Published online Jul 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106026

Revised: March 25, 2025

Accepted: May 23, 2025

Published online: July 27, 2025

Processing time: 155 Days and 3.4 Hours

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is a common psychological problem among patients with cancer, especially elderly patients. For patients with gastric cancer (GC) who have undergone treatments such as surgery, FCR may seriously affect their quality of life and psychological well-being.

To evaluate the FCR in elderly patients with GC undergoing laparoscopic radical surgery in Hefei City and to explore its related influencing factors.

In this study 264 elderly patients with GC who underwent laparoscopic radical surgery in four hospital districts of The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from June 2021 to January 2024 were recruited. Information on basic characteristics, disease characteristics, psychological status, and social support was collected by a questionnaire. In statistical analysis, the t-test and χ2 test were used to analyze the differences between groups. The influencing factors of FCR were analyzed by logistic regression. Based on these influencing factors, a nomogram model was initially constructed to identify patients with GC with high FCR risk.

Elderly patients with GC generally faced higher FCR levels after laparoscopic radical surgery. Among the 264 patients, 168 had clinical symptoms of FCR, and the prevalence rate was 63.64%. Further analysis showed that older age, high mental resilience, and sufficient social support were favorable factors for reducing FCR level, while heavier self-perceived burden, low education level, shorter duration of disease, larger tumor diameter, and more complications were associated with a higher FCR level.

This study demonstrated the significance of psychological interventions and social support strategies in reducing FCR among elderly patients with GC. In the future treatment protocols should be further optimized, and psychological and social support should be enhanced to improve the quality of life for this patient population.

Core Tip: This study investigated the fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) in elderly patients with gastric cancer after laparoscopic radical surgery and identified key influencing factors. Among 264 patients, 63.64% exhibited clinically significant FCR. Protective factors included older age, higher psychological resilience, and social support, while risk factors were higher self-perceived burden, lower education, shorter disease duration, larger tumor diameter, and complications. A nomogram model was constructed to predict FCR risk, highlighting the importance of psychological and social support in improving patient quality of life.

- Citation: Zhu NG, Zhao DD, Cui H, Sun SH. Fear of cancer recurrence and influencing factors in elderly patients with gastric cancer undergoing laparoscopic radical surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(7): 106026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i7/106026.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.106026

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most prevalent and lethal malignant tumors globally, particularly affecting the elderly population[1]. The GLOBOCAN revealed that approximately 970000 new cases of GC were diagnosed globally in 2022, with approximately 660000 associated deaths, ranking fifth in both incidence and mortality[2]. It is notable that the incidence and mortality rate of GC in the Chinese population accounts for more than one-third of the global total, which has significant economic and medical implications[3]. As the population continues to age, the number of elderly patients with GC is rising annually, presenting new challenges for clinical treatment and health management[4].

Laparoscopic radical surgery represents a significant advancement in the treatment of GC, offering a minimally invasive approach with reduced trauma and accelerated recovery compared with traditional surgical methods[5]. Chen et al[6] found that patients with GC who underwent laparoscopic radical resection showed better prognosis compared with those who underwent conventional open gastrectomy. Furthermore, in a retrospective analysis of 310 patients with GC, Romero-Peña et al[7] found that the laparoscopic approach to GC had a lower complication rate as well as mortality. However, due to the inherent uncertainty of cancer recurrence, as well as the unique physiological and psychological characteristics of elderly patients, patients after laparoscopic radical surgery may still face a high fear of cancer recurrence (FCR).

Cancer recurrence can have a profound impact on the quality of life of patients, increase the financial burden on healthcare systems, and result in considerable psychological distress for patients and their families[8]. Elderly patients may experience an elevated level of fear regarding cancer recurrence, attributable to physiological decline, increased comorbidities, and comparatively diminished psychological resilience, all of which significantly influence their recovery and overall quality of life[9].

FCR is characterized by the apprehension and heightened concern experienced by patients with cancer regarding the potential for cancer recurrence or progression[10]. In patients with cancer FCR is recognized as a significant factor influencing their mental health and overall quality of life. Research indicates that FCR is closely associated with heightened levels of anxiety and depression among patients, which may subsequently impact their adherence to treatment protocols[11]. However, at present, there are relatively few studies on the level of FCR in elderly patients with GC, especially in China, a country with a high incidence of GC.

Elderly patients with GC have shown a gradual decline in physiological functions, increased comorbidities, and a relatively weakened psychological tolerance that makes them more prone to psychological fear when facing cancer. Especially after undergoing laparoscopic radical surgery, the FCR and uncertainty about their future life may exacerbate their FCR level. As an important psychological reaction, FCR not only affects the psychological state of patients but also may have a negative impact on the therapeutic effect and prognosis. Therefore, in-depth research on the FCR level in elderly patients with GC and its related influencing factors is of great significance for developing personalized psychological intervention measures and improving the psychological resilience of patients.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the fear level of cancer recurrence and its related influencing factors in elderly patients with GC undergoing laparoscopic radical surgery in Hefei city through a cross-sectional design. Through this study we hoped to gain an in-depth understanding of the psychological state of elderly patients with GC, provide targeted psychological interventions for the clinic, improve the quality of life of patients, and reduce the level of FCR. In addition, the results of this study will also provide a theoretical basis and data support for future intervention research.

As a cross-sectional survey, 264 patients with GC hospitalized in the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from June 2021 to January 2024 were strictly selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All patients in this study met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged 60 or older; (2) Patients who were pathologically diagnosed with GC and underwent laparoscopic radical surgery; (3) Patients who were aware of their diagnosis and condition; and (4) Patients with normal cognitive and literacy skills. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with severe comorbidities or other malignancies; (2) People with mental illness or cognitive impairment; (3) Patients with speech disorders and inability to express themselves normally; and (4) Patients who were unwilling or unable to cooperate with the questionnaire. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University. All patients in this study signed informed consent voluntarily.

In this study, 264 patients were investigated by the general data questionnaire, the fear of progression questionnaire short form (FoP-Q-SF), Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC), social support rating scale (SSRS), and self-perceived burden scale (SPBS). FoP-Q-SF was developed by Mehnert et al[12] and adjusted by Wu et al[13]. FoP-Q-SF consists of 12 items, each rated on a scale of 1-5, with a total score of ≥ 34 considered clinically significant. Its Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.883.

CD-RISC was developed by psychology professors Connor and Davidson[14]. CD-RISC contains 25 entries in 5 dimensions, with each entry scoring 0-4 points. The higher the score of CD-RISC, the higher the level of psychological resilience, with a total score of 0-56 indicating a low level, 57-70 indicating a moderate level, and 71-100 indicating a high level. Its Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.861.

SSRS is divided into three dimensions, a total of 10 items, from the objective support, subjective support and support utilization of three aspects of evaluation[15]. The SSRS scale scores range from 12 to 66, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. Its Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.856.

SPBS was developed by Cousineau et al[16] and localized by Tang[17]. SPBS has three dimensions and ten items, using a Likert 1-5 rating system. The SPBS score is calculated based on the burden level of the crossbeam patients after summation, with a score range of 10-50 points. The higher the score, the heavier the perceived burden. Its Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.945.

Before investigation, the consent and support of the department leaders were sought. The researchers conducted a face-to-face questionnaire survey on the subjects eligible for inclusion. The researchers used a unified interpretation to explain the purpose, meaning, and content of the survey to the patients. Before conducting the questionnaire, the investigators fully explained the specific content of the study to the patients and guided them on how to fill out the questionnaire. All questionnaires were filled out by the subjects. If it was impossible to fill in the questionnaire due to educational level, an investigator asked questions according to the questionnaire content, and some patients gave oral answers. After filling in the questionnaire, the researcher collected and checked the questionnaire on site. In the event of a missing or incorrect filling, the questionnaire was replenished by the patient and collected within the specified timeframe. A total of 280 questionnaires were sent out in this study, and 264 were effectively collected, with an effective recovery rate of 94.89%.

The measurement data were described in the form of mean ± SD, and the difference between groups was analyzed by the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The classification data were described in the form of frequency and percentage, and the χ2 test and Fisher exact probability method were used to analyze the difference between groups. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the correlation between FCR and psychological resilience, social support, and medical coping in patients with GC. Multiple linear regression was used to analyze the influencing factors of FCR in elderly patients with GC. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0. All statistical tests were bilateral, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 264 postoperative patients with GC, the average score of the FoP-Q-SF was 37.62 ± 7.41. There were 168 patients with scores ≥ 34 who were considered to have clinical symptoms of FCR. In this study, the prevalence of FCR was 63.64%. The mean age was 67.16 ± 4.72 in the normal group and 64.87 ± 4.46 in the FCR group, showing significant difference (P < 0.001) (Table 1). The proportion of the normal group receiving high school education or above was 45.83%, significantly higher than the 31.55% in the FCR group (P = 0.021). The level of psychological resilience (65.52 vs 60.85, P < 0.001) and social support (45.16 vs 43.30, P = 0.003) in the normal group was significantly higher than that in the FCR group, while the level of self-perceived burden (28.72 vs 31.11, P = 0.004) was significantly lower than that in the FCR group.

| Variables | Total (n = 264) | Normal group (n = 96) | FCR group (n = 168) | Statistic | P value |

| Age | 65.70 ± 4.68 | 67.16 ± 4.72 | 64.87 ± 4.46 | t = 3.86 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | χ² = 0.43 | 0.512 | |||

| Female | 117 (44.32) | 40 (41.67) | 77 (45.83) | ||

| Male | 147 (55.68) | 56 (58.33) | 91 (54.17) | ||

| Spouse | χ² = 0.45 | 0.500 | |||

| Yes | 223 (84.47) | 83 (86.46) | 140 (83.33) | ||

| No | 41 (15.53) | 13 (13.54) | 28 (16.67) | ||

| Educational level | χ² = 5.36 | 0.021 | |||

| High school and above | 97 (36.74) | 44 (45.83) | 53 (31.55) | ||

| Junior high school and below | 167 (63.26) | 52 (54.17) | 115 (68.45) | ||

| Household income | χ² = 1.68 | 0.194 | |||

| High income | 110 (41.67) | 45 (46.88) | 65 (38.69) | ||

| Low income | 154 (58.33) | 51 (53.12) | 103 (61.31) | ||

| Residence | χ² = 0.54 | 0.461 | |||

| Urban areas | 104 (39.39) | 35 (36.46) | 69 (41.07) | ||

| Rural areas | 160 (60.61) | 61 (63.54) | 99 (58.93) | ||

| Primary caregiver | χ² = 0.02 | 0.901 | |||

| Children | 84 (31.82) | 31 (32.29) | 53 (31.55) | ||

| Spouses | 180 (68.18) | 65 (67.71) | 115 (68.45) | ||

| Payment method | χ² = 0.59 | 0.443 | |||

| Medical insurance | 237 (89.77) | 88 (91.67) | 149 (88.69) | ||

| Self-payment | 27 (10.23) | 8 (8.33) | 19 (11.31) | ||

| Psychological resilience | 62.55 ± 7.27 | 65.52 ± 7.47 | 60.85 ± 6.59 | t = 5.27 | < 0.001 |

| Social support | 43.97 ± 4.99 | 45.16 ± 5.32 | 43.30 ± 4.67 | t = 2.95 | 0.003 |

| Self-perceived burden | 30.24 ± 6.45 | 28.72 ± 6.51 | 31.11 ± 6.27 | t = -2.94 | 0.004 |

Of the patients in the normal group, 46.88% had a duration of illness within 1 year, significantly lower than 61.90% in the FCR group (P = 0.018) (Table 2). The proportion of tumor diameter greater than 5 cm in the normal group was 46.88% and that in the FCR group was 61.90%. The difference was significant (P = 0.020). The incidence of postoperative complications was 11.46% in the normal group and 22.02% in the FCR group, showing a significant difference (P = 0.032).

| Variables | Total (n = 264) | Normal group (n = 96) | FCR group (n = 168) | Statistic | P value |

| Duration of disease | χ² = 5.61 | 0.018 | |||

| ≥ 1 year | 115 (43.56) | 51 (53.12) | 64 (38.10) | ||

| < 1 year | 149 (56.44) | 45 (46.88) | 104 (61.90) | ||

| Tumor diameter | χ² = 5.46 | 0.020 | |||

| < 5 cm | 154 (58.33) | 65 (67.71) | 89 (52.98) | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 110 (41.67) | 31 (32.29) | 79 (47.02) | ||

| Clinical staging | χ² = 2.16 | 0.141 | |||

| Phase I and II | 204 (77.27) | 79 (82.29) | 125 (74.40) | ||

| Phase III and IV | 60 (22.73) | 17 (17.71) | 43 (25.60) | ||

| Pathological type | χ² = 0.09 | 0.770 | |||

| Other | 52 (19.70) | 18 (18.75) | 34 (20.24) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 212 (80.30) | 78 (81.25) | 134 (79.76) | ||

| Multiple foci | χ² = 2.70 | 0.101 | |||

| No | 227 (85.98) | 87 (90.62) | 140 (83.33) | ||

| Yes | 37 (14.02) | 9 (9.38) | 28 (16.67) | ||

| Lesion site | χ² = 0.05 | 0.974 | |||

| Upper part | 89 (33.71) | 33 (34.38) | 56 (33.33) | ||

| Middle part | 82 (31.06) | 30 (31.25) | 52 (30.95) | ||

| Lower part | 93 (35.23) | 33 (34.38) | 60 (35.71) | ||

| H. pylori | χ² = 0.44 | 0.506 | |||

| No | 68 (25.76) | 27 (28.12) | 41 (24.40) | ||

| Yes | 196 (74.24) | 69 (71.88) | 127 (75.60) | ||

| Postoperative complications | χ² = 4.58 | 0.032 | |||

| No | 216 (81.82) | 85 (88.54) | 131 (77.98) | ||

| Yes | 48 (18.18) | 11 (11.46) | 37 (22.02) |

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that older age [odds ratio (OR) = 0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.85-0.95, P < 0.001], higher levels of psychological resilience (OR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.85-0.95, P < 0.001), and social support (OR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.85-0.95, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with a lower risk of FCR (Table 3). In addition, secondary school education and below (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.10-3.08, P = 0.021), a higher level of self-perceived burden (OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1.02-1.10, P = 0.004), duration of disease less than 1 year (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.11-3.06, P = 0.018), tumor diameter greater than 5 cm (OR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.10-3.14, P = 0.020), and postoperative complications (OR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.06-4.51, P = 0.035) were significantly associated with a higher risk of FCR in patients with GC (Table 3).

| Variables | β | SE | Z value | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age | -0.11 | 0.03 | -3.73 | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Male | -0.17 | 0.26 | -0.66 | 0.512 | 0.84 (0.51-1.40) |

| Spouse | |||||

| Yes | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| No | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.67 | 0.501 | 1.28 (0.63-2.60) |

| Educational level | |||||

| High school and above | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 0.61 | 0.26 | 2.30 | 0.021 | 1.84 (1.10-3.08) |

| Household income | |||||

| High income | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Low income | 0.34 | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.195 | 1.40 (0.84-2.32) |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban areas | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Rural areas | -0.19 | 0.26 | -0.74 | 0.461 | 0.82 (0.49-1.38) |

| Primary caregiver | |||||

| Children | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Spouses | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.901 | 1.03 (0.60-1.77) |

| Payment method | |||||

| Medical insurance | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Self-payment | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.444 | 1.40 (0.59-3.34) |

| Psychological resilience | -0.10 | 0.02 | -4.79 | < 0.001 | 0.91 (0.87-0.94) |

| Social support | -0.08 | 0.03 | -2.86 | 0.004 | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

| Self-perceived burden | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.86 | 0.004 | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) |

| Duration of disease | |||||

| ≥ 1 year | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| < 1 year | 0.61 | 0.26 | 2.36 | 0.018 | 1.84 (1.11-3.06) |

| Tumor diameter | |||||

| < 5 cm | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 0.62 | 0.27 | 2.32 | 0.020 | 1.86 (1.10-3.14) |

| Clinical staging | |||||

| Phase I and II | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Phase III and IV | 0.47 | 0.32 | 1.46 | 0.143 | 1.60 (0.85-3.00) |

| Pathological type | |||||

| Others | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | -0.09 | 0.32 | -0.29 | 0.770 | 0.91 (0.48-1.72) |

| Multiple foci | |||||

| No | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 0.66 | 0.41 | 1.62 | 0.105 | 1.93 (0.87-4.29) |

| Lesion site | |||||

| Upper part | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Middle part | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.947 | 1.02 (0.55-1.90) |

| Lower part | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.823 | 1.07 (0.59-1.96) |

| H. pylori | |||||

| No | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.506 | 1.21 (0.69-2.14) |

| Postoperative complications | |||||

| No | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 0.78 | 0.37 | 2.11 | 0.035 | 2.18 (1.06-4.51) |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that older age (OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.83-0.96, P = 0.002), higher level of psychological resilience (OR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.85-0.93, P < 0.001), and social support (OR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.86-0.97, P = 0.006) were independent protective factors for FCR. A high level of self-perceived burden (OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 1.06-1.17, P < 0.001), low level of education (OR = 2.59, 95%CI: 1.35-4.96, P = 0.004), short duration of disease (OR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.05-3.58, P = 0.033), large tumor diameter (OR = 2.24, 95%CI: 1.19-4.20, P = 0.012), and the presence of complications (OR = 3.04, 95%CI: 1.28-7.21, P = 0.012) were independent risk factors for increased risk of FCR in patients with GC (Table 4).

| Variables | β | SE | Z value | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age | -0.11 | 0.04 | -3.15 | 0.002 | 0.89 (0.83-0.96) |

| Psychological resilience | -0.12 | 0.02 | -5.02 | < 0.001 | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) |

| Social support | -0.09 | 0.03 | -2.76 | 0.006 | 0.92 (0.86-0.97) |

| Self-perceived burden | 0.11 | 0.03 | 4.00 | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.06-1.17) |

| Educational level | |||||

| High school and above | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Junior high school and below | 0.95 | 0.33 | 2.87 | 0.004 | 2.59 (1.35-4.96) |

| Duration of disease | |||||

| ≥ 1 year | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| < 1 year | 0.66 | 0.31 | 2.13 | 0.033 | 1.94 (1.05-3.58) |

| Tumor diameter | |||||

| < 5 cm | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| ≥ 5 cm | 0.81 | 0.32 | 2.51 | 0.012 | 2.24 (1.19-4.20) |

| Postoperative complications | |||||

| No | 1.00 (Ref.) | ||||

| Yes | 1.11 | 0.44 | 2.52 | 0.012 | 3.04 (1.28-7.21) |

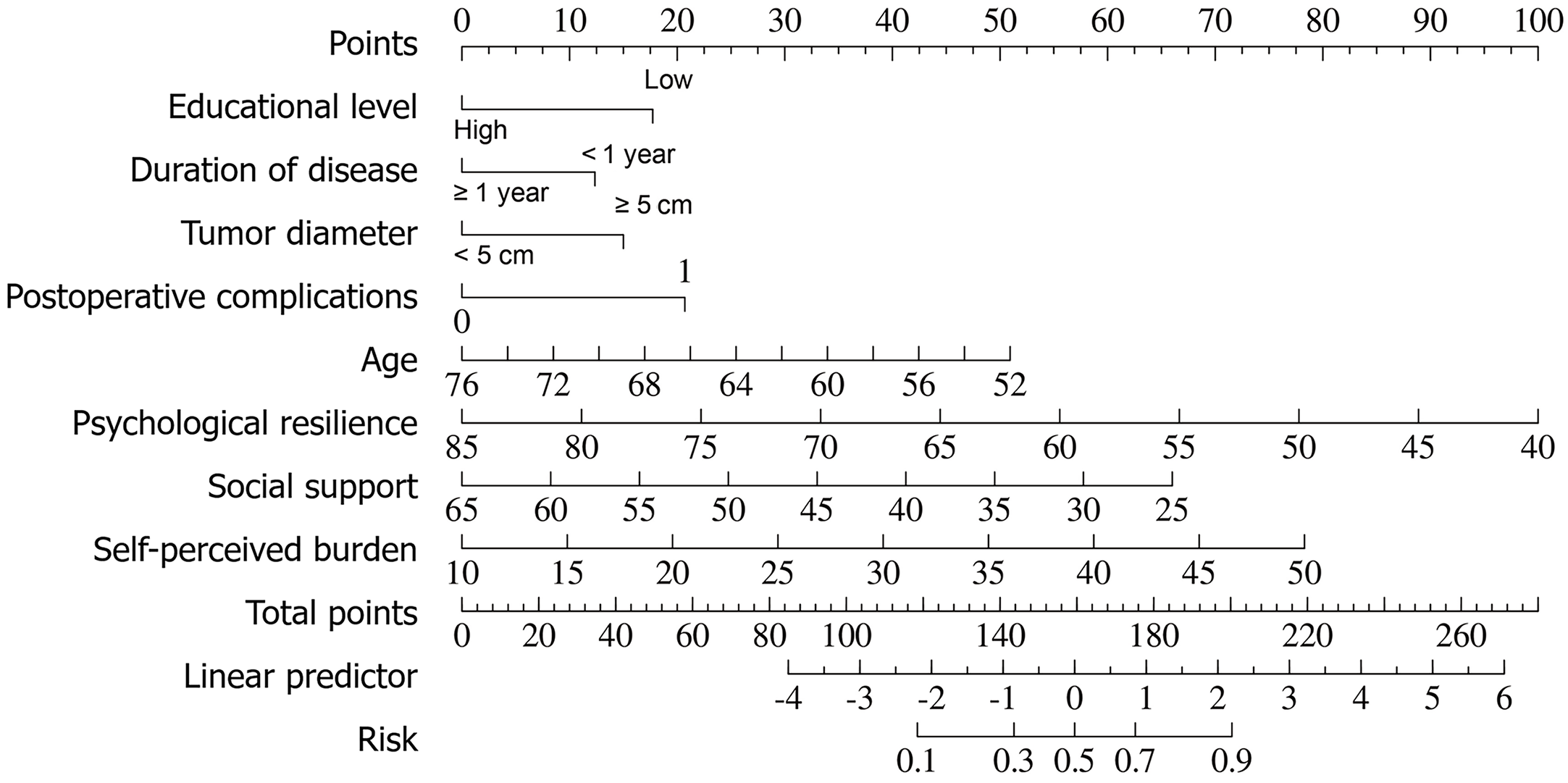

Based on the multivariate logistic results, a nomogram model was constructed to predict the risk of FCR in patients after GC surgery (Figure 1). The model included eight variables: Education level; duration of disease; tumor diameter; postoperative complications; age; psychological resilience; social support; and self-perceived burden.

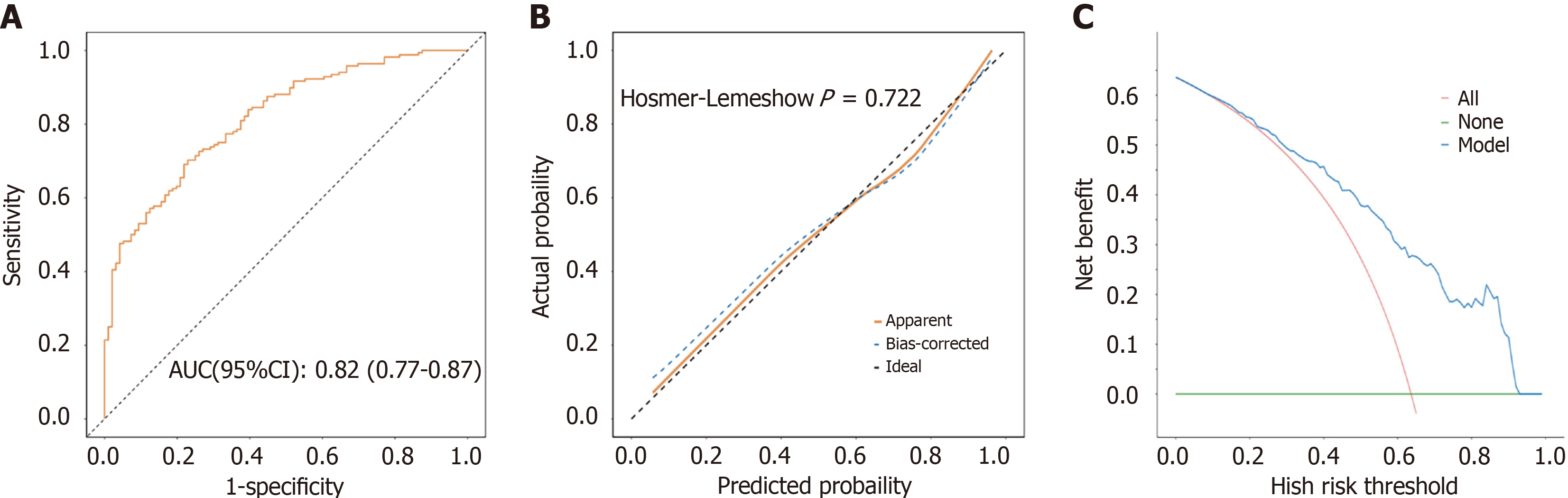

The area under the curve of the receiver operating characteristic curve drawn based on this prediction model was 0.82 (0.77-0.87), indicating that the model had a good degree of differentiation (Figure 2A). The calibration curve and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test (P = 0.722) showed no significant difference between the observed and predicted values, indicating that the model had good calibration (Figure 2B). The decision curve analysis showed that when the threshold probability ranged from 5% to 95%, the column-line model could be used to predict the high-risk population of FCR, and a good net benefit effect could be obtained (Figure 2C). In addition, the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the model were 0.73 (0.67-0.78), 0.77 (0.69-0.85), 0.70 (0.63-0.77), 0.60 (0.51-0.68), and 0.84 (0.78-0.90), respectively (Table 5).

| AUC (95%CI) | Accuracy (95%CI) | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | PPV (95%CI) | NPV (95%CI) | Cutoff |

| 0.82 (0.77-0.87) | 0.73 (0.67-0.78) | 0.77 (0.69-0.85) | 0.70 (0.63-0.77) | 0.60 (0.51-0.68) | 0.84 (0.78-0.90) | 0.659 |

In this study, we analyzed the incidence of FCR in elderly patients with GC and explored its influencing factors. The study revealed that elderly patients with GC typically experienced a considerable degree of FCR following laparoscopic radical surgery. This finding is of significant clinical and societal importance as it not only elucidates the psychological distress of patients during the postoperative recovery period but also provides a theoretical foundation for subsequent interventions. Furthermore, this study identified several factors that contribute to FCR, including age, psychological resilience, social support, self-perceived burden, education level, duration of illness, tumor diameter, and complications. These factors are discussed in detail below.

The results showed that 63.64% of elderly patients with GC had clinically symptomatic FCR. Zhu et al[18] investigated 84 patients with GC and reported that the incidence of FCR was 71.42%. In addition, FCR is prevalent in other cancers and has been reported to have a high incidence[19]. In response to this phenomenon, we analyzed that it may be related to the severity and uncertainty of the cancer itself. As a kind of malignant tumor, the possibility of recurrence and metastasis of GC has always been an unavoidable source of anxiety for patients and their families[20]. In particular, the elderly patient group is susceptible to FCR due to the progressive deterioration of physical capabilities, diminished resilience to illness, and diminished psychological capacity to cope with the disease[21]. Furthermore, surgery, as a traumatic intervention, may result in the removal of the tumor while simultaneously causing physical damage and psychological distress, thereby exacerbating the fear experienced by patients.

In examining the protective factors associated with FCR, our findings revealed that older age, elevated levels of psychological resilience, and augmented levels of social support exerted a notable positive influence. This finding may be related to the level of health concerns and perceptions of disease in older adults. In a study of 965 patients with breast cancer, Schapira et al[22] observed a reduction in FCR levels over time[22]. As age and the duration of illness increase, individuals may become more cognizant of their health concerns and consequently engage in more proactive health management strategies, such as regular check-ups and the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits. These actions may potentially mitigate their apprehension about cancer recurrence[23].

Patients with high psychological resilience are more inclined to adopt positive coping strategies to face the challenges posed by the disease. Those who have undergone treatment for cancer are better able to cope with the negative emotions associated with the disease, such as anxiety and depression. These emotions are significant predictors of FCR[24]. Individuals with higher psychological resilience usually have better emotional regulation and are able to self-regulate their psychological state to form a favorable internal environment that enhances cellular immunity and strengthens their ability to resist disease. This ability to regulate emotions helps to reduce the FCR[25].

Furthermore, social support, encompassing emotional and practical assistance, can offer patients a sense of emotional solace and mitigate feelings of loneliness and helplessness. The provision of emotional support serves to mitigate the patient’s anxiety and fear, thereby reducing FCR[26]. The provision of social support can enhance the quality of life of patients, which in turn can facilitate a reduction in FCR. The presence of positive social support can assist patients in adapting to their circumstances more effectively, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of the disease[27].

Furthermore, this study also identified several risk factors for FCR, including high levels of self-perceived burden, lower education, shorter duration of illness, larger tumor diameter, and the presence of comorbidities. The term “self-perceived burden” is used to describe the patient’s perception that they have become a burden to their family or a liability to society as a result of their illness. This psychological burden can have a significant impact on the patient’s emotional state and may lead to a reduction in their motivation and effectiveness in anticancer treatment and can increase the level of FCR[28]. In addition, patients with higher self-perceived burden may have more difficulty seeking and receiving social support, further exacerbating FCR.

Patients with lower levels of education may be less able to access and understand health information and could lead to increased uncertainty about the disease and the course of treatment This uncertainty is an important predictor of FCR because it increases patients’ worry and fear of disease recurrence[29]. In addition, patients with a shorter duration of illness exhibited higher levels of FCR. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that newly diagnosed patients possess limited knowledge about the disease and its treatment. Consequently, their fear of the unknown may heighten FCR. Over time as patients acclimatize to the disease and gain a better understanding of both the disease and treatment options, their levels of FCR tend to decrease.

Tumor diameter is an important indicator of prognosis in GC, and larger tumor diameters are usually associated with a poorer prognosis. Therefore, patients with larger tumor diameters may have a more pessimistic expectation of their prognosis, which may lead to an increased FCR[30]. Finally, patients with comorbidities have higher levels of FCR. Complications may increase patients’ physical discomfort and treatment complexity, thereby increasing FCR. In addition, comorbidities may lead to decreased patient confidence in treatment, further exacerbating FCR[31].

In summary, this study revealed multiple factors that influenced FCR in elderly patients with GC. They relate to an individual’s psychological state, social environment, and disease characteristics. In clinical practice aid can be given to patients to improve their psychological resilience and enhance their ability to cope with FCR through the provision of psychological counselling, psychoeducation, social support groups, etc. Meanwhile, strengthening family and social support for patients can also effectively reduce their FCR level and improve their quality of life. In addition, more personalized interventions should be developed for high-risk patients with low education levels, short disease duration, large tumor diameters, and the presence of complications to reduce their FCR levels.

The nomogram model developed in this study can provide clinicians with a practical tool for assessing the risk of FCR after surgery in elderly patients with GC. Clinicians can quickly identify high-risk patients through a simple scoring system and target psychological interventions and social support. In order to effectively integrate the tool into routine clinical practice, the following preparations are needed: (1) Development of an electronic scoring system to facilitate rapid calculation and recording; (2) Training of healthcare professionals to ensure that they are able to use the tool accurately; and (3) Establishment of a mechanism for multidisciplinary teamwork to ensure that identified high-risk patients receive appropriate psychological and social support in a timely manner.

Nevertheless, there were some limitations to this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow causality to be established; only correlation can be observed. Secondly, although the study included patients from four medical centers, the sources of the sample remain limited and may limit the generalizability of the results. In addition, the data collection in this study relied mainly on patients’ self-reports, which may be affected by recall bias or subjectivity. Finally, although the nomogram model is of statistically significant value, its clinical utility is equally critical.

To overcome these limitations, future studies can consider the following aspects. First, the sample size should be expanded to include more patients from different regions and hospitals to improve the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Second, a longitudinal design should be adopted to follow the dynamic development of the changes in patients’ FCR and their influencing factors in order to explore the intrinsic mechanisms in more depth. Third, multidisciplinary biological, genetic, and other perspectives should be combined to further reveal the biological basis and genetic susceptibility of FCR. Finally, in future studies we will plan to conduct an experimental study to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the nomogram model in a real-world clinical setting. This will include working with clinicians to understand how they are using the tool as well as identifying the resources and support needed to implement it.

This study revealed the prevalence of higher levels of FCR in elderly patients with GC after undergoing laparoscopic radical surgery and identified key factors influencing FCR, including age, psychological resilience, social support, self-perceived burden, education level, disease duration, tumor size, and comorbidities. The findings emphasized the significance of psychological and social support in mitigating FCR and suggest that future treatments should optimize these support measures to enhance patient quality of life. Furthermore, the study recommended the development of targeted psychological interventions and calls for the use of multiple data sources in future studies to enhance the objectivity of the results.

We sincerely thank all the medical staff involved in this study for their help and support and all the patients for their understanding and support.

| 1. | López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, Quispe L, Zevallos A, Buleje JL, Cho CE, Sarmiento M, Pinto JA, Fajardo W. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;181:103841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12803] [Article Influence: 6401.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 3. | Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134:783-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1624] [Cited by in RCA: 2008] [Article Influence: 401.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Ju W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Sun K, Wang S, Chen R, Li L, Wei W, He J. Cancer statistics in Chinese older people, 2022: current burden, time trends, and comparisons with the US, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Sci China Life Sci. 2023;66:1079-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Joshi SS, Badgwell BD. Current treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:264-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 1194] [Article Influence: 238.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 6. | Chen WZ, Yu DY, Zhang XZ, Zhang FM, Zhuang CL, Dong QT, Shen X, Yu Z. Comparison of laparoscopic and open radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients with GLIM-defined malnutrition. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2023;49:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Romero-Peña M, Suarez L, Valbuena DE, Rey Chaves CE, Conde Monroy D, Guevara R. Laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective analysis in Colombia. BMC Surg. 2023;23:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Berlin P, von Blanckenburg P. Death anxiety as general factor to fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2022;31:1527-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luigjes-Huizer YL, Tauber NM, Humphris G, Kasparian NA, Lam WWT, Lebel S, Simard S, Smith AB, Zachariae R, Afiyanti Y, Bell KJL, Custers JAE, de Wit NJ, Fisher PL, Galica J, Garland SN, Helsper CW, Jeppesen MM, Liu J, Mititelu R, Monninkhof EM, Russell L, Savard J, Speckens AEM, van Helmondt SJ, Vatandoust S, Zdenkowski N, van der Lee ML. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2022;31:879-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 51.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prins JB, Deuning-Smit E, Custers JAE. Interventions addressing fear of cancer recurrence: challenges and future perspectives. Curr Opin Oncol. 2022;34:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Paperák P, Javůrková A, Raudenská J. Therapeutic intervention in fear of cancer recurrence in adult oncology patients: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2023;17:1017-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. [Fear of progression in breast cancer patients--validation of the short form of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF)]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006;52:274-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu QY, Ye ZX, Li L, Liu PY. [Sinicisation and Reliability Analysis of the Simplified Scale of Fear of Disease Progression for Cancer Patients]. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2015;50:1515-1519. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4591] [Cited by in RCA: 5646] [Article Influence: 256.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zou Z, Wang Z, Herold F, Kramer AF, Ng JL, Hossain MM, Chen J, Kuang J. Validity and reliability of the physical activity and social support scale among Chinese established adults. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023;53:101793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cousineau N, McDowell I, Hotz S, Hébert P. Measuring chronic patients' feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med Care. 2003;41:110-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tang XY. [A study of the effectiveness of supportive psychotherapy in improving self-perceived burden in cancer patients]. M.Sc. Thesis, Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, 2010. |

| 18. | Zhu X, Ren G, Wang J, Yan Y, Du X. A multiple linear regression analysis identifies factors associated with fear of cancer recurrence in postoperative patients with gastric cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e35110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hu X, Wang W, Wang Y, Liu K. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients with multiple myeloma: Prevalence and predictors based on a family model analysis. Psychooncology. 2021;30:176-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Loughan AR, Lanoye A, Aslanzadeh FJ, Villanueva AAL, Boutte R, Husain M, Braun S. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Death Anxiety: Unaddressed Concerns for Adult Neuro-oncology Patients. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28:16-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tang M, Su Z, He Y, Pang Y, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Lu Y, Jiang Y, Han X, Song L, Wang L, Li Z, Lv X, Wang Y, Yao J, Liu X, Zhou X, He S, Zhang Y, Song L, Li J, Wang B, Tang L. Physical symptoms and anxiety and depression in older patients with advanced cancer in China: a network analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schapira L, Zheng Y, Gelber SI, Poorvu P, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Peppercorn J, Come SE, Borges VF, Partridge AH, Rosenberg SM. Trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2022;128:335-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Cho H, Kim NY, Shim S, Kim HY, Kang D, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H. Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Its Negative Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life in Long-term Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54:1065-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Podina IR, Todea D, Fodor LA. Fear of cancer recurrence and mental health: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2023;32:1503-1513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zábó V, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Purebl G. Psychological resilience and competence: key promoters of successful aging and flourishing in late life. Geroscience. 2023;45:3045-3058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang X, Dong S. The relationships between social support and loneliness: A meta-analysis and review. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2022;227:103616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shen T, Li D, Hu Z, Li J, Wei X. The impact of social support on the quality of life among older adults in China: An empirical study based on the 2020 CFPS. Front Public Health. 2022;10:914707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Saji A, Oishi A, Harding R. Self-perceived Burden for People With Life-threatening Illness: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023;65:e207-e217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Han M, Chen H, Li J, Zheng X, Zhang X, Tao L, Zhang X, Feng X. Correlation between symptom experience and fear of cancer recurrence in postoperative breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in China: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0308907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chen L, Yue C, Li G, Ming X, Gu R, Wen X, Zhou B, Peng R, Wei W, Chen H. Clinicopathological features and risk factors analysis of lymph node metastasis and long-term prognosis in patients with synchronous multiple gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yu H, Xu L, Yin S, Jiang J, Hong C, He Y, Zhang C. Risk Factors and Prognostic Impact of Postoperative Complications in Patients with Advanced Gastric Cancer Receiving Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:6496-6507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/