Published online Jul 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106365

Revised: March 30, 2025

Accepted: June 6, 2025

Published online: July 27, 2025

Processing time: 149 Days and 22.2 Hours

The presence of a large paraesophageal hernia is a source of concern in foregut surgery. Thus, scholars have focused on ascertaining the optimal surgical approach, methods for reinforcing the esophageal hiatus, and strategies for preventing hernia recurrence and gastroesophageal reflux.

To investigate the outcomes of surgery for giant paraesophageal hernias without sac removal.

Sixty-six consecutive patients who underwent surgery for a giant paraesophageal hernia between May 2010 and December 2024 were included in this retrospective study. The pre- and postoperative examinations included upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, X-ray with barium contrast swallow, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and abdomen, 24-hour potential hydrogen esophageal monitoring, and esophagomanometry. The study group included 36 patients who underwent surgery without sac removal, and the control group included 30 patients who underwent surgery with sac removal.

Fifty-two patients (28 in the study group and 24 in the control group) underwent laparoscopic procedures, 10 (6 in the study group and 4 in the control group) underwent open procedures, and 4 (2 in each group) underwent conversion procedures. The operative time and postoperative length of stay were significantly longer in the control group than in the study group. In 12 patients in the study group, X-ray examination on postoperative days 3-5 revealed air-fluid levels at the site of the remaining hernia sac; all air-fluid levels disappeared without intervention 2 months later. Postoperative day 60 CT and X-ray examinations revealed no pathological changes related to the hernia sac in the mediastinum.

Removal of the hernia sac during surgery for giant paraesophageal hernias is not mandatory. Further large-scale multicentric randomized trials are needed for a more detailed investigation in this field.

Core Tip: This article highlights several technical aspects of surgery for “giant” paraesophageal hiatal hernias. The step involving the evacuation of the hernia contents and mobilization of the sac was emphasized in this study. The findings of this investigation underscore the importance of technical aspects of surgery for giant paraesophageal hiatal hernias, reinforcing the hiatus and assessing the need for antireflux interventions.

- Citation: Hakobyan VM, Petrosyan AA, Yeghiazaryan HH, Aleksanyan AY, Safaryan HH, Shmavonyan HH, Papazyan KT, Ayvazyan KH, Davtyan LG, Khachatryan AA, Sargsyan GS, Stepanyan SA. Removal of the sac during surgery for the repair of “giant” paraesophageal hernias. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(7): 106365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i7/106365.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106365

The prevalence of hiatal hernias (HHs) is estimated to range between 13% and 59%; however, this estimated prevalence may be under- or overestimated, as there are no large-scale population-based studies on HHs[1-3].

To date, most reported cases of HHs are sliding hernias (type I HHs according to the Landrenau classification), which are prevalent and commonly treated by gastroenterologists[4]. All patients with paraesophageal herniation (types II, III and IV HH) have indications for surgery[2,4]. Untreated paraesophageal HHs (PHHs) may cause potentially fatal complications, such as strangulation, incarceration and perforation[2,4-6]. PHHs represent 5%-10% of all HHs and typically occur in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities[7-9].

Giant paraesophageal hernias remain a subject of debate. Given that there is no standard definition of a giant PHH, some researchers have defined giant PHHs as hernias with displacement of 30%-50% of the stomach into the intrathoracic region and classified them as type III or IV hernias[10-12].

Giant PHHs complicate foregut surgery and are associated with high risks of morbidity and recurrence. Laparoscopic surgery is currently the standard technique for such cases[2,13], as it is associated with low risks of morbidity and mortality[14].

Several techniques have been proposed for paraesophageal hernia repair[2,4,7,8]. Some details of these procedures are disputable, one of which is hernia sac dissection, which prolongs the operation and can cause intraoperative complications such as bleeding and injury to mediastinal structures.

Several authors have recommended complete dissection of the hernia sac, followed by evacuation of its contents and complete removal from the mediastinum[14], whereas others have suggested meticulous dissection and excision of the hernia sac[15-17].

In all the articles cited, the authors have provided little information about the intra- and postoperative complications of hernia sac removal from the mediastinum and no data on elective surgery for different-sized hernias.

A total of 207 consecutive patients with PHHs underwent surgery at the Republican Medical Center “Armenia” (Yerevan, Armenia) between May 2010 and August 2018 and at the Mikaelyan Institute of Surgery (Yerevan, Armenia) between September 2018 and December 2024. There were 36 patients with giant PHHs in the study group and 30 in the control group.

The preoperative evaluations included upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, X-ray with barium contrast swallow, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen, 24-hour potential of hydrogen (pH) esophageal monitoring (VISION IFU, 24-hour pH-metry, Italy), and esophagomanometry (SolarTM Gastrointestinal High Resolution Manometry, Laborie, France). The postoperative examinations included upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, X-ray with barium contrast swallow and contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest and abdomen.

Patients with a type II, III or IV paraesophageal hernia with more than 1/3 of the stomach pouch located in the chest.

Patients who previously underwent surgery on the diaphragm and/or for an HH. The Visick scale was used to score the clinical effectiveness of the surgery. The patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic or via telephone interviews two and twelve months after surgery.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mikaelyan Institute of Surgery.

The data were collected and entered into a database. Statistical analysis was performed with MS Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp., United States). Analysis of variance (F test) and the χ2 test were used to calculate the P value. A P value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance. During the calculation of the P value, the rows and columns having only results of 0 were excluded. Data that are not statistically significant are not denoted.

All the operations were elective and performed under general anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotics were administered before surgery.

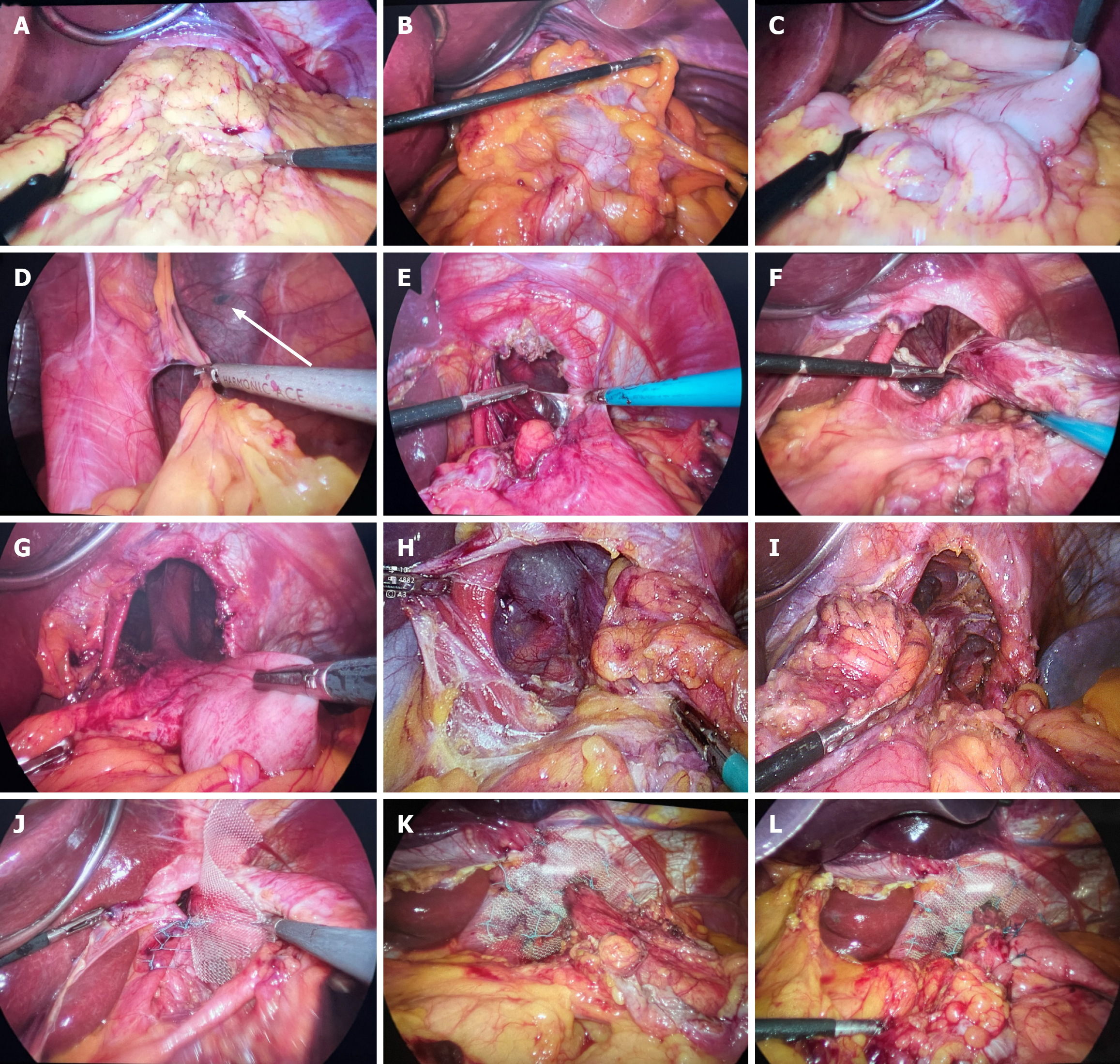

The open procedures were performed via upper median laparotomy in the 200-300 reverse Trendelenburg position. For the laparoscopic procedures, the patients were placed in a combined 200-300 reverse Trendelenburg and French position. Capnoperitoneum was created with a Veress needle (51 patients) or with an open trocar (5 patients), leading to a constant intra-abdominal pressure of 14 mmHg. Four trocars were placed in the abdominal wall at various sites: A 10 mm trocar was placed in the left mesogastrium for the 300 video scope, a 10 mm trocar was placed above the umbilicus for the Babcock grasper, and 5 mm trocars were placed in the right and left subcostal areas for the working instruments. A Nathanson liver retractor (5 mm) was inserted into the upper epigastrium. LigaSure (ForceTriad Energy Platform, Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States) or a Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endosurgery, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, United States) was used for tissue mobilization. The hernia content was carefully mobilized and reduced into the abdominal cavity (Figure 1A-D).

In the study group, the neck of the hernia sac was mobilized and cut at the level of the diaphragmatic crura (Figure 1E-G), and then the esophagogastric junction and the lower part of the esophagus were mobilized. In all patients, the hernia sac was left in the mediastinum. In the control group, the whole hernia sac was mobilized and then removed (Figure 1H and I).

The vagus nerves were identified and left attached to the esophagus. The short gastric vessels and the gastro-diaphragmatic ligament were divided to mobilize the gastric fundus.

After mobilization, the diaphragmatic crura was exposed following the creation of a wide posterior window behind the esophagus. After mobilization of the esophagogastric junction, 3 cm-4 cm of the esophagus was pulled down into the abdomen. Crurorrhaphy was routinely performed with nonabsorbable sutures (2-0 Ethibond; Ethicon, Spreitenbach, Switzerland; 3-0 PremiCron, B. Braun, Barcelona, Spain) after the placement of a 36Fr orogastric tube (Figure 1J). A 10 cm × 10 cm polypropylene mesh (Prolene; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ, United States; Optilen mesh, B. Braun, Germany) was fixed around the esophagus with nonabsorbable stitches (Figure 1K). Reinforcement of the hiatus was combined with antireflux 3600 Nissen fundoplication (Figure 1L). Two nonabsorbable sutures were used to create a 2 cm-3 cm long wrap, which was fixed to the anterior wall of the esophagogastric junction and esophagus. The left subdiaphragmatic area was drained via a Penrose tube inserted in the left subcostal region.

The common complaints in the preoperative period were chest pain, heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. The mean period from symptom onset to surgery was 46 months (range 10-120 months) in both groups. The patients’ demographic and preoperative characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Hiatal hernia repair without removal of the hernia sac (n = 36, 54.5%) | Hiatal hernia repair with removal of the hernia sac (n = 30, 45.5%) | P value | |

| Age, years, median (range) | 54.8 (29-81) | 54.6 (28-72) | |

| Sex, female | 23 (63.9) | 21 (70) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range) | 29.6 (24.6-35.1) | 29.7 (24.6-36.8) | |

| ASA | |||

| II | 23 (63.9) | 22 (73.3) | |

| III | 13 (36.1) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Esophagitis | 14 (38.9) | 12 (40) | |

| Grade A | 8 (22.2) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Grade B | 4 (11.1) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Grade C | 1 (2.78) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Grade D | 1 (2.78) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Preoperative PPI use | 24 (66.7) | 21 (70) |

No patient had a history of previous operations for HH or gastroesophageal reflux disease. None of the patients in either group had a short esophagus.

All patients with giant PHHs underwent preoperative CT of the chest and abdomen. Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring revealed acid exposure in the esophagus in 28 patients. Endoscopic evaluation revealed esophagitis in 26 patients (Table 1).

The exact degree of paraesophageal involvement of the hernia was determined intraoperatively. The distribution of PHH types is presented in Table 2. The intrathoracic stomach was revealed intraoperatively in 19 patients.

| Hiatal hernia repair without removal of the hernia sac (n = 36) | Hiatal hernia repair with removal of the hernia sac (n = 30) | P value | |

| Method of operation | |||

| Laparoscopy | 28 (77.8) | 24 (80) | |

| Open | 6 (16.7) | 4 (13.3) | |

| Conversion | 2 (5.5) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Type of PHH | |||

| Type II | 17 (47.2) | 14 (46.7) | |

| Type III | 12 (33.3) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Type IV | 7 (19.5) | 6 (20) | |

| Intrathoracic stomach | 11 (30.6) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Operation time, minute, median (range) | < 0.001 | ||

| Laparoscopy | 114 (100-135) | 144 (125-170) | |

| Open + conversion | 169 (140-185) | 190 (180-200) | |

| Postoperative length of stay, days, median (range) | < 0.001 | ||

| Laparoscopy | 2.4 (2-4) | 2.55 (2-4) | |

| Open + conversion | 5.75 (4-7) | 6.17 (5-7) | |

| Postoperative complications | 9 (25) | 11 (36.7) | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (5.6) | 3 (10) | |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (8.3) | 4 (13.4) | |

| Dysphagia | 4 (11.1) | 3 (10) | |

| Intraabdominal hematoma | 0 (0) | 1 (3.3) | |

| Radiologic recurrence | 7 (19.4) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Asymptomatic | 4 (11.1) | 3 (10) | |

| Symptomatic | 3 (8.3) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Reoperation | 3 (8.3) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Postoperative PPI use | 3 (8.3) | 3 (10) |

Open procedures, such as previous open operations in the upper abdomen (seven patients) and cardiorespiratory failure (three patients), were performed in patients with contraindications for laparoscopy. Seven patients had a history of multiple operations in the epigastric region with median laparotomy. Three patients underwent removal of hydatid cysts of the liver; resection of the transverse colon; two patients underwent removal of hydatid cysts of the spleen; rela

Three patients initially scheduled for laparoscopic surgery required conversion because of adhesions in the upper abdomen that developed after a previous open cholecystectomy, and one patient required conversion due to difficulties in evacuation of the hernia contents.

All the procedures were performed by senior surgeons. No intraoperative complications were detected. There was no in-hospital mortality. The operative time and postoperative length of stay were significantly longer in the control group (Table 2).

Transient dysphagia was noted in seven patients. All cases of dysphagia resolved within four to six weeks. X-ray examination on postoperative days 3-5 revealed retention of barium for 0.5-1.5 minutes in the esophagus in these patients. There were no cases of persistent dysphagia that required endoscopic balloon dilation or reoperation. There were no mesh-related complications. One patient in the control group developed a hematoma in the left subdiaphragmatic region that did not require reoperation, and the contents were evacuated via a drainage tube over a 10-day period. None of the seven cases of pleural effusion required evacuation of the fluid.

During the postoperative period, 11 patients in the study group and 22 patients in the control group experienced transient subcutaneous emphysema in the neck that resolved spontaneously within 24-48 hours.

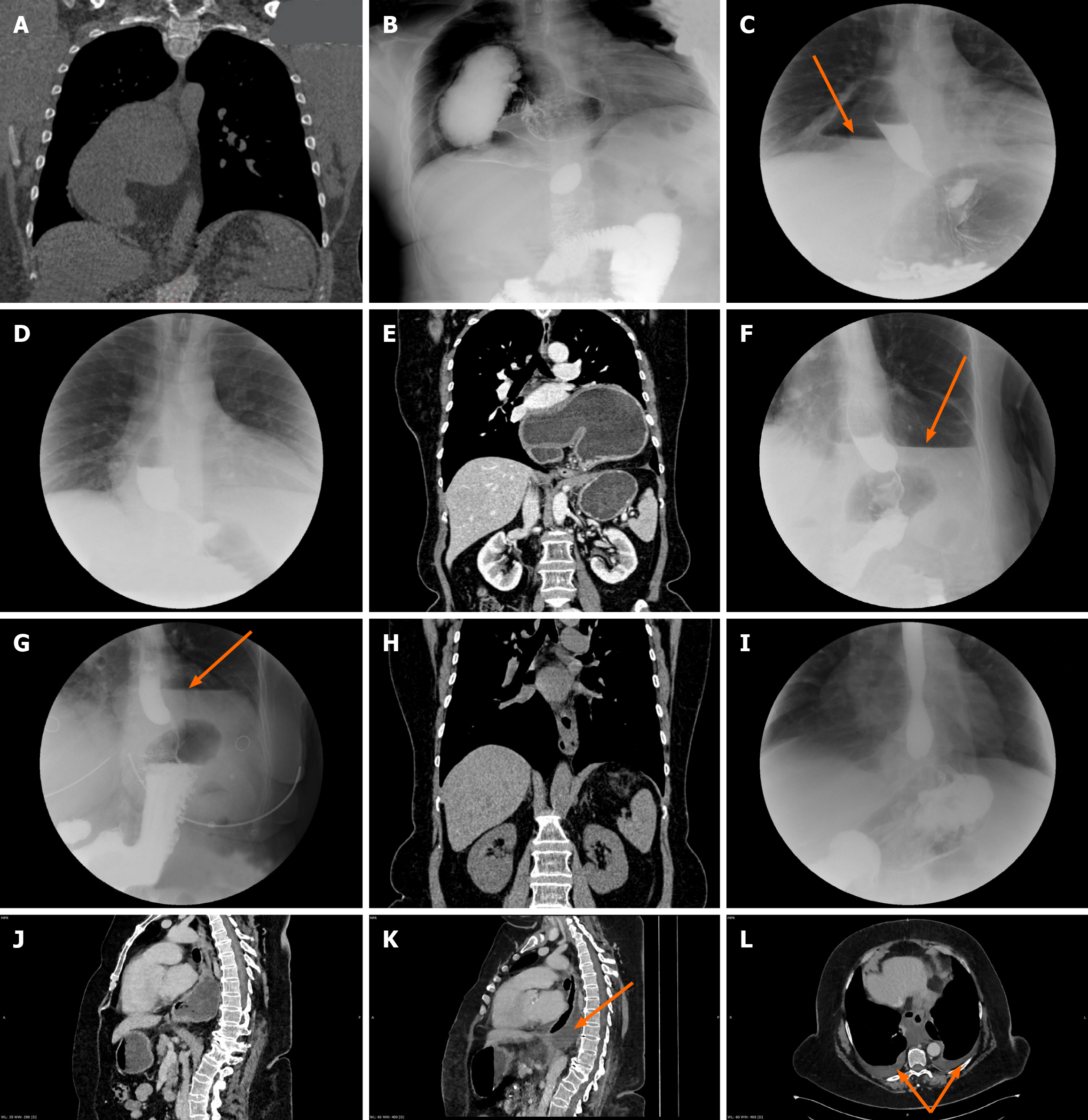

Chest X-ray on postoperative days 3-5 revealed an air-fluid level at the site of the remaining hernia sac in 12 patients in the study group. Two-month postoperative CT and X-ray examinations revealed no pathological changes related to the hernia sac in the mediastinum and that the air-fluid levels had spontaneously disappeared (Figure 2A-H). In the control group, CT and X-ray images revealed effusion in the mediastinum and pleural cavities in four patients (Figure 2I-L).

The patients were asked to return for follow-up examination and barium contrast swallow 2 and 12 months after surgery to rule out radiologic recurrence. A CT scan of the abdomen and chest was performed in 18 patients (12 patients in the study and 6 patients in the control groups) at the 2-month follow-up and in 14 patients (8 patients in the study and 6 patients in the control groups) at the 12-month follow-up because of reports of pain in the retrosternal and epigastric regions. Recurrent hernias were diagnosed via contrast-enhanced CT, barium contrast swallow X-ray and endoscopy. The patients with symptomatic recurrent hernias (two patients who underwent open surgery and three patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery) complained of pain in the chest and the epigastrium, heartburn, dysphagia, and regurgitation (Table 2). All the patients with symptomatic recurrent hernias underwent reoperation (one who underwent laparoscopic surgery and four who underwent open surgery), with satisfactory results. All the recurrent hernias were small in size, with the largest being 3 cm × 5 cm.

The median follow-up duration in the study and control groups was 86 ± 12 months (2-128 months). The results of the patients’ follow-up assessments are presented in Table 3. Thirty-one patients (47%) [19 (65.5%) in the study group and 12 (46.2%) in the control group] underwent comprehensive clinical follow-up assessments. Twenty-four patients (36.4%) [10 (34.5%) in the study group and 14 (53.8%) in the control group] were followed via telephone interview. The remaining 11 (16.6%) patients were unreachable and were therefore considered dropouts. Most patients were satisfied with their decision to undergo surgery; 44 patients (80%) were free of gastrointestinal symptoms or postoperative side effects.

| Hiatal hernia repair without removal of the hernia sac (n = 29) | Hiatal hernia repair with removal of the hernia sac (n = 26) | P value | |

| Visik I | 16 | 12 | |

| Visik II | 7 | 9 | |

| Visik III | 3 | 3 | |

| Visik IV | 3 | 2 |

Giant PHHs are characterized by the presence of more than one-third of the stomach in the chest cavity[9]. In our study, patients with type II, III, or IV paraesophageal hernias with displacement of more than one-third of the stomach into the mediastinum were included (Table 2).

Currently, the preferred method of repair for HHs and giant PHHs is laparoscopy[9]. Since the first minimally invasive operation for PHH was performed by Cuschieri A and colleagues in 1992, laparoscopic repair has become widely accepted as the standard method[18]. The laparoscopic approach to paraesophageal hernia repair is the preferred method, as it is associated with low risks of morbidity and mortality, less postoperative pain, a shorter length of stay and convalescence[19].

Regardless of the approach chosen, there is still a risk of postoperative complications, mainly due to the need for cruroplasty and reinforcement of the diaphragmatic hiatus[20,21]. The optimal technique for repairing large hernias is still unclear, as evidenced by the different results presented in numerous studies[21-25].

However, in most articles, the authors recommend hernia sac removal regardless of the hernia type or sac dimensions.

Some authors have reported that retention of the hernia sac in combination with other causes (a large hiatal orifice, weakness of the crura muscle fibers, inadequate mobilization of the esophagus, injury to the crura during repair and excessive tension on the diaphragm) predisposes patients to hernia recurrence[15]. Other authors have recommended mobilizing and then dissecting the hernia sac from adjacent mediastinal structures[26-28] or mobilizing and reducing the hernia sac intraperitoneally[29]. Some authors have noted the importance of hernia sac dissection, considering that the hernia sac must be mobilized to allow assessment of the intraabdominal length of the esophagus[30,31].

Straatman et al[32] reported a case of a lethal complication after hernia sac excision. The patient died of multiorgan failure after elective PHH repair with gastropexy, causing pleural effusion and inflammation of the excised hernia sac wall[32]. Gastropexy was performed because fundoplication was not technically feasible[32].

We believe that removing the sac of small HHs is justified; however, dissecting the sac of giant hernias, particularly those classified as type III or IV with substantial mediastinal involvement, could be dangerous. The risks of injury to the parietal pleura, vessels and organs in the mediastinum, and hematoma formation must be considered when dealing with such cases. Hernia sac mobilization and removal prolong the operative time. In our study group, the hernia sac was mobilized at the level of the esophageal hiatus. Mobilization of a section of the neck of the sac allowed mobilization of the diaphragmatic crura and the lower part of the esophagus. No further mobilization of the mediastinal part of the sac was needed. In fact, all that is required is to mobilize a sufficient intra-abdominal length of the esophagus above the esophagogastric junction at the level of the neck of the hernia sac. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative complication rates. There were more cases of pleural effusion and pneumonia in our control group. In the same group, there was one case of hematoma formation.

The results of our investigations revealed that retention of the hernia sac does not cause complications in the early postoperative period. The remaining hernia sac was no longer visible at the 2-month postoperative follow-up. Hernia sac mobilization and removal significantly prolonged the operative time in the control group.

The most important steps of HH repair are crurorrhaphy and fundoplication. Successful crurorraphy and solid reinforcement of the esophageal hiatus are the only means of preventing hernia recurrence[21,22,33,34]. The optimal methods for performing crurorrhaphy, reinforcing the esophageal hiatus and preventing hernia recurrence remain the main topics in the surgical literature[34-38].

The main source of concern in this field is the high incidence of recurrence. The recurrence rates of laparoscopically repaired giant PHHs range from 12% to 42%[39].

Failed crus closure is the main cause of recurrence[17,40]. Crus closure has been described as the “Achilles’ heel” of hiatoplasty and antireflux surgery[41,42]. In several studies analyzing laparoscopic suture repair of large hiatal defects, the authors reported failure rates ranging from 11% to 67%, suggesting significant room for improvement[19,36,39,43,44].

Intrathoracic wrap migration and HH recurrence are caused by inadequate closure of the hiatal crura or disruption of the hiatoplasty[20-22]. Therefore, the use of prostheses may reduce the incidence of recurrence[45-48]. Many authors have concluded that more liberal use of mesh during hiatal reinforcement could prove beneficial[2,20,21,46,48]. The recurrence rates were 23.1% after suture repair, 30.8% after absorbable mesh repair, and 12.8% after nonabsorbable mesh repair[49]. Compared with simple suture repair, the use of mesh to reinforce cruroplasty can reduce the recurrence rate in the short term[50]. Müller-Stich et al[22] reported a radiologic recurrence rate of 19% for HHs without mesh reinforcement over a more than 4-year follow-up period. They did not record any signs of PHH recurrence at the 20-month follow-up after the introduction of hiatal mesh reinforcement[22]. The authors recommend that hiatal mesh reinforcement should be routinely performed[22]. The incidence of prosthetic mesh-related complications, even during long follow-up periods, is low[21,44].

Mesh was used in both groups of our study. We believe that the diaphragmatic hiatus should be reinforced with mesh during giant PHH repair surgery. In our opinion, adequate fixation of the mesh is an important step in hernia repair; it prevents injury to or erosion of the surrounding organs.

The rationale for surgery for HHs is to create a functional antireflux barrier[2,5,18,51]. Antireflux procedures are recommended by many surgeons because of the need to compensate for the destruction of the anchoring system of the esophagogastric junction during mobilization as part of treatment for giant PHHs[16,17,52]. In addition, an antireflux procedure is indicated for mixed-type hernias accompanied by gastroesophageal reflux disease[30].

In our study, all patients underwent complete fundoplication. Wrapping the esophagus and fixing the wrap to the esophagus and cardia after the placement of a 36Fr orogastric tube effectively prevents gastroesophageal reflux without causing persistent postoperative dysphagia.

We are well aware of the limitations of our study, which is a nonrandomized retrospective investigation.

The removal of the hernia sac during surgery for “giant” paraesophageal hernias is not mandatory. Mobilization of a section of the neck of the hernia sac at the level of the hiatus benefitted subsequent repair and antireflux procedures. Further large-scale multicentric randomized trials are necessary for a more detailed investigation in this field.

The authors would like to thank Prof. Michel LA and Prof. Kazaryan A for reviewing this paper and providing valuable insights. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr. Mkrtchyan SG and Dr. Ganjalyan L, who performed the radiological assessments, and Dr. Manukyan KD, who performed the endoscopic assessments.

| 1. | Yun JS, Na KJ, Song SY, Kim S, Kim E, Jeong IS, Oh SG. Laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3903-3908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kohn GP, Price RR, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Muensterer OJ, Awad Z, Mittal SK, Richardson WS, Stefanidis D, Fanelli RD; SAGES Guidelines Committee. Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4409-4428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ténaiová J, Tůma L, Hrubant K, Brůha R, Svestka T, Novotný A, Petrtýl J, Jirásek V, Urbánek P, Lukás K. [Incidence of hiatal hernias in the current endoscopic praxis]. Cas Lek Cesk. 2007;146:74-76. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Landreneau RJ, Del Pino M, Santos R. Management of paraesophageal hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:411-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with 1,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1967;53:33-54. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hill LD. Incarcerated paraesophageal hernia. A surgical emergency. Am J Surg. 1973;126:286-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boushey RP, Moloo H, Burpee S, Schlachta CM, Poulin EC, Haggar F, Trottier DC, Mamazza J. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernias: a Canadian experience. Can J Surg. 2008;51:355-360. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dahlberg PS, Deschamps C, Miller DL, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Pairolero PC. Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1125-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Morino M, Giaccone C, Pellegrino L, Rebecchi F. Laparoscopic management of giant hiatal hernia: factors influencing long-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1011-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mitiek MO, Andrade RS. Giant hiatal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:S2168-S2173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Awais O, Luketich JD. Management of giant paraesophageal hernia. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:159-168. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Zehetner J, Demeester SR, Ayazi S, Kilday P, Augustin F, Hagen JA, Lipham JC, Sohn HJ, Demeester TR. Laparoscopic versus open repair of paraesophageal hernia: the second decade. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:813-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Davis SS Jr. Current controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:959-978, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wijnhoven BP, Watson DI. Laparoscopic repair of a giant hiatus hernia--how I do it. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1459-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gouvas N, Tsiaoussis J, Athanasakis E, Zervakis N, Pechlivanides G, Xynos E. Simple suture or prosthesis hiatal closure in laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia: a retrospective cohort study. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:69-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA. Paraesophageal hernias: open, laparoscopic, or thoracic repair? Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2001;11:589-603. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Targarona EM, Novell J, Vela S, Cerdán G, Bendahan G, Torrubia S, Kobus C, Rebasa P, Balague C, Garriga J, Trias M. Mid term analysis of safety and quality of life after the laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Müller-Stich BP, Achtstätter V, Diener MK, Gondan M, Warschkow R, Marra F, Zerz A, Gutt CN, Büchler MW, Linke GR. Repair of Paraesophageal Hiatal Hernias—Is a Fundoplication Needed? A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:602-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG, Brunt ML, Soper NJ, Sheppard BC, Polissar NL, Neradilek MB, Mitsumori LM, Rohrmann CA, Swanstrom LL. Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:461-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Carlson MA, Richards CG, Frantzides CT. Laparoscopic prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal herniorrhaphy. Dig Surg. 1999;16:407-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Memon MA, Siddaiah-Subramanya M, Yunus RM, Memon B, Khan S. Suture Cruroplasty Versus Mesh Hiatal Herniorrhaphy for Large Hiatal Hernias (HHs): An Updated Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29:221-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Müller-Stich BP, Holzinger F, Kapp T, Klaiber C. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair: long-term outcome with the focus on the influence of mesh reinforcement. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:380-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Michael Brunt L, Hunter JG, Demeester TR, Swanstrom LL, Daniel Smith C, Filipi CJ. Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1219-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tam V, Winger DG, Nason KS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mesh vs suture cruroplasty in laparoscopic large hiatal hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2016;211:226-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Asti E, Lovece A, Bonavina L, Milito P, Sironi A, Bonitta G, Siboni S. Laparoscopic management of large hiatus hernia: five-year cohort study and comparison of mesh-augmented versus standard crura repair. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5404-5409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cocco AM, Chai V, Read M, Ward S, Johnson MA, Chong L, Gillespie C, Hii MW. Percentage of intrathoracic stomach predicts operative and post-operative morbidity, persistent reflux and PPI requirement following laparoscopic hiatus hernia repair and fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:1994-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Grimsley E, Capati A, Saad AR, DuCoin C, Velanovich V. Novel "starburst" mesh configuration for paraesophageal and recurrent hiatal hernia repair: comparison with keyhole mesh configuration. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:2239-2246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Addo A, Carmichael D, Chan K, Broda A, Dessify B, Mekel G, Gabrielsen JD, Petrick AT, Parker DM. Laparoscopic revision paraesophageal hernia repair: a 16-year experience at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:624-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Choi AY, Roccato MK, Samarasena JB, Kolb JM, Lee DP, Lee RH, Daly S, Hinojosa MW, Smith BR, Nguyen NT, Chang KJ. Novel Interdisciplinary Approach to GERD: Concomitant Laparoscopic Hiatal Hernia Repair with Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232:309-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | van der Peet DL, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Alonso Poza A, Sietses C, Eijsbouts QA, Cuesta MA. Laparoscopic treatment of large paraesophageal hernias: both excision of the sac and gastropexy are imperative for adequate surgical treatment. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1015-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Allman R, Speicher J, Rogers A, Ledbetter E, Oliver A, Iannettoni M, Anciano C. Fundic gastropexy for high risk of recurrence laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair and esophageal sphincter augmentation (LINX) improves outcomes without altering perioperative course. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:3998-4002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Straatman J, Groen LCB, van der Wielen N, Jansma EP, Daams F, Cuesta MA, van der Peet DL. Treatment of paraesophageal hiatal hernia in octogenarians: a systematic review and retrospective cohort study. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Saino G, Sozzi A, Bonitta G, Micheletto G, Campanelli G, Bona D. Laparoscopic posterior cruroplasty: a patient tailored approach. Hernia. 2022;26:619-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Collet D, Luc G, Chiche L. Management of large para-esophageal hiatal hernias. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Diaz S, Brunt LM, Klingensmith ME, Frisella PM, Soper NJ. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair, a challenging operation: medium-term outcome of 116 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:59-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Galloway KD, Hunter JG, Smith CD. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:745-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pierre AF, Luketich JD, Fernando HC, Christie NA, Buenaventura PO, Litle VR, Schauer PR. Results of laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernias: 200 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1909-15; discussion 1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Trus TL, Bax T, Richardson WS, Branum GD, Mauren SJ, Swanstrom LL, Hunter JG. Complications of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:221-7; discussion 228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hashemi M, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Huprich JE, Quek M, Hagen JA, Crookes PF, Theisen J, DeMeester SR, Sillin LF, Bremner CG. Laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: objective followup reveals high recurrence rate. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:553-60; discussion 560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Bhatti MI, Najfi SM, McMurray A. Metaanalysis of recurrence after laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. JSLS. 2007;11:456-460. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Juhasz A, Sundaram A, Hoshino M, Lee TH, Mittal SK. Outcomes of surgical management of symptomatic large recurrent hiatus hernia. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1501-1508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Granderath FA, Schweiger UM, Kamolz T, Pointner R. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery: a problem of hiatal closure more than a problem of the wrap. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1439-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dallemagne B, Kohnen L, Perretta S, Weerts J, Markiewicz S, Jehaes C. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Long-term follow-up reveals good clinical outcome despite high radiological recurrence rate. Ann Surg. 2011;253:291-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Soricelli E, Basso N, Genco A, Cipriano M. Long-term results of hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2499-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bugridze Z, Parfentiev R, Chetverikov S, Giuashvili S, Kiladze M. Redo Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery in Patients with Hiatal Hernia. Georgian Med News. 2021;23-26. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Frantzides CT, Madan AK, Carlson MA, Stavropoulos GP. A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg. 2002;137:649-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ilyashenko VV, Grubnyk VV, Grubnik VV. Laparoscopic management of large hiatal hernia: mesh method with the use of ProGrip mesh versus standard crural repair. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:3592-3598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sathasivam R, Bussa G, Viswanath Y, Obuobi RB, Gill T, Reddy A, Shanmugam V, Gilliam A, Thambi P. 'Mesh hiatal hernioplasty' versus 'suture cruroplasty' in laparoscopic para-oesophageal hernia surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Watson DI, Thompson SK, Devitt PG, Smith L, Woods SD, Aly A, Gan S, Game PA, Jamieson GG. Laparoscopic repair of very large hiatus hernia with sutures versus absorbable mesh versus nonabsorbable mesh: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2015;261:282-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zhang C, Liu D, Li F, Watson DI, Gao X, Koetje JH, Luo T, Yan C, Du X, Wang Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic mesh versus suture repair of hiatus hernia: objective and subjective outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4913-4922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Fuchs KH, Babic B, Breithaupt W, Dallemagne B, Fingerhut A, Furnee E, Granderath F, Horvath P, Kardos P, Pointner R, Savarino E, Van Herwaarden-Lindeboom M, Zaninotto G; European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). EAES recommendations for the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1753-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Clapp B, Hamdan M, Mandania R, Kim J, Gamez J, Hornock S, Vivar A, Dodoo C, Davis B. Is fundoplication necessary after paraesophageal hernia repair? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:6300-6311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/