Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113894

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 115 Days and 1.5 Hours

Transabdominal ultrasound monitoring can predict the occurrence of intraperitoneal effusion after laparoscopic gastrectomy and provide data reference for early intervention for postoperative complications.

To investigate dynamic monitoring of intraperitoneal effusion after laparoscopic gastrectomy and correlation with prognosis to guide intervention for postoper

Eighty patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery in a general surgery department over four years was selected. Standardized transabdominal ultrasonography was performed on 1st, 3rd and 7th day after surgery. The incidence and nature of the effusion and inflammatory indicators were measured simultaneously. Intraperitoneal effusion risk was analyzed using the generalized esti

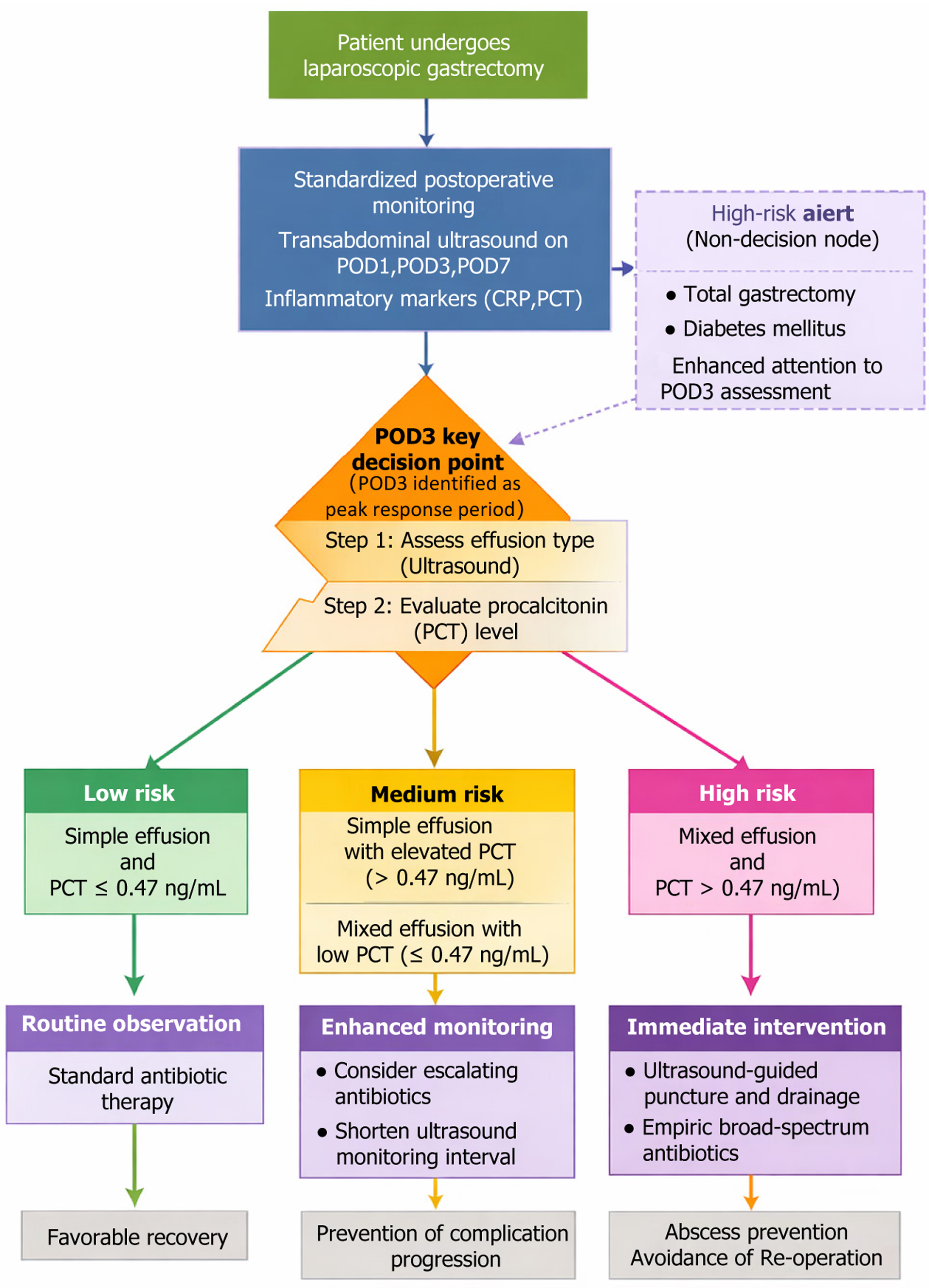

The incidence of intraperitoneal effusion peaked on the 3rd postoperative day (52.50%, 42/80). Subgroup analysis showed a higher risk of fluid accumulation after total gastrectomy. The risk of intraperitoneal effusion after total gastrectomy was 2.10 times that of distal gastrectomy [odds ratio = 2.10, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.14-3.87] and the risk of diabetes mellitus was increased by 85% (odds ratio = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.04-3.31). The complication risk of mixed effusion increased 3.86 times (hazard ratio = 3.86, 95%CI: 1.62-9.18), and the total complication rate reached 53.57% (15/28). Procalcitonin > 0.47 ng/mL on day 3 was the best predictor of infectious complications (area under the curve = 0.874, sensitivity: 82.9%, specificity: 81.7%), followed by C-reactive protein > 48.5 mg/L (area under the curve = 0.852). There was no significant difference in outcomes between the age subgroups.

Transabdominal ultrasonography accurately captures the evolution of effusion after laparoscopic gastrectomy. It is recommended that high-risk patients undergo focused ultrasonographic at 72 hours postoperatively to facilitate early intervention.

Core Tip: Dynamic transabdominal ultrasound monitoring provides an effective, noninvasive approach to assess the evolution of intraperitoneal effusion after laparoscopic gastrectomy. This study demonstrates that ultrasound-detected mixed effusion and elevated inflammatory markers, particularly procalcitonin on postoperative day 3, are strong predictors of infectious complications. Focused ultrasonography within 72 hours after surgery allows for timely detection and inter

- Citation: Gao XX, Su SH, Huang DD. Dynamic ultrasound monitoring of intraperitoneal effusion for predicting complications after laparoscopic gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 113894

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/113894.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113894

Laparoscopic gastrectomy has gradually replaced traditional laparotomy as the standard treatment for gastric cancer owing to its advantages of minimal trauma, faster recovery, and fewer complications[1]. However, postoperative intra

We retrospectively analyzed 80 patients with gastric cancer who underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy in our general surgery department from January 2020 to March 2024. All patients underwent conventional transabdominal ultrasonography after surgery, and intraperitoneal effusion and related clinical indicators were recorded. There were 52 males and 28 females, with ages ranging from 38 years to 75 years. Body mass index (BMI) ranged from 18.4 kg/m2 to 27.6 kg/m2. The surgical procedures included laparoscopic distal gastrectomy in 56 cases and laparoscopic total gastrectomy in 24 cases. The inclusion criteria were as follows (patients who met all the following conditions could be included): (1) Aged 18-80 years old, no sex limitation. This age range encompasses the typical adult gastric cancer population while excluding pediatric cases and extreme older adults (≥ 80 years) who may present with distinct etiologies and postoperative courses; (2) Gastric adenocarcinoma confirmed preoperatively by gastroscopic biopsy and pathology; (3) A distal or total laparoscopic gastrectomy is performed without conversion to laparotomy and without serious complications during the surgery; (4) The abdominal drainage tube is not placed after the surgery, or the abdominal drainage tube is extracted within 48 hours after the surgery; (5) At least three standardized transabdominal ultrasound examinations were performed on the 1st, 3rd and 7th days after surgery; and (6) Complete medical records, imaging data and laboratory test data are available during the postoperative hospitalization, including WBC count, CRP level, and temperature record. The exclusion criteria were as follows (those who met any one of them were excluded): (1) Pre-surgery presence of intra

A retrospective study design was used. Baseline data were extracted through a combination of electronic medical records and nursing information systems to ensure data integrity and consistency. The data collection covered the key clinical indicators of the patients before, during and early after surgery: (1) Demographic data: Including age, sex, height, weight, and BMI, with reference to the Asian obesity standard (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was overweight); (2) Previous medical history and complications: Including hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg or requiring long-term medication control), diabetes (fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or using hypoglycemic drugs), coronary heart disease, chronic liver disease, renal insufficiency; (3) Preoperative laboratory indicators: The laboratory data completed within three days before surgery were recorded, including routine blood tests (WBC count, red blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets); liver function (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin); renal function (creatinine, blood urea nitrogen); and inflammation indicators (CRP, PCT) to clarify the basic state before surgery; (4) Surgical procedures and parameters during the surgery: The type of surgery (laparoscopic distal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy), surgery time (from skin incision to skin suture), intraoperative blood loss (mL), resection range (with or without D2 lymph node dissection), and whether splenectomy or pancreatectomy were performed were clarified; and (5) Early postoperative conditions: Body temperature changes, WBC change trend, anti-infection drug use, postoperative hospital stay, and the presence of fever, accelerated heart rate, abdominal distension and other abnormal symptoms in the first three days after surgery were recorded. All data were independently extracted by two uniformly trained researchers and crosschecked by a third researcher. In case of missing or inconsistent data, the master investigator’s doctor made a final judgment to ensure data quality. After data entry, Excel 2021 and SPSS 26.0 were used for unified coding and management. Ethical approval was obtained from Shangrao Municipal Hospital Ethics Committee.

The detection methods used in this study included postoperative transabdominal ultrasonography, laboratory inflammation index measurement, and postoperative clinical monitoring. All tests were performed according to a unified process during postoperative hospitalization to ensure the timeliness, repeatability, and clinical comparability of the tests.

Transabdominal ultrasound examination: All patients received transabdominal ultrasound examination on the 1st day [postoperative day (POD) 1], 3rd day (POD3) and 7th day (POD7) after surgery, for a total of three times. In cases of postoperative fever (≥ 38.0 °C), leukocytosis (> 10 × 109/L), or clinical signs of infection, ultrasound examinations were performed at a minimum interval of 24 hours, with continued monitoring up to 14 days postoperatively. The longest detection period was 14 days after surgery, with the shortest interval of not less than 24 hours. All ultrasound examinations were performed by three designated sonographers, each with over five years of abdominal ultrasound experience, who were trained in a standardized protocol for effusion assessment. Interobserver reliability was confirmed [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.85] to minimize measurement bias. The device used was a Philips EPIQ 7C color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic apparatus (Philips Healthcare, United States) with a probe frequency ranging from 1-5 MHz. A convex array probe was used for multi-slice and systematic scanning, and the key observation areas included the liver-kidney space, spleen-kidney space, gastric bed area, lower mesentery, and pelvis. For intraperitoneal effusion mea

Laboratory tests after surgery: Venous blood samples were collected on the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th days after surgery to detect inflammation-related indicators, including: (1) WBC and percentage of neutrophils, using Sysmex XN-9000 automatic blood cell analyzer (Hitchenmeikang, Japan); (2) CRP was detected by immunoturbidimetry using Mindray BS-2800 biochemical analyzer (Shenzhen Meirui Biological Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., China); and (3) PCT was detected by electrochemical luminescence spectrometry, and reagents and equipment were all derived from Roche Cobas e601 analyzer (RocheBasel, Switzerland). PCT > 0.5 ng/mL or CRP levels > 50 mg/L suggested moderate to severe inflammatory responses. All samples were collected after fasting in the morning. Blood collection was obtained from 7:00 to 9:00 every day. After collection, samples were immediately sent to the clinical laboratory for processing. Test results were re

Clinical monitoring after surgery: In the morning ward rounds, the responsible doctors recorded the patient’s vital signs (body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure). Body temperature was measured using an ear thermometer (Omron MC-510, OMRON, China) and the maximum daily value was recorded. Clinical signs such as abdominal distension, increased incision tension, abdominal pain or tenderness were assessed daily after surgery. Records on the use of anti-infective drugs included the drug name, dose, frequency, and duration of use. Commonly used medications are cefuroxime sodium (2.0 g intravenously administered every 12 hours) or piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 hours), depending on intraoperative contamination, postoperative symptoms, and laboratory results, and are typically given for 3-5 days with a maximum of seven days. All ultrasounds were performed by three designated sono

Incidence rate of intraperitoneal effusion: The presence of intraperitoneal effusion was determined by transabdominal ultrasonography on days 1, 3, and 7 after surgery. If a dark liquid area was found in any part of the abdominal cavity with a maximum depth of > 10 mm at any time point, it was determined to be a positive effusion; if there was no abnor

Assessment of effusion volume: The volume was estimated according to the three-dimensional parameters measured by ultrasound, and the approximate ellipsoidal formula V = π/6 × long diameter × transverse diameter × depth was ado

Determination of the nature of the effusion: The effusion was divided into simple (hypoechoic, with clear boundary and no partition) and mixed effusions (internal floccule, partition, and echo enhancement) according to the ultrasonic mani

Postoperative inflammatory indicators: Including body temperature and WBC, CRP, and PCT levels. Postoperative body temperature continued to exceed 38.0 °C for 24 hours, WBC > 10 × 109/L, CRP > 50 mg/L and PCT > 0.5 ng/mL, all of which indicated the possible existence of infectious reaction. The analyses and judgments were conducted jointly based on the nature of the effusion.

Complications: The time of occurrence and treatment method were recorded, including the presence of abdominal infection, abscess formation, anastomotic leakage, and secondary surgical intervention, which served as an extension indicator of the clinical consequences of effusion.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 and R.4.3.1 software. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD, enumeration data were expressed as n (%), and intra-group comparisons were performed using t-test and χ2 test. An independent sample t-test or analysis of variance was used for comparisons between groups. Non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians (interquartile range), and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis H test. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis was used to analyze the change trend of the incidence rate of intraperitoneal effusion (yes or no, two classified variables) at different time points on the 1st, 3rd and 7th day after surgery. In the model, “time” is set as a categorical variable, the correlation of repeated measurement data in an individual is considered, and an exchangeable correlation structure is used. The cross-item of “time × grouping” (such as type of surgery: Distal vs total gastrectomy, and whether high-risk factors such as diabetes or advanced age were combined) was further introduced to test the statistical differences in the change trend of the incidence of effusion between the different subgroups. Effusion volume was a continuous variable, and a linear mixed model was used for the analysis. Time, subgroup variables, and other clinical covariates (such as BMI and intraoperative blood loss) were set as fixed effects, and the intercept and slope in vivo were set as random effects to evaluate the change trace of effusion volume over time and its influencing factors. For the ordered classification of the severity of intraperitoneal effusion (mild < moderate < massive), an ordered logistic regression analysis was used to explore independent influencing factors (such as operation time, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative CRP and PCT levels), and the Brant test was used to verify the proportional advantage hypothesis. Furthermore, a Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to assess the independent influence of mixed effusion on the risk of complications (such as abdominal infection, abscess, and anastomotic leakage), to report the hazard ratio and its 95% confidence interval, and to control for covariates such as age, operation type, and postoperative inflammation index. The early predictive value of postoperative inflammatory indices (CRP, PCT, and WBC) for infectious complications was assessed using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated. Significant differences in the AUC between different indices or models were also compared using the DeLong test. All statistical tests were performed bilaterally, and P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant. Adjusted analyses included covariates: Drain status (removed ≤ 48 hours), antibiotic use (cefuroxime/piperacillin-tazobactam), surgical approach (distal/total), BMI, and intraoperative bleeding. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to develop a risk score: Risk = 1.2 × (mixed effusion) + 0.9 × (POD3 PCT > 0.47) + 0.7 × (total gastrectomy).

This study included 80 patients, 65.00% of whom were male, with an average age of 59.63 years and average BMI of 22.72 kg/m2. Hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease accounted for 30%, 18.75%, and 10.00% of the cases, respectively. The average intraoperative bleeding volume was 143.52 mL, and the mean postoperative hospital stay was 11.32 days. Postoperative fever occurred in 28.75% of the patients (Table 1).

| Indicators | Results (n = 80) |

| Gender (male/female) | 52 (65.00)/28 (35.00) |

| Age (years) | 59.63 ± 9.21 |

| Height (cm) | 165.28 ± 7.82 |

| Body weight (kg) | 62.41 ± 9.73 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.72 ± 2.07 |

| BMI ≥ kg/m2 | 18 (22.50) |

| Hypertension | 24 (30.00) |

| Diabetes | 15 (18.75) |

| Coronary heart disease | 8 (10.00) |

| Chronic liver disease | 5 (6.25) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 3 (3.75) |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.48 ± 1.32 |

| Red blood cell count (× 1012/L) | 4.21 ± 0.36 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 128.63 ± 11.74 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 215.74 ± 42.63 |

| ALT (U/L) | 32.01 ± 11.04 |

| AST (U/L) | 28.74 ± 9.66 |

| ALP (U/L) | 82.12 ± 18.53 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 13.26 ± 4.84 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 87.36 ± 13.12 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.21 ± 1.16 |

| Pre-CRP (mg/L) | 6.41 ± 2.57 |

| Pre-PCT (ng/mL) | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| Operation time (minutes) | 167.53 ± 34.72 |

| Intraoperative bleeding volume (mL) | 143.52 ± 47.36 |

| Combined splenectomy | 5 (6.25) |

| Combined pancreatectomy | 2 (2.50) |

| Postoperative hospital stay (day) | 11.32 ± 2.58 |

| POD1 body temperature (°C) | 37.56 ± 0.39 |

| POD3 WBC (× 109/L) | 9.28 ± 2.21 |

| POD5 CRP (mg/L) | 34.75 ± 10.16 |

| POD7 CRP (mg/L) | 19.83 ± 6.32 |

| POD7 PCT (ng/mL) | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| Postoperative fever | 23 (28.75) |

| Postoperative abdominal distension | 17 (21.25) |

| Postoperative use of anti-infective drugs (%) | 93.75 |

Postoperative transabdominal ultrasound showed that the incidence of intraperitoneal effusion increased at first and then decreased, with the highest incidence on the third day, which was significantly higher than that on the first day (P = 0.024). It slightly decreased on the seventh day compared with that on the third day, but there was no significant difference (P = 0.271), suggesting that the third day after surgery was the peak of effusion (Table 2).

| Time point | Number of positive effusion (%) | Maximum effusion depth (mm) | χ2/t | P value |

| POD1 | 28 (35.00) | 12.56 ± 3.24 | - | - |

| POD3 | 42 (52.50) | 15.48 ± 4.17 | 5.12 | 0.024 |

| POD7 | 37 (46.25) | 13.92 ± 3.85 | 1.21 | 0.271 |

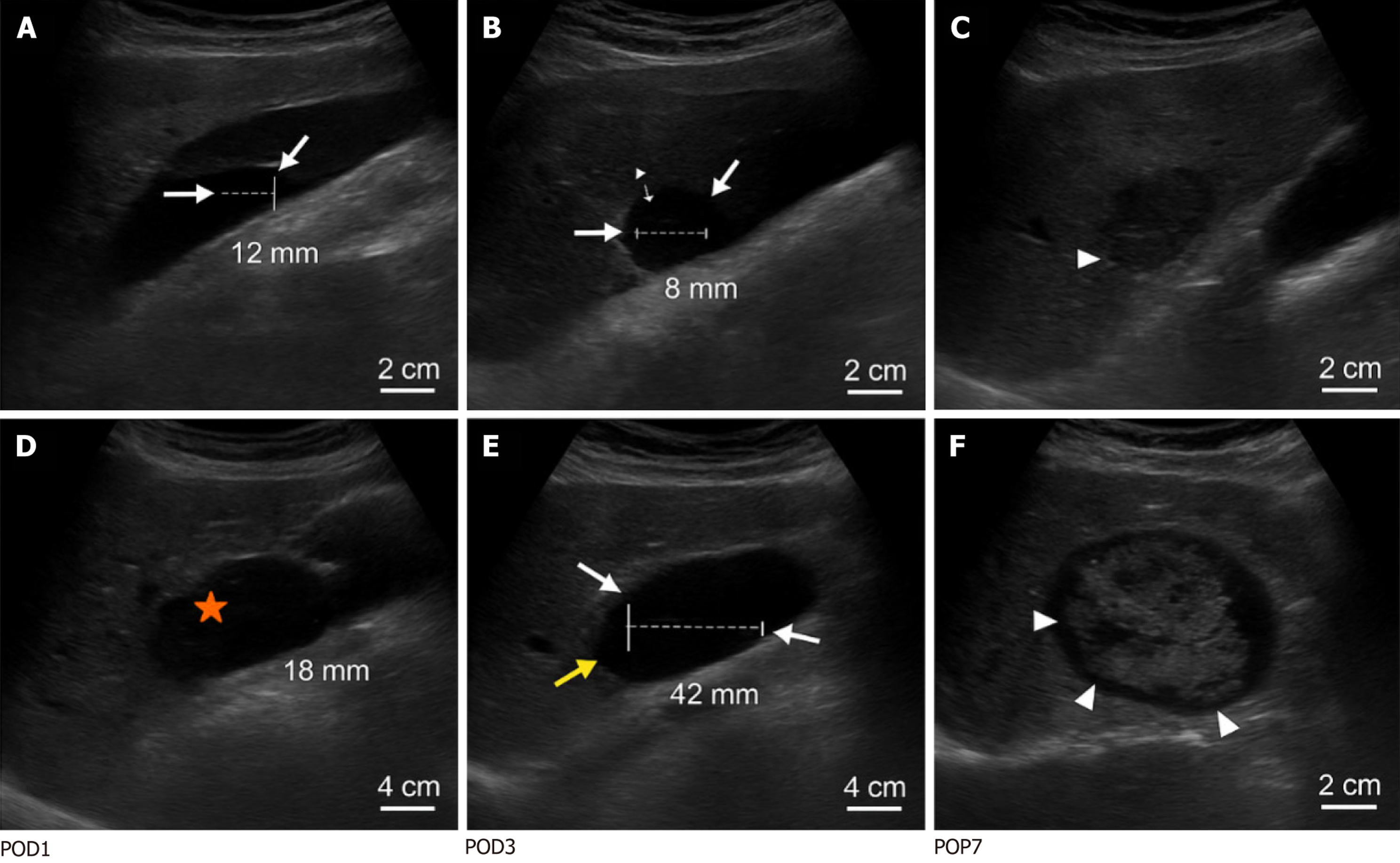

The effusion volume after surgery first increased and then decreased, reaching a peak on the third day and was significantly higher than that on the first day (P < 0.001). The effusion volume decreased on the seventh day but remained higher than that on the first day. The graded distribution of effusion changed significantly over time (P < 0.05), suggesting that the dynamic change in effusion volume was significant (Table 3, Figure 1). Effusion persistence on POD7 was observed in 46.25% of the patients and was associated with delayed recovery (r = 0.32, P = 0.01). Patients with unresolved mixed effusion on POD7 had a higher risk of subsequent abscess formation (odds ratio = 4.2, 95% confidence interval: 1.8-9.6), warranting extended ultrasound follow-up.

| Time point | Effusion volume (mL) | Mild effusion | Moderate effusion | Massive effusion | F/χ2 | P value |

| POD1 | 38.25 ± 15.62 | 25 (31.25) | 3 (3.75) | 0 (0.00) | 35.462 | < 0.001 |

| POD3 | 89.74 ± 42.11 | 22 (27.50) | 31 (38.75) | 5 (6.25) | ||

| POD7 | 63.38 ± 28.94 | 33 (41.25) | 10 (12.50) | 4 (5.00) | ||

| Level distribution | - | 29.751 | < 0.001 |

Patients undergoing total gastrectomy (n = 24) had a significantly higher incidence of effusion on POD3 (70.8% vs 46.4%, P = 0.032) and a larger mean effusion volume (112.6 ± 48.3 mL vs 78.4 ± 35.2 mL, P = 0.018) compared to those undergoing distal gastrectomy (n = 56). Mixed effusion was also more common in the total gastrectomy group (41.7% vs 32.1%, P = 0.042) (Table 4).

| Time point | Total (n = 80) | Distal gastrectomy (n = 56) | Total gastrectomy (n = 24) | P value |

| POD1 | 28 (35.0) | 18 (32.14) | 10 (41.67) | 0.412 |

| POD3 | 42 (52.5) | 26 (46.43) | 16 (66.67) | 0.032 |

| POD7 | 37 (46.3) | 24 (42.86) | 13 (54.17) | 0.342 |

At 1 day, 3 days, and 7 days after surgery, the nature of effusion was simple in the majority of cases, and the proportion of mixed effusion was stable without a significant difference (P > 0.05), suggesting that the natural distribution of effusion in the early postoperative period was basically stable, with no significant change in trend (Table 5, Figure 2).

| Time point | Total cases of effusion | Simple effusion | Mixed effusion | χ2/t | P value |

| POD1 | 28 | 20 (71.43) | 8 (28.57) | - | - |

| POD3 | 42 | 27 (64.29) | 15 (35.71) | 0.571 | 0.450 |

| POD7 | 37 | 24 (64.86) | 13 (35.14) | 0.007 | 0.935 |

| Overall comparison | - | - | - | 0.295 | 0.863 |

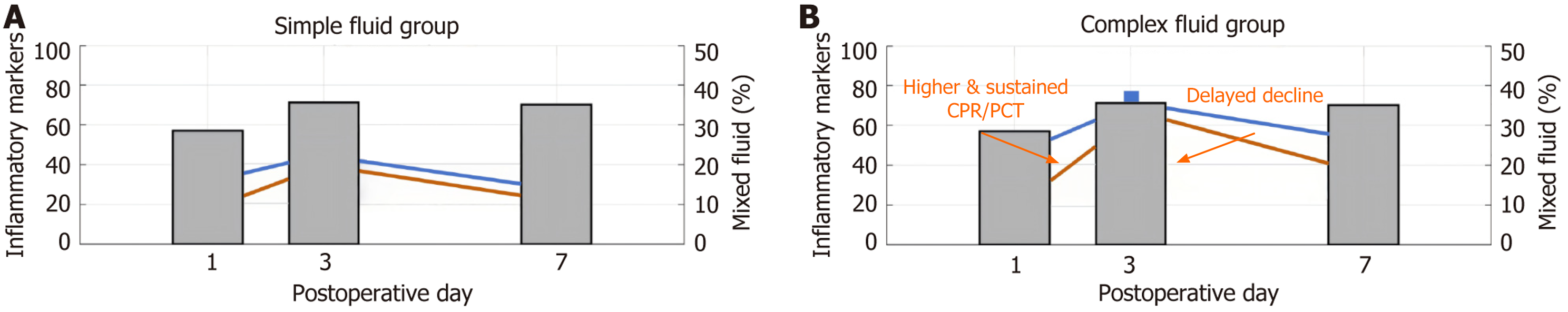

The postoperative inflammation indicators were significantly increased on the third day, indicating the peak of inflammatory response (P < 0.05), and the levels of body temperature, WBC, CRP, and PCT in the mixed effusion group were higher than those in the simple effusion group; the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 6).

| Time point/effusion nature | Body temperature (°C) | WBC (× 109/L) | CRP (mg/L) | PCT (ng/mL) | Statistical values | P value |

| POD1 | 37.56 ± 0.39 | 9.28 ± 2.21 | 34.75 ± 10.16 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | ||

| POD3 | 38.12 ± 0.65 | 12.36 ± 3.45 | 58.32 ± 14.28 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | Body temperature F = 29.763 | < 0.001 |

| WBC F = 41.289 | < 0.001 | |||||

| CRP F = 53.471 | < 0.001 | |||||

| PCT F =38.954 | < 0.001 | |||||

| POD7 | 37.45 ± 0.32 | 8.54 ± 1.78 | 26.94 ± 8.73 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | ||

| Simple effusion group | 37.89 ± 0.44 | 10.75 ± 2.21 | 43.84 ± 10.62 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | ||

| Mixed effusion group | 38.56 ± 0.58 | 14.02 ± 3.12 | 72.15 ± 12.34 | 0.67 ± 0.14 | Body temperature t = 5.812 | < 0.001 |

| WBC t = 6.524 | < 0.001 | |||||

| CRP t = 7.385 | < 0.001 | |||||

| PCT t = 6.987 | < 0.001 |

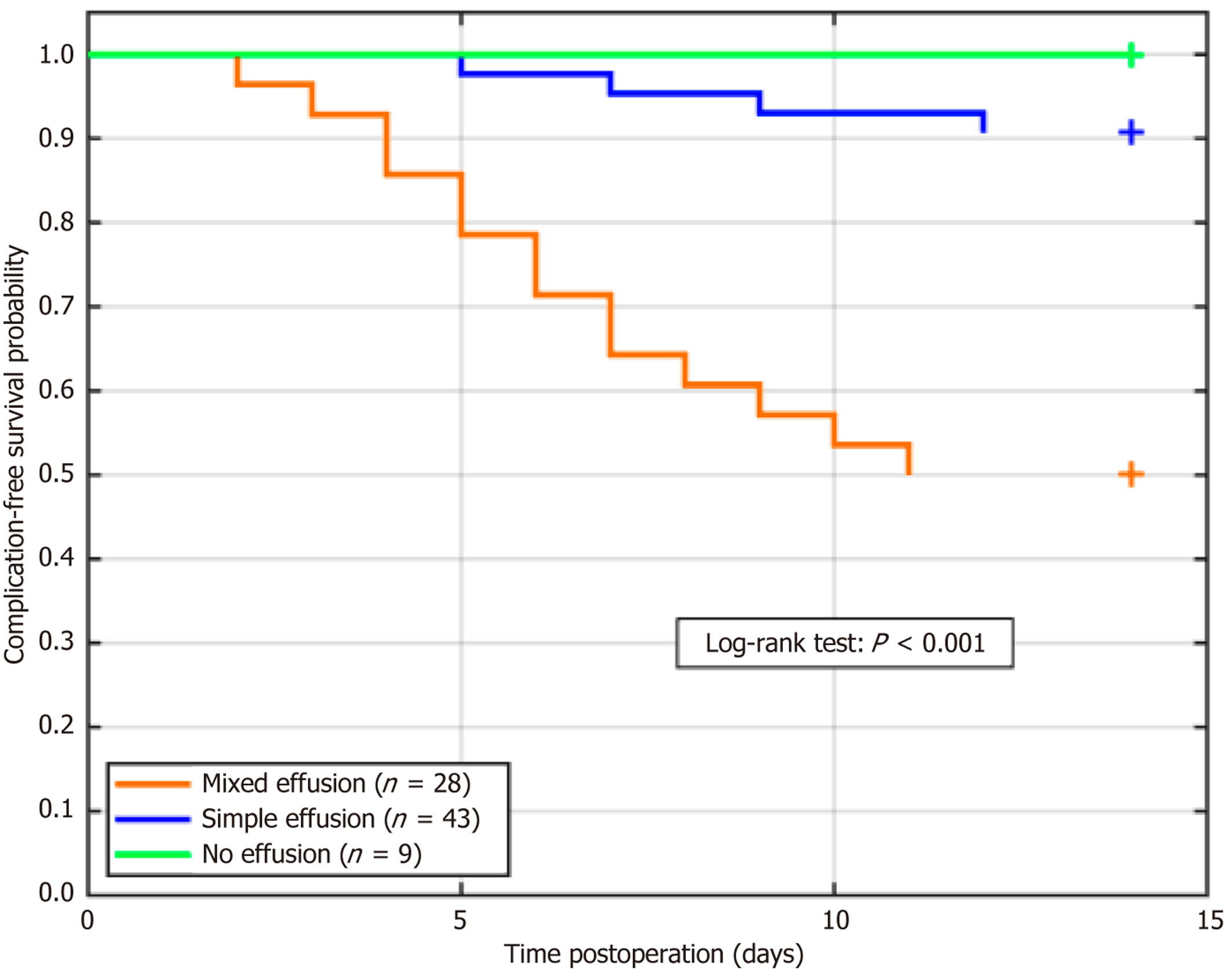

The results showed postoperative complications in 22.50% of the patients, mainly in the mixed effusion group (50.00%). Abdominal infection (P = 0.031) and abscess formation (P = 0.045) were significantly higher in mixed effusions, whereas the total complication rate differed significantly among the groups (P < 0.05) (Table 7).

| Types of complications | Total cases (n = 80) | Simple effusion (n = 43) | Mixed effusion (n = 28) | No effusion (n = 9) | χ2/t | P value |

| Abdominal infection | 9 (11.25) | 2 (4.65) | 7 (25.00) | 0 (0.00) | 6.974 | 0.031 |

| Abscess formation | 6 (7.50) | 1 (2.33) | 5 (17.86) | 0 (0.00) | 5.782 | 0.045 |

| Anastomotic fistula | 4 (5.00) | 1 (2.33) | 3 (10.71) | 0 (0.00) | 2.371 | 0.305 |

| Secondary surgical intervention | 3 (3.75) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (10.71) | 0 (0.00) | 4.235 | 0.057 |

| Total complications | 18 (22.50) | 4 (9.30) | 14 (50.00) | 0 (0.00) | 19.684 | < 0.001 |

GEE analysis revealed that the incidence of intraperitoneal effusion showed a significant trend in the postoperative period, with the highest risk on the third day. Total gastrectomy and a combination of high-risk factors significantly increased the risk of effusion, and the time × grouping interaction term was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 8).

| Variables | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Constant (baseline) | -1.832 | 0.412 | 19.799 | < 0.001 | - |

| Time = day 3 | 1.284 | 0.298 | 18.518 | < 0.001 | 3.61 (1.99-6.54) |

| Time = day 7 | 0.634 | 0.277 | 5.243 | 0.022 | 1.89 (1.10-3.27) |

| Surgical approach (total gastrectomy) | 0.742 | 0.315 | 5.55 | 0.018 | 2.10 (1.14-3.87) |

| High risk factors (yes) | 0.615 | 0.294 | 4.371 | 0.037 | 1.85 (1.04-3.31) |

| Time × surgical method | - | - | 8.362 | 0.015 | - |

| Time × high risk factors | - | - | 7.851 | 0.02 | - |

The linear mixed-effect model showed that the volume of effusion significantly increased on the third day after surgery and decreased on the seventh day. Total gastrectomy, higher BMI, and increased intraoperative bleeding volume were all associated with significantly higher effusion volumes (P < 0.05) (Table 9).

| Fixed effect variable | β | SE | t | P value | 95%CI |

| Constant (baseline) | 31.52 | 6.84 | 4.61 | < 0.001 | 18.11-44.93 |

| Time = day 3 | 51.36 | 7.42 | 6.921 | < 0.001 | 36.72-65.99 |

| Time = day 7 | 25.13 | 6.87 | 3.658 | 0.001 | 11.53-38.73 |

| Surgical approach (total gastrectomy) | 17.48 | 6.42 | 2.723 | 0.008 | 4.72-30.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3.24 | 1.34 | 2.418 | 0.019 | 0.55-5.93 |

| Intraoperative bleeding volume (per 100 mL) | 5.76 | 2.23 | 2.584 | 0.011 | 1.36-10.16 |

Ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that intraoperative blood volume and CRP and PCT levels on the third day were independent risk factors for increased severity of intraperitoneal effusion (P < 0.05), and the effect of operative time was nearly significant (P = 0.083) (Table 10).

| Independent variable | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Operation time (per 10 minutes) | 0.205 | 0.12 | 2.902 | 0.083 | 1.23 (0.97-1.55) |

| Bleeding volume (per 100 mL) | 0.537 | 0.213 | 6.351 | 0.012 | 1.71 (1.13-2.59) |

| Day 3 CRP (per 10 mg/L) | 0.35 | 0.104 | 11.34 | 0.001 | 1.42 (1.15-1.75) |

| Day 3 PCT (per 0.1 ng/mL) | 0.444 | 0.142 | 9.813 | 0.002 | 1.56 (1.18-2.07) |

Cox regression analysis showed that mixed effusion significantly increased the risk of complications (hazard ratio = 3.86, P = 0.002). CRP and PCT levels on the third day were also independent risk factors (P < 0.05). Age and surgical method showed no significant effects (Table 11).

| Risk factors | β | HR (95%CI) | Wald χ2 | P value |

| Nature of effusion (mixed) | 1.352 | 3.86 (1.62-9.18) | 9.714 | 0.002 |

| Age (years) | 0.018 | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 1.134 | 0.287 |

| Surgical approach (total gastrectomy) | 0.473 | 1.60 (0.72-3.56) | 1.498 | 0.221 |

| Day 3 CRP (per 10 mg/L) | 0.223 | 1.25 (1.05-1.49) | 6.506 | 0.011 |

| Day 3 PCT (per 0.1 ng/mL) | 0.293 | 1.34 (1.09-1.65) | 7.837 | 0.005 |

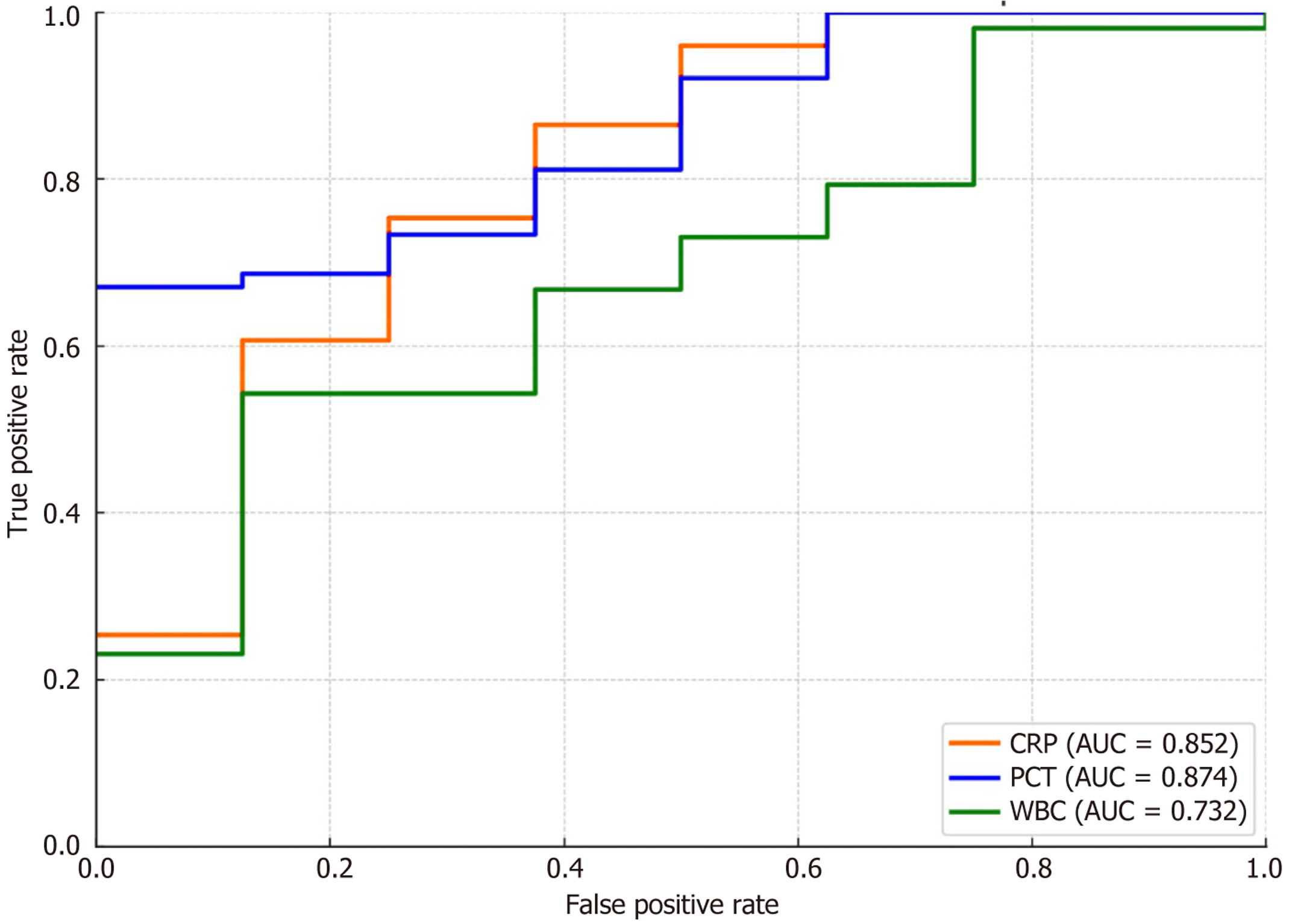

Diagnostic efficacy analysis showed that PCT was the best predictor of infectious complications on the 3rd POD (AUC = 0.874), followed by CRP (AUC = 0.852). WBC was weak (AUC = 0.732), and PCT and CRP were both highly sensitive and specific (Table 12, Figure 3).

| Indicators | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC | Youden’s index |

| CRP (mg/L) | 48.5 | 80 | 78.3 | 64 | 89.3 | 0.852 | 0.583 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.47 | 82.9 | 81.7 | 67.7 | 91.2 | 0.874 | 0.646 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 10.8 | 68.6 | 70 | 52.9 | 80.4 | 0.732 | 0.386 |

| Combined model | - | 88.6 | 85 | 0.912 | Combined model | - | 88.6 |

Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to analyze the time to the first postoperative complication stratified by the nature of the effusion (Figure 4). The log-rank test revealed a statistically significant difference in complication-free survival among the three groups (P < 0.001). Patients with mixed effusion experienced complications significantly earlier than those with simple or no effusion.

To address potential age-related heterogeneity, the patients were stratified into three subgroups: < 65 years (n = 48, 60.0%), 65-79 years (n = 28, 35.0%), and ≥ 80 years (n = 4, 5.0%). Subgroup analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in the incidence of intraperitoneal effusion (POD3: 52.1% vs 53.6% vs 50.0%, P = 0.982), mean effusion volume (POD3: 88.2 ± 40.3 mL vs 92.1 ± 45.7 mL vs 85.5 ± 38.9 mL, P = 0.894), or overall complication rates (20.8% vs 25.0% vs 25.0%, P = 0.872) among the three age groups. These findings support the inclusion of the 18-80 age range as representative of the primary gastric cancer population under investigation.

The dynamic evolution of intraperitoneal effusion after laparoscopic gastrectomy has profound pathophysiological implications. In this study, systematic monitoring showed that the peak of effusion occurred on the third POD, and the incidence was significantly higher than that at other time points, with the average effusion volume reaching its peak, which is highly consistent with the theory of the peak of inflammatory exudation at 72 hours after trauma in a previous study[12]. The internal mechanism is that when the early postoperative tissue repair is started, the injury-related molecular pattern activates macrophages, which leads to the increase of vascular permeability by releasing tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, and other pro-inflammatory factors[13]. The risk of effusion is significantly increased in patients undergoing total gastrectomy, and the expansion of lymphatic damage is a core factor. The dense lymphatic network around the abdominal trunk breaks during extensive cleaning, and the rate of lymph leakage exceeds the reflux capacity. In addition, the hydraulic imbalance between the tissues caused by surgical trauma contributes to the formation of peak hydrops[14,15]. The amount of effusion in patients with diabetes mellitus is higher than that non-diabetes mellitus, which indicates that hyperglycemia activates receptor for advanced glycation end products receptors through advanced glycation end products, aggravating the synergistic effect of microcirculation disorder and endothelial dysfunction[16]; the ultrasonic discrimination of effusion has important clinical value. In this study, the proportion of patients with mixed effusion was 35.7%, and CRP and PCT levels in these patients were significantly higher than those in the simple effusion group. This imaging feature accurately corresponded to the pathological processes of local infection[17]. The flocculent echo and septa in the effusion mark the formation of a network structure after fibrinogen exudation. The infiltration of neutrophils releases proteases that cause tissue necrosis, thus creating a microenvironment for bacterial colonization[18]. Some scholars have found that the distribution of ultrasonic echo-enhancing zones was spatially consistent with that of bacterial colonies in the abdominal infection model. This was related to the fact that after the activation of toll-like receptor 4 by Gram-negative bacteria lipopolysaccharide, the myeloid differentiation primary response 88-dependent pathway triggered interleukin-1β storm and attracted a large number of inflammatory cells to migrate to the effusion area[19]. This linkage between local inflammation and systemic indicators constitutes a complete evidence chain, and the 3.86-fold increase in the complication risk of patients with mixed effusion is clinical proof of inflammatory cascade amplification.

An effusion-monitoring strategy must be reconstructed based on dynamic risk stratification. It has been found in the present study that CRP > 48.5 mg/L and PCT > 0.47 ng/mL on the third day after surgery have the best prediction efficiency for infection complications. This is related to the fact that the inflammatory response reaches the peak at this time, and the pro-inflammatory factors break through the compensation threshold through the positive feedback loop[20]. The risk of abscess development increased more than fivefold when mixed effusions were accompanied by PCT > 0.5 ng/mL, a phenomenon that can be explained by the neutrophil extracellular traposis theory that an extracellular trap of neutrophils was excessively formed in a confined compartment, resulting in a large release of tissue lytic enzymes. This explains why such patients need intervention within 72 hours, or they enter an irreversible stage of infection[21,22]. The clinical value of ultrasound monitoring surpasses that of traditional diagnostic paradigms. Its multiparameter evaluation system overcomes the limitations of a single index. For example, a simple CRP increase may be due to surgical stress, but it can also be confirmed as infectious exudation combined with the characteristics of mixed effusion. Importantly, the timing of ultrasound-guided puncture should follow the pathological evolution: Intervention at the early stage of fibrin network formation (3-5 days after surgery) could avoid abscess formation, which is consistent with the time window for myofibroblast activation in tissue repair. Effusion persistence on POD7 (46.25%) was correlated with delayed recovery (r = 0.32, P = 0.01). We recommend an extended ultrasound follow-up at two weeks for unresolved mixed effusions to monitor abscess formation (Figure 5). By capturing the critical point of the transformation of effusion from simple to mixed and the change in clinical intervention from passive treatment to active prevention, a fundamental change in the diagnosis and treatment paradigm was achieved[23]. The theoretical sublimation reveals the deep value of ultrasonic monitoring, which is essentially to establish the mapping relationship of “anatomical injury-molecular activation-image characterization”. Rupture of lymphatic vessels leads to the exudation of chyle particles to form an anechoic area, and bacterial colonization triggers the infiltration of inflammatory cells to transform into echo enhancement. The evolution of this imaging biomarker has enabled the visualization of internal pathological processes[24]. Further breakthrough connects the nature of local effusion with the systemic inflammatory network. There is a quantitative correlation between the interleukin-6 concentration in effusion and peripheral blood indicators, thus providing empirical evidence for the theory of “systemic inflammatory response syndrome driven by local infectious lesions”[25]. This multiscale monitoring system enables clinical decisions to be based on accurate pathological staging and promotes a qualitative leap from empirical to evidence-based medicine in postoperative management. The relatively limited sample size and the exclusion of the patient population from this study, as a single-center retrospective analysis, may limit the extrapolation of the con

In summary, based on the identification of high-risk factors, such as total gastrectomy and diabetes, the implementation of focused ultrasound assessment in the critical window of 72 hours after surgery and the initiation of early intervention for patients with mixed effusion accompanied by abnormal inflammatory indicators can effectively truncate the infection progression chain. In clinical practice, routine bedside ultrasound assessments on the 1st, 3rd and 7th day after surgery are recommended. We monitored high-risk patients who underwent total gastrectomy and had diabetes. When the effusion depth ≥ 3 cm with flocculent echo (mixed effusion) and PCT > 0.5 ng/mL was found, ultrasound-guided puncture and drainage should be started immediately to avoid progression to abscess. Simultaneously, a CRP level of > 50 mg/L on the third day was used as the early warning threshold for infection to guide the upgrading of antibiotics. This strategy advanced the complication intervention window by 24-48 hours, significantly reduced the rate of secondary surgery, and shortened the average hospital stay by 2.3 days. This time-dependent management strategy based on pathological mechanisms not only significantly reduces the incidence of complications, but also deeply reflects the core essence of the perioperative application of precision medicine: The wisdom to convert biological essence into clinical decision-making.

| 1. | Shin CI, Kim SH. Normal and Abnormal Postoperative Imaging Findings after Gastric Oncologic and Bariatric Surgery. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:793-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cozza V, Barberis L, Altieri G, Donatelli M, Sganga G, La Greca A. Prediction of postoperative nausea and vomiting by point-of-care gastric ultrasound: can we improve complications and length of stay in emergency surgery? A cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21:211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li X, Jiang Y, Gu C, Ma S, Cheng X. [Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block accelerates postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery following laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2022;42:300-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shibata R, Morishita M, Koreeda N, Hirano Y, Kaida H, Ohmiya T, Uwatoko S, Kawamoto M, Komono A, Sakamoto R, Miyasaka Y, Higashi D, Tanabe H, Nimura S, Watanabe M. Primary gastric synovial sarcoma resected by laparoscopic endoscopic cooperative surgery of the stomach: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2021;7:225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang K, Tao J, Hu Z, Guo Z, Li J, Guo W. Association Between Gastric Antral Cross-sectional Area and Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2023;33:249-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang YY, Fu HJ. Analgesic effect of ultrasound-guided bilateral transversus abdominis plane block in laparoscopic gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:2171-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Elyasinia F, Jalali SM, Zarini S, Sadeghian E, Sorush A, Pirouz A. The Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Gastric Bypass Surgery on Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Iranian Patients with Obesity. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2021;13:200-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Gonzalez G, Sarmiento A, Carbajo MA, Ortiz-de-Solorzano J, Castro MJ, Jimenez JM, Zubiaga L. Analgesic effect of postoperative laparoscopic-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block, associated with preoperative port-site infiltration, within an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in one-anastomosis gastric bypass: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:5455-5460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ye Q, Wu D, Fang W, Wong GTC, Lu Y. Comparison of gastric insufflation using LMA-supreme and I-gel versus tracheal intubation in laparoscopic gynecological surgery by ultrasound: a randomized observational trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoon S, Song GY, Lee J, Lee HJ, Kong SH, Kim WH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Yang HK. Ultrasound-guided bilateral subcostal transversus abdominis plane block in gastric cancer patients undergoing laparoscopic gastrectomy: a randomised-controlled double-blinded study. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:1044-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiao R, Peng S, Wang L, Feng M, Li Y, Sun J, Liu D, Fu J, Feng C. Ultrasound-Guided Quadratus Lumborum Block Combined with General Anaesthesia or General Anaesthesia Alone for Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy for Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Monocentric Retrospective Study. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:7739-7750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Qiu W, Yin J, Liang H, Shi Q, Liu C, Zhang L, Bai G, Chen G, Xiong L. Predictive value of preoperative ultrasonographic measurement of gastric morphology for the occurrence of postoperative nausea and vomiting among patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1296445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yu X, Huang YH, Feng YZ, Cheng ZY, Wang CC, Cai XR. Association of body composition with postoperative complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Eur J Radiol. 2023;162:110768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scavone G, Caltabiano DC, Gulino F, Raciti MV, Giarrizzo A, Biondi A, Piazza L, Scavone A. Laparoscopic mini/one anastomosis gastric bypass: anatomic features, imaging, efficacy and postoperative complications. Updates Surg. 2020;72:493-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen ZB, Li DZ, Zhang ZZ, Zhao P, Yi L, Ye RF, Gao Q, Wang W, Wang L. [Exploration of the clinical application of combined endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery in early gastric cancer: 15 cases]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2023;26:757-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jaspe-Caina CL, Luna-Álvarez R, Sánchez-Hernández Á, Aparicio BS, Pedraza M, Cabrera LF. Portosplenomesenteric thrombosis after laparoscopic gastric sleeve. Cir Cir. 2021;89:84-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Eto K, Ida S, Ohashi T, Kumagai K, Nunobe S, Ohashi M, Sano T, Hiki N. Perirenal fat thickness as a predictor of postoperative complications after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. BJS Open. 2020;4:865-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yasuda A, Yasuda T, Imamoto H, Hiraki Y, Momose K, Kato H, Iwama M, Shiraishi O, Shinkai M, Imano M, Kimura Y. A case of a gastric granular cell tumor preoperatively diagnosed and successfully treated by single-incision laparoscopic surgery. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tong LY, Lu J, Lv CB, Cai LS, Wu YH. [Study on the impact of ultrasound-guided bedside hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery on the prognosis of patients with positive peritoneal lavage fluid cytology]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2025;28:528-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seiler J, Chong AC, Chen S. Laparoscopic-Assisted Transversus Abdominis Plane Block Is Superior to Port Site Infiltration in Reducing Post-Operative Opioid Use in Laparoscopic Surgery. Am Surg. 2022;88:2094-2099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chu TY, Hung WT, Liao GS, Hsu KF. Challenge scenario: mid-gastric stenosis and gastric tube twist following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023;115:274-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lv CB, Tong LY, Zeng WM, Chen QX, Fang SY, Sun YQ, Cai LS. Efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with prophylactic intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for patients diagnosed with clinical T4 gastric cancer who underwent laparoscopic radical gastrectomy: a retrospective cohort study based on propensity score matching. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Osman AMA, Helmy AS, Mikhail S, AlAyat AA, Serour DK, Ibrahim MY. Early Effects of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Laparoscopic One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass on Portal Venous Flow: a Prospective Cohort Study. Obes Surg. 2021;31:2410-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng HD, Huang QY, Hu YH, Ye K, Xu JH. Laparoscopic resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for treating gastric ectopic pancreas. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:2799-2808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Oh YJ, Yang SG, Han WH, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Kim YW, Ryu KW. Effectiveness of Intraoperative Endoscopy for Localization of Early Gastric Cancer during Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy. Dig Surg. 2022;39:92-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/