangulation in such unusual settings.

A 26-year-old woman with past history of small bowel obstruction presented with abdominal pain and recurrent vomiting.

Physical examination demonstrated abdominal distention, with a soft abdomen and no tenderness or rebound pain. Her bowel sounds were hyperactive.

Small bowel obstruction due to food impaction, sue to internal hernia, or due to intestinal tumor.

All labs were within normal limits.

Multi-dimensional contrast enhanced computed tomography showed a blind-ending U-shaped loop of bowel in the pelvis and a fibrotic band connecting the mesentery to the blind end of the bowel, suggesting Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) and a mesodiverticular band (MDB).

MDB and heterotopic gastric mucosa in the mucosa of the MD.

Long tube decompression and subsequent laparoscopic diverticulectomy.

MD occurs with an incidence of 1%-2% among the general population, and most cases remain asymptomatic. Complications result most commonly from bleeding, inflammation, or obstruction.

The MDB is an embryologic remnant of the vitelline circulation which carries the arterial supply to the Meckel’s diverticulum. In the event of an error of involution, a patent or nonpatent arterial band persists and extends from the mesentery to the apex of the anti-mesenteric diverticulum.

This is a successful case of small-bowel obstruction caused by MD that was diagnosed preoperatively using multi-dimensional contrast-enhanced computed tomography and treated by elective laparoscopic surgery.

This is an interesting report on a rare etiologic factor of bowel obstruction in young adults.

| 1. | Platon A, Gervaz P, Becker CD, Morel P, Poletti PA. Computed tomography of complicated Meckel’s diverticulum in adults: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:53-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Park JJ, Wolff BG, Tollefson MK, Walsh EE, Larson DR. Meckel diverticulum: the Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950-2002). Ann Surg. 2005;241:529-533. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dumper J, Mackenzie S, Mitchell P, Sutherland F, Quan ML, Mew D. Complications of Meckel’s diverticula in adults. Can J Surg. 2006;49:353-357. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Levy AD, Hobbs CM. From the archives of the AFIP. Meckel diverticulum: radiologic features with pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:565-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Rossi P, Gourtsoyiannis N, Bezzi M, Raptopoulos V, Massa R, Capanna G, Pedicini V, Coe M. Meckel’s diverticulum: imaging diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:567-573. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rutherford RB, Akers DR. Meckel’s diverticulum: a review of 148 pediatric patients, with special reference to the pattern of bleeding and to mesodiverticular vascular bands. Surgery. 1966;59:618-626. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Alvite Canosa M, Couselo Villanueva JM, Iglesias Porto E, González López R, Montoto Santomé P, Arija Val F. [Intestinal obstruction due to axial torsion and gangrene of a giant Meckel diverticulum]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;35:452-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sharma RK, Jain VK. Emergency surgery for Meckel’s diverticulum. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sai Prasad TR, Chui CH, Singaporewalla FR, Ong CP, Low Y, Yap TL, Jacobsen AS. Meckel’s diverticular complications in children: is laparoscopy the order of the day? Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sauerland S, Agresta F, Bergamaschi R, Borzellino G, Budzynski A, Champault G, Fingerhut A, Isla A, Johansson M, Lundorff P. Laparoscopy for abdominal emergencies: evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:14-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Saggar VR, Krishna A. Laparoscopy in suspected Meckels diverticulum: negative nuclear scan notwithstanding. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:747-748. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Cobellis G, Cruccetti A, Mastroianni L, Amici G, Martino A. One-trocar transumbilical laparoscopic-assisted management of Meckel’s diverticulum in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Gheita TA, Ciaccio EJ, Lakatos PL, Vegh Z S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL