Published online Oct 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.679

Peer-review started: May 16, 2016

First decision: June 14, 2016

Revised: August 13, 2016

Accepted: August 30, 2016

Article in press: August 31, 2016

Published online: October 27, 2016

Processing time: 164 Days and 11.4 Hours

To highlight the rising trend in hospital presentation of foreign bodies retained in the rectum over a 5-year period.

Retrospective review of the cases of retained rectal foreign bodies between 2008 and 2012 was performed. Patients’ clinical data and yearly case presentation with data relating to hospital episodes were collected. Data analysis was by SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, United States.

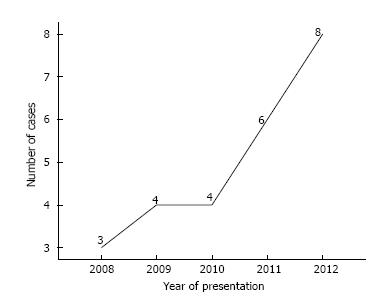

Twenty-five patients presented over a 5-year period with a mean age of 39 (17-62) years and M: F ratio of 2:1. A progressive rise in cases was noted from 2008 to 2012 with 3, 4, 4, 6, 8 recorded patients per year respectively. The majority of the impacted rectal objects were used for self-/partner-eroticism. The commonest retained foreign bodies were sex vibrators and dildos. Ninty-six percent of the patients required extraction while one passed spontaneously. Two and three patients had retrieval in the Emergency Department and on the ward respectively while 19 patients needed examination under anaesthesia for extraction. The mean hospital stay was 19 (2-38) h. Associated psychosocial issues included depression, deliberate self-harm, illicit drug abuse, anxiety and alcoholism. There were no psychosocial problems identified in 15 patients.

There is a progressive rise in hospital presentation of impacted rectal foreign bodies with increasing use of different objects for sexual arousal.

Core tip: There is a progressive rising incidence of retained rectal foreign bodies with increasing use of different designed and improvised objects for sexual arousal. The clinicians in the emergency settings must be well informed about the approach to the care of the patients with foreign bodies retained in the rectum.

- Citation: Ayantunde AA, Unluer Z. Increasing trend in retained rectal foreign bodies. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(10): 679-684

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i10/679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i10.679

Hospital presentation with foreign bodies retained in the rectum is no longer rare although concrete epidemiological data are still lacking[1,2]. The earliest report of rectal foreign body dates back to the sixteenth century[3]. There have been recent reports to suggest an increasing incidence and hospital presentations with foreign bodies retained within the rectum[1-6]. Our prediction is that it is very much likely that such increasing hospital presentations shall continue to rise with the use of different objects for anal sexual fantasy. Objects retained in the rectum are mainly encountered in the adults following either intentional or non-intentional insertion. Occasionally, the retained objects may result from accidental or deliberate ingestion which had travelled through the whole of the gastrointestinal tract only to be impacted in the rectum[1-3,6,7].

These patients usually present to the Emergency Department (ED) due to anorectal, pelvic or lower abdominal pain[1,4]. Typically, the patients have delayed hospital presentation after several failed attempts at retrieving the object[1-7]. The delayed presentation, particularly due to the perceived shame and/or associated embarrassment, presents both diagnostic and management challenges to the emergency staff[1,2]. The fact that significant numbers of these patients are often reluctant to volunteer the truth about the circumstances surrounding their presentation in the ED further contributes to the diagnostic delay. Therefore, the care of the patients with foreign bodies retained within the rectum requires a methodical approach for diagnosis, retrieval of the foreign body and post-extraction clinical observation[1,2]. The desired ultimate outcome for every case is a safe and successful per anum extraction of foreign body, in a manner as to respecting the patients’ right to dignity, privacy and confidentiality.

We present our experience with retained rectal foreign bodies to highlight a rising trend in presentation over a 5-year period and the approach to management.

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of all retained rectal foreign bodies that were managed in our hospital over a 5-year period, 2008 to 2012. Patients coded on the hospital Patient Administrative System (PAS) with a diagnosis of rectal foreign bodies were identified. Patient and clinical related data were collected from the hospital records right from the ED presentation through to the admission episode until discharge. Data collected relate to patients’ demography, clinical presentation, types of the objects, circumstance relating to insertion, the time from insertion to presentation, physical examination findings, investigations and treatment offered. The yearly case presentation, types of retained rectal foreign bodies, length of hospital stay, associated complications and psychosocial problems were recorded.

A total of 25 patients presented to our ED and treated for retained rectal foreign bodies over the 5 years study period. The mean age was 39 (17-62; SD 13.98) years with 17 males and 8 females giving a gender ratio of 2 to 1. We noted a progressive rise in the number of cases that presented per year from 2008 to 2012 with 3 recorded cases in 2008 and rising to the highest level of 8 cases in 2012 (Figure 1). Various objects impacted in the rectum and the reasons for insertion are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. The presenting complaint were anorectal pain (4), failure to self -retrieve the object (14), persistent vibration and anorectal pain (2), anorectal pain and failure to retrieve the object (3) and anorectal pain and rectal bleeding (2). The mean period between rectal object insertion and the visit to the ED was 14 (1-72; SD 14.6) h. Fifty-two percent (13/25) of the patients volunteered having had previous anorectal insertion of the same object ranging from 2 to 5 episodes with no problem.

| Retained rectal objects | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Apple fruit | 1 | 4 |

| Glass jar | 2 | 8 |

| Nail vanish bottle | 1 | 4 |

| Sex toy (dildo) | 5 | 20 |

| Sex vibrator | 12 | 48 |

| Denture (accidentally ingested and retained in the rectum) | 1 | 4 |

| Roll on deodorant bottle | 2 | 8 |

| Ceramic candle holder | 1 | 4 |

| Reasons for insertion of retained rectal foreign body | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Self erotism | 9 | 36 |

| Partner erotism | 13 | 52 |

| Self-massage of rectal prolapse | 1 | 4 |

| Self-harm | 1 | 4 |

| Accidental ingestion of denture | 1 | 4 |

Physical examination findings were completely normal in 11 while elicited clinical findings were tender lower abdomen in 3, palpable rectal foreign bodies on digital rectal examination (DRE) in 10 and blood in the rectum with palpable object in 1. Plain abdominal and pelvic X-ray were performed in all patients and erect chest X-ray was selectively performed only in 4 cases where indicated to exclude any free peritoneal gas under the diaphragm. Plain X-ray film confirmed the presence of retains rectal foreign objects in all cases but in one patient with apple in the rectum where it was not so obvious on the plain film. There was no specific indication for computerised tomography (CT) scan in any of these patients and therefore this investigation was not done.

Extraction of the retained rectal objects was required in 24 of the 25 patients. One patient passed the object spontaneously while waiting to be taken to the operating theatre. Two patients whose retained foreign bodies were easily palpable had the objects retrieved in the ED by digital manipulation and discharged. Three patients underwent digital removal of the retained rectal foreign bodies on the surgical assessment ward and were kept for a period of observation. Nineteen patients needed examination under anaesthesia (EUA) and extraction of retained foreign bodies in the operating theatre. Of the 19 patients, 15 had the objects extracted with grasping forceps with the aid of a proctoscope and/or a rigid sigmoidoscope, 2 were retrieved using small Keilland’s forceps, 1 was digitally removed and one patient with impacted apple in the rectum was broken down and removed piecemeal. Rigid sigmoidoscopy was performed in 19 of 25 patients post extraction to exclude anorectal injury with the status of the anal sphincters assessed and recorded in each case. Two patients sustained anorectal mucosal tear, one of which developed significant bleeding per rectum post extraction; in one patient the sex toy had broken in ano; otherwise there was no complication recorded in 22 patients. There was no evidence of perforation identified in any of our patients in this series either during the EUA and/or following the period careful in hospital clinical observation.

The mean length of hospital stay was 19 (2-38; SD 9.56) h. All our patients had successful per anum extraction of the object with no one requiring a laparotomy or laparoscopy. Identified psychosocial issues in some of the patients included depression and deliberate self-harm in 3, illicit drug abuse in 2, anxiety in 2, depression in 1 and excess alcohol consumption in 2. There were no psychosocial problems identified in 15 patients. There was no correlation between the presence of psychosocial issues and either repeat insertion or number of previous insertions of rectal foreign bodies.

Rectal insertion of objects and retention are commonly seen in the adults. These are either used in the majority of cases for anal sexual stimulation or sometime for criminal intent[1-9]. Occasionally, retained rectal foreign body may have resulted from self-treatment of anorectal conditions, attempts at concealment of illicit drugs or weapons and accidental ingestion of objects which eventually get impacted in the anorectum as in one of our patients[1,2,4,8,10-13]. There is a wide range of objects finding their ways into the rectum and we and other authors have previously predicted a possible rise in the incidence and presentations in the ED following the of various objects for erotic fantasy[1-4,6,8].

The current study shows a progressive increase in the number of cases that presented over a 5-year period from 2008 through to 2012 from a single centre. This outlook confirmed what we and some other authors have predicted previously[1-4,6,8]. This most recent study has demonstrated a significant rise in the number of cases per year compared with studies by Safioleas et al[5] who reported 34 patients over a 25-year period, Coskun et al[6] with a report of 15 patients over a 10-year study period (1999-2009), Rodríguez-Hermosa et al[7] with 30 patients over an 8-year period (1997-2004) and our previous report of 16 cases over a 4-year period (2001-2004)[8]. We can only expect a continuing rise in the hospital presentations of impacted foreign bodies within the rectum given the increasing fantasy with a wide variety of improvised household and designed objects. Table 3 summarises the trend in the published literature over the last few decades. The sudden surge in the incidence reported by Lake et al[4] covering a 10 year study period was a data from a very large United States population and stands as the largest published data on this subject in the literature. The current data and our previous report[8] have shown a rising trend in the ED cases of objects impacted in the rectum.

| Ref. | Study years | No of cases | Average cases per year | M:F ratio |

| Huag et al[14] | 1979-2000 (21 yr) | 10 | 0.48 | 10:00 |

| Lake et al[4] | 1993-2002 (10 yr) | 87 | 8.7 | 17:01 |

| Clarke et al[13] | 1995-2005 (10 yr) | 13 | 1.3 | 13:00 |

| Rodríguez-Hermosa et al[7] | 1997-2004 (8 yr) | 30 | 3.75 | 15:01 |

| Ayantunde et al[8] | 2001-2004 (4 yr) | 16 | 4 | 15:01 |

| Safioleas et al[5] | 1971-2006 (25 yr) | 34 | 1.36 | 6:1 |

| Coskun et al[6] | 1999-2009 (10 yr) | 15 | 1.5 | 15:00 |

| Ayantunde et al | 2008-2012 (5 yr) | 25 | 5 | 2:1 |

This study also affirmed the persistent male preponderance as it was variously reported in the published literature although there seems to be a slightly higher female population in the current study than previously reported[1-10]. The gender ratio showed that the male population was only twice affected as female gender in the current study. This reduced male to female ratio may have been due to a significant increase in the group of female gender using objects for partner-erotism in this cohort than previously reported. The majority of our patients were young adults who were using the retained objects for either self-erotism or partner-erotism. Eighty eight percent of our patient population were using the foreign bodies for erotic stimulation and this is in agreement with the previous published reports[1-4,7-10]. The changing pattern with increasing female gender and predominantly younger population than previously reported may likely be the emerging trend in the presentations of retained rectal foreign bodies.

Our previous work[8] and that of Cohen and Sackier[9] have shown objects used for sexual interaction accounted for more than three-quarter of the cases of impacted foreign bodies in the rectum presenting to hospitals. One patients in this study inserted an apple fruit for self-harm. This patient disclosed that he was abused as a child and became very depressed after the loss of his wife. One patient was using the object for self-massage of rectal mucosal prolapse in an attempt to reduce it while one accidentally swallowed their dentures, which later became impacted in the rectum prompting the presentation to the ED. We did not encounter any patient in the current series with retained rectal foreign bodies with history of sexual rape or other violent sexual practices as previously reported by some authors[1,2,8,14,15].

Generally speaking, patients with rectal foreign bodies do not attend the ED early unless attempts have been made to retrieve the objects by the patient or their partners because of the perceived embarrassment and shame[1-4,7,8,12-14]. The majority of our patients attended the ED because of failure to retrieve the foreign bodies after several attempts while few others presented with anorectal pain and/or bleeding. Two of our patients in particular presented because of persistent vibration of the powered sex toys causing them significant anorectal and lower abdominal pain. The delay in presentation may be due to the hope of a spontaneous passage of the foreign objects by the patient and the eventual failure to pass against their expectation leads to some measure of anxiety[1].

The initial evaluation at presentation should include a careful history, abdominal and digital rectal examinations (DRE) including the assessment of the status of the perianal region and anal sphincters with the findings clearly documented before and after the extraction of the foreign body in the clinical notes[1-4,8,14-16]. Confirmation of the type, size, number and location of the objects should be by biplanar plain abdominal and pelvic films[1-3,8,14]. Biplannar plain X-rays in this study showed the foreign objects in all but one of our patients. The one patient with retained apple fruit was not so obvious on the plain films. Erect chest X-ray and CT scan should only be selectively performed where indicated. Plain erect chest radiograph is recommended to exclude the presence of free peritoneal gas under the diaphragm indicating rectosigmoid perforation[1]. There was no patient in this series with any specific indication requiring a CT scan evaluation. CT scan where indicated is excellent for localization of non-opaque foreign bodies, detection of perforation or obstruction and diagnosis of pelvic abscess[1].

The basic approach to the management of patients with retained foreign bodies include achieving a safe per anum extraction, direct visualisation of the rectosigmoid mucosal to exclude bowel injury and a period of close clinical observation in the hospital for early detection of complications[1-4,8,16]. Extraction of impacted rectal foreign bodies should be achieved under direct vision where possible using an anoscope or sigmoidoscope to avoid iatrogenic anorectal injury[1-4,8,14,16].

Generally speaking, the determination of level of the retained foreign bodies in the rectosigmoid segment is important and useful for the purpose of management. Most low-lying rectal foreign objects are reachable by the examining finger and can be removed per anum whereas those higher up in the sigmoid colon can prove to be difficult to retrieve[1,2,7,13,14]. Foreign bodies that are impacted above the rectum are usually not easily visualized and therefore transanal retrieval is difficult[1,2,7,13,14]. Generally speaking, a foreign body located below the rectosigmoid junction that is easily palpable by the clinician’s examining finger can be extracted in the ED. However, an uncooperative and anxious patient with associated anal sphincter muscles contractions will make ED extraction undesirable. The use of anaesthesia in the treatment of these patients reduces anal sphincter muscles spasm and therefore improves direct visualization and good exposure with a successful chance of extraction per anum[1,8].

There has been a significant evolution of the techniques addressing the various management challenges of wide spectrum of different types of objects impacted in the rectum over the last few years[1,2,4,8,10,14,16]. The majority of retained low-lying foreign bodies can be removed with a guided grasping forceps or a clamp introduced through a proctosigmoidoscope. This approach can be aided by an initial examining finger manoeuvre to disengage the impacted object from the oedematous anorectal mucosa[1,8]. The majority of our patients in this study required their retained rectal objects to be removed in the operating theatre under direct vision with proctosigmoidoscope using a grasping forceps or a small Keilland’s forceps. All of them underwent successful transanal retrieval with no need for laparoscopy or laparotomy.

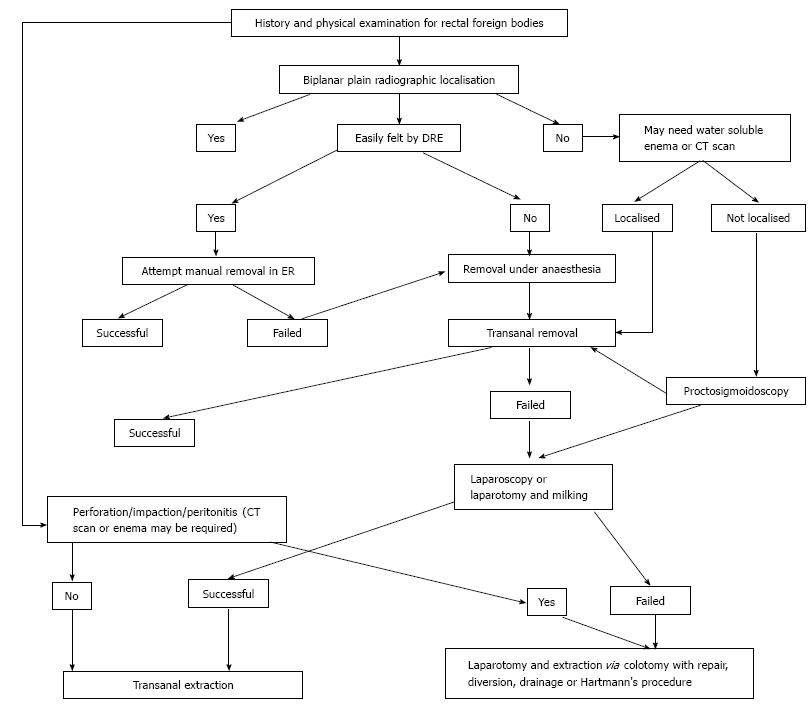

The failure of transanal retrieval of impacted foreign bodies in the rectum can be predicted preoperatively. Lake et al[4] in their experience cited several factors responsible for failure of transanal removal including the impaction of a an object longer than 10 cm, hard or sharp objects, objects that have migrated upward into the sigmoid colon and those that have been impacted for more than 2 d. There are specific indications for the use of emergency laparotomy for extraction of impacted objects including failure of attempts at transanal removal, presence of perforation and/or peritonitis[1,2,4,8,16]. The use of minimally invasive operative techniques for impacted rectosigmoid foreign bodies has been described which is a combination of laparoscopic downward milking of the object followed by per anal extraction[1,2,17-19]. This approach however is only recommended for smooth foreign bodies and if successful, avoids the need for a full laparotomy and provides the benefit of early discharge from the hospital[1,2,17-19]. Figure 2 is adapted from reference 1.

In conclusion, this study confirms a rising trend in the number of patients with retained rectal foreign bodies with hospital presentations and most of these objects were used for erotic stimulation. There was also a slightly higher female population in the current study than previously reported and this may be the emerging trend of this entity. It is very much likely that the increasing trend would be encountered in most hospitals and therefore, the clinicians in the emergency settings need to be well informed about the approach to the care of patients with retained rectal foreign bodies.

Hospital presentation with retained rectal foreign bodies is no longer rare although concrete epidemiological data are still lacking. They are usually encountered in the adults and are either inserted intentionally or non-intentionally. The delay in the presentation and the associated patient’s vague history usually lead to significant diagnostic and management challenges.

There are recent anecdotal reports suggesting an increasing trend in the hospital presentations with impacted foreign bodies in the rectum. The present authors’ and other authors’ prediction from the previous published reports was a likelihood of an increasing presentation with the use of different objects for anorectal eroticism. Therefore, the clinicians in the emergency settings should be well familiar with the approach and the principles of care of these patients.

The authors predict that from the current study and the paucity of the available published epidemiological data that there is likely going to be an increasing trend in the incidence and presentations with the retained objects in the rectum.

The diagnosis and treatment patients presenting to hospital rectal foreign bodies should be orderly and methodical including safe retrieval and post-extraction period of observation. The desired ultimate outcome for every case is a safe and successful per anum extraction of foreign body, in a manner respecting the patients’ right to dignity, privacy and confidentiality.

Retained lower GIT foreign bodies may be located low or high based on their positions relative to the to the rectosigmoid junction. Most low-lying rectal foreign objects are easily reachable by the examining finger and can be removed per anum whereas those higher up in upper rectum or sigmoid colon may be difficult to reach and retrieved.

This is an interesting case series of rectal foreign bodies.

| 1. | Ayantunde AA. Approach to the diagnosis and management of retained rectal foreign bodies: clinical update. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goldberg JE, Steele SR. Rectal foreign bodies. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:173-184, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kurer MA, Davey C, Khan S, Chintapatla S. Colorectal foreign bodies: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:851-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lake JP, Essani R, Petrone P, Kaiser AM, Asensio J, Beart RW. Management of retained colorectal foreign bodies: predictors of operative intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1694-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Safioleas M, Stamatakos M, Safioleas C, Chatziconstantinou C, Papachristodoulou A. The management of patients with retained foreign bodies in the rectum: from surgeon with respect. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:352-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Coskun A, Erkan N, Yakan S, Yıldirim M, Cengiz F. Management of rectal foreign bodies. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rodríguez-Hermosa JI, Codina-Cazador A, Ruiz B, Sirvent JM, Roig J, Farrés R. Management of foreign bodies in the rectum. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ayantunde AA, Oke T. A review of gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:735-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cohen JS, Sackier JM. Management of colorectal foreign bodies. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:312-315. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Koornstra JJ, Weersma RK. Management of rectal foreign bodies: description of a new technique and clinical practice guidelines. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4403-4406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Traub SJ, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Body packing--the internal concealment of illicit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2519-2526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Smith MT, Wong RK. Foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:361-382, vii. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Clarke DL, Buccimazza I, Anderson FA, Thomson SR. Colorectal foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:98-103. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Huang WC, Jiang JK, Wang HS, Yang SH, Chen WS, Lin TC, Lin JK. Retained rectal foreign bodies. J Chin Med Assoc. 2003;66:607-612. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hellinger MD. Anal trauma and foreign bodies. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1253-1260. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Eftaiha M, Hambrick E, Abcarian H. Principles of management of colorectal foreign bodies. Arch Surg. 1977;112:691-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Berghoff KR, Franklin ME. Laparoscopic-assisted rectal foreign body removal: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1975-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rispoli G, Esposito C, Monachese TD, Armellino M. Removal of a foreign body from the distal colon using a combined laparoscopic and endoanal approach: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1632-1634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Han HJ, Joung SY, Park SH, Min BW, Um JW. Transanal rectal foreign body removal using a SILS port. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:e157-e158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Konishi T, Odagiri H, Silva M, Wani IA S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ