Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114050

Revised: September 30, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 133 Days and 6.2 Hours

Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma (HEAML) is rare subtype of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor that is typically benign but has malignant potential. Mis

This article presents a case of multifocal HEAML in a 37-year-old woman. Five years prior, abdominal ultrasound incidentally detected two hyperechoic lesions in the liver, which were initially diagnosed as hemangiomas and managed with routine imaging surveillance. At a recent follow-up, the progressive enlargement of both lesions was noted, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography raised the possibility of AML. The patient had a laparoscopic procedure to remove the tumor in the left liver lobe after the lesion progressed. Postoperative histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of HEAML. Transarterial embolization was chosen as an alternative to surgical resection because of the high operative risk associated with the proximity of the right lobe lesion to the hepatic hilum. The patient had an uneventful recovery, and no recurrence was detected at follow-up.

Surgical resection combined with interventional embolization has proven effective for managing multifocal HEAML, a rare tumor with a high risk of misdiagnosis.

Core Tip: We report a case of multifocal hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma successfully managed with a multimodal approach combining laparoscopic resection and transarterial embolization. The predominant left lobe lesion was resected, while the high-risk hilar lesion was treated with minimally invasive transarterial embolization, interrupting arterial supply to achieve tumor control and preserve hepatic function. Follow-up showed uneventful recovery without recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report highlighting the feasibility and therapeutic benefit of this combined strategy, providing a paradigm for the individualized management of multifocal hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma.

- Citation: Wang F, Shi ZX, He XY, Han XJ, Wang JH, Yang JY, Cui LM. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma treated with laparoscopic resection and transcatheter arterial embolization first time: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 114050

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/114050.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.114050

Angiomyolipoma (AML) is a rare, benign mesenchymal tumor that can present with unexpectedly aggressive clinical features[1]. It belongs to the perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) family, a group of neoplasms derived from PECs[2,3]. Hepatic epithelioid AML (HEAML) comprises varying amounts of smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue, and blood vessels, with the smooth muscle component being the key feature for diagnosis[4]. HEAML shows a marked female predominance, with a reported female-to-male ratio of approximately 5:1. Lesions are typically solitary and are most commonly located in the right lobe of the liver[5,6]. Due to their indolent and asymptomatic nature, HEAMLs are frequently discovered incidentally. The disease is generally asymptomatic and presents with nonspecific imaging features, which complicates accurate clinical diagnosis. This report describes a case of HEAML with the objective of increasing clinical recognition of this rare tumor, minimizing the risk of misdiagnosis, and proposing a potential therapeutic strategy.

A 37-year-old woman presented with two hepatic lesions, which were first identified 5 years prior.

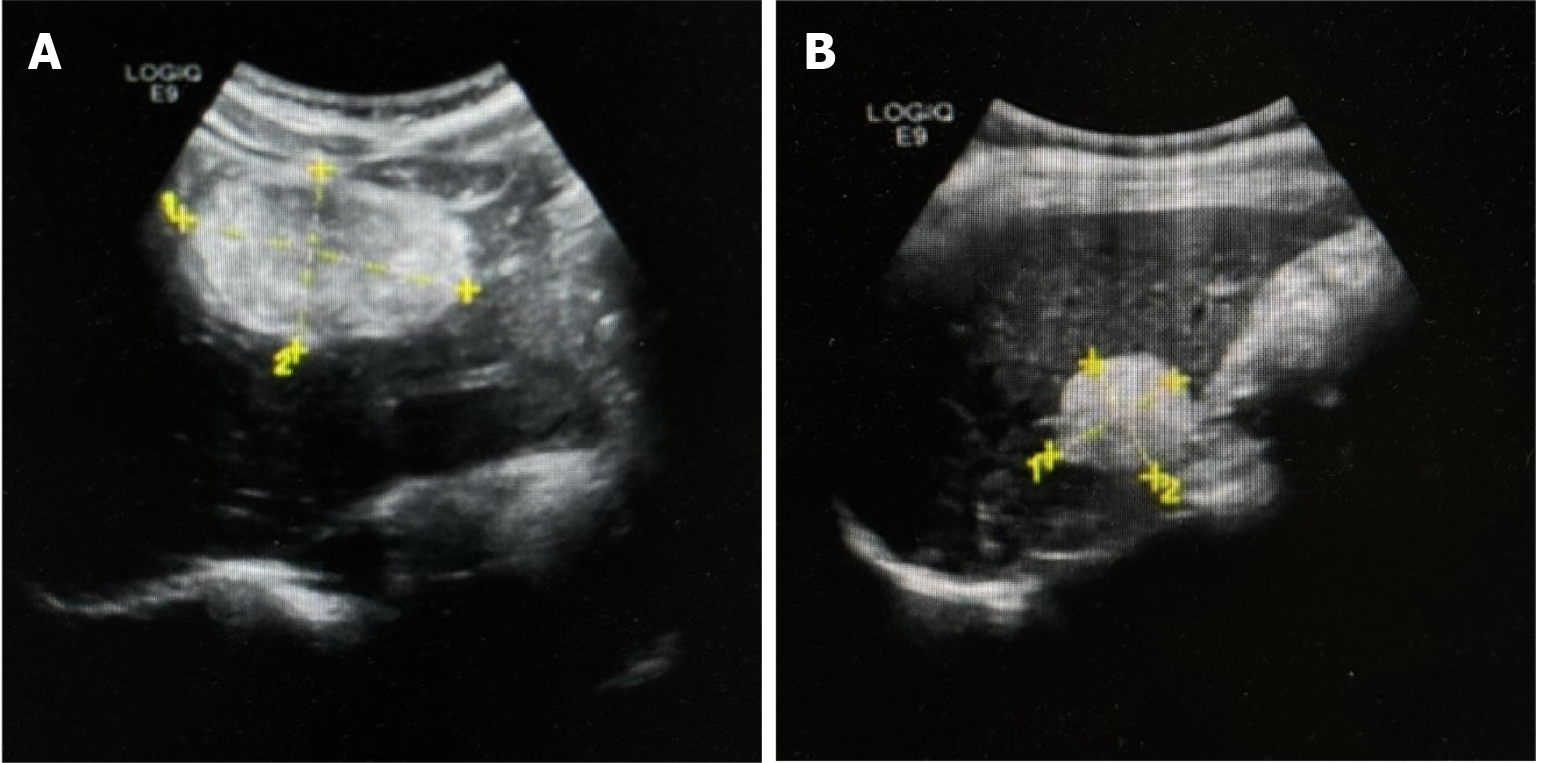

Five years prior, a well-defined, slightly hyperechoic lesion measuring approximately 23 mm × 15 mm was discovered via abdominal ultrasound in segment S3 of the left lateral hepatic lobe. An additional lesion, measuring approximately 48 mm × 44 mm, was detected in the anterior segment of the right hepatic lobe. These findings were considered consistent with hepatic hemangiomas, and routine imaging follow-up was recommended. A follow-up ultrasound performed 3 months prior at a local hospital identified two hyperechoic lesions in the liver parenchyma, measuring 55 mm × 38 mm and 29 mm × 31 mm, respectively. Both lesions remained well-circumscribed, and hepatic hemangioma was again considered likely; continuing imaging surveillance was advised. Due to progressive enlargement of the lesions on serial imaging, the patient presented to our hospital for further evaluation and management.

The patient denied any specific personal past medical history. She denied alcohol or tobacco abuse.

No hereditary diseases, history of allergies, nor epidemiologic linkage were described.

The patient’s vital signs were stable and within normal physiological ranges. Cardiopulmonary examination revealed no remarkable abnormalities. The abdomen was flat and non-tender, with no rebound tenderness or muscle rigidity. No abdominal wall varices were noted. Hepatic dullness was preserved, and there was no tenderness with percussion. Shifting dullness was absent, and the liver and spleen were not enlarged.

Laboratory evaluations revealed normal hepatic and renal function, with electrolyte levels and coagulation profiles within reference ranges. Serologic tests showed no evidence of hepatitis or other infectious diseases.

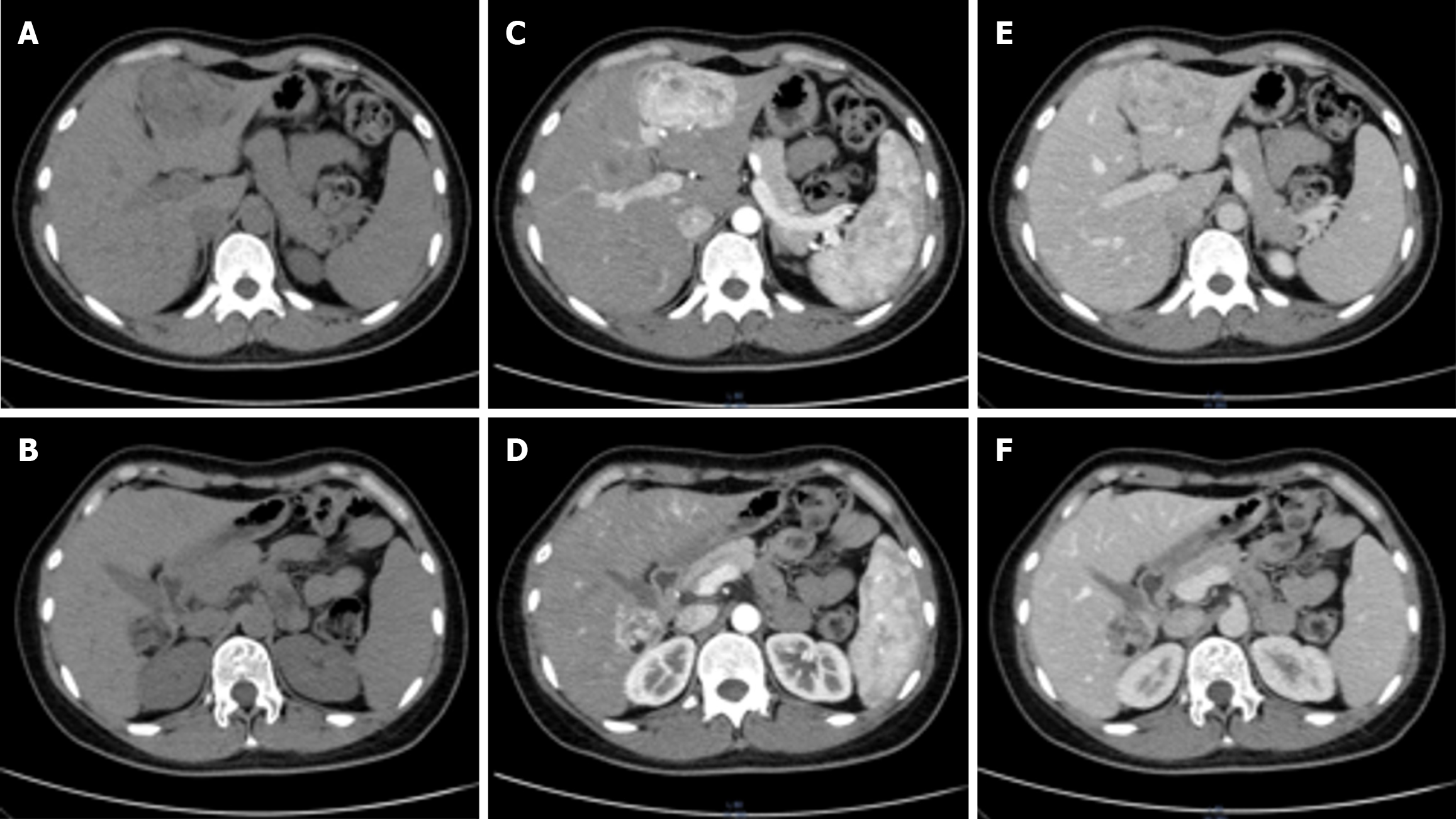

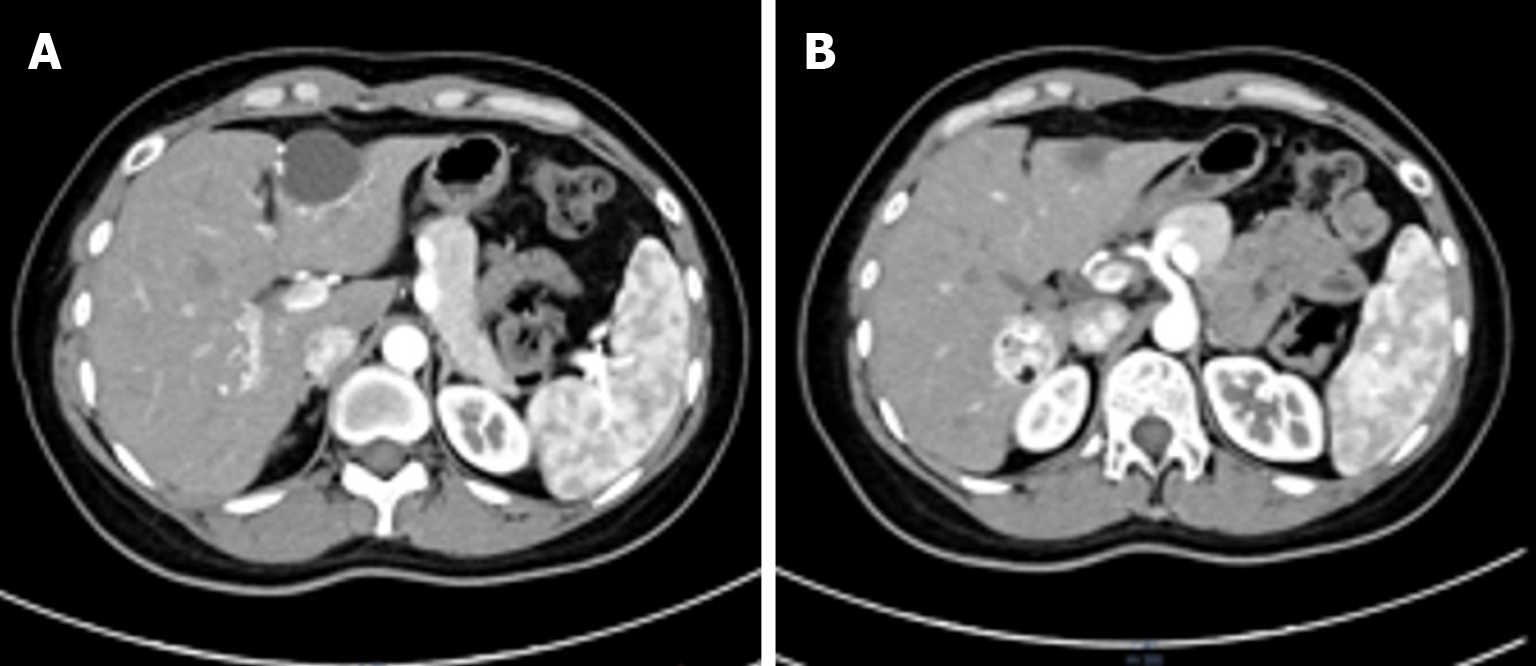

Ultrasound demonstrated a slightly hyperechoic lesion measuring approximately 71 mm × 49 mm in the left hepatic lobe and an additional lesion of approximately 33 mm × 32 mm in the right lobe, both with sharply defined margins. These sonogram findings were consistent with hepatic hemangiomas (Figure 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen revealed mass lesions in hepatic segments S3 and S7, with the larger one in the left lobe measuring approximately 61 mm × 44 mm and showing heterogeneous density. In the arterial phase, the lesion exhibited pronounced heterogeneous enhancement, with visible intratumoral vasculature and adjacent vessel dilation. The lesion became isodense during the portal venous and delayed phases. These radiologic findings were consistent with a possible diagnosis of AML (Figure 2).

Given the patient’s clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and imaging results, there was insufficient evidence to establish a definitive diagnosis of AML, and the preoperative diagnosis remained inconclusive. Consequently, post

HEAML is a rare mesenchymal tumor that, while generally considered benign, possesses malignant potential[1], necessitating surgical management. Following informed consent from the patient and her family, a laparoscopic partial hepatectomy was performed. Intraoperatively, the round and falciform ligaments were divided with an ultrasonic scalpel. The hepatoduodenal ligament was carefully dissected, and a vascular occlusion tape was positioned. The segment III hepatic lesion was excised with a 3 cm margin beyond its visible boundary. Intrahepatic ducts and vessels were ligated and transected with Hem-o-locks and titanium clips; peripheral ducts near the lesion were divided using a linear stapling device. Following complete resection of the left hepatic lobe tumor, bipolar electrocoagulation was used to achieve hemostasis along the hepatic transection plane. The patient tolerated the procedure well, with no intraoperative nor postoperative complications reported. Due to the proximity of the right hepatic lesion to the hepatic hilum and the elevated risk of hemorrhage, the caudate lobe lesion was left untreated. The resected hepatic tissue from the left lobe was sent for histopathological examination.

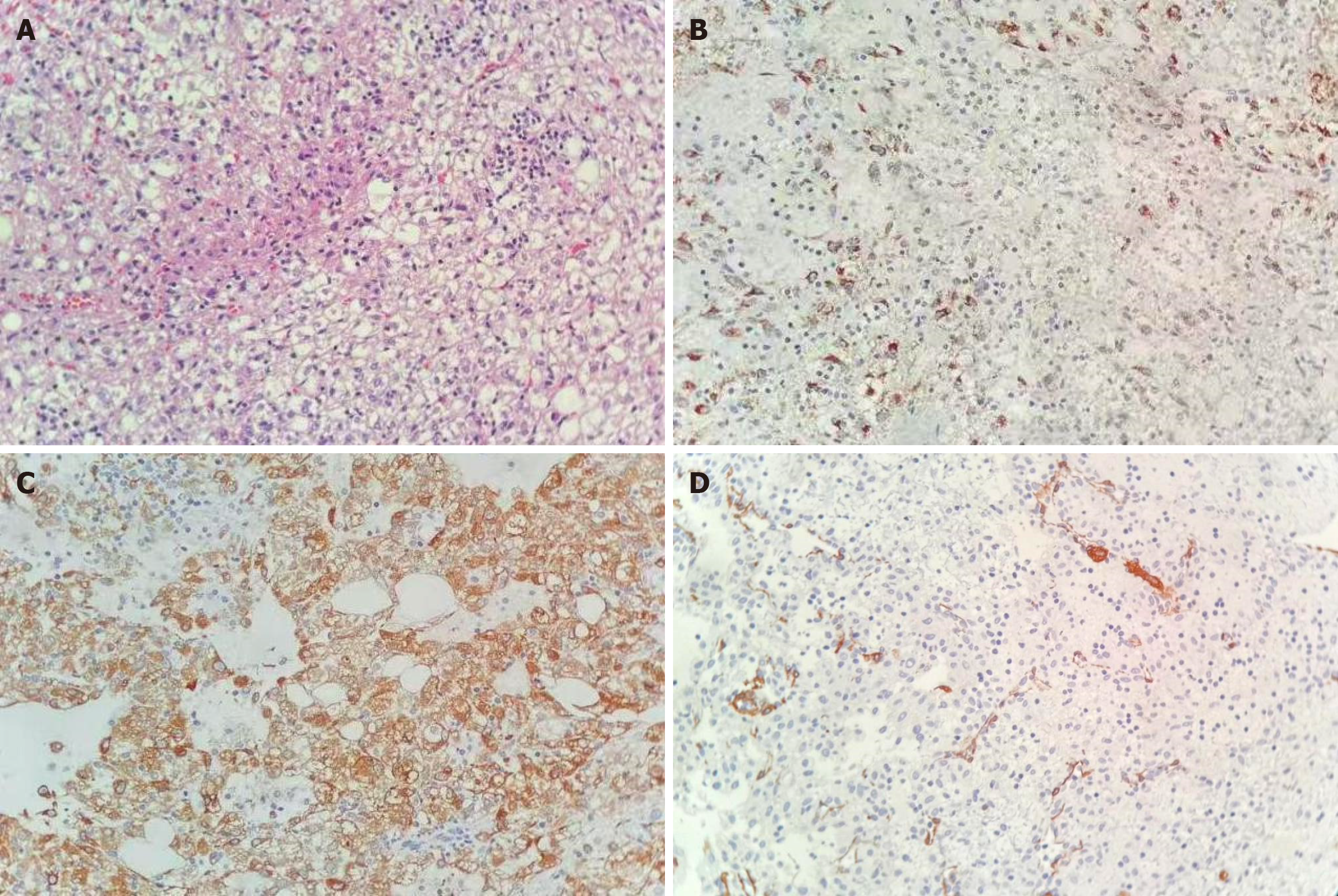

Gross examination of the resected liver specimen revealed a dark reddish-purple appearance; the cut surface had a soft texture and a mixed coloring of gray, red, and yellow. Histopathological analysis showed sheets of epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and round nuclei. Some of these cells contained a pale, vacuolated cytoplasm. Thick-walled blood vessels were concentrically arranged around the epithelioid cells. A small amount of mature adipose tissue was also identified. Immunohistochemical staining revealed strong positive staining for smooth muscle actin, human melanoma black (HMB-45), and melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (Melan-A), with negative results for cytokeratin 8/18, desmin, and S-100. CD34 immunoreactivity was detected in vascular endothelial cells, while the Ki-67 proliferation index was low, at approximately 2%. Based on these histopathological and immunohistochemical findings, a definitive diagnosis of HEAML was established (Figure 3).

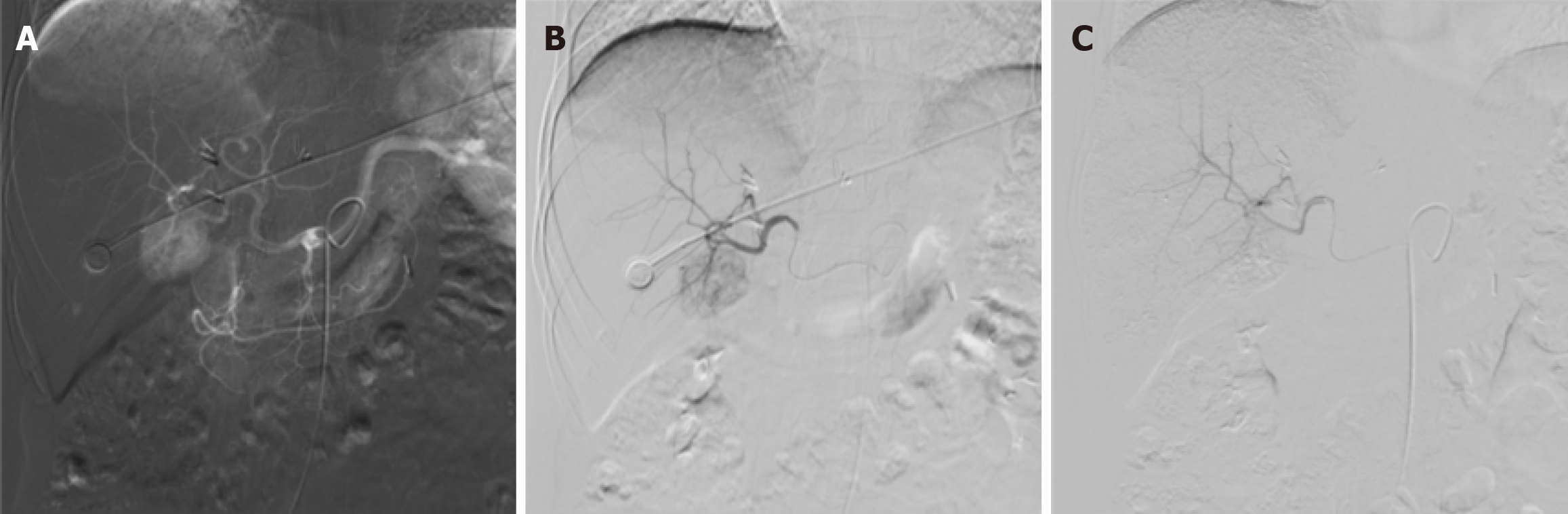

Following a multidisciplinary team discussion, transarterial embolization (TAE) was selected as the treatment strategy for the HEAML located in the right lobe. Under local infiltration anesthesia with 2% lidocaine, the right femoral artery was accessed using the Seldinger technique, and a standard arterial sheath was introduced. Angiography of the superior mesenteric artery and celiac trunk was performed using a 5F RH catheter, revealing satisfactory portal venous return but significant tumor vascularity and staining in the liver parenchyma. A microcatheter was advanced to achieve superselective catheterization of the tumor-feeding artery, through which 8 mL of lipiodol was administered. Post-embolization angiography demonstrated complete resolution of tumor staining, indicating successful embolization of the tumor vasculature (Figure 4). The patient tolerated the procedure well, with no intraoperative or postoperative discomfort or complications observed.

The patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful, with all routine laboratory parameters remaining within normal limits. Follow-up assessments indicated that the patient was asymptomatic and maintained good overall health. Contrast-enhanced CT performed 3 months postoperatively demonstrated partial resection of the left hepatic lobe, with a localized cystic hypodense area at the site of resection. The right hepatic lesion treated with TAE had decreased in size from 33 mm to 27 mm. No radiological signs of recurrence nor other abnormalities were detected (Figure 5).

PEComas are a group of mesenchymal neoplasms with malignant potential, characterized by the co-expression of melanocytic and smooth muscle markers[1]. AML is the most common benign renal tumor, but its occurrence in the liver is rare, representing only about 0.4% of all primary hepatic tumors[7,8]. Since 1976, when hepatic AML was initially described by Ishak[9], the majority of cases have been found to occur in women and to be asymptomatic, typically arising in non-inflammatory livers with no associated serologic abnormalities. As such, hepatic AMLs are frequently detected incidentally, and their underlying pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Although more than 50% of renal AMLs are associated with tuberous sclerosis complex, only 5% to 15% of isolated hepatic AMLs exhibit this correlation.

Historically, HEAML has been regarded as a benign lesion. Accumulating evidence, however, has indicated a non-negligible potential for malignancy, a factor that directly influences both the long-term prognosis of the patient and the selection of therapeutic strategies by the clinical care team. In alignment with individual case reports[10,11], a recent systematic review has provided the most comprehensive data to date supporting this notion[12]. Upon that analysis of 75 articles encompassing a total of 224 patients, a postoperative recurrence rate of 3.1% and a distant metastasis rate of 2.7% was found. Although these percentages are modest, they offer clear evidence of the aggressive potential of HEAML.

Regarding imaging, conventional ultrasound is the first-line screening tool for focal liver lesions. For the present case, the tumor had exhibited heterogeneous hyperechogenicity, a finding consistent with lesions rich in fat or smooth muscle. This appearance’s close resemblance to that of the more common hepatic hemangioma led to repeated initial misdiagnoses[13,14]. This unfortunate complication highlights an important fact that can benefit the future care of HEAML cases, namely while conventional ultrasound remains valuable for screening, its low specificity poses a primary obstacle in definitive diagnosis. Consequently, further evaluation with CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required. On non-contrast CT, the lesion typically appears as a low-density mass, which may be homogeneous or heterogeneous, with well-defined or ill-defined borders. The tumor is composed of soft-tissue components, including smooth muscle and vascular structures. Due to its hypervascular nature, the lesion shows marked enhancement in the arterial phase, followed by washout or iso-density in the portal venous and delayed phases[15]. Since CT is often insensitive for detection of small amounts of fat, MRI (particularly with chemical shift imaging) is the gold standard for detecting intratumoral fat. Nevertheless, the variable fat content in AML often complicates diagnostic interpretation. HEAML typically appears on MRI as hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense or heterogeneous on T2-weighted images, showing high signal on diffusion-weighted imaging. Post-contrast scans demonstrate avid arterial phase enhancement with subsequent washout in the portal venous and delayed phases[16]. The presence of rich vasculature and arteriovenous shunting on contrast-enhanced CT or MRI can aid in the diagnosis of a PEComa[17,18].

Although CT and MRI significantly improve diagnostic accuracy for HEAML, the imaging features often overlap with those of other malignant tumors, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[19]. This makes a definitive diagnosis based on imaging alone challenging. Advanced techniques like contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) serve as an important adjunct by providing unique information on microvascular circulation. On CEUS, AML typically shows marked arterial phase hyperenhancement followed by washout in the portal and late phases. The early enhancement and rapid venous drainage observed on CEUS are suggestive of a PEComa[20]. For hepatic AML, CEUS holds a significant diagnostic advantage over conventional ultrasound, reportedly increasing the detection rate from 24% to 52%[21].

The variable imaging appearance of the PEComa family of tumors is a result of their complex histology, which includes adipose tissue, smooth muscle, vascular structures, and epithelioid cells, coupled with their radiological similarity to hypervascular hepatic tumors such as HCC. This significant heterogeneity is a major contributing factor to diagnostic difficulty, with preoperative accuracy rates reportedly as low as 25% to 52%[22,23]. Therefore, establishing clear in

Histopathological assessment plays a pivotal role in the definitive diagnosis of PEComa. These tumors are characterized histologically by the presence of PECs and by immunoreactivity for melanocytic and smooth muscle markers, including HMB-45 and smooth muscle actin. HEAML, a variant within the PEComa family, typically expresses melanocytic markers such as HMB-45 and Melan-A. Negative S-100 staining is useful in distinguishing HEAML from malignant melanoma[26]. Therefore, the combination of epithelioid morphology, HMB-45 and Melan-A positivity, and S-100 negativity supports the qualitative diagnosis of HEAML[27]. Nonetheless, studies have indicated that up to 30% of patients may lack a definitive diagnosis despite undergoing biopsy, underscoring the need for heightened clinical and pathological awareness[12].

Surgical resection remains the standard curative treatment for HEAML, offering high success rates in most reported cases. Both open and laparoscopic partial hepatectomies are effective surgical strategies[28-31]. For patients ineligible for surgery, some researchers propose ablation or interventional therapies as potential alternatives following biopsy confirmation, although the therapeutic efficacy of these approaches remains uncertain[32,33]. Review of the existing literature revealed a few exceptional cases in which ruptured HEAMLs presenting with massive hemorrhage were initially stabilized with hepatic artery embolization, followed by definitive laparoscopic resection[34,35]. A 2023 case study described a patient who was initially misdiagnosed with HCC and, because of multiple lesions, was not a can

In our case, a combined strategy involving laparoscopic partial hepatectomy and TAE was employed to manage multifocal HEAML. This dual approach, which involved complete resection of the dominant lesion and selective embolization of the smaller lesions, provides several advantages including maximal preservation of healthy liver tissue to maintain function, reduced intraoperative bleeding risk, and improved feasibility of repeated interventions for residual or recurrent disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case to utilize a combination of laparoscopic resection and embolization for the management of hepatic AML. Further research is warranted to assess the therapeutic efficacy of this combined modality in multifocal HEAML and to explore optimal TACE agents and neoadjuvant strategies for hepatic AML.

It is important to acknowledge and consider the potential limitations of this study. First, as a case report, our findings cannot be used to establish treatment guidelines for other cases of multiple HEAML, and the generalizability of the surgical approach used in this single case is limited. Additionally, the patient's refusal of further examinations and treatment resulted in a lack of long-term follow-up, which restricts our ability to assess the therapeutic efficacy of TAE for HEAML. Finally, this case lacked molecular profiling of the tumor (e.g., TSC1/TSC2 mutation analysis) and genetic analysis to rule out associated syndromes like tuberous sclerosis complex. This ultimately prevented our deeper exploration of the underlying biological characteristics of HEAML.

In our future work, we plan to collect a larger cohort of HEAML cases and initiate multicenter studies to validate the efficacy of combining resection with embolization. We also aim to conduct prospective studies comparing various treatment modalities, including TAE, TACE, ablation, and systemic mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (e.g., sirolimus). Furthermore, establishing multicenter collaborations to create a dedicated biobank is necessary to explore the genetic features of HEAML. Such efforts will facilitate risk stratification and help identify potential targets for systemic therapy. We anticipate that these future investigations will deepen the collective understanding of HEAML.

Herein, we have reported a rare case of multiple HEAML and, to our knowledge, are the first to document the complete course of successful treatment using a combination of laparoscopic hepatectomy and interventional embolization. For this rare tumor, which is challenging to diagnose and lacks standardized guidelines, this hybrid strategy offers a novel paradigm for safe and effective individualized therapy by targeting the primary lesion for resection while managing high-surgical-risk lesions with minimally invasive embolization. While this case offers a valuable clinical reference, its inherent limitations - notably, the lack of generalizability common to single-case reports and the absence of long-term follow-up data - must be acknowledged. Future research should focus on larger, multicenter studies to validate the long-term efficacy of this hybrid strategy. The ultimate goal is to establish standardized treatment guidelines for multiple HEAML and thereby improve patient outcomes.

| 1. | Tsui WM, Colombari R, Portmann BC, Bonetti F, Thung SN, Ferrell LD, Nakanuma Y, Snover DC, Bioulac-Sage P, Dhillon AP. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:34-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2769] [Article Influence: 461.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Bonetti F, Pen M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Manirin E, Colombari R, Mariuzzi GM. The Perivascular Epithelioid Cell and Related Lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 1997;4:343-358. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Talati H, Radhi J, Popovich S, Marcaccio M. Hepatic Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma: Case Series. Gastroenterology Res. 2010;3:293-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SY, Kim BH. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the liver: a case report. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:91-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu W, Meng Z, Liu H, Li W, Wu Q, Zhang X, E C. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma is a rare and potentially severe but treatable tumor: A report of three cases and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3669-3675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sun H, Yang M. An Unusual Variant of Hepatic Inflammatory Angiomyolipoma: Report of a Rare Entity. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46:78-82. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Jung DH, Hwang S, Hong SM, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Alshahrani AA, Lee SG. Clinico-pathological correlation of hepatic angiomyolipoma: a series of 23 resection cases. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E60-E65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ishak KG. Primary hepatic tumors in childhood. Prog Liver Dis. 1976;5:636-667. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wu C, Yang Y, Tian F, Xu Y, Qu Q. A rare case of giant hepatic angiomyolipoma with subcapsular rupture. Front Surg. 2023;10:1164613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fukuda Y, Omiya H, Takami K, Mori K, Kodama Y, Mano M, Nomura Y, Akiba J, Yano H, Nakashima O, Ogawara M, Mita E, Nakamori S, Sekimoto M. Malignant hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma with recurrence in the lung 7 years after hepatectomy: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kvietkauskas M, Samuolyte A, Rackauskas R, Luksaite-Lukste R, Karaliute G, Maskoliunaite V, Valkiuniene RB, Sokolovas V, Strupas K. Primary Liver Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor (PEComa): Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hoffman AL, Emre S, Verham RP, Petrovic LM, Eguchi S, Silverman JL, Geller SA, Schwartz ME, Miller CM, Makowka L. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: two case reports of caudate-based lesions and review of the literature. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:46-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Prasad SR, Wang H, Rosas H, Menias CO, Narra VR, Middleton WD, Heiken JP. Fat-containing lesions of the liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25:321-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tan Y, Xie X, Lin Y, Huang T, Huang G. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: clinical features and imaging findings of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and CT. Clin Radiol. 2017;72:339.e1-339.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu W, Wang J, Huang Q, Lu Q, Liang W. Comparison of MRI Features of Epithelioid Hepatic Angiomyolipoma and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Imaging Data From Two Centers. Front Oncol. 2018;8:600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shen HQ, Chen DF, Sun XH, Li X, Xu J, Hu XB, Li MQ, Wu T, Zhang RY, Li KZ. MRI diagnosis of perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the liver. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54:643-647. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Parfitt JR, Bella AJ, Izawa JI, Wehrli BM. Malignant neoplasm of perivascular epithelioid cells of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1219-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Son HJ, Kang DW, Kim JH, Han HY, Lee MK. Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): a case report with a review of literatures. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Akitake R, Kimura H, Sekoguchi S, Nakamura H, Seno H, Chiba T, Fujimoto S. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the liver diagnosed by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Intern Med. 2009;48:2083-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang B, Ye Z, Chen Y, Zhao Q, Huang M, Chen F, Li Y, Jiang T. Hepatic angiomyolipomas: ultrasonic characteristics of 25 patients from a single center. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:393-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chang Z, Zhang JM, Ying JQ, Ge YP. Characteristics and treatment strategy of hepatic angiomyolipoma: a series of 94 patients collected from four institutions. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ji JS, Lu CY, Wang ZF, Xu M, Song JJ. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma of the liver: CT and MRI features. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Junhao L, Hongxia Z, Jiajun G, Ahmad I, Shanshan G, Jianke L, Lingli C, Yuan J, Mengsu Z, Mingliang W. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2023;48:913-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Maebayashi T, Abe K, Aizawa T, Sakaguchi M, Ishibashi N, Abe O, Takayama T, Nakayama H, Matsuoka S, Nirei K, Nakamura H, Ogawa M, Sugitani M. Improving recognition of hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5432-5441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ronen S, Prieto VG, Aung PP. Epithelioid angiomyolipoma mimicking metastatic melanoma in a liver tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:824-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Xu H, Wang H, Zhang X, Li G. [Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 25 cases]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2014;43:685-689. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Wang ZS, Xu L, Ma L, Song MQ, Wu LQ, Zhou X. Hepatic falciform ligament clear cell myomelanocytic tumor: A case report and a comprehensive review of the literature on perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Feng JW, Liu CW, Yang XH, Jiang Y, Qu Z. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11:1739-1745. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Garmpi A, Nonni A, Sakellariou S, Margonis GA, Spartalis E, Schizas D, Andreatos N, Magkouti E, Grivas A, Kontzoglou K, Weiss MJ, Antoniou EA. Angiomyolipoma of the Liver: A Rare Benign Tumor Treated with a Laparoscopic Approach for the First Time. In Vivo. 2017;31:1169-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Romano F, Franciosi C, Bovo G, Cesana GC, Isella G, Colombo G, Uggeri F. Case report of a hepatic angiomyolipoma. Tumori. 2004;90:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mao JX, Teng F, Liu C, Yuan H, Sun KY, Zou Y, Dong JY, Ji JS, Dong JF, Fu H, Ding GS, Guo WY. Two case reports and literature review for hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: Pitfall of misdiagnosis. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:972-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Leong WHJ, Tan XHA, Salazar E. More than Pus - Primary Hepatic Epithelioid Angiomyolipoma Masquerading as Liver Abscess. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2021;15:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kai K, Miyosh A, Aishima S, Wakiyama K, Nakashita S, Iwane S, Azama S, Irie H, Noshiro H. Granulomatous reaction in hepatic inflammatory angiomyolipoma after chemoembolization and spontaneous rupture. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9675-9682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tajima S, Suzuki A, Suzumura K. Ruptured hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7:369-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cai X, Sun S, Deng Y, Liu J, Pan S. Hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma is scattered and unsuitable for surgery: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2023;51:3000605231154657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, Schmithorst VJ, Laor T, Brody AS, Bean J, Salisbury S, Franz DN. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1041] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gennatas C, Michalaki V, Kairi PV, Kondi-Paphiti A, Voros D. Successful treatment with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in a patient with perivascular epithelioid cell tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bergamo F, Maruzzo M, Basso U, Montesco MC, Zagonel V, Gringeri E, Cillo U. Neoadjuvant sirolimus for a large hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/