Published online Dec 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i12.766

Peer-review started: May 17, 2016

First decision: July 11, 2016

Revised: August 10, 2016

Accepted: October 1, 2016

Article in press: October 9, 2016

Published online: December 27, 2016

Processing time: 219 Days and 0.8 Hours

Select group of patients with concurrent esophageal and gastric stricturing secondary to corrosive intake requires colonic or free jejunal transfer. These technically demanding reconstructions are associated with significant complications and have up to 18% ischemic conduit necrosis. Following corrosive intake, up to 30% of such patients have stricturing at the pyloro-duodenal canal area only and rest of the stomach is available for rather less complex and better perfused gastrointestinal reconstruction. Here we describe an alternative technique where we utilize stomach following distal gastric resection along with Roux-en-Y reconstruction instead of colonic or jejunal interposition. This neo-conduit is potentially superior in terms of perfusion, lower risk of gastro-esophageal anastomotic leakage and technical ease as opposed to colonic and jejunal counterparts. We have utilized the said technique in three patients with acceptable postoperative outcome. In addition this technique offers a feasible reconstruction plan in patients where colon is not available for reconstruction due to concomitant pathology. Utility of this technique may also merit consideration for gastroesophageal junction tumors.

Core tip: Selected patients with concurrent esophageal and gastric stricturing secondary to corrosive intake require colonic or free jejunal transfer. These technically demanding reconstructions are associated with significant conduit necrosis. An alternative technique we utilize stomach with Roux-en-Y reconstruction instead of colonic or jejunal interposition has been presented.

- Citation: Waseem T, Azim A, Ashraf MH, Azim KM. Roux-en-Y augmented gastric advancement: An alternative technique for concurrent esophageal and pyloric stenosis secondary to corrosive intake. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(12): 766-769

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i12/766.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i12.766

Corrosive upper gastrointestinal (GI) strictures still remain challenging in surgical practice[1]. Fortunately in majority of cases these either preferentially involve esophagus or stomach making surgical decision easier in favor of either esophagectomy or a form of gastric bypass[1,2]. However in approximately 6%-50% of the cases it involves both esophagus and stomach making reconstruction a technically demanding task with inherent potential of multiple complications[1-3].

Various surgical techniques with pros and cons have been advocated previously[4-6]. Colonic and free jejunal conduits remain a standard for such difficult cases with favorable outcomes however with significant graft necrosis rates of 2.4%-18% and 14.1% respectively[6-8]. Although proponents of colonic conduit have significant reasons in favor of its use however majority of the surgeons doing transhiatal resections of esophagus would agree that stomach is the most favorable conduit in terms of quality of blood supply and hence anastomotic leak rate[9]. In a study by Mansour et al[10], bowel interposition was associated with significant complications including 14.8% anastomosis leakage rate and 3% ischemic colitis rate. Similarly, Davis et al[6] and Moorehead et al[11] have previously shown that stomach is better in terms of postoperative ischemia than the colon. Stomach had lowest conduit ischemia rate of 0.5%-1% while jejunum had colon had ischemia up to 11.3% and 13.3% respectively[6-11]. Patients having colonic interposition however, have low rates of GERD postoperatively[12,13].

In a group of selected patients where the stomach has mere concentric pyloric stenosis along with esophageal involvement, many practicing surgeons would have questioned themselves per-operatively: “Can we employ this dilated well vascularized stomach instead of less vascular and technically more demanding colon or free jejunal transfer?” Here we describe alternative reconstruction plan which we have successfully employed in three of our patients with reasonable outcome.

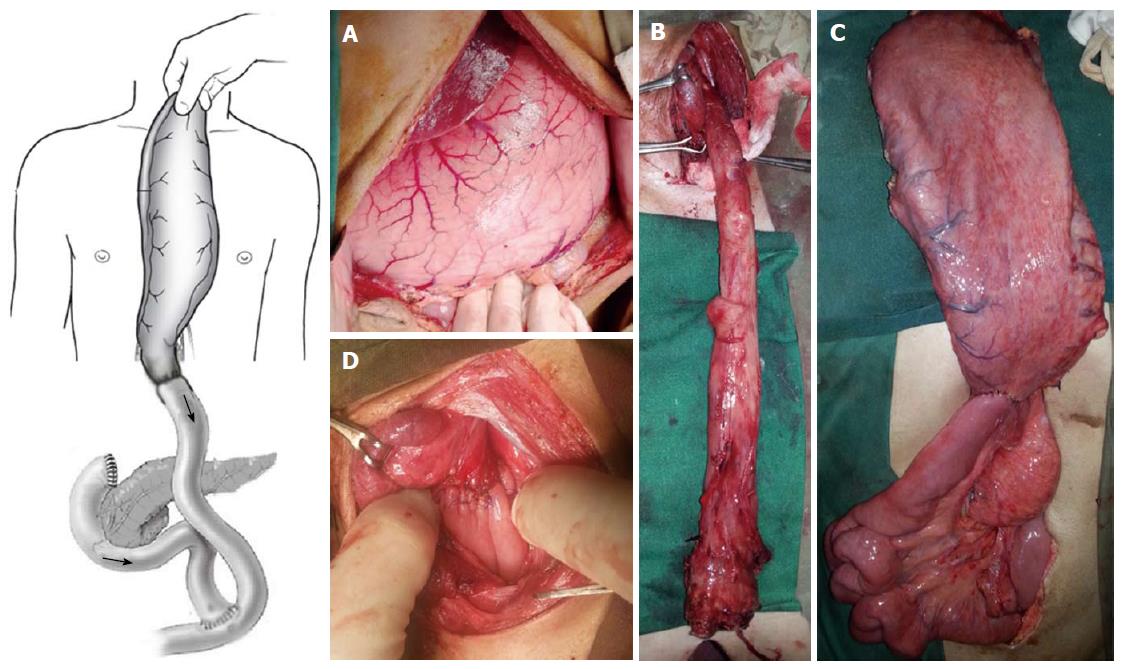

A 33-year-old male patient presented with development of progressive dysphagia following history of caustic intake 3 years back. Endoscopy showed two significant strictures in upper GI tract, one 30 cm distal to cricopharyngeus and the second one in pyloric sphincter region. During last three years patient was managed by repeated dilatations of esophageal and pyloric strictures. Now he presented with strictures which were not dilatable due to extensive fibrosis in the said areas of the upper GI tract. A barium study showed esophageal stricture in the region of upper esophagus and the stomach was full of the contrast material without any distal evacuation (Figure 1). Another dilatation of the upper esophageal stricture was possible in up to 5 mm at best. Considering the above surgical reconstruction was planned. Peroperatively the stomach was massively dilated with only distal stricturing at the pyloric region. Stomach was mobilized with preservation of right gastroepiploic vessels. Distal gastrectomy was done and distal end of stomach was closed along with closure of the duodenal stump. Transhiatal esophagectomy was done and jejunum was fashioned as a Roux-en-Y loop which was anastomosed to the distal end of the mobilized stomach. The stomach was delivered into the chest the way that the gastro-jejunal anastomosis of Roux-en-Y loop lays in hiatus. Neck dissection was done with predictable safety of recurrent laryngeal nerve. End to side triangulated gastroesophageal anastomosis was done with interrupted Prolene stitches (Figure 2). Postoperatively patient did well and was discharged on 18th postoperative day. We have employed the same technique in three of our patients, tow males and one female. All three patients had technically viable reconstruction. We lost one of the three patients on 12nd postoperative day due to Acinobacter positive hospital acquired pneumonia. We did not find any evidence to suggest a procedural failure or anastomotic leakage in this particular case. We have followed up the cases over a period of 19 mo in one case and 5 mo in other case with only one with mild dumping symptoms.

Corrosive intake depending upon the chemical composition of ingested liquid, area and time of contact can cause mild to severe stricturing of the upper GI tract[1-3]. Caustic soda preferentially affects the esophagus and the toilet cleaners in majority of cases affect the pyloric canal area[3]. Endoscopic dilatation or surgical replacement is quite effective treatment in majority of the cases[3]. In up to 50% percent of the cases there is concurrent involvement of esophagus and stomach leading to difficulty in reconstruction. In such cases, colonic interposition and free jejunal transfer still remain the gold standard conduits. Clearly such reconstructions are complex and are associated with higher morbidity and mortality[4]. In words of T. DeMeester, these reconstructions should be flawless because the impact of complications is not additive but logarithmic[14]. In experienced hands these reconstructions have favorable results however one of the frequently encountered problem is higher conduit necrosis rate in case of colon (2.8%-18%) and jejunum (14.1%) as opposed to stomach which has lower conduit necrosis rate (2.6%) and hence potentially lower leak rate[6-8].

In select group of the patients with concurrent involvement of esophagus and stomach where stomach is merely affected at the pyloric sphincter area, surgeons have previously avoided using stomach in favor of colonic replacement. Here we have demonstrated that stomach tube along with Roux-en-Y reconstruction can be a feasible alternative to the colonic or jejunal interposition in this select group of patients.

The interposition of stomach tube potentially adds specific superiority of excellent vascular supply and potentially reduced conduit necrosis rate and low anastomotic leakage rate, which are subject of our upcoming randomized trial. The Roux-en-Y reconstruction adds to the complexity of the reconstruction however it has three distinct advantages: Firstly, it gives significant length to the conduit (about 30-40 cm), which normally would be attained by liberal kockerization of the duodenum in a standard case of the transhiatal esophagectomy; secondly, it would function as a pyloromyotomy which is frequently done by the surgeons during transhiatal esophagectomy to prevent postoperative gastric stasis and thirdly, it potentially would reduce postoperative biliary reflux; and finally, this reconstruction plan can be of enormous value if the colon is not available for interposition due to some other concomitant reason like ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Theoretically such reconstruction can also be beneficial in GE junction tumors, where we can achieve negative resection margins with limited resection of stomach.

RAGA like other constructions plans can be associated with potential complications. The preparation of the conduit requires special attention and preservation of blood supply as the conduit would be solely based on right gastroepiploic artery and its corresponding venous system as opposed to right gastroepiploic and right gastric arteries which are usually preserved during a standard transhiatal esophagectomy. This can potentially add to the probability of gastric erosions due to mucosal ischemia. Secondly the retention gastritis leading to postoperative gastric erosions are likely to be higher and hence patients may require use of proton pump inhibitors to prevent gastric erosions due to gastritis. One of our patient developed postoperative gastric erosions on 6th postoperative day owing to retention gastritis which was successfully treated with proton pump inhibitor infusion. A predicted comparison of the two said techniques has been tabulated in Table 1.

| Colonic interposition | Roux-en-Y augmented gastric advancement | |

| Vascular supply and conduit necrosis rates | Good; conduit necrosis rate 2.4%-18% | Potentially excellent; conduit necrosis rate 2%-5% |

| Mild mucosal ischemia | Ischemic colitis (3%) | Gastric erosions |

| Gastroesophageal and colo-esophageal reflux rates | Low (4%-5%) | Low |

| Conduit reservoir capacity | Acceptable | Better |

| Postprandial conduit fullness | Less | More |

| Probability of cervical esophageal anastomotic leakage rate | Low | Low |

| Probability of postoperative esophageal anastomotic stricture formation | Low | Higher |

| Potential complications | Higher probability of anastomotic leakage in colonic anastomosis | Higher probability of gastric erosions postoperatively due to retention gastritis |

In select group of the patients of corrosive intake with concomitant involvement of esophagus and stomach where stomach is partially available for reconstruction, it is feasible to utilize stomach for reconstruction in place of more complex colonic or jejunal transfer with favorable results. A randomized trial is warranted to compare this alternative reconstruction plan with gold standard colonic and jejunal transfer.

| 1. | Chaudhary A, Puri AS, Dhar P, Reddy P, Sachdev A, Lahoti D, Kumar N, Broor SL. Elective surgery for corrosive-induced gastric injury. World J Surg. 1996;20:703-706; discussion 706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tohda G, Sugawa C, Gayer C, Chino A, McGuire TW, Lucas CE. Clinical evaluation and management of caustic injury in the upper gastrointestinal tract in 95 adult patients in an urban medical center. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1119-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Keh SM, Onyekwelu N, McManus K, McGuigan J. Corrosive injury to upper gastrointestinal tract: Still a major surgical dilemma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5223-5228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | DeMeester TR, Johansson KE, Franze I, Eypasch E, Lu CT, McGill JE, Zaninotto G. Indications, surgical technique, and long-term functional results of colon interposition or bypass. Ann Surg. 1988;208:460-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Foker JE, Ring WS, Varco RL. Technique of jejunal interposition for esophageal replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;83:928-933. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Davis PA, Law S, Wong J. Colonic interposition after esophagectomy for cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dickinson KJ, Blackmon SH. Management of Conduit Necrosis Following Esophagectomy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2015;25:461-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wormuth JK, Heitmiller RF. Esophageal conduit necrosis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006;16:11-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Orringer MB, Marshall B, Chang AC, Lee J, Pickens A, Lau CL. Two thousand transhiatal esophagectomies: changing trends, lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2007;246:363-372; discussion 372-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mansour KA, Bryan FC, Carlson GW. Bowel interposition for esophageal replacement: twenty-five-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:752-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moorehead RJ, Wong J. Gangrene in esophageal substitutes after resection and bypass procedures for carcinoma of the esophagus. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990;37:364-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yildirim S, Köksal H, Celayir F, Erdem L, Oner M, Baykan A. Colonic interposition vs. gastric pull-up after total esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:675-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Briel JW, Tamhankar AP, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Johansson J, Choustoulakis E, Peters JH, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Prevalence and risk factors for ischemia, leak, and stricture of esophageal anastomosis: gastric pull-up versus colon interposition. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:536-541; discussion 541-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Markar SR, Arya S, Karthikesalingam A, Hanna GB. Technical factors that affect anastomotic integrity following esophagectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4274-4281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kimura A, Kozarek RA, Ladd AP S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D