Published online Jul 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106919

Revised: April 7, 2025

Accepted: May 28, 2025

Published online: July 27, 2025

Processing time: 134 Days and 23.8 Hours

Bile spillage occurs more frequently in patients with incidental gallbladder carcinoma (iGBC) and may be associated with poor survival due to presumed high risk of peritoneal seeding.

To investigate the impact of bile spillage during primary surgery on the survival of patients with iGBC.

Medical records of patients with iGBC diagnosed between 2000 and 2019 in 27 Dutch secondary centers and 5 tertiary centers were retrospectively reviewed. Patient medical records were assessed. Predictors for overall survival (OS) were determined using multivariable Cox regression.

Of the 346 included patients with iGBC, 138 (39.9%) had bile spillage, which was associated with higher American Society of Anesthesiologists classification (P = 0.020), cholecystitis (P < 0.001), higher tumor stage (P = 0.005), and non-radical resection (P < 0.001). Bile spillage was associated with poor OS [hazard ratio = 1.97, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.48–2.63, P < 0.001] with a median OS of 12 months (95%CI: 7-18 months) vs 34 months (95%CI: 14–55 months, P < 0.001). In multivariable analysis, spillage was not an independent prognostic factor for survival (hazard ratio = 1.21, 95%CI: 0.84-1.74, P = 0.313).

Although bile spillage correlates with prognostic factors, it lacks independent prognostic significance for survival. Patients with an indication for additional treatment should be promptly referred to a specialized hepatopancreatobiliary center, irrespective of whether bile spillage has occurred.

Core Tip: In this retrospective cohort study, the relationship between bile spillage and survival in patients with incidental gallbladder carcinoma was analyzed in 32 Dutch hospitals. Bile spillage was associated with adverse prognostic factors, namely higher age, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, T stage, and non-radical resection. Unlike those other factors, bile spillage was not an independent predictor for survival in multivariable analysis. In our cohort bile spillage was linked to localized rather than peritoneal reoccurrence as described in existing literature. Patients with an indication for additional treatment should be referred to a specialized hepatopancreaticobiliary center, irrespective of whether bile spillage has occurred.

- Citation: Dooren MV, de Savornin Lohman EA, van der Post RS, Hoogwater FJ, van den Boezem PB, Groot Koerkamp B, Erdmann JI, de Reuver PR. Bile spillage in incidental gallbladder cancer is not an independent predictor for survival: A multi-institute retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(7): 106919

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i7/106919.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106919

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract[1]. The overall prognosis is poor with a 5-year survival of around 10%[2]. Up to 70% of GBC cases in Western populations are diagnosed incidentally (iGBC) after cholecystectomy for presumed benign gallbladder disease[3,4]. Curation can be achieved in patients with localized disease by en bloc resection of the gallbladder bed and hepatoduodenal lymph nodes. Disseminated disease, which is frequently not discovered until re-exploration, precludes radical re-resection. Identifying patients at risk for disseminated disease is paramount in clinical decision-making as it may influence the decision to perform a staging laparoscopy or might prevent futile exploration[5]. The factors predicting disseminated disease have been studied to a limited extent[4,6,7].

A potential risk factor for disseminated disease is bile spillage. Although its relationship with port site recurrence has been regularly documented, its potential association with general disseminated diseases such as peritoneal metastases is less well defined[8-10]. It is hypothesized that bile spillage can be related to peritoneal carcinomatosis and therefore a worse prognosis[11]. A 2021 study of 93 patients with iGBC found that patients with major bile spillage had a 57% chance of developing peritoneal disease at 3 years postoperatively opposed to only 3% in patients without violation of the biliary tract[12]. Another study from the same year with 82 patients described that peritoneal disease developed in 24% of patients with bile spillage opposed to 4% without. However, no correlation was found between bile spillage and overall survival (OS)[13].

The present study aimed to evaluate the impact of bile spillage during primary surgery on the survival of patients with iGBC.

This retrospective multicenter cohort study received approval from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) ethical review board. An ethical approval waiver was granted by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the region Arnhem-Nijmegen (number 2019-5521). We adhered to the STROBE statement guidelines for reporting observational cohort studies[14]. Patients with GBC were identified using data from the NCR that captures information on all new malignancies in the country. The NCR is managed by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization and receives notifications of newly diagnosed patients through the automated pathological archive (PALGA)[15]. PALGA is the nationwide network and registry of histopathology and cytopathology in the Netherlands. Additional patient data are supplemented from the National Archive of Hospital Discharge Diagnosis. The study included patients diagnosed with iGBC between 2000 and 2019 from 27 secondary care centers and 5 tertiary care centers.

A local principal investigator was recruited for each center. They requested patient identification numbers of patients with GBC for their respective center through the NCR. The local principal investigator reviewed medical records of identified patients with GBC. Patients were only included when diagnosed with GBC perioperatively by the operating surgeon (with perioperative confirmation of suspicion by frozen section or postoperative conformation by histopathological examination) or postoperatively by histopathological examination. Information regarding the occurrence of bile spillage was extracted from surgery reports. Non-description of bile spillage was regarded as bile spillage not occurring. Patients were excluded from analysis when a full surgery report was not available. Demographic and clinical characteristics, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification[16], surgery details, pathology results, and survival data were collected using a standardized case report form in CastorEDC[17]. Data were pseudonymized for the lead investigators. When treated in multiple participating centers, medical records were combined per patient based on the patient-specific NCR identification number. OS was defined as the time from the date of index cholecystectomy to the date of death, irrespective of cause. Regional lymph nodes were defined as lymph nodes located along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, or portal vein in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual[18].

The primary endpoint was OS compared between patients with and without bile spillage. Secondary outcomes were the association of bile spillage with age, ASA classification, presence of cholecystitis, tumor stage, radical re-resection, and location of tumor recurrence.

Categorical variables were reported as counts with percentages and continuous variables as median values with corresponding interquartile ranges (IQR). Differences in baseline variables were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. The 3-year and 5-year survivals were defined as the percentage of patients that were alive at 3 years and 5 years, respectively, after diagnosis. Patients who were lost to follow-up or alive at the last date of follow-up were censored. Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival were obtained. OS was compared between patient groups using log-rank testing. Cox regression analysis was used to identify predictive factors for survival, using backwards logistical regression to account for multicollinearity and the number of included covariates. Covariates were selected based on the literature and were entered into the multivariable model when statistically relevant (P < 0.1) on univariable analysis. Missing data were determined to be ‘missing at random’ (unrelated to the outcome, potentially related to other parameters), and complete case analysis was used to assess covariates. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests of significance were two-tailed. Statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 25.0 statistical package (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States).

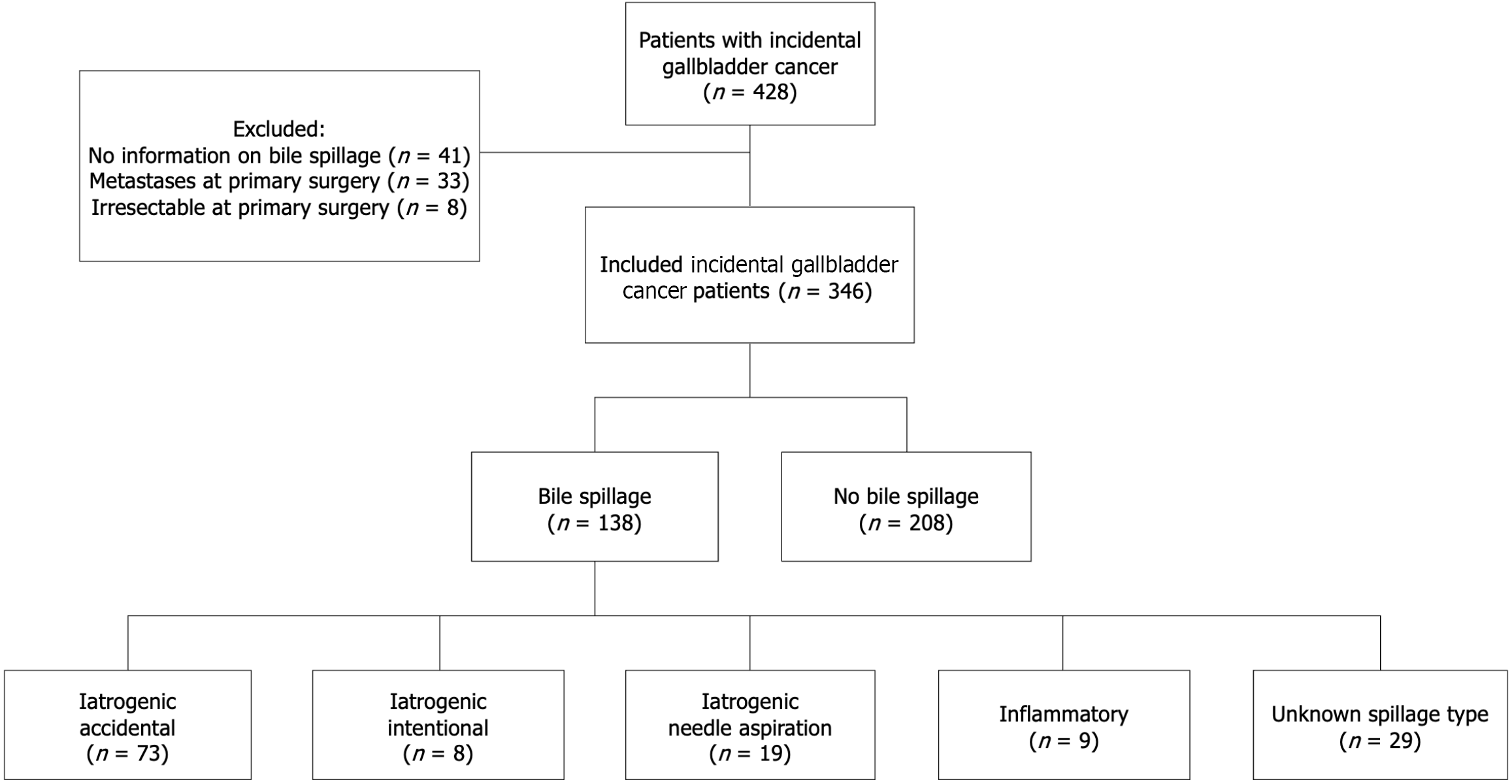

In total 428 patients with iGBC were analyzed. Among them 82 patients were excluded: 33 patients due to metastases at primary surgery; 8 patients due to irresectability at primary surgery; and 41 patients due to unavailability of information on the occurrence of bile spillage in patient medical records. Of the 346 included patients, the operation report of 138 (39.9%) mentioned bile spillage during initial cholecystectomy. Iatrogenic gallbladder injury was described in 100 patients (72.5%), of which 73 were accidental occurrences. Eight were due to intentional surgical intervention (such as subtotal cholecystectomy) and 19 were due to needle aspiration. In 9 patients (6.5%) bile spillage occurred due to inflammatory perforation. In 29 patients (21.0%) the exact circumstances of bile spillage could not be derived from the surgery report (Figure 1).

Of the 346 included patients, 306 (88%) underwent primary surgery in a secondary care center, and 40 patients underwent surgery in a tertiary care center. The median age at diagnosis was 73 years (IQR: 65-80 years) in patients with bile spillage and 67 years (IQR: 56-74 years) in patients without bile spillage (P < 0.001). A higher proportion of patients with bile spillage had an ASA classification of III/IV [31.9% (44/138) vs 21.2% (44/208), P = 0.020] (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Bile spillage (n = 138) | No bile spillage (n = 208) | P value |

| Age at diagnosis > 65 years | 104 (75.4) | 115 (55.3) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 86 (62.3) | 132 (63.5) | 0.829 |

| ASA class | 0.020 | ||

| I/II | 87 (63.0) | 156 (75.5) | |

| III/IV | 44 (31.9) | 44 (21.2) | |

| Unknown | 7 (5.1) | 8 (3.8) | |

| Primary surgery | |||

| Indication primary surgery | |||

| Cholecystolithiasis | 66 (47.8) | 115 (55.3) | 0.174 |

| Cholecystitis | 58 (42.0) | 51 (24.5) | < 0.001 |

| Gallbladder wall abnormality1 | 12 (8.7) | 31 (14.9) | 0.087 |

| Other | 2 (1.4) | 11 (5.3) | 0.066 |

| Primary surgery type | |||

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 70 (50.7) | 139 (66.8) | 0.003 |

| Open cholecystectomy | 15 (10.9) | 21 (10.1) | 0.818 |

| Converted cholecystectomy | 39 (28.3) | 35 (16.8) | 0.011 |

| Other | 14 (10.1) | 13 (6.3) | 0.186 |

| Perioperative suspicion of GBC | 0.757 | ||

| Reported | 17 (12.3) | 28 (13.5) | |

| Unreported | 121 (87.7) | 180 (86.5) | |

| Pathology | |||

| T stage | 0.005 | ||

| Is/1a | 9 (6.5) | 31 (14.9) | |

| 1b | 17 (12.3) | 12 (5.8) | |

| 2 | 49 (35.5) | 97 (46.6) | |

| 3/4 | 34 (24.6) | 39 (18.8) | |

| x | 29 (21.0) | 29 (13.9) | |

| Morphology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 115 (83.3) | 177 (85.1) | 0.658 |

| Other | 8 (5.8) | 19 (9.1) | 0.257 |

| Unknown | 15 (10.9) | 11 (5.3) | 0.054 |

| Resection margin | < 0.001 | ||

| R0 | 51 (37.0) | 117 (56.3) | |

| R1 | 52 (37.7) | 51 (24.5) | |

| R2 | 14 (10.1) | 12 (5.8) | |

| Unknown | 21 (15.2) | 28 (13.5) | |

| Regional lymph node metastasis | 0.027 | ||

| N0 | 5 (3.6) | 26 (12.5) | |

| N1 | 14 (10.1) | 20 (9.6) | |

| Nx | 119 (86.2) | 162 (77.9) |

The indication for primary surgery was cholecystitis in 58 patients (40.1%) with bile spillage vs 51 patients (24.5%) without bile spillage (P < 0.001). In patients with bile spillage, conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy occurred more frequently (28.3% vs 16.8%, P = 0.011). Patients with bile spillage had pT3/T4 disease more frequently [n = 34 (24.6%) vs n = 39 (18.8%), P < 0.001]. Non-radical resection margins of primary surgery were more frequently reported in patients with bile spillage: 66 patients with bile spillage (47.8%) vs 63 patients without bile spillage (30.3%) (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Positive or negative lymph nodes during primary surgery were described in pathology reports of 65 patients (19.0%). Positive lymph nodes were described in 34 patients. The amount of resected lymph nodes was one or two in all but 1 patient who underwent primary surgery at a tertiary center and had nine lymph nodes harvested of which one positive.

Details about additional surgery were known of 327 patients. Patients who had bile spillage during their initial surgery were found to have a lower likelihood of undergoing subsequent curative intent surgery. Specifically, only 26.2% of patients with bile spillage underwent additional surgery compared with 38.6% of patients without bile spillage (P = 0.020). Staging laparoscopy was performed in 6/34 patients (17.6%) with bile spillage who underwent additional surgery with curative intent vs only 5/76 patients (6.6%) without bile spillage (P = 0.042). Subsequently, during re-exploration a higher proportion of patients with bile spillage (n = 14, 41.2%) had irresectable disease compared with 17 patients without bile spillage (22.4%) (P = 0.043). Among those who underwent re-resection, patients with bile spillage had a higher rate of non-radical resection margins, with 4 patients (25.0%) exhibiting R1 margins compared with 2 patients (4.1%) without bile spillage (P = 0.012) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Bile spillage (n = 138) | No bile spillage (n = 208) | P value |

| Additional imaging performed (n = 324) | 77 (60.6) | 137 (69.5) | 0.098 |

| Patient referred to hepatopancreatobiliary center | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 46 (33.3) | 103 (49.5) | |

| No | 75 (54.3) | 78 (37.5) | |

| Primary center was hepatopancreatobiliary center | 15 (10.9) | 25 (12.0) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.45) | 2 (1.0) | |

| Additional surgery with curative intent (n = 327) | 34 (26.2) | 76 (38.6) | 0.020 |

| Staging laparoscopy performed before additional surgery (n = 110) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (6.6) | 0.042 |

| Irresectable during staging laparoscopy or re-resection (n = 110) | 14 (41.2) | 17 (22.4) | 0.043 |

| R1 margin at re-resection (n = 65) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (4.1) | 0.012 |

| Lymph node involvement at re-resection (n = 77) | 8 (38.1) | 19 (33.9) | 0.733 |

| (Neo) adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 317) | 9 (7.0) | 15 (7.9) | 0.765 |

| (Neo) adjuvant radiotherapy (n = 315) | 5 (4.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0.188 |

| Recurrence | |||

| In any organ (n = 218) | 55 (65.5) | 57 (42.5) | < 0.001 |

| Local/Liver | 40 (47.6) | 40 (29.9) | 0.008 |

| Peritoneal | 16 (19.0) | 16 (11.9) | 0.149 |

| Lymph nodes | 9 (10.7) | 11 (8.2) | 0.533 |

| Port site | 5 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.004 |

| Other | 16 (19.0) | 17 (12.7) | 0.202 |

| Not otherwise specified | 4 (4.8) | 7 (5.2) | 0.879 |

| Unknown | 21 (20.0) | 33 (19.8) | 0.962 |

| Time to recurrence (months)1 | 9.9 (6.9–12.8) | 14.7 (11.3–18.0) | 0.004 |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy (before re-resection) was not administered in any of the included patients. Adjuvant chemotherapy was described in 9 patients with bile spillage, of which 4 patients received as palliative vs 15 patients without bile spillage, of which 6 patients received as palliative. Radiotherapy was reported in 5 patients with bile spillage, all as palliative vs 3 patients without bile spillage, of which 1 patients received as adjuvant and 2 patients received as palliative (Table 2).

Data on recurrence was missing in 56 patients. Of the 218 patients in whom data on recurrence was available, 106 did not have signs of disseminated disease on imaging or during (re-)resection. Recurrence occurred in 55 patients with bile spillage (65.5%) and 57 patients without bile spillage (42.5%) (P < 0.001). Median time to recurrence was 10 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 7-13 months] in patients with bile spillage vs 15 months (95%CI: 11-18 months) in patients without bile spillage (P = 0.004). In patients where additional imaging after primary surgery was performed, recurrence or non-resectable disease was found in 17 patients with bile spillage (17.2%) vs 14 patients without bile spillage (11.4%) (P = 0.216).

Local or hepatic recurrence was observed in 40 patients with bile spillage (47.6%) and 40 patients without bile spillage (29.9%) (P = 0.008). Peritoneal recurrence occurred in 16 cases (19.0%) with bile spillage vs 16 cases (11.9%) without bile spillage (P = 0.149). Recurrence in lymph nodes was noted in 9 patients (10.7%) with bile spillage compared with 11 patients (8.2%) without bile spillage (P = 0.533). Additionally, port site metastases were reported in 5 patients with bile spillage (6.0%) but were absent in patients without bile spillage (P = 0.004) (Table 2).

Recurrence was not described in any of the 8 patients with intentional iatrogenic bile spillage. Local or hepatic recurrence was described in 26/73 patients (35.6%) with accidental iatrogenic bile spillage, 4/19 patients (21.1%) with needle aspiration, and 2/9 patients (22.2%) with inflammatory bile spillage. Peritoneal recurrence was described in 10 patients (13.7%) with accidental iatrogenic bile spillage, 2 patients (10.5%) with needle aspiration, and 1 patient (11.1%) with inflammatory bile spillage.

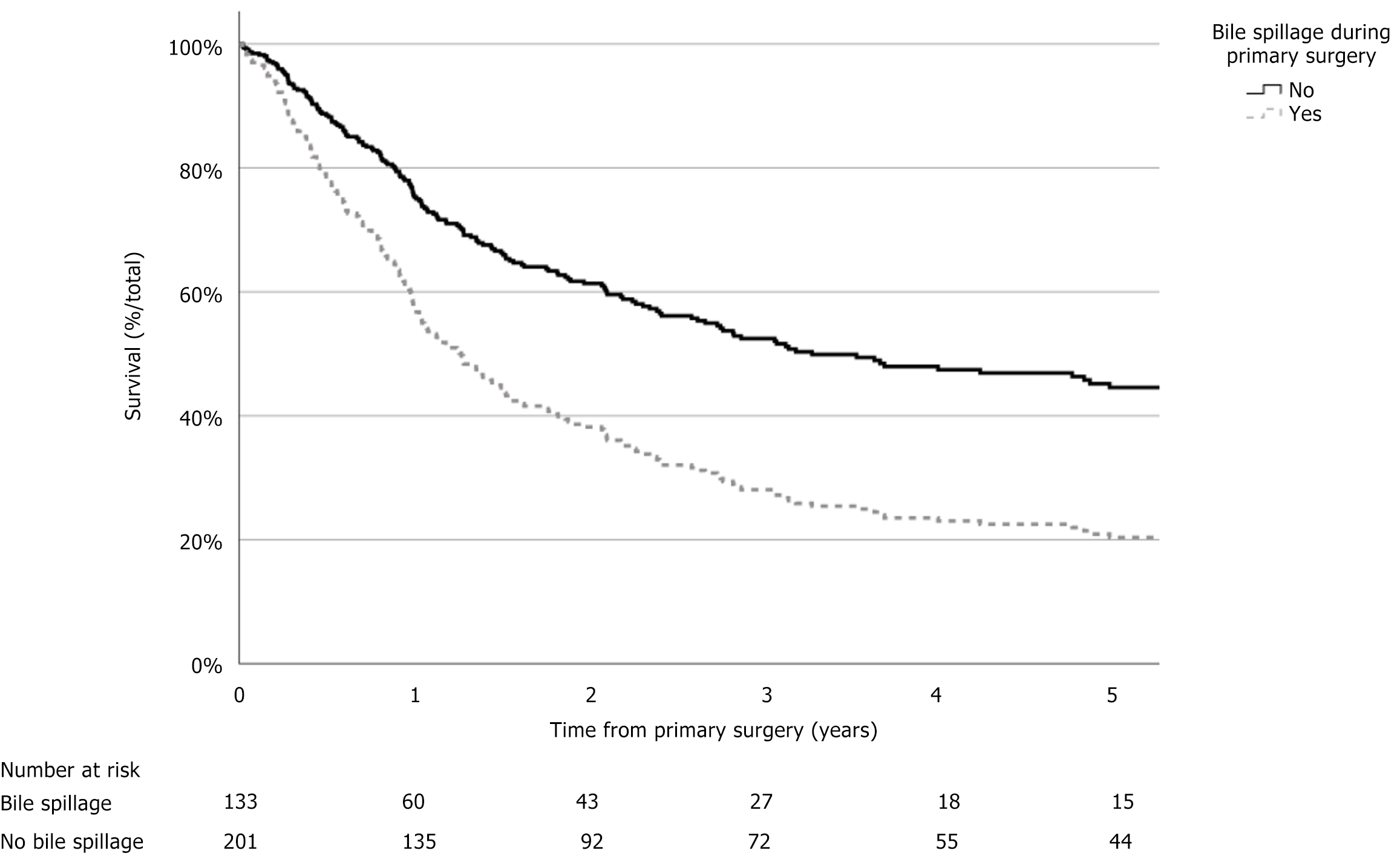

Follow-up data was available in 334 patients. The median OS was 26 months (95%CI: 19-33 months). The 3-year survival was 37.6% (n = 99), and the 5-year survival was 25.3% (n = 60). Of the 133 patients with bile spillage, the median OS was 12 months (95%CI: 7-18 months) vs 34 months (95%CI: 14-55 months) in 201 patients without bile spillage [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.97, 95%CI: 1.48–2.63, P < 0.001]. Age at diagnosis above 65 years, ASA class of III or IV, cholecystitis as indication for surgery, converted primary surgery, pT stage, positive resection margin, regional lymph node, and distant metastasis were also associated with worse survival (P < 0.001) (Figure 2, Table 3).

| Characteristic1 (n) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | P value2 | Adjusted HR (95%CI) (n = 261) | P value3 |

| Age at diagnosis ≥ 65 years (334)4 | 2.01 (1.46-2.77) | < 0.001 | 1.80 (1.22-2.66) | 0.003 |

| ASA III/IV (319)4 | 1.81 (1.32-2.47) | < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.09-2.25) | 0.016 |

| Cholecystitis indication for surgery (334)4 | 1.89 (1.40-2.54) | < 0.001 | 2.13 (1.50-3.04) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery type laparoscopic (334)5 | 0.43 (0.32-0.58) | < 0.001 | ||

| Surgery type converted (334)5 | 2.44 (1.75-3.41) | < 0.001 | ||

| Bile spillage (334)4 | 1.97 (1.48-2.63) | < 0.001 | 1.21 (0.84-1.74) | 0.313 |

| pT stage primary surgery (278)4 | 1.77 (1.45-2.15) | < 0.001 | 1.48 (1.17-1.89) | 0.001 |

| Positive resection margin at primary surgery (287)4 | 2.82 (2.05-3.89) | < 0.001 | 2.42 (1.65-3.55) | < 0.001 |

| pN1 at primary surgery (64) | 3.46 (1.59-7.50) | < 0.001 |

In multivariable analysis, bile spillage was not an independent prognostic factor for impaired OS (HR = 1.21, 95%CI: 0.84-1.74, P = 0.313). Age at diagnosis above 65 years (HR = 1.80, 95%CI: 1.22-.66), ASA class of III or IV (HR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.09-2.25), cholecystitis as indication for surgery (HR = 2.13, 95%CI: 1.50-3.04), pT stage (HR = 1.48, 95%CI: 1.17-1.89), and positive resection margin (HR = 2.42, 95%CI: 1.65-3.55) were all independent prognostic factors associated with worse survival (Table 3).

In 45 included patients (13%), the possibility of GBC was mentioned in the surgery report. This suspicion was mentioned in 17 patients (12%) with bile spillage and 28 patients without bile spillage (14%) (P = 0.757). Exclusion of patients with perioperative suspicion of GBC (n = 45) did not significantly affect outcomes of survival analysis (Table 4).

| Characteristic1 (n) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | P value2 | Adjusted HR (95%CI) (n = 218) | P value3 |

| Age at diagnosis ≥ 65 years (291)4 | 2.19 (1.55-3.10) | < 0.001 | 2.04 (1.35-3.11) | < 0.001 |

| ASA III/IV (279)4 | 1.98 (1.42-2.76) | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.11-2.41) | 0.012 |

| Cholecystitis indication for surgery (291)4 | 1.91 (1.39-2.63) | < 0.001 | 1.98 (1.36-2.88) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery type laparoscopic (291)5 | 0.42 (0.31-0.58) | < 0.001 | ||

| Surgery type converted (291)5 | 2.33 (1.61-3.37) | < 0.001 | ||

| Bile spillage (291)4 | 2.04 (1.50-2.79) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (0.74-1.62) | 0.646 |

| pT stage primary surgery (245)4 | 1.77 (1.44-2.19) | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.17-1.96) | 0.001 |

| Positive resection margin at primary surgery (256)4 | 2.85 (2.03-4.01) | < 0.001 | 2.44 (1.64-3.63) | < 0.001 |

| pN1 at primary surgery (53) | 3.01 (1.31-6.92) | 0.010 |

Cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed procedures in general surgery. Bile spillage occurs in approximately 25% of patients and is a reported risk factor for peritoneal disease and poor outcomes in patients with iGBC[13,19]. In this retrospective, multi-institutional cohort study, bile spillage was associated with a higher risk of non-resectable disease during re-exploration, early recurrence, and poor survival. However, bile spillage was not an independent predictor of survival. Rather, it appeared that bile spillage may more frequently occur in patients with higher T stage or positive resection margin during initial cholecystectomy, factors which are known to negatively affect survival[20,21]. Results from this study highlighted the general practice of managing patients with iGBC undergoing surgery initially intended for a presumed benign condition. Notably, one-fifth of the patients undergoing surgery for cholecystitis were diagnosed with a stage T3/T4 tumor.

It is commonly hypothesized that bile spillage leads to tumor seeding in the intraperitoneal space, causing disseminated disease. Tumor seeding leading to peritoneal disease and early recurrence has been described in colorectal, urological, and gynecological cancers among others[22-24]. Bile samples of patients with GBC contain viable tumor cells, which may contaminate the peritoneum when spilled[25]. Additionally, the stress of surgery and inflammation associated with bile spillage may promote distant metastases due to transport of tumor cells by cytokines, a mechanism known as oncotaxis[26].

Multiple studies have reported increased rates of peritoneal reoccurrence in patients with bile spillage[13,27]. Interestingly, in our study bile spillage was linked to localized rather than peritoneal reoccurrence. It is possible that the size of our cohort was insufficient to discern notable disparities in peritoneal recurrence rates. Furthermore, it is possible that bile spillage predominantly remained confined to the liver and gallbladder bed, resulting in localized rather than peritoneal seeding. To our knowledge no study has shown bile spillage to be an independent factor for reduced OS[12,13,28]. Rather, bile spillage appears to occur more frequently in patients with other poor prognostic factors such as higher T stage and non-radical resection margin. This is substantiated by the loss of effect of bile spillage on survival in multivariable analysis as well as the fact that patients with bile spillage undergo additional surgery with curative intent significantly less often due to other poor prognostic factors such as age and ASA class. Even though bile spillage may not independently impair survival, it is clearly associated with early recurrence[29].

Bile spillage occurred more frequently in patients with a higher T stage. This correlation may be caused by the fact that cholecystectomy is more technically challenging in patients with advanced tumors due to increased difficulty in identifying the correct dissection plane between the gallbladder and surrounding tissue. In our cohort 47% of bile spillage was caused by intentional surgical intervention (i.e. subtotal cholecystectomy) or accidental perforation. When perioperative suspicion of GBC arises, it is advisable to abort the attempted resection and refer a patient to a specialized hepatopancreatobiliary center. Previous studies showed that this practice was safe, and delayed resection does not result in worse survival[6]. In experienced hands redundant cases of bile spillage may be prevented, and subsequently the odds of recurrence could be decreased.

During re-resection, irresectable disease was found in 41% of patients with bile spillage. It is noteworthy that staging laparoscopy prior to re-resection was only carried out in 6 (17.6%) patients with bile spillage eligible for re-resection. The yield of staging laparoscopy in patients with iGBC ranged from 23 to 62% and appeared to be higher in patients with poor prognostic factors[5]. It is recommended to perform a staging laparoscopy before proceeding to re-resection in order to prevent futile laparotomy and associated morbidity.

Interestingly, patients with bile spillage were less likely to be referred to a tertiary hepatopancreatobiliary center (33% vs 50%) and undergo attempted re-resection (26% vs 39%). This difference cannot be explained by differences in T stage alone as according to current guidelines 60% of patients with bile spillage had an indication for additional surgery as opposed to 65% of patients without bile spillage. Possibly, surgeons feel that referral and re-resection are pointless in cases of bile spillage. Another explanation comes from the more common occurrence of bile spillage in patients who are older or have a higher ASA class and are therefore less likely to be referred. The present series showed that patients with bile spillage have reasonable odds of survival, and it is advised that re-resection should still be considered in those patients. Increased awareness amongst community surgeons on the outcomes of patients with bile spillage may contribute to improved referral rates and subsequently better survival of patients with GBC. Undertreatment due to a false dogmatic reflex to consider additional resections/treatment in these patients as futile may have negatively influenced the outcomes of patients with bile spillage. In fact, spillage only accounted for an (insignificant) increase of 11.9% to 19.0% in peritoneal recurrence (P = 0.149).

To our knowledge this study reporting on survival outcomes as a function of bile spillage in gallbladder cancer is the largest cohort available as of date. Moreover, the multi-institutional design geographically spanned most of the country and included data from both secondary and tertiary care centers, whereas most studies on GBC only include the latter. The high quality of the NCR data provided an accurate reflection of contemporary clinical practice as selection and referral bias were minimized. Finally, due to the level of detail of the available data we were able to provide an estimate of the correlation of the type of bile spillage and risk of recurrence.

The primary limitation of this study was the retrospective design. Consequently, there was a significant degree of missing and heterogeneous data. There is a possibility of negligent documentation in surgical reports where bile spillage was not described although it did occur. Additionally, re-resection was frequently not carried out. This may have resulted in understaging of GBC, significantly impacting our findings. Finally, although our cohort was the largest currently available, its size may still be too limited to accurately detect clinically relevant findings. We believe that this is an inherent consequence when conducting research in the field of rare cancers such as GBC. However, it is desirable to confirm our findings through international collaboration with larger cohorts.

While indicative of higher T and N stages and early recurrence and correlated with adverse prognostic factors, bile spillage does not independently impair survival and only marginally increases the risk of peritoneal recurrence. Bile spillage alone should not be regarded as a contraindication for additional treatment or re-resection.

| 1. | Valle JW, Kelley RK, Nervi B, Oh DY, Zhu AX. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 2021;397:428-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 145.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Wernberg JA, Lucarelli DD. Gallbladder cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94:343-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ethun CG, Le N, Lopez-Aguiar AG, Pawlik TM, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees K, Isom CA, Fields RC, Krasnick BA, Weber SM, Salem A, Martin RCG, Scoggins CR, Shen P, Mogal HD, Schmidt C, Beal E, Hatzaras I, Shenoy R, Russell MC, Maithel SK. Pathologic and Prognostic Implications of Incidental versus Nonincidental Gallbladder Cancer: A 10-Institution Study from the United States Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. Am Surg. 2017;83:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | de Savornin Lohman EAJ, van der Geest LG, de Bitter TJJ, Nagtegaal ID, van Laarhoven CJHM, van den Boezem P, van der Post CS, de Reuver PR. Re-resection in Incidental Gallbladder Cancer: Survival and the Incidence of Residual Disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:1132-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Dooren M, de Savornin Lohman EAJ, Brekelmans E, Vissers PAJ, Erdmann JI, Braat AE, Hagendoorn J, Daams F, van Dam RM, de Boer MT, van den Boezem PB, Koerkamp BG, de Reuver PR. The diagnostic value of staging laparoscopy in gallbladder cancer: a nationwide cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ethun CG, Postlewait LM, Le N, Pawlik TM, Buettner S, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees K, Isom CA, Fields RC, Jin LX, Weber SM, Salem A, Martin RC, Scoggins C, Shen P, Mogal HD, Schmidt C, Beal E, Hatzaras I, Shenoy R, Kooby DA, Maithel SK. Association of Optimal Time Interval to Re-resection for Incidental Gallbladder Cancer With Overall Survival: A Multi-Institution Analysis From the US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zaidi MY, Abou-Alfa GK, Ethun CG, Shrikhande SV, Goel M, Nervi B, Primrose J, Valle JW, Maithel SK. Evaluation and management of incidental gallbladder cancer. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Z'graggen K, Birrer S, Maurer CA, Wehrli H, Klaiber C, Baer HU. Incidence of port site recurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preoperatively unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124:831-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Paolucci V, Schaeff B, Schneider M, Gutt C. Tumor seeding following laparoscopy: international survey. World J Surg. 1999;23:989-95; discussion 996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paolucci V. Port site recurrences after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:535-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nishio H, Nagino M, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Nimura Y. Aggressive surgery for stage IV gallbladder carcinoma; what are the contraindications? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:351-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sutton TL, Walker BS, Radu S, Dewey EN, Enestvedt CK, Maynard E, Orloff SL, Nabavizadeh N, Sheppard BC, Lopez CD, Billingsley KG, Mayo SC. Degree of biliary tract violation during treatment of gallbladder adenocarcinoma is independently associated with development of peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124:581-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Horkoff MJ, Ahmed Z, Xu Y, Sutherland FR, Dixon E, Ball CG, Bathe OF. Adverse Outcomes After Bile Spillage in Incidental Gallbladder Cancers: A Population-based Study. Ann Surg. 2021;273:139-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5754] [Cited by in RCA: 11721] [Article Influence: 651.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Casparie M, Tiebosch AT, Burger G, Blauwgeers H, van de Pol A, van Krieken JH, Meijer GA. Pathology databanking and biobanking in The Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol. 2007;29:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hendrix JM, Garmon EH. American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. 2025 Feb 11. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Castor, EDC. Castor Electronic Data Capture. Available from: https://castoredc.com. |

| 18. | AJCC Member Organizations. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. London, United Kingdom: Springer, 2017. |

| 19. | Decker MR, Dodgion CM, Kwok AC, Hu YY, Havlena JA, Jiang W, Lipsitz SR, Kent KC, Greenberg CC. Specialization and the current practices of general surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kihara Y, Yokomizo H, Murotani K. Impact of acute cholecystitis comorbidity on prognosis after surgery for gallbladder cancer: a propensity score analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, D'Angelica M, Dematteo RP, Blumgart LH, O'Reilly EM. Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:485-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Zirngibl H, Husemann B, Hermanek P. Intraoperative spillage of tumor cells in surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:610-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shamberger RC, Guthrie KA, Ritchey ML, Haase GM, Takashima J, Beckwith JB, D'Angio GJ, Green DM, Breslow NE. Surgery-related factors and local recurrence of Wilms tumor in National Wilms Tumor Study 4. Ann Surg. 1999;229:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim HS, Ahn JH, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Lee HP, Kim YB. Impact of intraoperative rupture of the ovarian capsule on prognosis in patients with early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:279-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tanaka N, Nobori M, Suzuki Y. Does bile spillage during an operation present a risk for peritoneal metastasis in bile duct carcinoma? Surg Today. 1997;27:1010-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hirai T, Matsumoto H, Yamashita K, Urakami A, Iki K, Yamamura M, Tsunoda T. Surgical oncotaxis--excessive surgical stress and postoperative complications contribute to enhancing tumor metastasis, resulting in a poor prognosis for cancer patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;11:4-6. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Sandstrom P, Bjornsson B. Bile spillage should be avoided in elective cholecystectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2019;8:640-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Blakely AM, Wong P, Chu P, Warner SG, Raoof M, Singh G, Fong Y, Melstrom LG. Intraoperative bile spillage is associated with worse survival in gallbladder adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:603-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hunter LA, Soares HP. Quality of Life and Symptom Management in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:5074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/