Published online Nov 27, 2014. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v6.i11.229

Revised: September 16, 2014

Accepted: October 14, 2014

Published online: November 27, 2014

Processing time: 133 Days and 16.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy (DA) in acute surgical patients admitted to a District General Hospital.

METHODS: The case notes of all acute surgical patients admitted under the surgical team for a period of two weeks were reviewed for the data pertaining to the admission diagnoses, relevant investigations and final diagnoses confirmed by either surgery or various other diagnostic modalities. The diagnostic pathway was recorded from the source of referral [general practitioner (GP), A and E, in-patient] to the correct final diagnosis by the surgical team.

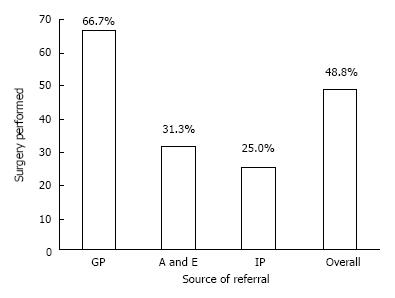

RESULTS: Forty-one patients (23 males) with acute surgical admissions during two weeks of study period were evaluated. The mean age of study group was 61.05 ± 23.24 years. There were 111 patient-doctor encounters. Final correct diagnosis was achieved in 85.4% patients. The DA was 46%, 44%, 50%, 33%, 61%, 61%, and 75% by GP, A and E, in-patient referral, surgical foundation year-1, surgical senior house officer (SHO), surgical registrar, and surgical consultant respectively. The percentage of clinical consensus diagnosis was 12%. Surgery was performed in 48.8% of patients. Sixty-seven percent of GP-referred patients, 31% of A and E-referred, and 25% of the in-patient referrals underwent surgery. Surgical SHO made the most contributions to the primary diagnostic pathway.

CONCLUSION: Approximately 85% of acute surgical patients can be diagnosed accurately along the diagnostic pathway. Patients referred by a GP are more likely to require surgery as compared to other referral sources. Surgical consultant was more likely to make correct surgical diagnosis, however it is the surgical SHO that contributes the most correct diagnoses along the diagnostic pathway.

Core tip: Approximately 85% of acute surgical patients can be diagnosed accurately along the diagnostic pathway. One of the strategies to reduce diagnostic error is to develop pathways for feedback. It is particularly important to develop feedback pathways for the junior doctors, as it has been shown that less experienced doctors tend to most over-estimate their diagnostic accuracy. With anonymity removed, the basic design of this study seems well suited to enable feedback to each physician involved in the care of an acute surgical patient.

- Citation: Sajid MS, Hollingsworth T, McGlue M, Miles WF. Factors influencing the diagnostic accuracy and management in acute surgical patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 6(11): 229-234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v6/i11/229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v6.i11.229

Diagnostic errors have recently begun to receive more attention as a preventable source of patient harm. Diagnostic errors are estimated to account for 80000-160000 deaths per year[1]. Misdiagnosis has been the leading cause of medical malpractice payments over the last 25 years, making up 28.6% of claims and 35.2% of total payouts[1]. Missed, incorrect, or delayed diagnoses are estimated to occur in 15% of clinical cases, accounting for 8%-20% of adverse medical events[2]. Diagnosis is the most critical of a physician’s skills. Nuland previously so perfectly stated, “It is every doctor’s measure of his abilities; it is the most important ingredient in his professional self image”[3], yet even with such a high regard for diagnostic accuracy, there remains an absence of ownership when it comes to quality and safety systems to reduce the diagnostic errors[4]. Most of the studies attempting to quantify the diagnostic error have either been retrospective studies examining adverse events, such as malpractice claims and autopsy reports, or have been experimental studies comparing multiple physician responses to the same diagnostically challenging scenarios, which are often not reflective of the actual clinical environment[2]. Therefore, the true prevalence of diagnostic errors and inability to make right diagnosis along the acute surgical pathway has been notoriously difficult to evaluate[2,5].

Preventable diagnostic errors can result form the system-related factors and various cognitive factors. A published article on the prevalence of diagnostic error in 100 clinical cases revealed the system-related factors result in 65% diagnostic inaccuracies and cognitive factors in 74%[6] of the diagnostic inaccuracies. While many programs have been initiated to address the system-related factors such as improved communication, enhancing the concept of an effective teamwork, and tackling the procedural problems, clear pathways to reduce the diagnostic errors contributed by the cognitive factors have been more elusive and indefinable. A wide range of suggestions have been made about how to reduce cognitive errors in making the correct diagnosis. Graber et al[6] have described three distinct categories of interventions as those meant to: (1) improve knowledge and experience; (2) improve clinical reasoning and decision-making skills; and (3) provide cognitive “help”. Though many of these suggestions are well conceptualized and widely endorsed, a large portion remain untested or testing has been restricted to trainees in artificial settings, which does not necessarily reflect actual practice[7]. The diagnostic pathway for acute surgical patients involves GPs, Accident and Emergency, and surgeons. The need to investigate and quantify the impact of procedural and diagnostic accuracy at each level of medical contact is clear. Lack of a working diagnosis impacts patient care, outcome, and cost.

The objective of this observational study is to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy at each level of the primary diagnostic pathway in acute surgical patients admitted to a District General Hospital.

It was noted that ward rounds for on-call surgeons were often disorganized, with no clear roles defined, leading to inconsistent record keeping. Therefore, on call surgical team decided to address this by running ward rounds using briefing and debriefing for each ward round, rotating roles (each person present taking turns with patient presentation, record-keeping, and drug chart review), and asking each member of the team if they had anything to add before moving to the next patient. The surgical team was encouraged to clearly record 3 differential diagnoses for each doctor-patient encounter. It became apparent that the differential diagnoses listed would often change along the primary diagnostic pathway, and the idea to survey these changes emerged.

A one-page profroma was designed and relevant variables reported in previous but similar publications were inserted on it. Because this was an observational and pilot study examining the performance of the acute surgical team without any involvement of the patients, therefore, only an informal approval of the study was taken from the local Ethics and Research Committee with verbal discussion and electronic communication. The contents of the profroma were presented in internal clinical governance meeting and few additional variables were also included based upon the recommendations of clinical governance panel. All authors and local Ethics and Research Committee approved the profroma and its contents before starting the data collection.

To review the case notes and ward round entries of all acute surgical admissions during randomly selected two weeks.

Patients whose notes were not available through secretaries or on the wards during data collection were excluded.

Patient information including surname, hospital number, date of birth, and gender was collected onto a one page proforma, and each doctor/patient encounter was reviewed retrospectively to include up to 3 differential diagnoses listed in the patient notes. Doctors were anonymously recorded as general practitioner (GP), accident and emergency doctor (A and E), in-patient referrer (IP), surgical foundation year-1, surgical senior house officer (SHO), surgical registrar on-call (SROC), and the surgical consultant. Patient/doctor encounters were recorded along the primary diagnostic pathway, from GP referral, if available, up to the first surgical consultant review or definitive diagnosis by emergency surgery if that preceded consultant review. Final diagnosis was determined by surgical findings, radiological confirmation, or clinical consensus of the rounding on call surgical team comprised of surgical F1, surgical SHO, SROC and surgical consultant as recorded in the discharge summary. All data was kept together in a ring binder and later entered into a spreadsheet for analysis. Authors collected data independently and later on the discrepancies were removed with mutual discussions. There was high and statistically satisfactory inter-observer agreement based upon the Kappa Statistic Score of 0.93.

Data was organized and analyzed using Microsoft Excel® spread sheet (Office 2010, Microsoft Corporation, New York, United States). Statistical analysis was performed with Review Manager 5.2. Each differential diagnosis listed in a doctor/patient encounter was compared to the final diagnosis and scored as correct or incorrect. Failure to list any differential diagnosis was regarded as incorrect.

Recording a differential diagnosis that corresponded with the discharge summary was accepted as an accurate diagnosis.

Forty-one patients (23 males) with mean age of 61.05 (± 23.24) years were evaluated over 111 patient-doctor encounters. Surgery or other invasive diagnostic procedure was performed in 48.8% of patients. Correct diagnosis was achieved in 85.4% of patients along the primary diagnostic pathway.

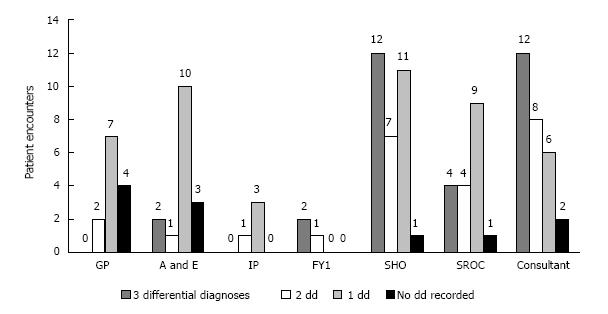

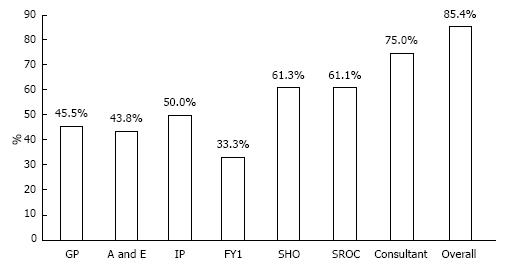

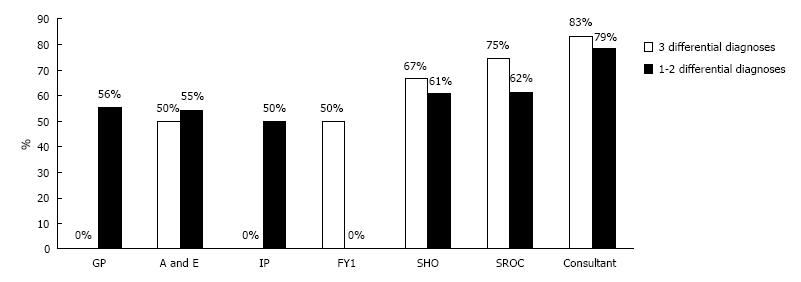

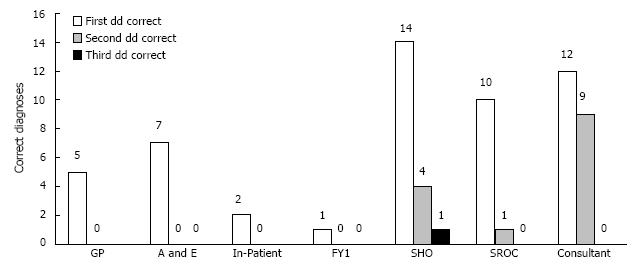

As shown in Figure 1, FY1, Consultant, and SHO recorded 3 differential diagnoses most often, (67%, 43%, and 39%, respectively) while referring physicians rarely recorded 3 differentials, i.e., 0%, 12.5%, and 0% for GP, A/E, and IP respectively. Consultant was most likely to record a correct diagnosis (75%), followed by SHO (61.3%) and SROC (61.1%) (Figure 2). The accuracy of encounters with 3 differentials listed was 68.75% vs 63.77% for just 1-2 differentials. Among the surgical team, the use of 3 differential diagnoses did improve diagnostic accuracy by 8.1%, (65.2% to 73.3%) though significance was not reached (Figure 3). Three differentials were listed at least one time in 23 of the 41 patients. A correct diagnosis was made in 19 of these patients (82.6%). In the remaining 18 patients only 1-2 differentials were ever listed. A correct diagnosis was made in 16 of these patients (88.9%). Of the 32 times in which 3 differentials were listed, only one (3.1%) of these had the correct diagnosis as the third differential (Figure 4).

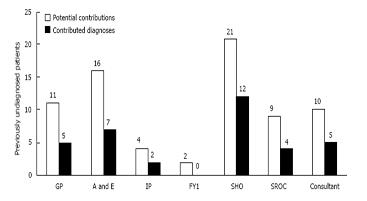

It is important to identify where diagnoses were made, rather than simply repeated from a previous clinician. If a correct diagnosis had not been made previously, the clinician had the potential to contribute a correct diagnosis. As shown in Figure 5, the surgical SHO contributed the correct diagnoses most often (57.1% of potential contributions). The surgical SHO also contributed 34.3% of all correct diagnoses, the highest of any surgical personnel on call. Three differentials were used to make contributions most often by SHO, followed by Consultant and then by the SROC (66.7%, 60%, and 50% respectively).

Failure to include a correct diagnosis made by a previous clinician was regarded as a right-to-wrong change. This occurred 5 times in 111 (4.5%), however 4 of these cases were due to no diagnosis being recorded after a correct diagnosis had been made previously. Only one truly right-to-wrong diagnosis was made, (0.9%) in which malignancy was removed from the list of differentials.

Patients referred by a GP were more than twice as likely to undergo surgery as patients referred from A/E. (OR 4.40, CI: 1.09-17.72, P = 0.04) However, due to the small size of this study, significance was not reached for GP vs in-patient referrals (P = 0.15) (Figure 6).

Approximately 85% of acute surgical patients can be diagnosed accurately along the primary diagnostic pathway during acute presentations. The surgical consultant was more likely to make a correct surgical diagnosis compared to all health personnel; however it is the surgical SHO that contributes the most correct diagnoses along the diagnostic pathway. Patients referred by a GP are more likely to require surgery as compared to other referral sources.

Premature closure, the cognitive error of failing to continue to consider reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis has been made, is often cited as the most common cognitive factor leading to a diagnostic error[7-11]. Much of the focus on decreasing cognitive errors has been on improving clinical reasoning and decision-making by educating physicians about how they make decisions and teaching the use of de-biasing techniques and active meta-cognitive review[12]. Some difficulties with the implementation of these strategies include time, cost, and physician interest, as well as the need to prove the efficacy of these strategies in clinical practice[13]. The potential to reduce the incidence of premature closure with a simple practice that would require no further training and could be easily tested in clinical practice would be ideal as a means to reduce dangerous and costly diagnostic errors. The authors suggest that the practice of clearly listing 3 differential diagnoses in the patient notes is a simple way to modestly decrease the cognitive error of premature closure. Listing of three differentials vs listing of one or two differentials seems to improve the diagnostic accuracy among the surgical team, although a larger study would be needed to reach statistical significance. For the 8.1% improvement in diagnostic accuracy seen among the surgical team to be statistically significant (95%CI, 80% power), over 547 patient records should be evaluated. Further support for the use of three differentials comes from the increased proportion of diagnoses contributed using this method. Given the impact of misdiagnosis on the healthcare system, the difficult nature of reducing cognitive errors in clinical practice, and the simplicity of the intervention described, the authors feel it is worthwhile to consider further study in this area to explore any benefit of this practice.

The small size of this study limits the statistical significance of many of the trends seen in the data. Other limitations noted during the data collection included difficulty in locating GP referral letters in the patient notes and therefore not including those encounters, as well as missing patients that were seen by on-call surgeons in the evening and subsequently discharged before morning rounds. The use of a junior doctor scribe when patients are reviewed by a consultant or registrar may result in differential diagnoses being stated but not recorded, and therefore not counted.

One of the strategies to reduce diagnostic error is to develop pathways for feedback[2,14]. It is particularly important to develop feedback pathways for the junior doctors, as it has been shown that less experienced doctors tend to most over-estimate their diagnostic accuracy[2]. With anonymity removed, the basic design of this study seems well suited to enable feedback to each physician involved in the care of an acute surgical patient. In this way a simple score could be reported as a way to objectively evaluate diagnostic performance, with the ultimate goal of self-improvement and future decrease in diagnostic errors. This approach would allow feedback not just after a negative event, as is the case with many feedback systems in place, but would track performance in a simple, ongoing manner.

Accurate clinical diagnosis in acutely admitted surgical patients is of immense importance because of the necessity of timely surgical interventions such as need of laparotomy, laparoscopy and or organ resection. Inaccurate diagnosis can lead to serious consequences in terms of delayed treatment, prolonged hospital stay, increased operative morbidity or mortality putting excessive strain on the health resources. Any measure which directly or indirectly may influence the diagnostic accuracy in acute surgical patients should be investigated and implemented in a timely manner to avoid these consequences. This article highlights the value and shortcomings of a referral pathway through which acute surgical patients pass through and get accurately diagnosed for the optimum management.

Various studies published on this topic, although reported the diagnostic accuracy of different grades of acute surgical team with variable accuracy. This is the first study which investigates the diagnostic accuracy of all sources of referral during the course of management of acutely ill patients such as general practitioners, A/E doctors, surgical juniors, surgical middle grade doctors and eventually surgical consultant on call.

The potential to reduce the incidence of mis-diagnosis with a simple practice that would require no further training and could be easily tested in clinical practice would be ideal as a means to reduce dangerous and costly diagnostic errors. The authors suggest that the practice of clearly listing 3 differential diagnoses in the patient notes is a simple way to modestly decrease the cognitive error of premature closure. Listing of three differentials vs listing of one or two differentials seems to improve the diagnostic accuracy among the surgical team, although a larger study would be needed to reach statistical significance. For the 8.1% improvement in diagnostic accuracy seen among the surgical team to be statistically significant (95%CI, 80% power), over 547 patient records should be evaluated. Further support for the use of three differentials comes from the increased proportion of diagnoses contributed using this method. Given the impact of misdiagnosis on the healthcare system, the difficult nature of reducing cognitive errors in clinical practice, and the simplicity of the intervention described, the authors feel it is worthwhile to consider further study in this area to explore any benefit of this practice.

One of the strategies to reduce diagnostic error is to develop pathways for feedback. It is particularly important to develop feedback pathways for the junior doctors, as it has been shown that less experienced doctors tend to most over-estimate their diagnostic accuracy. With anonymity removed, the basic design of this study seems well suited to enable feedback to each physician involved in the care of an acute surgical patient. In this way a simple score could be reported as a way to objectively evaluate diagnostic performance, with the ultimate goal of self-improvement and future decrease in diagnostic errors. This approach would allow feedback not just after a negative event, as is the case with many feedback systems in place, but would track performance in a simple, ongoing manner.

FY1: It stands for foundation year 1. The group of junior most surgical doctors in the United Kingdom NHS Trust health system which start clinical practice just after finishing medical school. SHO: It stands for Senior House Officer which a surgical grade after finishing two years of foundation training (FY1 and FY2). SROC: Its stands for Surgical Registrar On Call. Surgical registrar is of variable experience depending upon the step of ladder on training pathway (year 1 to year 8).

This is an interesting article.

| 1. | Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, Shore A, Makary MA, Pronovost PJ, Newman-Toker DE. 25-Year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:672-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med. 2008;121:S2-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 582] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nuland S. How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter. New York, NY: Knopf 1994; 248. |

| 4. | Graber ML, Wachter RM, Cassel CK. Bringing diagnosis into the quality and safety equations. JAMA. 2012;308:1211-1212. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Berner ES, Miller RA, Graber ML. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:470; author reply 470-471. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1493-1499. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Graber ML, Kissam S, Payne VL, Meyer AN, Sorensen A, Lenfestey N, Tant E, Henriksen K, Labresh K, Singh H. Cognitive interventions to reduce diagnostic error: a narrative review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:535-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Acad Med. 2011;86:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vázquez-Costa M, Costa-Alcaraz AM. Premature diagnostic closure: an avoidable type of error. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2013;213:158-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eva KW, Link CL, Lutfey KE, McKinlay JB. Swapping horses midstream: factors related to physicians’ changing their minds about a diagnosis. Acad Med. 2010;85:1112-1117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Borrell-Carrió F, Epstein RM. Preventing errors in clinical practice: a call for self-awareness. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:310-316. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775-780. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nendaz M, Perrier A. Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning: mechanisms and prevention in practice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anderson RE, Graber ML. The new kid on the patient safety block: Diagnostic Error in Medicine. NPSF Professional Learning Series. Available from: http://www.npsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/PLS_1111_RE.pdf. |

P- Reviewer: Bludovsky D, Buell JF, Paraskevas KI S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ