Published online Oct 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.273

Peer-review started: February 13, 2015

First decision: May 13, 2015

Revised: June 1, 2015

Accepted: September 10, 2015

Article in press: September 16, 2015

Published online: October 27, 2015

Processing time: 262 Days and 18.8 Hours

AIM: To describe the anal cushion lifting (ACL) method with preliminary clinical results.

METHODS: Between January to September 2007, 127 patients who received ACL method for hemorrhoid was investigated with informed consent. In this study, three surgeons who specialized in anorectal surgery performed the procedures. Patients with grade two or more severe hemorrhoids according to Goligher’s classification were considered to be indicated for surgery. The patients were given the choice to undergo either the ACL method or the ligation and excision method. ACL method is an original technique for managing hemorrhoids without excision. After dissecting the anal cushion from the internal sphincter muscle, the anal cushion was lifted to oral side and ligated at the proper position. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients were recorded including complications after surgery.

RESULTS: A total of 127 patients were enrolled. Their median age was 42 (19-84) years, and 74.8% were female. In addition, more than 99% of the patients had grade 3 or worse hemorrhoids. The median follow-up period was 26 (0-88) mo, and the median operative time was 15 (4-30) min. After surgery, analgesics were used for a median period of three days (0-21). Pain control was achieved using extra-oral analgesic drugs, although some patients required intravenous injections of analgesic drugs. The median duration of the patients’ postoperative hospital stay was 7 (2-13) d. A total of 10 complications (7.9%) occurred. Bleeding was observed in one patient and was successfully controlled with manual compression. Urinary retention occurred in 6 patients, but it disappeared spontaneously in all cases. Recurrent hemorrhoids developed in 3 patients after 36, 47, and 61 mo, respectively. No anal stenosis or persistent anal pain occurred.

CONCLUSION: We consider that the ACL method might be better than all other current methods for managing hemorrhoids.

Core tip: Hemorrhoidectomy, e.g., the ligation and excision method, is still the gold standard surgical technique for hemorrhoids. All of the classical surgical techniques for hemorrhoids are fundamentally based on the resectioning of the hemorrhoids, which can result in anal stenosis. We developed the anal cushion lifting method, in which the prolapsed anal cushion is restored to its original position, as a way of preventing various postoperative complications. We recruited 127 patients and conducted a prospective clinical study. By the end of the study, none of the patients had suffered anal stenosis or persistent anal pain.

- Citation: Ishiyama G, Nishidate T, Ishiyama Y, Nishio A, Tarumi K, Kawamura M, Okita K, Mizuguchi T, Fujimiya M, Hirata K. Anal cushion lifting method is a novel radical management strategy for hemorrhoids that does not involve excision or cause postoperative anal complications. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(10): 273-278

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i10/273.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.273

Hemorrhoids are the most common symptomatic disorder among adults, although its exact incidence is unclear[1-4]. In the Austrian national screening program, 39% of the adult population was found to have symptomatic hemorrhoids[5]. However, hospital-based proctoscopic studies have suggested that after including asymptomatic cases the prevalence of hemorrhoids is 86%[6]. Hemorrhoids can be caused by abnormal downward displacement of the anal cushions due to straining associated with constipation or traditional lifestyles. Thereafter, the hemorrhoids gradually enlarge until they become symptomatic[1-4]. Surgical management primarily aims to control hemorrhoid prolapse in cases in which conservative treatment has been ineffective[1-4,7]. In addition to symptom management, anal function should be maintained after surgery.

Hemorrhoidectomy is still the gold standard surgical procedure for hemorrhoids, and various techniques have been developed such as the Milligan-Morgan (MM), Ferguson, and stapled hemorrhoidectomy (procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids) methods, etc[2]. All of the classical surgical techniques for treating hemorrhoids aim to resect the hemorrhoids together with the anoderm and the perianal epithelium, which occasionally causes anal stenosis and persistent anal pain[8]. In a previous study, anal stenosis occurred in 2.4%-5% of cases in which the Ferguson or MM method was employed[9,10]. Furthermore, severe anal stenosis was reported to occur in 1.8% of cases in which the MM method was performed[11]. In addition to anal stenosis, postoperative pain, bleeding, and long hospital stays are clinical problems that need to be overcome[1]. We developed a novel surgical method for treating hemorrhoids, in which the prolapsed anal cushion is returned to its native position and sutured, that does not involve any resectioning of the anoderm. The main advantages of this technique, which we have named the anal cushion lifting method [the anal cushion lifting (ACL) method], are that it is very simple and does not cause anal stenosis or persistent pain. Herein, we describe the ACL method in detail and report preliminary clinical results for the procedure.

We used the ACL method to treat 127 patients who gave their informed consent from January to September 2007. In this study, three surgeons who specialized in anorectal surgery (board certified anorectal surgeons belonging to the Japan Society of Coloproctology; No. 1857 for Ishiyama G, No. 0021S for Ishiyama Y, and No. 1829 for Tarumi K) performed the procedures. Before the study, we decided that the study would be terminated if any of the patients suffered anal stenosis or persistent pain. Otherwise, it would be terminated at the end of the month in which the 100th patient was recruited. Patients with grade two or more severe hemorrhoids according to Goligher’s classification were considered to be indicated for surgery (Table 1)[12]. The patients were given the choice to undergo either the ACL method or the ligation and excision (LE) method. During the study period, 189 patients selected the LE method. The study protocol was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all of the patients gave their informed consent.

| Grade | Physical findings |

| I | Prominent hemorrhoidal vessels, no prolapse |

| II | Prolapse with Valsalva maneuver; spontaneous reduction |

| III | Prolapse with Valsalva maneuver; requires manual reduction |

| IV | Chronically prolapsed; manual reduction ineffective |

Caudal epidural anesthesia or low lumber anesthesia was used. The procedure was usually performed whilst the patient was in the prone position, but the Jack-knife position was sometimes selected in cases involving patients with muscular bodies. A good surgical field was obtained by taping and pulling using packing tape. The anal field was sterilized using disinfectant before the operation.

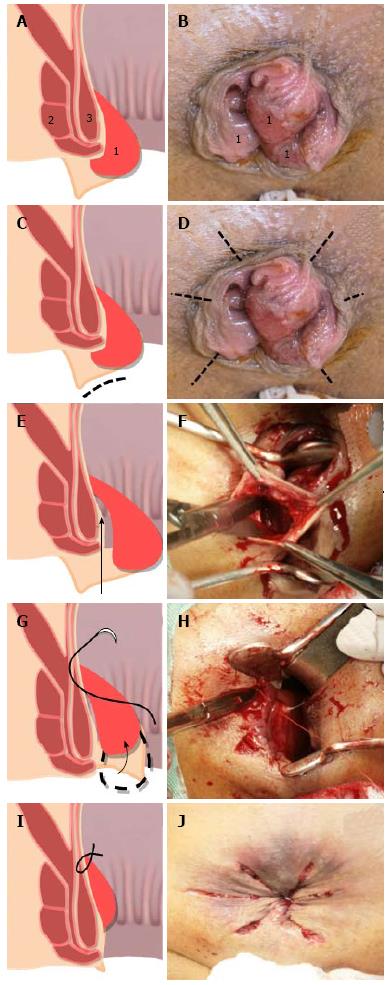

After careful assessment of any anal conditions or other disorders that the patient was suffering from, the anus was gently stretched using the fingers. Some patients had already suffered stenosis, which resulted in the internal sphincter exhibiting reduced elasticity muscle due to fibrosis. This manual manipulation procedure partially restored the hemorrhoids to their native position (Figure 1A and B).

Five to six small straight incisions of 1-2 cm in length were made in the swollen epithelium of the perianal skin (Figure 1C and D). Then, we dissected the tissue between the anal cushion and internal sphincter muscle (Figure 1E and F). No significant bleeding occurred, providing that the dissection was performed accurately. In most cases, the hemorrhoids were spontaneously restored to their native position after this part of the procedure.

Next, we sutured the cranial side and middle portion of the anal cushion to the internal sphincter muscles (Figure 1G and H) using 3-0 VICRYL® Rapide sutures (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Blue Ash, OH, United States). The anal cushion shrank after its circumferential ligation, and the anal prolapse was completely resolved (Figure 1I and J).

No antibiotics were administered after the surgery. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) were administered on the first three postoperative days unless the patient experienced pain. If the patient complained of pain, intravenous analgesic injections or extra-oral analgesic medication were administered, and NSAID were administered the next day.

All data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

A total of 127 patients were enrolled in this study (Table 2). Their median age was 42 years old, and 74.8% were female. In addition, more than 99% of the patients had grade 3 or worse hemorrhoids. The median follow-up period was 26 mo, and the median operative time was 15 min. After surgery, analgesics were used for a median period of three days. Pain control was achieved using extra-oral analgesic drugs in most cases, and such drugs were administered a median of three times, although some patients required intravenous injections of analgesic drugs. The median duration of the patients’ postoperative hospital stay was 7 d.

| Characteristics and outcomes | Values (95%CI) |

| Age (yr) | 42 (19-84) |

| Gender (male:female) | 32 (25.2%): 95 (74.8%) |

| Grade (2:3:4) | 1 (0.8%): 113 (89.0%): 13 (10.2%) |

| Follow-up time (mo) | 26 (0-88) |

| Operative time (min) | 15 (4-30) |

| Duration of analgesic treatment (d) | 3 (2-13) |

| No. of intravenous analgesic injections | 0 (0-9) |

| No. of doses of extra-oral analgesic medication administered | 3 (0-21) |

| Duration of hospital stay (d) (Time to resumption of normal activity) | 7 (2-13) |

| Total complications | 10/127 (7.9%) |

| Bleeding | 1 (0.8%) |

| Urinary retention | 6 (4.7%) |

| Recurrence | 3 (2.4%) |

| Anal stenosis | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Persistent anal pain during hospital stay | 0 |

A total of 10 complications occurred. Bleeding was observed in one patient and was successfully controlled with manual compression. Urinary retention occurred in 6 patients, but it disappeared spontaneously in all cases. Recurrent hemorrhoids developed in 3 patients after 36, 47, and 61 mo, respectively. No anal stenosis or persistent anal pain occurred.

We developed a novel surgical procedure for hemorrhoids, which we named the ACL method. In the present study, the clinical outcomes of the ACL method; i.e., its complications, the operative time, the number of postoperative analgesic injections required, the frequency of postoperative oral analgesic medication use, the duration of postoperative analgesic treatment, and the duration of the postoperative hospitalization period, were acceptable.

Classical hemorrhoidectomy and other surgical techniques for treating hemorrhoids basically involve the ligation of the feeding artery[1]. However, if the blood supply to the anoderm and perianal tissue is cut off due to arterial ligation then these tissues will become necrotic. On the other hand, the ACL method is based on the ligation of the superficial anal cushion and preserves the arterial supply. So, no necrosis occurs after surgery, and complete wound healing can be achieved. In addition, the importance of preserving the anoderm has been stressed in reports about various other techniques, and anoderm preservation has been reported to reduce the risk of anal stenosis and anal pain after surgery[13]. The ACL method does not involve any excision of the anoderm. Our only concern about the ACL method was whether the anal cushion would become congested after surgery, which could lead to a worsening of the patient’s symptoms. However, the collateral venous plexus is preserved in the ACL method, so the anal cushion never becomes congested.

Recently, a similar technique, the Z-shaped ligation method for anal hemorrhoids, was reported by Gemici et al[14]. Their concept is derived from sclerotherapy, which aims to treat vascular structures alone. The difference between our ACL method and the Z-shaped ligation method is that we dissected the tissue between the anal cushion and internal sphincter muscle and they did not. Both procedures involve similar ligation sites and exhibited similar complications rates. Our ACL method might be more painful than the Z-shaped ligation method as it requires incisions and dissection. However, small radial incisions do not cause severe anal pain, and dissection itself does not cause anal pain. The recurrence rate of the ACL method seems to be lower than that of the Z-shaped ligation method, which is reasonable. As en-bloc ligation of the anal cushion can only be achieved after the dissection of the tissue, both methods prove that ligation of the anal cushion is sufficient for managing hemorrhoids.

The anal pain experienced after the LE method is considered to be caused by the anal duct being subjected to excessive tension after surgery[8]. Excision of the anoderm and perianal epithelium itself can also cause postoperative anal pain[13]. On the other hand, the ACL method causes minimal postoperative anal pain, as it does not involve the application of tension to the anal duct. In addition, the total length of the incisions made during the ACL method is shorter than the total length of the incisions made during classical methods. Furthermore, the better blood supply provided by the ACL method helps to prevent persistent pain after surgery. In fact, the patients that underwent the ACL method did not have to stay in hospital for as long and were able to return to normal life faster than those that underwent the classical method. Also, the patients who underwent the ACL method required fewer analgesic injections, took analgesic medications less often and for shorter periods, and experienced less pain than those that underwent the LE method.

As we have shown, the ACL method is a very simple technique that does not cause significant bleeding. The classical surgical methods for hemorrhoids are based on the excision of the anoderm and ligation of the feeding artery[2,3]. In such procedures, the incisions have to be meticulously planned in order to prevent skin tags. However, the ACL method involves simple dissection of the tissue between the anal cushion and the inner sphincter muscle followed by the ligation of the anal cushion. Therefore, in the present study the total operation time for the ACL method was shorter than that for the LE method.

The most important aspect of the classical technique is the extent of the excision. In cases involving significant anal prolapse, a large amount of skin has to be excised to achieve good anal esthetics. However, the risk of postoperative stenosis is increased if the excision is too extensive. On the other hand, the ACL method is not affected by such concerns. The clinical outcomes of two excision methods, the MM and Ferguson methods, are summarized in Table 3. In the present study, the ACL method exhibited a lower complications rate than the abovementioned excision methods. Interestingly, all of the patients’ anal cushions eventually shrank after the ACL method. This makes sense as the ACL method preserves collateral venous vessels, which facilitates anal cushion shrinkage and the restoration of normal function.

| Ref. | Bikhchandani et al[15] | Shalaby et al[10] | Bulus et al[16] | Correa-Rovelo et al[9] |

| Method | MM | MM | Ferguson | Ferguson |

| No. of patients | 42 | 100 | 71 | 42 |

| Operative time (min) (mean ± SD) | 45.2 ± 5.4 | 19.7 ± 4.7 | 25.5 ± 7.7 | 38.1 ± 12.9 |

| Complications (%) | ||||

| Bleeding | 2.4 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 0 |

| External tags | 2.4 | 1.0 | - | 4.9 |

| Anal stenosis | 0 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 2.4 |

| Infection | 0 | - | 1.4 | - |

| Urinary retention | 16.7 | 14.0 | 28.2 | 7.1 |

| Recurrence | 5.0 | 2.0 | 8.5 | 0 |

We consider that the ACL method might be better than all other current methods for managing hemorrhoids, including the Z-shaped ligation method. However, we could not prove that the ACL method has definitive clinical advantages in the present study. Therefore, a large prospective study should be designed to confirm the clinical advantages of the ACL method over other methods.

We thank all of the medical staff at Ishiyama Hospital in Sapporo for their contribution to the perioperative management of the present cases.

Hemorrhoidectomy is still the gold standard surgical procedure for hemorrhoids, and various hemorrhoidectomy procedures, such as the ligation and excision method, etc., have been proposed. All of the classical surgical techniques for hemorrhoids are based on resecting the hemorrhoids together with the anoderm and the perianal epithelium, which occasionally causes anal stenosis and persistent anal pain. The authors present a novel surgical approach, in which the prolapsed anal cushion is restored to its native position that does not cause postoperative stenosis or persistent anal pain.

Classical hemorrhoidectomy and other surgical techniques for treating hemorrhoids cause postoperative stenosis or persistent anal pain. On the other hand, the anal cushion lifting (ACL) method is based on the ligation of the superficial anal cushion and preserves the arterial supply. So, no necrosis occurs after surgery, and complete wound healing can be achieved.

The ACL method is an original novel surgical technique which causes no anal stenosis and persistent pain after surgery.

The ACL method might take place classical technique for surgical management of the hemorrhoids in future.

Hemorrhoidectomy, e.g., the ligation and excision method, is still the gold standard surgical technique for hemorrhoids. The ACL method is novel surgical technique for hemorrhoids.

The authors have presented interesting results on the development of a new surgical method for the management of hemorrhoid which shows superiority to the current surgical techniques in terms of operation time, post-operative pain and recovery.

| 1. | Altomare DF, Giuratrabocchetta S. Conservative and surgical treatment of haemorrhoids. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Lohsiriwat V. Approach to hemorrhoids. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Madoff RD, Fleshman JW. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1463-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Milligan ETC, Morgan CN, Jones LE. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and operative treatment of haemorrhoids. Lancet. 1937;1:1119-1124. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, Stift A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Haas PA. The prevalence of confusion in the definition of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:290-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lehur PA, Pierres C, Dert C. Haemorrhoids: 21st-century management. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Katdare MV, Ricciardi R. Anal stenosis. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:137-145, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Correa-Rovelo JM, Tellez O, Obregón L, Miranda-Gomez A, Moran S. Stapled rectal mucosectomy vs. closed hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1367-1374; discussion 1374-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shalaby R, Desoky A. Randomized clinical trial of stapled versus Milligan-Morgan haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1049-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gravié JF, Lehur PA, Huten N, Papillon M, Fantoli M, Descottes B, Pessaux P, Arnaud JP. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy versus milligan-morgan hemorrhoidectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial with 2-year postoperative follow up. Ann Surg. 2005;242:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clinical Practice Committee, American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1461-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Theodoropoulos GE, Michalopoulos NV, Linardoutsos D, Flessas I, Tsamis D, Zografos G. Submucosal anoderm-preserving hemorrhoidectomy revisited: a modified technique for the surgical management of hemorrhoidal crisis. Am Surg. 2013;79:1191-1195. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gemici K, Okuş A, Ay S. Vascular Z-shaped ligation technique in surgical treatment of haemorrhoid. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:10-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bikhchandani J, Agarwal PN, Kant R, Malik VK. Randomized controlled trial to compare the early and mid-term results of stapled versus open hemorrhoidectomy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:56-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bulus H, Tas A, Coskun A, Kucukazman M. Evaluation of two hemorrhoidectomy techniques: harmonic scalpel and Ferguson’s with electrocautery. Asian J Surg. 2014;37:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Hadianamrei R, Picchio M S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/