Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112416

Revised: August 26, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 179 Days and 4.4 Hours

Bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer is a very rare secondary cancer, which can cause biliary obstruction.

A 42-year-old male presented with right upper abdominal discomfort and jaun

This case indicates the possibility of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer and highlights the necessity of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with choledochoscopy in patients with suspicious malignant biliary obstruction.

Core Tip: Bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer is a very rare form of secondary malignancy that can lead to biliary obstruction. We herein report a case who developed right upper abdominal discomfort and jaundice following total gastrectomy for poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma. Subsequently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with choledochoscopy identified poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in the common bile duct. This case indicates the possibility of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer and highlights the necessity of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with choledochoscopy in patients with suspected malignant biliary obstruction.

- Citation: Li CK, Cao RR, Su DS, Ming J, Li YC, Shao XD, Qi XS. Diagnosis of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography combined with choledochoscopy: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112416

The incidence of malignant biliary obstruction is high in Asia and has been increasing globally, making it a serious threat to patients’ lives[1]. About 20% of patients with malignant biliary obstruction result from secondary cancer, including obstruction of intrahepatic bile duct due to parenchymal metastases, compression by enlarged lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament, local recurrence, or, rarely, intraluminal invasion of the bile duct. The most frequent primary cancers include gastric, colon, breast, kidney, and lung cancers[2]. It has been reported that 1.4%-2.3% of patients with gastric cancer developed biliary obstruction after curative resection, which was primarily associated with cancer metastasis[3]. In the absence of surgical gross specimens and autopsy, the diagnosis of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer is often difficult. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively review the findings of histology, immunohistochemical staining, magnetic resonance imaging, and especially endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) combined with choledochoscopy. Herein, we report a case of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer, where bile duct tissue was obtained using ERCP with choledochoscopy to achieve a positive pathological diagnosis, and a plastic stent was subsequently placed across the stenosis to relieve the obstruction.

A 42-year-old male patient presented with right upper abdominal discomfort for a duration of two weeks.

Two weeks before our admission, he experienced right upper abdominal discomfort, and his liver function tests were mildly elevated. Despite taking oral hepatoprotective medication, jaundice and biochemical markers progressively worsened.

The patient underwent total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis in April 2023. At that time, pathological examination revealed poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma with a signet ring cell component. Immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: Ki-67 (75%+), MutS protein homolog 6 (+), MutS protein homolog 2 (+), PMS1 protein homolog 2 (+), MutL protein homolog 1 (+), and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-2 (2+). Fluorescence in situ hybridization showed no HER-2 gene amplification. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with sindilizumab combined with capecitabine. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans showed no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis.

The patient reported no family history of malignant tumors.

His vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.5 °C; blood pressure, 122/80 mmHg; heart rate, 82 beats per minute; and respiratory rate, 16 breaths per minute. His abdominal signs were unremarkable.

Upon admission, laboratory investigations revealed the following: Aspartate aminotransferase 19.96 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 26.93 U/L, total bilirubin 198.9 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 133.9 μmol/L, and alkaline phosphatase 287.00 U/L. Viral hepatitis markers and autoimmune hepatitis antibodies were negative. Tuberculosis-related tests and tumor markers were unremarkable. Following hepatoprotective therapy in combination with percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage, repeat laboratory tests showed an increased total bilirubin level of 473.6 μmol/L with a direct bilirubin level of 383.8 μmol/L.

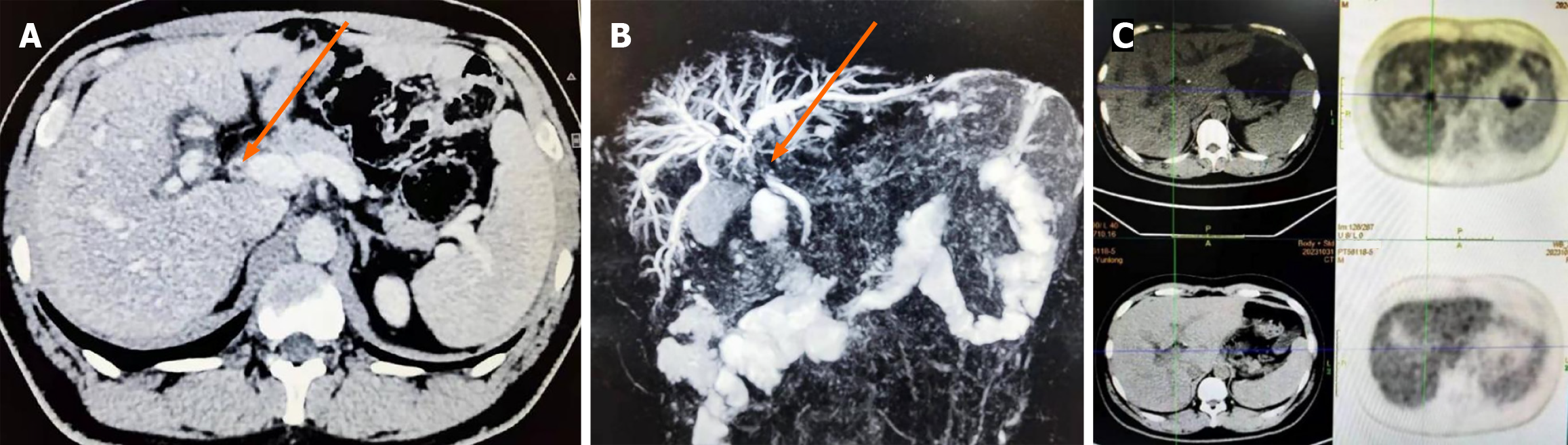

Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (Figure 1A), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Figure 1B), and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (Figure 1C) scans were performed. All imaging examinations demonstrated dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts near the hilum, along with stenoses in the common hepatic duct and common bile duct.

The patient was diagnosed with bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer by combined ERCP and choledochoscopy.

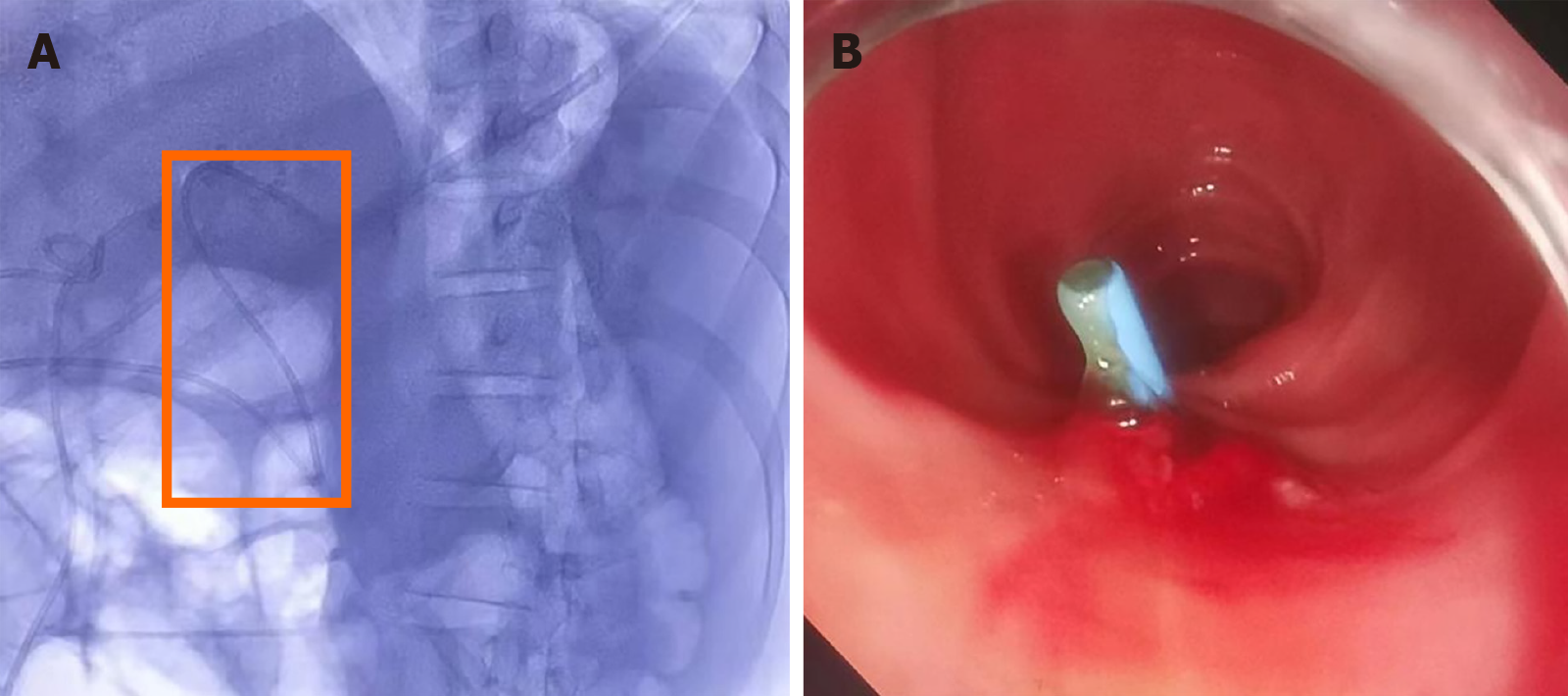

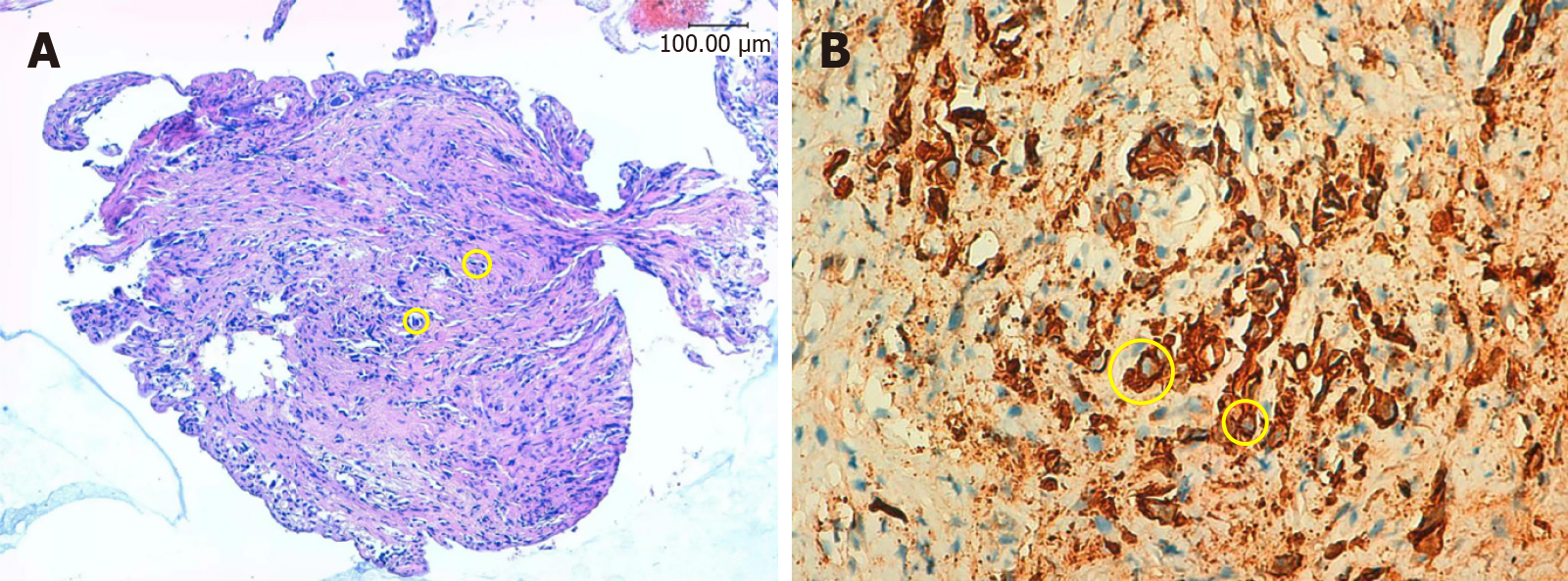

ERCP combined with choledochoscopy was performed, demonstrating the stenoses in the left and right hepatic ducts within the hilar region, the common hepatic duct, and the proximal common bile duct. Choledochoscopy revealed mild local congestion in the distal common bile duct, with no evidence of ulceration or neoplasm. A stenosis with reddened and slightly rough mucosa was identified in the upper section of the common bile duct (Figure 2). Six tissue samples were collected from the stenotic area using a disposable sterile pancreaticobiliary biopsy forceps for pathological analysis. Following dilation of the stenosis with a biliary dilation catheter, a plastic stent (8.5 Fr × 15 cm) was placed across the stenosis. The proximal end of the stent was positioned in the left hepatic duct, and its distal end in the duodenum (Figure 3). Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the common bile duct (Figure 4). Immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: Cytokeratin (CK) (+), vimentin (-), caudal-type homeobox protein 2 (-), CD10 (-), Ki-67 (50%+), and carcinoembryonic antigen (+). A possible diagnosis of bile duct metastasis originating from gastric cancer with biliary obstruction was considered.

Following biliary stent placement, the patient’s symptoms were relieved, accompanied by a remarkable improvement in liver function tests. At the three-month follow-up after discharge, his liver function tests normalized, and he reported no significant abdominal discomfort. Subsequently, he was treated with oxaliplatin in combination with raltitrexed. Unfortunately, at the last telephone visit with his wife, the patient passed away on March 5, 2025 (Table 1).

| Time | Symptoms | Interventions | Outcomes |

| August 2022 | Epigastric pain | Gastroscopy indicated the mass with a size of 6 cm × 4.8 cm × 1.5 cm located at the gastric body near to gastric angle | Pathological examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma |

| September 2022 | - | Exploratory laparotomy indicated liver metastasis | Completed 8 cycles of sindilizumab in combination with XELOX |

| April 2023 | - | Total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis | Pathological examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach with some signet ring cells |

| May 2023-November 2023 | - | Sindilizumab combined with capecitabine | No abdominal pain. No recurrent tumor is identified on the follow-up PET/CT scan |

| December 2023 | Right upper abdominal discomfort and jaundice with scleral icterus | Radiologic imaging showed high biliary obstruction | Jaundice and biochemical markers progressively worsened |

| Oral hepatoprotective medications | |||

| PTCD and PTGD | |||

| January 2024 | - | ERCP combined with choledochoscopy | Liver function tests normalized, and abdominal discomfort was relieved. Pathological examination with immunohistochemical staining showed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of common bile duct. |

| Endoscopic bile duct biopsy | |||

| Placement of a biliary stent | |||

| May 2024-August 2024 | - | Oxaliplatin combined with raltitrexed | The patient rigorously complied with the prescribed chemotherapy regimen and exhibited no abdominal pain, fever, or jaundice throughout the therapeutic course |

| March 5, 2025 | - | - | Died |

Gastric cancer commonly tends to metastasize to the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneum[4]. According to the anatomical database of the Japanese Society of Pathology, a total of 31266 cases with gastric cancer were confirmed by autopsy during a period from 2005 to 2014, of whom 8.5% had liver metastasis and 1.8% gallbladder and extrahepatic bile duct metastasis[5]. Thus, it should be readily estimated that hilar bile duct metastasis should be extremely rare, despite the lack of accurate data. To the best of our knowledge, only a few cases with a definite diagnosis of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer were available[5-7]. Nakamura et al[6] proposed that the diagnosis of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer could be considered, if all of the following criteria were met: (1) Gastric cancer and cholangiocarcinoma specimens were similar in histological differentiation patterns, mainly including poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma; (2) Gastric cancer and cholangiocarcinoma have similar immunohistochemical staining results, demonstrating overlapping patterns of CK7 and CK20; and (3) In primary gastric lesion, the tumor infiltrated from the mucosal layer to the serosal layer, but in bile duct metastasis lesion, the biliary mucosal epithelium was largely normal without high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma in situ detected. To further clarify the diagnosis, we performed a retrospective immunohistochemical analysis on the bile duct biopsy tissue, and the tissue exhibited a CK7-/CK20- phenotype with positive Villin expression. As known, CK7/CK20 immunohistochemical staining is commonly used to distinguish primary cholangiocarcinoma (typically CK7+/CK20-) from metastatic gastric carcinoma (often CK7+/CK20+), but poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinomas, particularly signet ring cell carcinomas, frequently exhibit CK20 negative expression[8]. Despite atypical CK7-/CK20- immunophenotype, the diagnosis of metastatic gastric cancer can be supported by integrating clinical, radiological, and pathological evidence. In our case, the diagnosis of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer was based on four key findings: (1) The patient was first diagnosed with poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma, followed by a diagnosis of poorly differentiated bile duct adenocarcinoma; (2) Pathological examination revealed an intact bile duct mucosal epithelium, ruling out primary biliary origin; (3) Imaging examinations revealed circumferential wall thickening of the bile duct, which is typically a direct radiological sign of metastasis; and (4) Comprehensive radiographic evaluation did not identify any potential primary malignancy originating from other organs. Unfortunately, gross specimens of the bile duct could not be obtained in our patient, because he did not perform repeated surgery nor autopsy.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the best imaging method to diagnose primary cholangiocarcinoma[9]. MRCP can reflect the degree and range of bile duct dilatation and its morphological characteristics. Primary cholangiocarcinoma is characterized as: (1) One side of the bile duct wall is thickened, leading to a sign of abrupt luminal truncation or residual root; and (2) The most obvious dilatation is located at the upstream of the lesion, like a soft vine[10]. By contrast, the bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer often appears as uniform, concentric, linear or band-like, and enhanced biliary wall thickening, and grows along the biliary wall[11]. In our case, MRCP showed that the stenosis of bile duct was concentric thickening without obvious mass limited to one side of the bile duct wall.

It is difficult to obtain an accurate pre-surgical pathological diagnosis of primary or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. In fact, some studies have shown that nearly 40% of the cases with suspected cholangiocarcinoma at the hepatic hilum underwent surgical resection without positive preoperative histological result[6]. A meta-analysis showed that conventional ERCP-guided bile duct brush cytology and intraductal biopsy had a low sensitivity of 45% and 48.1% for the diagnosis of malignant biliary obstructions, respectively[12]. Nevertheless, the current European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines endorse ERCP with choledochoscopy-guided biopsies as the diagnostic cornerstone for indeterminate biliary strictures[13], with a sensitivity of 72%-94% and a specificity of 87%-99% for histopathological confirmation[14-18]. Beyond that, previous studies reported that the sensitivity of ERCP with choledochoscopy-guided biopsies for diagnosing malignant biliary obstructions was up to 63.6%-88%[19,20]. In our patient, total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed prior to ERCP. In such cases, the success rate of therapeutic ERCP utilizing a conventional side-viewing duodenoscope is unsatisfactory due to altered anatomy, including a long afferent limb, sharp angulation of the anastomosis, and an opposite direction of the papilla. Even with the adoption of relatively long and flexible colonoscopes or enteroscopes, ERCP remains technically challenging, achieving a success rate of only 33%-67%[21]. In our patient, therapeutic ERCP was successfully performed with colonoscopy, and biliary tissue was obtained through choledochoscopy with a positive pathological diagnosis, which was particularly commendable. Therefore, for patients with a history of total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction who require endoscopic biliary plastic stent placement, our protocol is as follows. First, the length of stricture is precisely measured to select appropriate size of a stent, ensuring adequate relief of biliary obstruction, while minimizing the risk of stent migration. Second, during its deployment, the stent is advanced gradually under continuous fluoroscopic guidance, and excessive force is avoided, thereby reducing the risk of perforation. Patients are advised to be followed with laboratory evaluation of liver function and radiographic imaging one month after discharge to confirm stent patency and position.

Biliary tract metastasis from gastric cancer is a rare yet highly aggressive pattern of dissemination. Its underlying mechanisms involve complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment, immune escape mechanisms, and molecular reprogramming. The tumor immune microenvironment adopts an immunosuppressive phenotype characterized by the recruitment of regulatory T cells, tumor-associated macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which secrete inhibitory cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β and interleukin-10[22]. Immunotherapy has demonstrated strong efficacy and tolerable toxicity compared with traditional treatments, leading to growing interest in novel therapeutic strategies for gastric cancer. Nivolumab, a programmed death-1 inhibitor, is a monoclonal antibody approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer in 2014[23]. Another critical molecular target is HER2, a member of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family involved in cancer cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. HER2 overexpression/HER2 amplification is observed in approximately 6%-35% of gastric cancer cases[24]. Trastuzumab, as the first targeted drug for HER2-amplified gastric cancer, effectively inhibits tumor cell proliferation and metastasis. The molecular mechanisms driving gastric cancer metastasis involve multiple signaling pathways, such as transforming growth factor-β/mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 6, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription, and nuclear factor kappa-B[25]. However, due to the rarity of biliary tract metastasis from gastric cancer, the specific molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain insufficiently explored and require further investigation.

The probability of bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer should not be neglected in patients presenting with progressive jaundice following curative resection of gastric carcinoma. However, it is often difficult to distinguish primary cholangiocarcinoma from bile duct metastasis from gastric cancer. In such cases, the biopsy of bile duct tissue is required to rule out metastasis and to guide treatment selection. In the future, large-scale studies are necessary to evaluate the sensitivity of ERCP combined with choledochoscopy in patients suspected of having bile duct tumor.

| 1. | Khoo S, Do NDT, Kongkam P. Efficacy and safety of EUS biliary drainage in malignant distal and hilar biliary obstruction: A comprehensive review of literature and algorithm. Endosc Ultrasound. 2020;9:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chu D, Adler DG. Malignant biliary tract obstruction: evaluation and therapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:1033-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Poletto E, Ruzzenente A, Turri G, Conci S, Ammendola S, Luchini C, Scarpa A, Guglielmi A. Surgical treatment of ductal biliary recurrence of poorly cohesive gastric cancer mimicking primary biliary tract cancer: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022:rjac132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sirody J, Kaji AH, Hari DM, Chen KT. Patterns of gastric cancer metastasis in the United States. Am J Surg. 2022;224:445-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Takaichi S, Sakai K, Hatanaka N, Hirao T, Osawa H, Yamasaki Y. [A case of gastric cancer with bile duct metastasis and recurrence at the 7th year after surgery]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2018;79:90-95. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Nakamura S, Kuriyama N, Hayasaki A, Fujii T, Iizawa Y, Murata Y, Tanemura A, Kishiwada M, Sakurai H, Yuasa H, Hayashi A, Mizuno S. [A case of resection of gastric cancer bile duct metastasis that was difficult to differentiate from hilar cholangiocarcinoma]. Nihon Shokaki Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2023;56:154-164. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Vaz K, Luber RP, McLean C, Gerstenmaier JF, Roberts SK. Gastric adenocarcinoma causing biliary obstruction without ductal dilatation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shima T, Arita A, Sugimoto S, Takayama S, Kawaguchi N, Imai Y, Kitahara T, Maeda T, Okuda J. Simultaneous colonic metastasis of advanced gastric cancer: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2023;9:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jhaveri KS, Hosseini-Nik H. MRI of cholangiocarcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:1165-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liang C, Mao H, Wang Q, Han D, Li Yuxia L, Yue J, Cui H, Sun F, Yang R. Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in malignant obstructive jaundice. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61:383-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee J, Gwon DI, Ko GY, Kim JW, Sung KB. Biliary intraductal metastasis from advanced gastric cancer: radiologic and histologic characteristics, and clinical outcomes of percutaneous metallic stent placement. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:1649-1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Navaneethan U, Njei B, Lourdusamy V, Konjeti R, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Comparative effectiveness of biliary brush cytology and intraductal biopsy for detection of malignant biliary strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:168-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Pouw RE, Barret M, Biermann K, Bisschops R, Czakó L, Gecse KB, de Hertogh G, Hucl T, Iacucci M, Jansen M, Rutter M, Savarino E, Spaander MCW, Schmidt PT, Vieth M, Dinis-Ribeiro M, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic tissue sampling - Part 1: Upper gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary tracts. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53:1174-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun X, Zhou Z, Tian J, Wang Z, Huang Q, Fan K, Mao Y, Sun G, Yang Y. Is single-operator peroral cholangioscopy a useful tool for the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesion? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:79-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Korrapati P, Ciolino J, Wani S, Shah J, Watson R, Muthusamy VR, Klapman J, Komanduri S. The efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E263-E275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Badshah MB, Vanar V, Kandula M, Kalva N, Badshah MB, Revenur V, Bechtold ML, Forcione DG, Donthireddy K, Puli SR. Peroral cholangioscopy with cholangioscopy-directed biopsies in the diagnosis of biliary malignancies: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:935-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Oliveira PVAG, de Moura DTH, Ribeiro IB, Bazarbashi AN, Franzini TAP, Dos Santos MEL, Bernardo WM, de Moura EGH. Efficacy of digital single-operator cholangioscopy in the visual interpretation of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3321-3329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kulpatcharapong S, Pittayanon R, J Kerr S, Rerknimitr R. Diagnostic performance of different cholangioscopes in patients with biliary strictures: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2020;52:174-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pereira P, Santos S, Morais R, Gaspar R, Rodrigues-Pinto E, Vilas-Boas F, Macedo G. Role of Peroral Cholangioscopy for Diagnosis and Staging of Biliary Tumors. Dig Dis. 2020;38:431-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Manta R, Frazzoni M, Conigliaro R, Maccio L, Melotti G, Dabizzi E, Bertani H, Manno M, Castellani D, Villanacci V, Bassotti G. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the evaluation of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective, cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1569-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shao XD, Qi XS, Guo XZ. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with double balloon enteroscope in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy: A meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:150-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li GQ, Wan YX, Jiao AL, Jiang K, Cui GY, Tang JX, Yu SM, Hu ZG, Zhao SF, Yi ZJ, Long LF, Yang Y, Cui XH, Qu CR. Breaking Boundaries: Chronic Diseases and the Frontiers of Immune Microenvironments. Med Research. 2025;1:62-102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Mou P, Ge QH, Sheng R, Zhu TF, Liu Y, Ding K. Research progress on the immune microenvironment and immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1291117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim M, Seo AN. Molecular Pathology of Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2022;22:273-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yan Y, Wang LF, Wang RF. Role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9717-9726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/