Published online May 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.104043

Revised: February 14, 2025

Accepted: March 12, 2025

Published online: May 27, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 5.6 Hours

Despite advancements, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) poses challenges, including the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis and difficulty of biliary cannulation.

To compare dome and tapered tip sphincterotomes, focusing on their efficacy in achieving successful biliary cannulation and reducing the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

In this prospective, single-blind, randomized pilot study conducted at Inha Uni

The success rates of selective biliary cannulation were 74.4% and 85.7% in the dome and tapered tip groups, respectively, with no significant difference (P = 0.20). Similarly, the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis did not differ significantly between the groups (5 cases in the tapered tip group vs 6 in the dome tip group, P = 0.72). However, difficult cannulation was significantly more common in the dome tip group than in the tapered tip group (P = 0.05). Selective biliary cannula

This study indicated that the sphincterotome tip type does not markedly affect biliary cannulation success or post-ERCP pancreatitis rates. However, cannulation duration is a key risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis. These findings provide preliminary insights that highlight the importance of refining ERCP practices, including sphincterotome selection, while underscoring the need for larger multicenter studies to improve procedure time and patient safety.

Core Tip: This pilot study compared dome and tapered tip sphincterotomes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), with focus on selective biliary cannulation success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Although cannulation success and pancreatitis rates did not differ significantly between the two tip types, a prolonged cannulation time was a key predictor of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The tapered tip group encountered fewer cannulation difficulties, suggesting a maneuverability advantage. These findings underscore the importance of minimizing cannulation time and support the need for larger multicenter studies to refine ERCP practices and improve patient safety.

- Citation: Lee J, Park JS. Dome vs tapered tip sphincterotomes in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A pilot study on cannulation success and postprocedural pancreatitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(5): 104043

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i5/104043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.104043

Since the initial introduction of endoscopic cholangiography and the subsequent development of the first endoscopic sphincterotomy over five decades ago, the practice of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) alongside biliary sphincterotomy was accepted as a safe, direct technique for evaluating pancreaticobiliary diseases[1,2]. It has been recognized as a standard diagnostic and therapeutic intervention for biliary diseases. Over time, the scope of ERCP and its therapeutic impact have broadened substantially, now encompassing a wide spectrum of pathologies within the pan

Precise cannulation of the common bile duct via the ampulla of Vater is essential for a successful ERCP. Nonetheless, this procedure is frequently challenged by two main issues: Failure to accomplish biliary cannulation and occurrence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Regrettably, even for highly skilled specialists, the success rate of conventional bile duct cannu

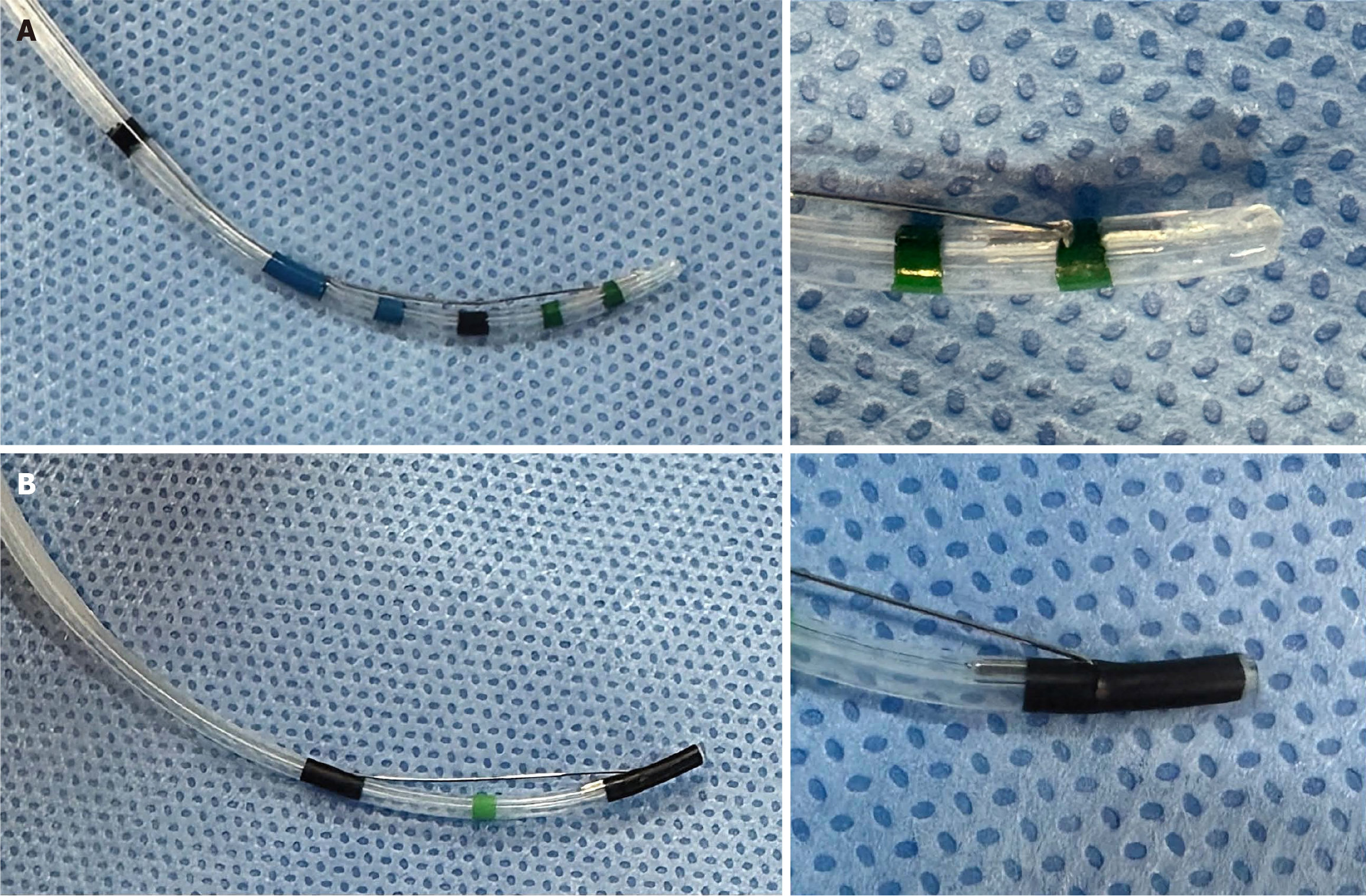

The tools used for cannulation are categorically divided into cannulation catheters, sphincterotomes (also known as papillotomes), and access (precut) papillotomy catheters[8]. Despite the array of available devices, an optimal approach for safe and effective cannulation is yet to be definitively established[9-11]. Within this spectrum of techniques, sphincterotome-assisted cannulation is frequently recognized as an effective strategy for securing biliary access[8,12]. Sphincterotomes, typically tapered and occasionally dome-shaped, ranging from 3.5 to 5.5 Fr, facilitate duct system access[13]. The dome tip sphincterotome, designed with a smooth hemispherical end similar to that of an egg, ensures gentle cannulation with minimal tissue damage[14]. Despite the widespread use of sphincterotomes, there is a notable lack of prospective studies exploring the impact of the device tip shape on cannulation success rates or the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of dome- and tapered tip sphincterotomes in achieving successful selective biliary cannulation and reducing the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

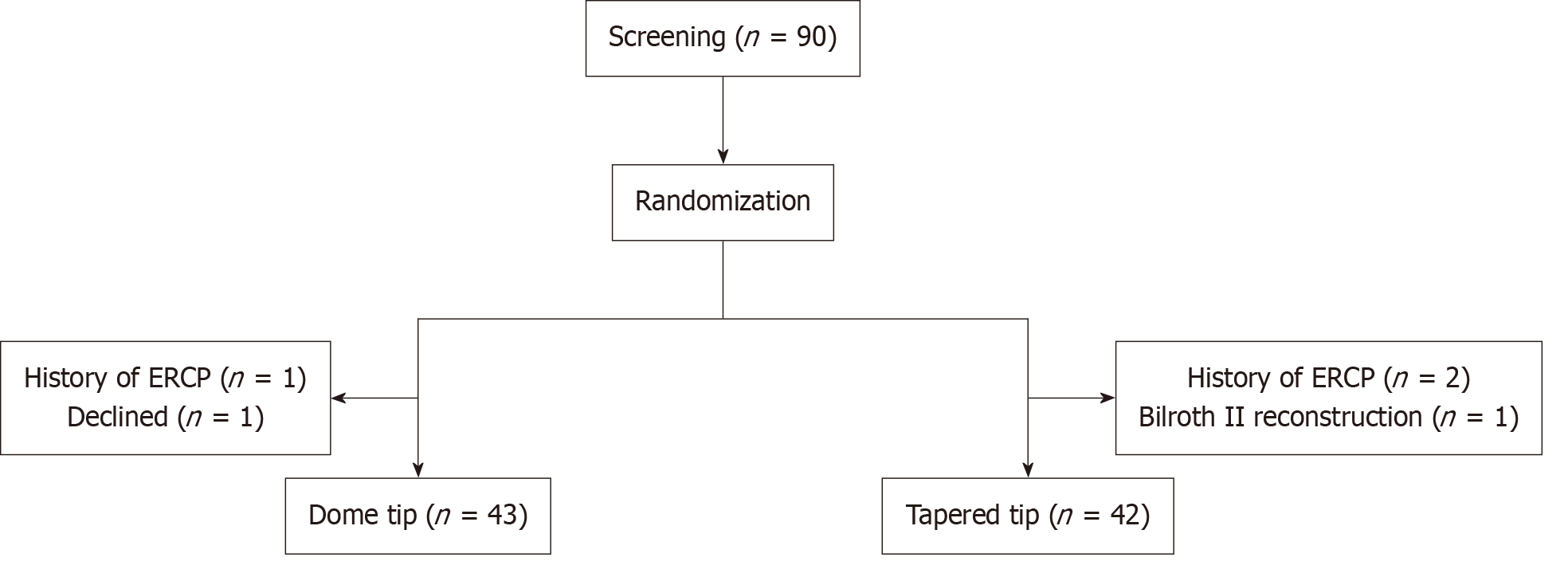

This prospective, single-blind, randomized, single-center pilot study was conducted to assess and compare the efficacy and safety of dome and tapered tip sphincterotomes in patients undergoing ERCP. The patients were recruited between February 2023 and February 2024. Eighty-five patients that underwent diagnostic or therapeutic biliary ERCP were equally randomized to a dome tip or tapered tip sphincterotome arm. A schematic of the study design is shown in Figure 1.

All patients were recruited from Inha University Hospital (a Korean tertiary referral hospital). During the study period, all eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively enrolled. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) Age > 18 years; (2) Scheduled for a diagnostic or therapeutic biliary ERCP; and (3) Provision of voluntary informed consent. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) History of ERCP-related procedures; (2) Scheduled for a diagnostic or therapeutic pancreatic ERCP; (3) Acute pancreatitis; (4) History of abdominal surgery and Billroth II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction; (5) Pregnancy; (6) Coagulopathy; or (7) Serious cardiopulmonary disease. Parti

In this study, each ERCP was conducted by an expert endoscopist with at least a decade of experience and who performed up to 500 ERCPs annually. The procedures were performed using a TJF-Q290V side-viewing duodenoscope (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). The initiation involved navigating the duodenoscope to the second part of the duodenum, with patients sedated using 5 mg intravenous remimazolam, ensuring optimal comfort and safety under conscious sedation. Upon securing the duodenoscope in an optimal position for visualizing the papilla of Vater, cannu

The primary outcomes were the technical success rate of selective biliary cannulation and occurrence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The secondary outcomes included the rate of difficult biliary cannulation, duration of biliary cannulation, frequency of unintended pancreatic duct access, and number of attempts made to cannulate the papilla. Difficult biliary cannulation is indicated by any of the following situations: The cannulation attempt continues for over 5 minutes; there are more than five contacts made with the papilla, or there is more than one unintended cannulation or opacification of the pancreatic duct[15]. Unintended pancreatic access was defined as the total number of instances of contrast medium injection or guidewire entry into the pancreatic duct. Successful biliary cannulation was characterized by the ability to navigate and instrument the biliary tree freely and deeply within a 5-minute timeframe. The time to selective biliary cannulation was defined as the time required for biliary cannulation, calculated from the moment the sphincterotome or guidewire initially contacted the papilla of Vater to the point of successful cannulation. The total procedure time was defined as the duration from side-viewing duodenoscope insertion into the patient to duodenoscope removal. When access to the bile duct was not achieved within 5 minutes using either a dome or tapered tip sphincterotome, rescue cannulation techniques such as precut and pancreatic duct guidewire placement were employed. The diagnosis of post-ERCP pancreatitis was based on the criteria established by Cotton et al[16].

The clinical characteristics of the study participants are expressed as means ± SDs for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. The significance of the differences between the dome and tapered tip groups was determined using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables or the χ2 test for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was used to compare the co-primary endpoints between the two groups, and univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify potential risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis. The analysis was performed using SPSS v19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (INHAUH 2022-10-008), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the commencement of the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

Of the 90 patients screened for ERCP, 45 were initially allocated to the dome tip group and 45 to the tapered tip group. Following randomization, the groups were revised based on the exclusion criteria and participant withdrawal, resulting in 43 patients in the dome tip group and 42 in the tapered tip group (Table 1). The median age in the dome tip group was 72 years (range 32-91), whereas that in the tapered tip group was 71 years (range 32-92), with no significant difference (P = 0.59). The sex composition was comparable, with 15 males and 30 females in the dome tip group and 19 males and 26 females in the tapered tip group, which was not significantly different (P = 0.12). Body mass index was similar between the groups, with the dome tip group averaging 24.06 ± 4.79 and the tapered tip group averaging 24.81 ± 4.03 (P = 0.81). Regarding the indications for ERCP, 11 patients in the dome tip group and 7 in the tapered tip group presented with malignant conditions, including pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, and other cancers. Benign conditions, including choledocholithiasis and benign biliary strictures, were observed in 34 patients in the dome tip group and in 38 patients in the tapered tip group. There was no significant difference in the distribution of malignant and benign conditions between the groups (P = 0.4) (Table 1).

| Variables | Dome tip (n = 45) | Tapered tip (n = 45) | P value1 |

| Age, year (median, min-max) | 72 (32-91) | 71 (32-92) | 0.59 |

| Age ≥ 65 | 30 (66.7) | 26 (57.8) | |

| Age < 65 | 15 (33.3) | 19 (42.2) | |

| Sex | 0.12 | ||

| Male | 15 (33.3) | 19 (42.2) | |

| Female | 30 (66.7) | 26 (57.8) | |

| BMI | 24.06 ± 4.79 | 24.81 ± 4.03 | 0.81 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 12 (26.7) | 21 (46.7) | |

| BMI < 25 kg/m2 | 33 (73.3) | 24 (53.3) | |

| Indications (malignant/benign) | 0.4 | ||

| Malignant | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 5 (11.1) | 5 (11.1) | |

| Other cancers | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Benign | |||

| Choledocholithiasis | 32 (71.1) | 34 (75.6) | |

| Benign biliary stricture | 2 (4.4) | 4 (8.9) |

In this study, ERCP patients were allocated to either the dome tip or tapered tip sphincterotome group to evaluate the success of selective biliary cannulation. The success rates of the 85 participants were 74.4% in the dome tip group and 85.7% in the tapered tip group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = 0.20). However, the tapered tip group experienced significantly fewer difficult cannulations, defined by over five contacts with the papilla or attempts lasting longer than 5 minutes, with a rate of 14.3% compared with 32.6% in the dome tip group (P = 0.05). The mean times to achieve cannulation were comparable between the groups (P = 0.43), with the dome tip at 237.74 ± 252.36 seconds and the tapered tip at 188.7 ± 319.96 seconds. The number of papilla contacts showed no significant difference either, with 3.03 ± 2.45 contacts for the dome tip and 2.24 ± 2.17 for the tapered tip (P = 0.37). Similarly, unintentional pancreatic duct cannulation was infrequent and statistically similar in both the groups (P = 0.53). The total procedure time was somewhat shorter for the tapered tip group, at 808 ± 409.57 seconds vs 971.16 ± 367.13 seconds for the dome tip group, which approached but did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.06) (Table 2). In cases where bile duct access was not achieved within 5 minutes, 7 out of 11 patients in the dome tip arm resorted to using a tapered tip sphincterotome, whereas in the tapered tip arm, 2 out of 6 patients switched to a dome tip. The choice of sphincterotome for rescue cannulation did not differ significantly between the groups (P = 0.34). For the pancreatic duct guidewire technique and precut sphincterotomy, preferences for rescue methods were similarly non-significant between the groups (P = 0.60 and P = 0.59, respectively) (Table 3).

| Variables | Dome tip (n = 43) | Tapered tip (n = 42) | P value1 |

| Selective biliary cannulation success rate | 32/43 | 36/42 | 0.20 |

| Difficult cannulation | 14/43 | 6/42 | 0.05 |

| More than 5 contacts with the papilla | 5 | 2 | 0.93 |

| More than 5 minutes spent attempting | 11 | 6 | 0.08 |

| More than one unintended pancreatic duct cannulation or opacification | 3 | 2 | 0.62 |

| Time to selective biliary cannulation (seconds) | 237.74 ± 252.36 | 188.7 ± 319.96 | 0.43 |

| Number of papilla contacts | 3.03 ± 2.45 | 2.24 ± 2.17 | 0.37 |

| Number of unintentional P duct cannulation | 0.47 ± 0.63 | 0.38 ± 0.58 | 0.53 |

| Total procedure time (seconds) | 971.16 ± 367.13 | 808 ± 409.57 | 0.06 |

In the assessment of post-ERCP complications, the rate of pancreatitis following the procedure was recorded in both the tapered and dome tip groups. The tapered tip group exhibited post-ERCP pancreatitis in five cases, whereas the dome tip group reported six cases. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.72), indicating that the shape of the sphincterotome tip did not have a measurable impact on the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Additionally, neither group reported instances of post-ERCP bleeding or perforation, suggesting a consistent safety profile for these specific complications between the two techniques (Table 4). All 11 patients who developed post-ERCP pancreatitis were diagnosed with mild acute pancreatitis according to the Atlanta Classification System[17]. These patients showed im

In the exploration of factors predictive of post-ERCP pancreatitis through both univariate and multivariate analyses, we found that demographics such as age, sex, body mass index, nature of the condition (whether malignant or benign), type of sphincterotome used (dome vs tapered) and the use of rescue cannulation techniques were not significantly associated with the developing pancreatitis after ERCP. Notably, the time spent on selective biliary cannulation was identified as a crucial predictor of an increased risk of pancreatitis, with marked significance observed in the univariate analysis (odds ratio = 14.00, P < 0.001), and significance was maintained after adjustment in the multivariate model (odds ratio = 9.33, P = 0.03). Although the overall duration of the ERCP procedure was initially found to be significant, its impact diminished in the multivariate analysis. The number of attempts to contact the papilla with contrast was shown to have a protective effect in the univariate model; however, this significance was not maintained in further analysis. Lastly, the incidence of unintentional pancreatic duct cannulation was not significantly associated with the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis (Table 5).

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value1 | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value1 | |

| Age | 0.48 | 0.13-1.72 | 0.26 | |||

| Sex | 1.75 | 0.47-6.49 | 0.40 | |||

| BMI | 2.09 | 0.58-7.50 | 0.26 | |||

| Malignant/benign | 0.95 | 0.18-4.90 | 0.95 | |||

| Dome tip vs tapered tip | 1.27 | 0.36-4.52 | 0.72 | |||

| Time to selective biliary cannulation | 14.00 | 2.77-70.86 | 0.00 | 9.33 | 1.31-66.44 | 0.03 |

| Time to ERCP procedure | 6.98 | 1.41-34.64 | 0.02 | 3.23 | 0.50-20.80 | 0.22 |

| Number of contrast papilla contact | 0.18 | 0.04-0.74 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.14-6.94 | 1.00 |

| Number of unintentional P duct cannulation | 0.43 | 0.12-1053 | 0.19 | |||

| Rescue cannulation | 2.68 | 0.68-10.52 | 0.16 | |||

Our study assessed the impact of sphincterotome tip type on ERCP outcomes by specifically examining the relative efficacy of dome and tapered tip devices in routine practice. Our comparative analysis revealed no significant difference in the success rate of selective biliary cannulation or in the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis between the two sphincterotome types. Although the success rate of biliary cannulation was higher in the tapered tip group (85.7%) than in the dome tip group (74.4%), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.20). The lack of statistical significance could be attributed to the relatively small sample size (n = 85) of the study. Furthermore, one of the study’s primary endpoints, incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis, showed no significant variation between the groups, with the tapered tip group experiencing 5 cases and the dome tip group experiencing 6 cases (P = 0.72). However, interestingly, in the analysis of ERCP outcomes, the incidence of difficult cannulation was significantly higher in the group using dome tip sphincterotomes (P = 0.05). This suggests that the slender end of the tapered tip may facilitate finer manipulation, improving ease of cannulation. In addition, the time required to achieve selective biliary cannulation was identified as a critical factor influencing the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The data revealed that prolonged duration of the cannulation process significantly increased the likelihood of developing pancreatitis, with a multivariate odds ratio of 9.33 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.31-66.44, P = 0.03]. Our findings emphasize the critical role of minimizing biliary cannulation time as a strategy to mitigate the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

All ERCP procedures commence with the selective cannulation of the bile or pancreatic duct, which is a pivotal step that significantly influences the success of the procedure. Successful ERCP requires deep cannulation of the common bile duct through the papilla of Vater. Cannulating the major papilla can pose challenges, with reports indicating that selec

Post-ERCP pancreatitis is a substantial adverse event, affecting approximately 8% of patients at average risk and escalating to 15% among those at higher risk, thereby representing a major complication in gastrointestinal endoscopy practice[21,22]. The genesis of this condition is attributed to a complex interplay of mechanical, thermal, and chemical stressors on the pancreatic duct and papilla, initiating an inflammatory cascade that can lead to severe systemic complications, including mortality rate of 1 in 500[21-23]. Innovations such as pancreatic stents, rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and aggressive hydration strategies have been developed to mitigate such risks; however, their application in clinical practice is often impeded by patient comorbidities, particularly in settings such as Korea, where certain inter

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size of approximately 45 participants per group, although sufficient for a pilot study, limited the statistical power of our findings and may not fully reflect the broader patient population, thereby affecting the generalizability of our results. Additionally, the pilot design implied a preliminary exploration rather than conclusive evidence, highlighting the need for confirmatory research. Second, the relatively small number of post-ERCP pancreatitis cases (n = 11) led to wide CIs in our statistical analysis, suggesting potential overfitting. Further investigations with a wider patient base would help refine the role of cannulation time as a predictor of post-ERCP pancreatitis and validate these initial observations. Furthermore, the study did not account for variations in anatomical challenges among patients, such as differences in bile duct anatomy or the presence of pancreaticobiliary diseases, which could affect the ease of cannulation, and consequently, the procedure time. Additionally, our focus on the selective biliary cannulation success rate and incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis as co-primary outcomes does not encompass other critical factors such as patient-reported outcomes, endoscopist’s subjective assessment, and medical costs. Although the above primary outcomes are essential aspects of successful ERCP procedures, a comprehensive evaluation of sphincterotome performance should consider these additional outcomes to provide a more holistic understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of dome tip vs tapered tip sphincterotomes. Another limitation was that the study was conducted by a single expert practitioner. While this approach ensured consistency in the technique and potentially minimized the variability in procedure times across cases, it also introduced a caveat when generalizing the findings. ERCP cannulation is a technically demanding procedure, and operator skill can significantly affect the outcomes. As the study’s results are based on the practice of a single expert, extrapolating these results to a broader community of practitioners with varying levels of expertise and experience may not be straightforward. Future studies could include mul

In conclusion, this pilot study highlights the minimal impact of sphincterotome tip design on successful biliary cannula

| 1. | McCune WS, Shorb PE, Moscovitz H. Endoscopic cannulation of the ampulla of vater: a preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1968;167:752-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Classen M, Demling L. [Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author's transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adler DG, Baron TH, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J, Faigel DO; Standards of Practice Committee of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. ASGE guideline: the role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chathadi KV, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Decker GA, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, Evans JA, Faulx AL, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley K, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Sharaf R, Shaukat A, Shergill AK, Wang A, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of ERCP in benign diseases of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:795-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | El Chafic AH, Shah JN. Advances in Biliary Access. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Peng C, Nietert PJ, Cotton PB, Lackland DT, Romagnuolo J. Predicting native papilla biliary cannulation success using a multinational Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) Quality Network. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Williams EJ, Ogollah R, Thomas P, Logan RF, Martin D, Wilkinson ML, Lombard M. What predicts failed cannulation and therapy at ERCP? Results of a large-scale multicenter analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | ASGE Technology Committee; Kethu SR, Adler DG, Conway JD, Diehl DL, Farraye FA, Kantsevoy SV, Kaul V, Kwon RS, Mamula P, Pedrosa MC, Rodriguez SA, Tierney WM. ERCP cannulation and sphincterotomy devices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:435-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Maydeo A, Borkar D. Techniques of selective cannulation and sphincterotomy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:S19-S23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laasch HU, Tringali A, Wilbraham L, Marriott A, England RE, Mutignani M, Perri V, Costamagna G, Martin DF. Comparison of standard and steerable catheters for bile duct cannulation in ERCP. Endoscopy. 2003;35:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schwacha H, Allgaier HP, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Allgaier U, Blum HE. A sphincterotome-based technique for selective transpapillary common bile duct cannulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Manes G. Biliary sphincterotomy techniques. In: Frontiers of Gastrointestinal Research. Switzerland: Karger International, 2010: 319-327. |

| 14. | Lee TY. Recent Update of Accessories for ERCP. Korean J Pancreas Biliary Tract. 2021;26:77-84. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Testoni PA, Mariani A, Aabakken L, Arvanitakis M, Bories E, Costamagna G, Devière J, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Dumonceau JM, Giovannini M, Gyokeres T, Hafner M, Halttunen J, Hassan C, Lopes L, Papanikolaou IS, Tham TC, Tringali A, van Hooft J, Williams EJ. Papillary cannulation and sphincterotomy techniques at ERCP: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:657-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2080] [Article Influence: 59.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4669] [Article Influence: 359.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 18. | Tse F, Liu J, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, Leontiadis GI. Guidewire-assisted cannulation of the common bile duct for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;3:CD009662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, Riley SA, Veitch P, Wilkinson M, Williamson PR, Lombard M; BSG Audit of ERCP. Are we meeting the standards set for endoscopy? Results of a large-scale prospective survey of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatograph practice. Gut. 2007;56:821-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Byrne KR, Adler DG. Cannulation of the major and minor papilla via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Techniques and outcomes. Tech Gastrointest En. 2012;14:135-140. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, Elmunzer BJ, Kim KJ, Lennon AM, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-149.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ohshio G, Saluja A, Steer ML. Effects of short-term pancreatic duct obstruction in rats. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:196-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mäkelä A, Kuusi T, Schröder T. Inhibition of serum phospholipase-A2 in acute pancreatitis by pharmacological agents in vitro. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |