Published online Sep 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.108348

Revised: May 23, 2025

Accepted: July 21, 2025

Published online: September 27, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 0.6 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the intestinal tract that can alternate between disease phases and remission. Currently, endoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis of CD and evaluation of its activity and complica

A 15-year-old female presented with recurrent right lower quadrant abdominal pain that had persisted for 2 weeks. Initial GIUS and computed tomography revealed significant edema of the appendix and ascending colon wall, thickening, and multiple lymphadenopathies of the mesentery. Clinicians suspected appen

CD should be suspected with persistent right lower quadrant abdominal pain. GIUS is essential for initial evaluation, before the confirmatory endoscopy, to assess CD-typical signs like bowel edema and thickening.

Core Tip: Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. In recent years the incidence of CD has increased. Gastrointestinal ultrasound (GIUS) features in patients with CD are specific and include segmental bowel wall thickening, mesenteric edema and thickening, and bowel stenosis. When the identifications of these features are combined with clinical symptoms, a high diagnostic accuracy can be achieved. The use of GIUS for the initial diagnosis and evaluation of disease activity and complications in patients with CD is increasingly common.

- Citation: Wang WQ, Yang JP, Dong JW, Chen YB. Misdiagnosis of Crohn’s disease as appendicitis: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(9): 108348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i9/108348.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i9.108348

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract and can affect individuals of all ages; although, the peak incidence occurs between the ages of 15 years and 25 years[1]. CD is associated with reduced dietary fiber intake, smoking (including secondhand smoke), dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, and immune system deficiencies[2]. It has an insidious onset and can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with the terminal ileum and colon being the most involved sites.

Typical clinical symptoms of CD include right lower quadrant abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and hematochezia. Approximately 50% of cases exhibit extraintestinal manifestations such as skin disorders and arthritis. One-third of CD patients develop complications such as fistulas, intestinal stenosis, and abscesses. When abscesses develop, patients may present with a high fever.

To diagnose CD several modalities are employed to ensure accurate disease management. Typical laboratory abnormalities in CD include anemia, thrombocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein levels[3]. The gold standard for diagnosing CD is endoscopy followed by biopsy[4]. Segmental inflammatory lesions and longitudinal or serpiginous ulcers are typical endoscopic features. When ulcers intermingle with nodular edematous mucosa, a cobblestone appearance is observed[5].

Recently, gastrointestinal ultrasound (GIUS) has become more common for the initial imaging of patients with CD. GIUS findings for CD are relatively specific and include segmental bowel wall thickening, mesenteric edema and thickening, polyp formation, and luminal stenosis. GIUS has several advantages including no radiation exposure and high repeatability in intestinal disease diagnosis. As the primary imaging modality for diagnosis and follow-up, espe

Cases of CD involving the appendix are uncommon. Mostyka et al[7] retrospectively analyzed 100 ileocolic CD specimens and found that only 10 had inflammation around the appendix. The clinical manifestations of CD in the ileocecal region are similar to acute appendicitis. Both will present as right lower abdominal pain. Moreover, differential diagnosis based on clinical symptoms and imaging is difficult when there are no signs of intestinal jumping edema or complications like stenosis[8].

The purpose of this case report was to summarize the experience of misdiagnosing ileocecal CD as appendicitis and to emphasize the important role of GIUS in the follow-up of CD.

A 15-year-old female presented with gradually intensifying right lower quadrant abdominal pain that had begun 2 weeks prior to presentation, without any obvious cause and accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and hematochezia.

In the previous 2 months, the patient had experienced recurrent episodes of right lower quadrant abdominal pain without an obvious cause. The pain progressively worsened but would be slightly alleviated with rest. One month prior, GIUS had revealed appendiceal fecalith, significant edema, thickening of the appendix and ascending colon wall with surrounding exudation, and multiple lymphadenopathies of the mesentery. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) had then confirmed these findings. As a result, the clinical diagnosis of “acute appendicitis with localized peritonitis” was made and a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed. During the operation the appendix had been found to be enlarged to 1 cm in diameter and 8 cm in length with congestion and edema; a small amount of purulent exudate was also noted around it. The mesenteric lymph nodes of the surrounding intestine had been noted to be significantly enlarged and the cecum to have marked edema. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was simple appendicitis. Throughout the course of this case, the patient did not experience fever, chest tightness, nor chest pain.

The patient was previously healthy and denied any history of trauma, allergies, or infectious diseases.

There was no significant personal or family history of medical conditions.

The patient’s vital signs were stable: Temperature was 36.1 °C; heart rate was 136 beats per minute, regular, and with no murmurs; and blood pressure was 91/66 mmHg. The patient was conscious and alert. Breath sounds were clear in both lungs without any dry or wet rales. The abdomen was soft and flat, with tenderness in the right lower quadrant. The liver and spleen were not palpable below the costal margin. Bowel sounds occurred 5 times per minute. There was no edema in the lower extremities.

The following laboratory parameters were abnormal: Platelet count: 447.0 × 109/L (reference range: 125.0-350.0 × 109/L); hemoglobin: 82.0 g/L (reference range: 120.0-140.0 g/L); and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: 79.1 mg/L (reference range: 0.0-10.0 mg/L). Other biochemical markers and routine blood tests did not reveal any significant abnormalities.

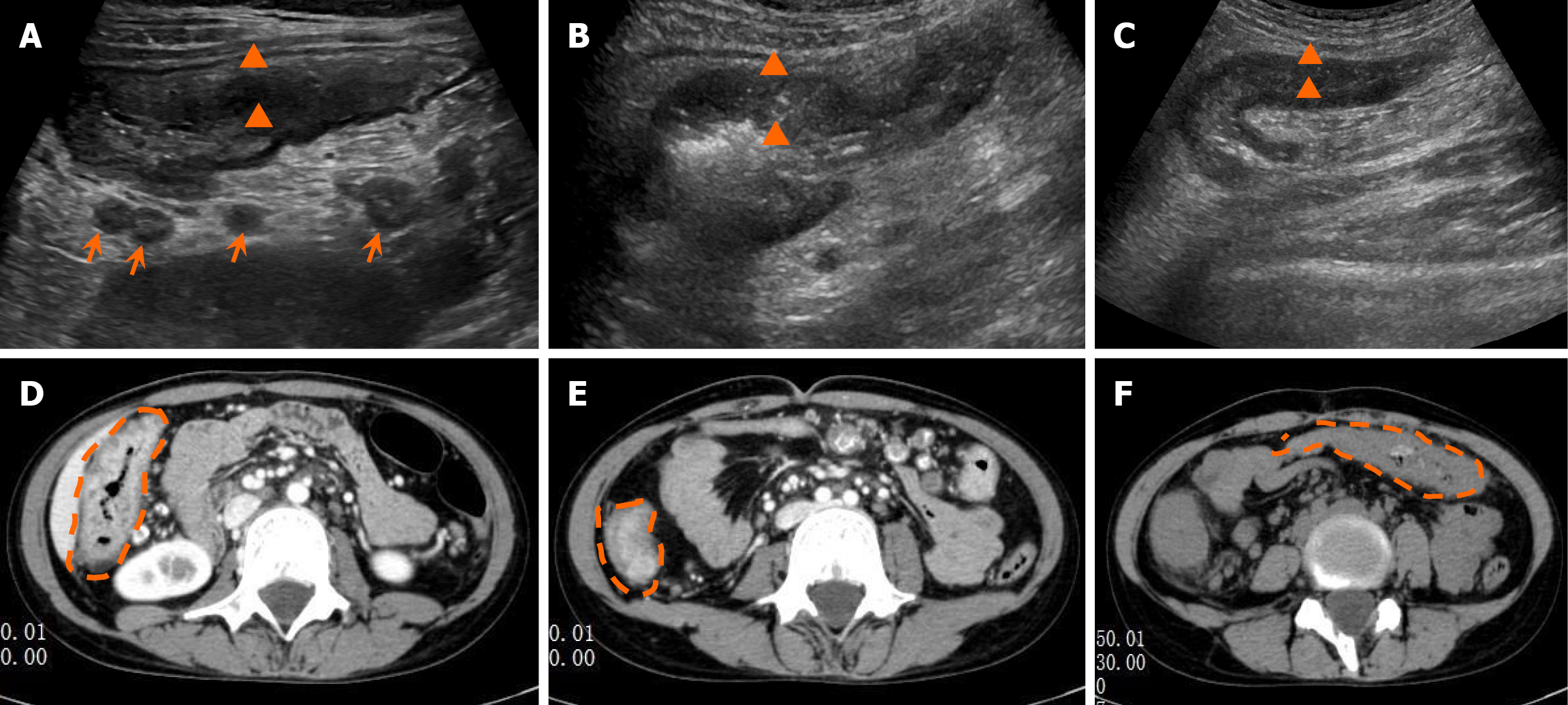

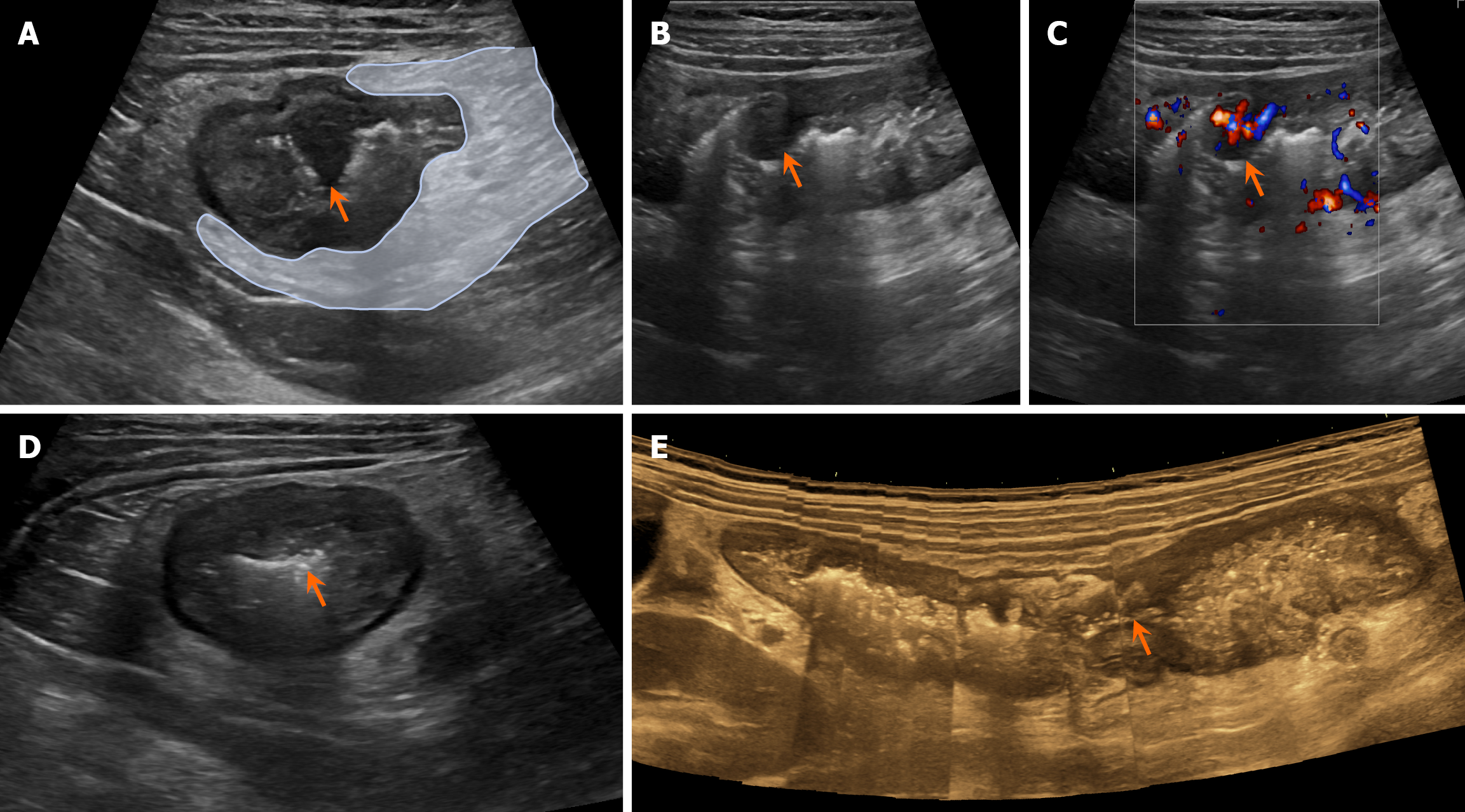

Postoperative recurrence GIUS revealed significant edema and thickening of the bowel wall in the terminal ileum, cecum, ascending colon, and splenic flexure of the transverse colon (Figure 1A-C). Non-contrast CT confirmed an edematous and thickened terminal ileum, cecum, ascending colon, and splenic flexure of the transverse colon (Figure 1D-F). There was a nodular protrusion into the lumen of the ascending colon (Figure 2A-C) with local luminal stenosis (Figure 2D and E). The surrounding mesenteric tissue showed edema and thickening with encasement (Figure 2A). CD was considered on the basis of these findings.

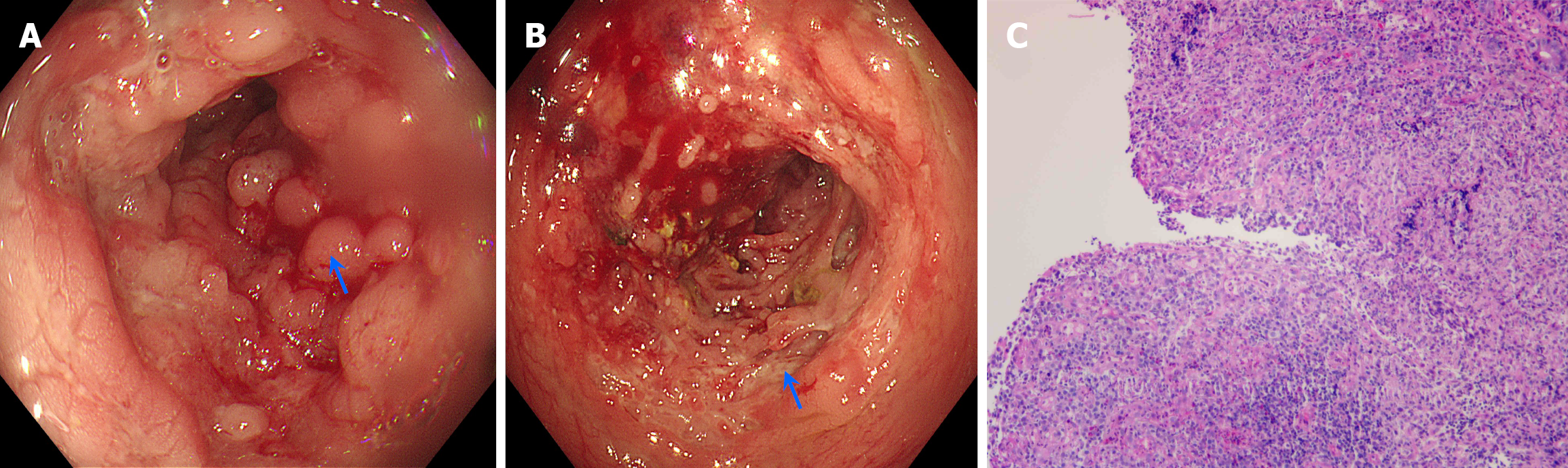

Colonoscopy revealed mucosal hyperplasia, elevation at the terminal ileum, and patchy hyperplasia of the mucosa in the ileocecal region, colon of the hepatic flexure, ascending colon, and transverse colon with a cobblestone appearance (Figure 3A). Longitudinal or serpiginous ulcerative lesions, which were friable and prone to bleeding, were visible between the mucosa (Figure 3B). The lesions were segmental and distributed in a skip pattern, whereas the remaining intestinal mucosa appeared normal without congestion, erosion, or ulcers. No abnormal hyperplasia was observed. Biopsies were taken from different sites of the intestine. Pathological results revealed chronic inflammation of the mucosa in the ileocecal region, ascending colon, and transverse colon as well as lymphocytic aggregation and granuloma for

On the basis of the colonoscopic findings, histopathological results of the biopsies, GIUS features, and clinical symptoms, the final diagnosis was established as CD.

After a definitive diagnosis was established, the patient was placed on a semiliquid diet and received intravenous methylprednisolone (40 mg/day) for anti-inflammatory treatment. After 1 week the patient received oral methylprednisolone tablets (32 mg/day) for another 3 days. The patient’s abdominal pain significantly improved.

The patient’s vital signs were stable with no abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, or hematochezia. The abdomen was soft and without tenderness, and bowel sounds were heard 5 times per minute. The patient was discharged with instruc

In recent years, the incidence of CD has significantly increased globally[6], and early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for ensuring effective treatment. Similar to the clinical symptoms of CD, many intestinal diseases can present with right lower quadrant pain, such as appendicitis, ulcerative colitis, and colon cancer. However, each of these diseases has relatively specific characteristics. For example, appendicitis typically presents with migratory right lower quadrant abdominal pain, tenderness, and rebound tenderness at McBurney’s point. However, it is often not accompanied by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and changes in bowel habits[9]. Ulcerative colitis primarily affects the rectum and colon with clinical manifestations of mucopurulent bloody stools and tenesmus[10]. Colorectal cancer commonly occurs in middle-aged and elderly populations and may appear on ultrasound as a structure with a disorganized bowel wall and a mass-like echoic appearance[11]. When the right lower quadrant pain is suspected to be caused by an intestinal disease, clinicians must carefully distinguish and meticulously evaluate patients through epidemiology, imaging, blood tests, and timely endoscopy.

In our case, the patient’s clinical symptoms and initial imaging findings from GIUS and CT were insufficient to diagnose CD. However, the presence of anemia in the patient was indicative of CD. Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding is observed in CD due to intestinal ulcers and nutrient malabsorption, which can lead to anemia. However, acute appen

Currently, endoscopy remains the gold standard for assessing the severity of CD and evaluating treatment response[1]. However, it is invasive and may not be well tolerated by patients, especially adolescents. GIUS is a cross-sectional imaging modality and has many benefits in the management of CD due to its low cost, repeatability, and lack of radiation exposure. Numerous studies have demonstrated that GIUS is comparable in sensitivity and specificity to enteric CT and magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing CD, assessing disease activity, and detecting complications when performed by experienced operators[2,12,13].

The normal bowel wall appears as a five-layer structure on an ultrasound. It consists of the following layers: A hyperechoic mucosal-lumen interface; the submucosa; the serosa; the hypoechoic mucosal layer; and the muscular layer[14]. The representative and effective signs of CD on GIUS are bowel wall thickness (BWT), vascularity and layering structure, presence of mesenteric inflammatory fat, motility of the bowel, and enlargement of mesenteric lymph nodes[15]. Among these indicators, BWT is the most reliable indicator. The BWT is obtained by measuring the bowel wall in both the longitudinal and transverse planes multiple times with a high-frequency probe and calculating the average value. The overall sensitivity of BWT for diagnosing CD can reach 0.85 (95%CI: 83%-87%), and the overall specificity can reach 98% (95%CI: 95%-99%)[16]. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and European Society of Gastroin

GIUS has several advantages in dynamically evaluating CD activity. It is convenient and highly repeatable, and it matches endoscopic assessment in diagnostic accuracy. Sævik et al[18] developed a simple ultrasound scoring criterion using BWT and bowel wall flow to predict CD activity. They used the simplified endoscopic activity score for CD as a reference standard. In the validation cohort their model had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.92. Allocca et al[19,20] retrospectively analyzed BWT and bowel wall flow for predicting the endoscopic activity of CD and prospectively validated it with an accuracy of 0.80. Kucharzik et al[21] monitored disease activity in patients with CD after pharmacological treatment with GIUS and reported significant differences in ultrasound parameters before and after treatment.

CD is a long-term chronic condition, and intestinal stenosis is a major complication of the disease. In this case, panoramic ultrasound imaging clearly showed the internal diameter and length of the intestinal stenosis. This is difficult to achieve with cross-sectional CT. Lu et al[22] observed that the specificity of GIUS for diagnosing intestinal stenosis was 86%-100%. Intestinal stenosis is caused by fibrosis of the bowel wall, and studies have shown that the mean strain ratio of fibrotic stenotic bowel segments is higher than that of nonfibrotic ones. Ultrasound elastography has the ability to assess intestinal wall fibrosis and offers a new diagnostic approach for bowel stenosis[23].

GIUS can serve as an alternative to endoscopy for assessing postoperative recurrence in patients with CD. When complications occur, approximately 70% of patients with CD require surgery, and 30% of these patients experience recurrence after surgery[24]. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization recommends that patients with CD who have undergone surgery due to complications should receive follow-up endoscopy within 6-12 months after surgery to detect recurrence[16]. Two meta-analyses by Barchi et al[25] and Rispo et al[26] evaluated the effectiveness of GIUS in detecting postoperative recurrence and reported an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93 and an accuracy of 0.875.

In this study our patient was evaluated by GIUS twice. GIUS detected segmental edema and thickening of the bowel wall and mesentery and clearly visualized intestinal polyps. The diagnostic information obtained was far more detailed than with CT, and these details were particularly helpful for diagnosing CD.

A thorough full abdominal GIUS examination detecting the typical signs of segmental bowel wall edema, stenosis, and polyp formation combined with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia, can accurately diagnose CD.

The authors express gratitude to the staff of the Nanxun People’s Hospital for their assistance. Without their efforts in interprofessional collaboration for data collection and patient treatment, this case report would not have been possible.

| 1. | Cushing K, Higgins PDR. Management of Crohn Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:69-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1979] [Article Influence: 219.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (113)] |

| 3. | Hanauer SB. Targeting Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;390:2742-2744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1347] [Cited by in RCA: 1580] [Article Influence: 112.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roda G, Chien Ng S, Kotze PG, Argollo M, Panaccione R, Spinelli A, Kaser A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Crohn's disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu Y, Ma Y, Cui Z, Pan Y, Diao J. Bibliometric analysis of Crohn's disease in children, 2014-2024. Front Pediatr. 2025;13:1515251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mostyka M, Fulmer CG, Hissong EM, Yantiss RK. Crohn Disease Infrequently Affects the Appendix and Rarely Causes Granulomatous Appendicitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1703-1706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Malvar G, Peric M, Gonzalez RS. Interval appendicitis shows histological differences from acute appendicitis and may mimic Crohn disease and other forms of granulomatous appendicitis. Histopathology. 2022;80:965-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Scheijmans JCG, Haijanen J, Flum DR, Bom WJ, Davidson GH, Vons C, Hill AD, Ansaloni L, Talan DA, van Dijk ST, Monsell SE, Hurme S, Sippola S, Barry C, O'Grady S, Ceresoli M, Gorter RR, Hannink G, Dijkgraaf MG, Salminen P, Boermeester MA. Antibiotic treatment versus appendicectomy for acute appendicitis in adults: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;10:222-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Voelker R. What Is Ulcerative Colitis? JAMA. 2024;331:716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Willyard C. The Colon Cancer Conundrum. Nature. 2021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Conti CB, Giunta M, Gridavilla D, Conte D, Fraquelli M. Role of Bowel Ultrasound in the Diagnosis and Follow-up of Patients with Crohn's Disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:725-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Panés J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, Gisbert JP, Martínez de Guereñu B, Mendoza JL, Paredes JM, Quiroga S, Ripollés T, Rimola J. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:125-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Voogd FAE, Verstockt B, Maaser C, Gecse KB. Point-of-care intestinal ultrasonography in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:209-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Goodsall TM, Jairath V, Feagan BG, Parker CE, Nguyen TM, Guizzetti L, Asthana AK, Begun J, Christensen B, Friedman AB, Kucharzik T, Lee A, Lewindon PJ, Maaser C, Novak KL, Rimola J, Taylor KM, Taylor SA, White LS, Wilkens R, Wilson SR, Wright EK, Bryant RV, Ma C. Standardisation of intestinal ultrasound scoring in clinical trials for luminal Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:873-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reinisch W, Stoker J, Taylor SA, Baumgart DC, Danese S, Halligan S, Marincek B, Matos C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Rimola J, Rogler G, van Assche G, Ardizzone S, Ba-Ssalamah A, Bali MA, Bellini D, Biancone L, Castiglione F, Ehehalt R, Grassi R, Kucharzik T, Maccioni F, Maconi G, Magro F, Martín-Comín J, Morana G, Pendsé D, Sebastian S, Signore A, Tolan D, Tielbeek JA, Weishaupt D, Wiarda B, Laghi A. Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:556-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kucharzik T, Tielbeek J, Carter D, Taylor SA, Tolan D, Wilkens R, Bryant RV, Hoeffel C, De Kock I, Maaser C, Maconi G, Novak K, Rafaelsen SR, Scharitzer M, Spinelli A, Rimola J. ECCO-ESGAR Topical Review on Optimizing Reporting for Cross-Sectional Imaging in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:523-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 18. | Sævik F, Eriksen R, Eide GE, Gilja OH, Nylund K. Development and Validation of a Simple Ultrasound Activity Score for Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Allocca M, Craviotto V, Bonovas S, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Fiorino G, Danese S. Predictive Value of Bowel Ultrasound in Crohn's Disease: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e723-e740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Allocca M, Craviotto V, Dell'Avalle C, Furfaro F, Zilli A, D'Amico F, Bonovas S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Fiorino G, Danese S. Bowel ultrasound score is accurate in assessing response to therapy in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, Börner N, Rössler A, Rath S, Maaser C; TRUST study group. Use of Intestinal Ultrasound to Monitor Crohn's Disease Activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:535-542.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lu C, Rosentreter R, Delisle M, White M, Parker CE, Premji Z, Wilson SR, Baker ME, Bhatnagar G, Begun J, Bruining DH, Bryant R, Christensen B, Feagan BG, Fletcher JG, Jairath V, Knudsen J, Kucharzik T, Maaser C, Maconi G, Novak K, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Wilkens R, Rieder F; Stenosis Therapy and Anti‐Fibrotic Research (STAR) consortium. Systematic review: Defining, diagnosing and monitoring small bowel strictures in Crohn's disease on intestinal ultrasound. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59:928-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vestito A, Marasco G, Maconi G, Festi D, Bazzoli F, Zagari RM. Role of Ultrasound Elastography in the Detection of Fibrotic Bowel Strictures in Patients with Crohn's Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:646-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Crocco S, Martelossi S, Giurici N, Villanacci V, Ventura A. Upper gastrointestinal involvement in paediatric onset Crohn's disease: prevalence and clinical implications. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Barchi A, D'Amico F, Zilli A, Furfaro F, Parigi TL, Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S, Dal Buono A, Allocca M. Recent advances in the use of ultrasound in Crohn's disease. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2023;20:1119-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rispo A, Imperatore N, Testa A, Nardone OM, Luglio G, Caporaso N, Castiglione F. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography in the Detection of Postsurgical Recurrence in Crohn's Disease: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:977-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/