Published online Mar 27, 2014. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i3.47

Revised: January 5, 2014

Accepted: February 16, 2014

Published online: March 27, 2014

Processing time: 119 Days and 19.5 Hours

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) results from incomplete involution of the proximal portion of the vitelline (also known as the omphalomesenteric) duct during weeks 5-7 of foetal development. Although MD is the most commonly diagnosed congenital gastrointestinal anomaly, it is estimated to affect only 2% of the population worldwide. Most cases are asymptomatic, and diagnosis is often made following investigation of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, inflammation or obstruction that prompt clinic presentation. While MD range in size from 1-10 cm, cases of giant MD (≥ 5 cm) are relatively rare and associated with more severe forms of the complications, especially for obstruction. Herein, we report a case of giant MD with secondary small bowel obstruction in an adult male that was successfully managed by surgical resection and anastomosis created with endoscopic stapler device (80 mm, endo-GIA stapler). Patient was discharged on post-operative day 6 without any complications. Histopathologic examination indicated Meckel’s diverticulitis without gastric or pancreatic metaplasia.

Core tip: The most commonly diagnosed congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract is Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), which occurs upon failure of the omphalomesenteric duct to regress and involute. MD can remain asymptomatic, and cases are generally diagnosed incidentally or upon investigation of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, inflammation, or obstruction for both paediatric and adult cases. It is estimated that as little as 4% of cases manifest complications, and obstruction is the most common presenting symptom in adults. In this case study, we report a case of giant MD with secondary small bowel obstruction in an adult male that was successfully managed by surgical resection and anastomosis created with endoscopic stapler.

- Citation: Akbulut S, Yagmur Y. Giant Meckel’s diverticulum: An exceptional cause of intestinal obstruction. World J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 6(3): 47-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v6/i3/47.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v6.i3.47

The most commonly diagnosed congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract is Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), which occurs upon failure of the vitelline (also known as the omphalomesenteric) duct to regress and involute[1-3]. Accumulated experience with surgical treatment of MD (using both open and laparoscopic procedures) has led to the clinical “rule of 2” for symptomatic cases, whereby the anatomical deformity (with estimated prevalence in 2% of the population) is most frequently located 2 feet from the ileocaecal junction and is 2 inches long[2]. MD can remain asymptomatic, and cases are generally diagnosed incidentally or upon investigation of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, inflammation, or obstruction for both paediatric and adult cases[1].

It is estimated that as little as 4% of cases manifest complications, and obstruction is the most common presenting symptom in adults[1]. There is evidence that severity of symptoms correlates with MD size. Ninety percent of the reported MDs are between 1 and 10 cm, the average size being 3 cm. MDs ≥ 5 cm are classified as giant MD, are relatively rare, and may be more prone to complications[1]. Here, we report a case of giant MD which was diagnosed in an adult male with small bowel obstruction and successfully managed by resection.

A 23-year-old male patient presented at the Emergency Department with a complaint of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that had persisted for 5 d and increased in severity over the last 24 h. The patient reported no faecal or gas discharge during the previous 48 h. History taking upon admission revealed that the patient had visited hospitals frequently for many years with similar gastrointestinal complaints as well as bloating. The patient’s abdomen was remarkably distended and initial clinical assessment indicated hypovolemia. Physical examination revealed significant bowel sounds and substantial abdominal rebound pain, both more robust in the periumbilical area. Laboratory testing showed increased white blood cell count (11.8 × 103/μL; normal range: 4.1 × 103-11.2 × 103), haemoglobin (17.0 g/dL; 12.5-16.0), haematocrit (49.6%; 37.0-47.0) and creatinine (1.4 mg/dL; 0.4-1.2), but normal blood urea nitrogen (27 mg/dL; 10-50). Abdominal X-ray indicated remarkably high air-fluid levels (Figure 1).

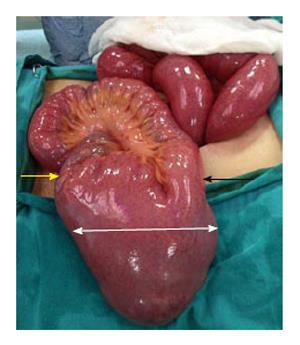

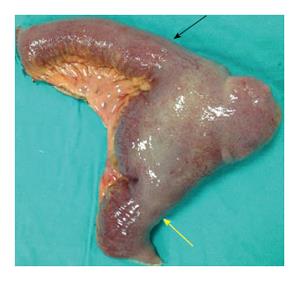

An emergency laparotomy was performed and revealed oedema throughout the entire small bowel, dilation of small bowel segments, and a giant MD (27 cm long and 6 cm wide) on the antimesenteric border of the small bowel at 80 cm proximal to the ileocaecal valve (Figure 2). The diverticulum’s tip was strongly adhered to the parietal peritoneum of the abdominal wall at the site of the pelvis, having been pushed up against this site due to the MD’s excessively large size and high-volume intestinal content. No other obstruction was observed in the gastrointestinal tract. Resection of the small bowel was performed with a linear stapler and an ileoileal anastomosis was generated using a 80 mm endo-GIA stapler (Figure 3). The resection was completed without incident, and the patient was discharged on post-operative day 6 without any complications. Pathology findings indicated diverticulitis without gastric or pancreatic metaplasia.

MD is a true diverticulum, comprising all three layers of the small intestine. Compared to the overall incidence of 0.14%-4.50% (estimated by autopsy findings and retrospective studies)[4], giant MD are rare[5]. The largest giant MDs reported have been > 100 cm long[6], 96 cm long[7], 85 cm long[8], and 66 cm long[9,10].

In adult cases of MD, obstruction is the most frequently reporting presenting symptom[11-14] and can be caused by either the diverticulum’s attachment to the umbilicus, abdominal wall or other viscera by a fibrous band or by interference due to the mobility of an unattached diverticulum[11]. Though first hypothesized in 1902[13], these potential reasons for MD-caused intestinal obstruction remain the features by which MD cases are classified. The obstructions associated with a free or unattached diverticulum, or having only one attachment to the intestine, represent first MD type, and obstructions associated with an attached diverticulum, including through its terminal ligament, to the abdominal wall or intestinal viscus, represent the second type. Between these two types, the former is much rarer.

When the congenital malformation occurs, the free diverticulum forms a volvulus with a loop, twisting the gut structure. Adhesions commonly form between the two arms of the twist, making an obstruction. Subsequent inflammation of the diverticulum further promotes constriction of the bowel. Furthermore, an unattached, distended diverticulum may cause movement of the looped intestine so that a kink forms in the intestine at the attachment point of the diverticulum; this event could lead to an obstruction without any concomitant structural changes in the intestinal wall. Persistence of such kinking may ultimately cause necrosis of the involved and proximal gut tissues. Other potential aetiologies of MD-related intestinal obstructions exist. For example, the obstruction may be caused by twisting of the bowel along its long axis at the point of the diverticulum’s origin, by chronic inflammation of the diverticulum and its adjacent bowel, or by inversion of the mucous membrane alone, or of the entire diverticulum, with or without invagination.

Several case reports of MD-related obstructions have described strangulation caused by an adherent diverticulum. Many causes of such an event have been proposed. First, the adherent diverticulum itself may act as a constricting band, such as an adventitious band or a peritoneal adhesion. Second, the adherent diverticulum may have resulted from looping and twisting of the gut in upon itself, forming a volvulus. Third, a volvulus of the attached diverticulum may itself represent a physical obstruction of the intestine. Finally, the diverticular band may become tensely drawn under certain conditions[13].

In a review of 402 patients with MD, 16.9% of the patients were found to have demonstrated symptoms that are considered clinical references for diverticulum[14], with obstruction of the small intestine, and inflammation and bleeding of the lower gastrointestinal tract accounting for 90% of those presenting symptoms. In another study of 34 MD cases, the most common complications were intestinal obstruction (37%), intussusception (14%), inflammation, and rectal bleeding (12%); interestingly, intussusception and volvulus were associated with those patients having intestinal obstruction[15].

For the current case of giant MD, the diverticulum was large in diameter, long in length, and adherent (causing a small bowel obstruction). The structural features of a MD provide clues to the type of complications it may cause. For example, diverticulitis and torsion are common complications observed with long MDs that have a narrow base, while short MDs that have a stumpy base are more often associated with intussusception[16]. Thus, an elongated variant with a narrow neck is more likely to result in torsion, whereas a short, wide-base diverticula may promote foreign body entrapment.

Cullen et al[17] studied the outcomes of diverticulectomy surgical management of MD-related complications and determined that the operative mortality and morbidity rates were 2% and 12%, respectively, and that the cumulative risk of long-term post-operative complications was 7%; in contrast, analysis of patients receiving incidental diverticulectomy showed that the operative mortality, morbidity, and risk of long-term post-operative complications were lower (1%, 2%, and 2%, respectively). It is generally recommended that MD discovered incidentally during operation should be removed, regardless of the patient’s age.

In conclusion, this report describes a very rare form of acute small bowel obstruction secondary to giant MD encircling the terminal ileum, providing novel insights into this condition and describing its successful management by surgical resection.

Clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and no faecal or gas discharge.

Acute abdomen, mechanical small bowel obstructions.

Intestinal malrotation, congenital anomalous bands, tumor obstruction.

Laboratory tests showed a leukocytosis (11800/μL; 4100-11200), haemoglobin (17.0 g/dL; 12.5-16.0), haematocrit (49.6%; 37.0-47.0) and creatinine (1.4 mg/dL; 0.4-1.2).

An abdominal X-ray radiography indicated remarkably high air-fluid levels.

Pathology findings indicated Meckel’s diverticulitis without gastric or pancreatic metaplasia.

Limited ileal resection and end-to-end anastomosis created with stapler device.

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), a remnant of the vitelline duct that normally disappears at the end of the seventh week of gestation, is the most common congenital abnormality of the small intestine. It arises from the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum as a true diverticulum that contains all layers of the intestinal wall.

This is a well written case report on a farly common subject. It is well know that MD can couse intestinal obstruction and can reach fairly large dimensions, depending on the duration of the sub-occlusive symptoms.

P- Reviewers: Hiraki M, Iacono C, Nigri G S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Harvin HJ, Francis IR. Imaging manifestations of Meckel’s diverticulum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sagar J, Kumar V, Shah DK. Meckel’s diverticulum: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:501-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cartanese C, Petitti T, Marinelli E, Pignatelli A, Martignetti D, Zuccarino M, Ferrozzi L. Intestinal obstruction caused by torsed gangrenous Meckel’s diverticulum encircling terminal ileum. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3:106-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Limas C, Seretis K, Soultanidis C, Anagnostoulis S. Axial torsion and gangrene of a giant Meckel’s diverticulum. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:67-68. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Torii Y, Hisatsune I, Imamura K, Morita K, Kumagaya N, Nakata H. Giant Meckel diverticulum containing enteroliths diagnosed by computed tomography and sonography. Gastrointest Radiol. 1989;14:167-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tisdall FF. An unusual Meckel’s diverticulum as a cause of intestinal hemorrhage. Am J Dis Child. 1928;36:1218-1223. |

| 7. | Chaffin L. Surgical emergencies during childhood caused by meckel’s diverticulum. Ann Surg. 1941;113:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Moll HH. Giant Meckel’s diverticulum (33 ½ inches long). Br J Surg. 1926;14:176-179. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goldstein M, Cragg RW. Elongated Meckel's Diverticulum In A Chıld. Am J Dis Child. 1938;55:128-134. |

| 10. | Moses WR. Meckel’s diverticulum; report of two unusual cases. N Engl J Med. 1947;237:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weinstein EC, Cain JC, Remine WH. Meckel‘s diverticulum: 55 years of clinical and surgical experience. JAMA. 1962;182:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Turgeon DK, Barnett JL. Meckel’s diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:777-781. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Halstead AE. IV. Intestinal Obstruction from Meckel’s Diverticulum. Ann Surg. 1902;35:471-494. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mackey WC, Dineen P. A fifty year experience with Meckel’s diverticulum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;156:56-64. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Yamaguchi M, Takeuchi S, Awazu S. Meckel’s diverticulum: Investigation of 600 patients in Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1978;136: 247-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Caiazzo P, Albano M, Del Vecchio G, Calbi F, Loffredo A, Pastore M, De Martino C, Di Lascio P, Tramutoli PR. Intestinal obstruction by giant Meckel’s diverticulum. Case report. G Chir. 2011;32:491-494. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, Hodge DO, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Surgical management of Meckel's diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population-based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220:564-568; discussion 568-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |