Published online May 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.103194

Revised: March 13, 2025

Accepted: April 15, 2025

Published online: May 27, 2025

Processing time: 192 Days and 6.2 Hours

Complications arising from the polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) have historically been addressed through surgical treatment. Enteroscopic poly

To investigate the natural surgical risks associated with polyps in PJS and to clarify their age distribution.

A web-based open survey was launched to collect information from Chinese individuals suspected of having PJS. The questionnaire was distributed to the PJS instant messaging groups using a quick response code method. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods, and the cumulative incidence of surgery was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Of the 442 patients enrolled, 301 (68.10%) had undergone 506 surgical procedures prior to enteroscopy or the survey deadline. Among the 506 surgical procedures, 388 (76.68%) were performed on patients aged between 6 and 25 years. The cumulative incidence rates of the first surgical procedure at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 years of age were 5.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.9%-7.0%), 20.6% (95%CI: 16.6%-24.4%), 40.5% (95%CI: 35.5%-45.1%), 58.0% (95%CI: 52.7%-62.7%), 72.6% (95%CI: 67.3%-77.0%), and 82.4% (95%CI: 77.0%-86.5%), respectively. The primary indications for the first surgical procedures were intussusception (81.40%), obstruction (13.95%), and gas

Chinese patients with PJS have a high natural risk of undergoing surgery. Without preventive intervention, these procedures may become necessary at an early age and may be repeated. Early screening and regular surveillance, with preventive intervention if necessary, should commence at six years of age.

Core Tip: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare disorder characterized by the presence of multiple intestinal polyps, which can lead to intussusception and often require surgery. Screening and preventive intervention for polyps in PJS may reduce the need for surgery. However, most guidelines regarding screening for polyps in PJS are based on expert opinion. This large sample survey demonstrated that patients with PJS exhibit markedly elevated natural surgical risks, particularly between the ages of 6 and 25 years. In light of these findings, we recommend that screening, surveillance, and preventive interventions if indicated, should commence at six years of age. We posit that our strategy based on natural surgical risk is more cost-effective and represents an optimal balance between preventing polyp-related complications and avoiding over-screening.

- Citation: Xiao NJ, Liu S, Han ZY, Zhang TZ, Jiang ZM, Sun T, Zhang J, Wang L, Ning SB, Li W. Natural surgical risks and age distribution in Chinese patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Real-world research based on a web survey. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(5): 103194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i5/103194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i5.103194

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare autosomal dominant hereditary disorder associated with a pathogenetic mutation in the serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11) gene[1-3]. The syndrome is described on the basis of three principal clinical features, namely, mucocutaneous pigmentation of the lips and extremities[4], the presence of multiple hamartomatous polyps in the digestive tract, particularly in the small intestine, and an elevated risk of malignant tumors[5]. Most clinicians and patients have restricted comprehension of this rare disease until they encounter severe complications such as enteroenteric intussusception resulting from polyps in PJS. In such cases, surgery may be employed as salvage therapy[6,7].

The use of balloon-assisted enteroscopy (BAE) enables the removal of small intestinal polyps, which may have the beneficial effect of preventing complications such as enteroenteric intussusception in PJS (EI-PJS)[8-11]. Furthermore, our previous study demonstrated that BAE can effectively manage select cases of EI-PJS, thereby reducing the need for surgical procedures[12]. However, the BAE procedure is invasive and requires general anesthetic support, with an inherent risk of complications[13]. Therefore, it is essential to weigh the risks of preventive intervention against the natural surgical risk of PJS. Moreover, the identification of the natural surgical risk associated with polyps in PJS and its age distribution can facilitate the development of more cost-effective recommendations for non-invasive surveillance.

Currently, most guidelines' recommendations for polyp screening in PJS are based on expert opinion[14], and data on the natural surgical risks of polyps in PJS are limited to a handful of small studies[6,15] due to its very low incidence of about 1 in 50000-200000 live births. Consequently, we initiated a web-based survey to analyze the natural surgical risks and age distribution of Chinese individuals with PJS.

The study was approved by the Air Force Medical Centre Ethics Committee (2024-09-PJ01). A web-based open survey was launched to collect information from Chinese individuals suspected of having PJS. The survey questionnaire was created via the Tencent platform (https://wj.qq.com) and was developed by our team, drawing on our expertise in managing PJS. At the beginning of the questionnaire, a clear statement was made about the purpose of the web-based survey. The respondents were given the option to either agree to complete the questionnaire and provide truthful information or decline to complete the questionnaire. Only if the first option was chosen could the individual proceed with the subsequent questions. Moreover, patients under the age of 14 years were required to be assisted by a legal guardian during the completion of the questionnaire. Prior to the distribution of the questionnaire, a preliminary survey was conducted with 15 patients diagnosed with PJS who had previously received treatment at our institution. The feedback obtained from this survey was utilized to refine the questionnaire and mitigate the risk of misinterpretation. The questionnaire included a variety of details, including sex, date of birth, place of birth, household registry, family history of PJS, details of mucocutaneous pigmentation, details of the first clinical visit, details of surgical treatment, details of enteroscopic polypectomy, etc. Dense pigmentation was defined as having more than 30 patches on the lips, or it was defined as sparse.

The survey was distributed through a quick response code method, which was shared through the WeChat and QQ instant messaging platforms, specifically with the PJS groups. These groups were managed by volunteers, one of whom was a patient with PJS treated at our center. These groups involve more than 1500 individuals, most of whom have been diagnosed with PJS in medical institutions in China, and some of whom have been suspected of having PJS because they have similar symptoms or a family history of PJS. The collected data during the survey would undergo a process of verification by physicians specializing in the management of PJS. This process was disclosed during the survey. The participants who completed the questionnaire truthfully and completely within the specified time were rewarded with CNY 9 (approximately USD 1.25) as an incentive to increase the response rate.

The data were automatically collected via the Tencent platform. Only questionnaires that had been fully completed in all mandatory fields were included in the subsequent analyses. Questionnaires completed in less than 60 seconds were excluded from the study, as this time frame is insufficient for respondents to read the entire content with sufficient care. In addition, questionnaires that yielded results that did not meet the World Health Organization (WHO) clinical diagnostic criteria for PJS[2] were excluded. Third, patients who had undergone surgery for malignant tumors were also excluded, as this complication will be investigated in further detail in a subsequent study.

The data were analyzed and visualized using R Studio (R4.4.1) or Microsoft Office (Home and Student 2019). The data were analyzed via descriptive statistical methods. The cumulative incidence of surgery was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was employed to ascertain whether there were any statistically significant differences in surgical risk based on sex, family history, pigmentation, or household register. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 500 responses were received from 1129 unique visitors, as determined by IP addresses. Among the total number of respondents, 499 consented to participate in the study and completed the questionnaire. This represented a response rate of 44.20% and completion rate of 100%. However, 57 participants were excluded from the final analysis for the following reasons: 4 participants completed the questionnaire in less than 60 seconds, 16 had undergone surgery for cancer, and 37 did not meet the WHO clinical diagnostic criteria for PJS. A total of 442 participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the final analysis. The median completion time for the questionnaire was 428.5 (277, 760) seconds. The birthplace of the participants covered 28 provinces, autonomous regions, or municipalities in China.

Among the 442 patients, 203 (45.93%) were female, and 239 (54.07%) were male, with an average age of 28.12 ± 11.20 years. There were 186 (42.08%) with the urban register and 256 (57.92%) with the rural register. A total of 164 (37.10%) patients had a positive family history of PJS, whereas 278 (62.90%) were sporadic cases. The majority of patients (n = 435, 98.42%) exhibited mucocutaneous pigmentation, and this symptom presented at a median age of 2 (1, 4) years. Ad

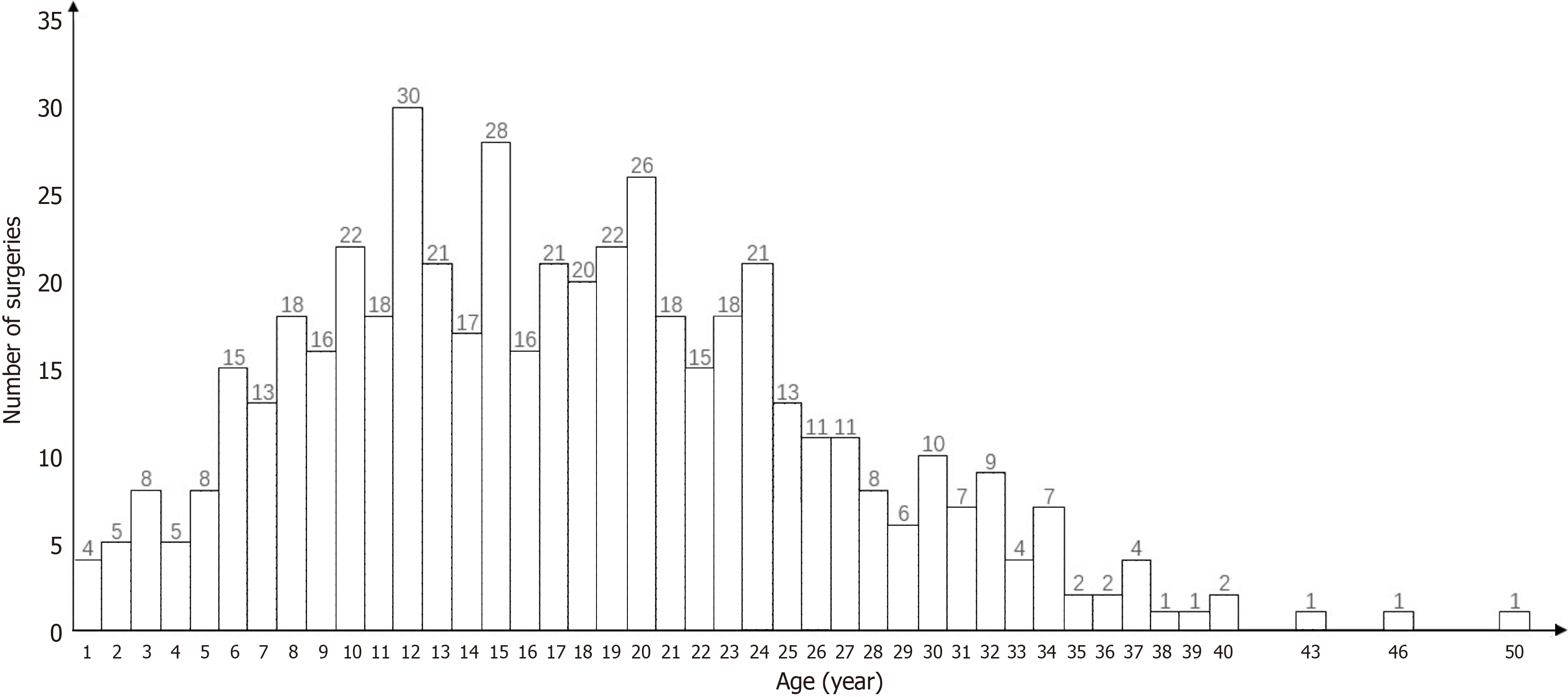

Among the 442 patients with PJS, 301 (68.10%) had undergone 506 surgical procedures prior to the first enteroscopic intervention or the survey deadline. Among the surgical procedures performed, 480 (94.86%) were traditional open surgeries, whereas 26 (5.14%) were laparoscopic procedures. Moreover, 365 (72.13%) patients underwent bowel resection, whereas 141 (27.87%) were limited to polypectomy. The median age at which all procedures were performed was 17 (11-23) years. Specifically, 30 (5.93%) surgical procedures were performed in patients aged 1-5 years, 388 (76.68%) in patients aged 6-25 years, 75 (7.11%) in patients aged 26-35 years, and 13 (2.57%) in patients aged 36 years and older (Figure 1).

Among the 301 patients who underwent surgical procedures, 160 had one procedure, 94 had two procedures, 33 had three procedures, 12 had four procedures, one had five procedures, and one had six procedures. The reasons for the first surgical procedures were intussusception (n = 245, 81.40%, including 54 with concurrent intestinal obstruction and 41 with concurrent necrosis), obstruction (n = 42, 13.95%, intestinal obstruction caused by huge polyps), and gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 14, 4.65%). The average age at each procedure was 15.4 ± 7.71 years for the first, 19.8 ± 8.15 years for the second, 21.6 ± 9.64 years for the third, 23.6 ± 11.2 years for the fourth, 29.5 ± 6.36 years for the fifth, and 40 years for the sixth (Supplementary Figure 2).

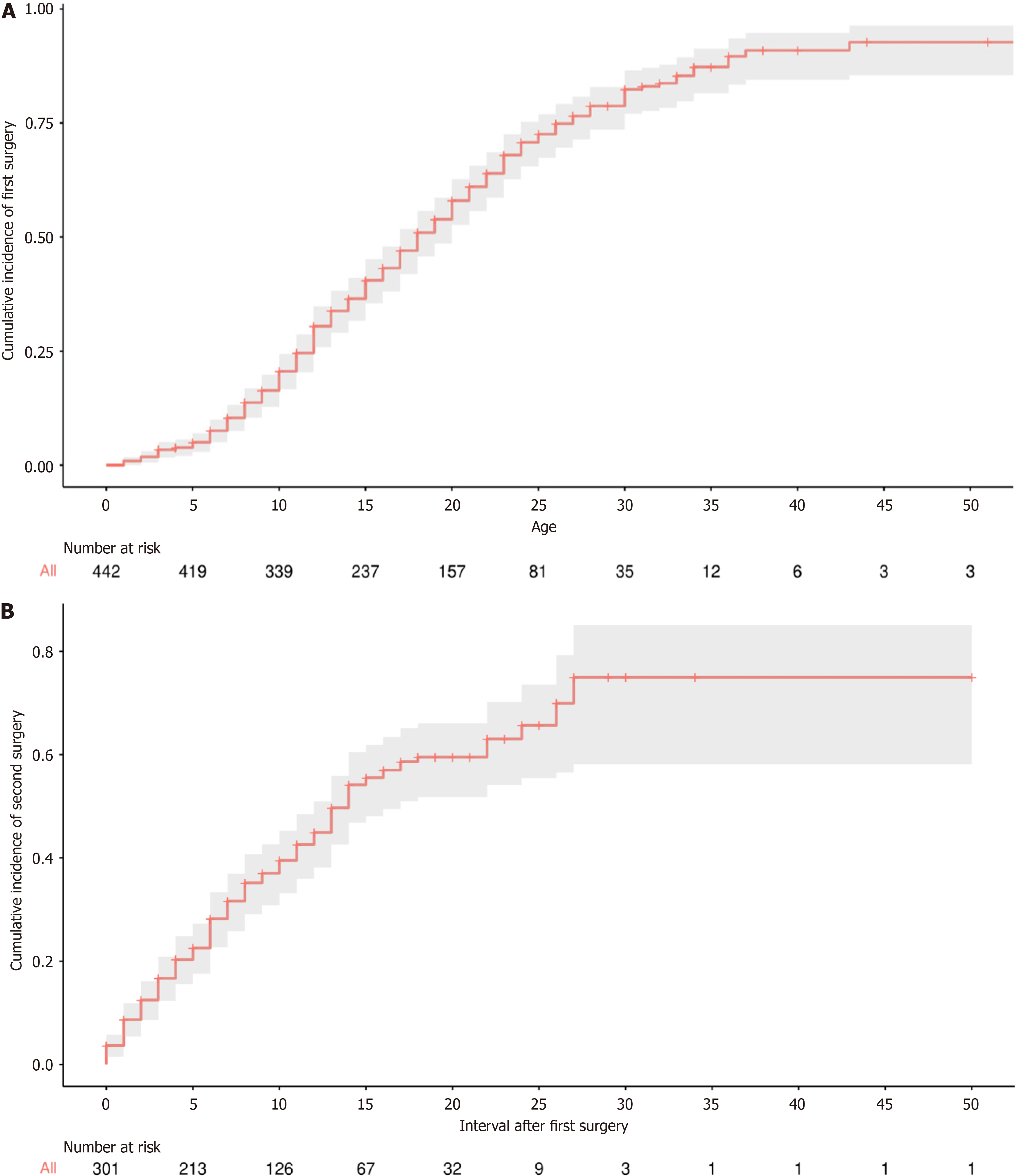

Patients were considered at risk for a first surgical procedure from birth and at risk for a second surgical procedure from the first procedure. The primary endpoint was defined as the first surgical procedure due to PJS or its associated complications, whereas the secondary endpoint was the second procedure. Of the 442 patients, 301 reached the primary endpoint prior to the first enteroscopic preventive intervention or the survey deadline. A further 119 cases were censored due to the administration of the first enteroscopic intervention, whereas 22 cases were censored because they remained free of surgical procedure or enteroscopic intervention until the survey. The natural cumulative incidence of the first surgical procedure was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method (Figure 2A). On the basis of the Kaplan–Meier curves, we estimated the cumulative natural surgical risk for PJS to be 5.0% (95%CI: 2.9%-7.0%) at age 5, 20.6% (95%CI: 16.6%-24.4%) at age 10, 40.5% (95%CI: 35.5%-45.1%) at age 15, 58.0% (95%CI: 52.7%-62.7%) at age 20, 72.6% (95%CI: 67.3%-77.0%) at age 25, and 82.4% (95%CI: 77.0%-86.5%) at age 30. The annual growth rate of the cumulative incidence of surgery was 1.0% per year in the age group 1-5 years, 3.38% per year in the age group 6-25 years, and 1.96% per year in the age group 26-30 years. No significant differences in the risk of first surgery were observed between females and males (P = 0.32), between patients with sparse and dense pigmentation (P = 0.28), or between patients with urban and rural registries (P = 0.4). However, a significant difference in the risk of first surgery was observed between cases with a positive family history of PJS and sporadic cases (P < 0.01; Supplementary Figure 3).

Among the 301 patients who had undergone the first surgical procedure, 141 reached the secondary endpoint before their first enteroscopic prophylactic intervention or the survey deadline, 140 were censored because of their first enteroscopic intervention, and 20 were censored because they remained free of surgery or enteroscopic intervention until the survey deadline. A Kaplan-Meier curve was constructed to estimate the cumulative incidence of a second procedure after the first (Figure 2B). The estimated cumulative incidence was 3.7% (95%CI: 1.5%-5.8%) for a 1-year interval, 12.5% (95%CI: 8.6%-16.2%) for a 3-year interval, 20.3% (95%CI: 15.6%-24.8%) for a 5-year interval, 37.0% (95%CI: 30.8%-42.7%) for a 10-year interval, and 54.2% (95%CI: 46.8%-60.5%) for a 15-year interval. The annual growth rate of the cumulative incidence of a second surgery was 3.61% per year during the initial 15-year interval since the first surgery. No significant differences were observed in the risk of a second surgical procedure after the first procedure between females and males

The results of our real-world study, which was based on a web survey and enrolled a large sample, indicate that surgical treatments inpatients with PJS have some clinical characteristics, including very early age at first surgical treatment, high cumulative incidence, high likelihood of recurrence, the peak age group for surgical treatment is 6-25 years, and the main reason for surgical treatment is intussusception associated with intestinal polyps. These clarified clinical characteristics may be useful in tailoring the current preventive strategy.

In our study, the cumulative incidence of surgery in patients with PJS reached 20.6% at age 10, increasing to 58.0% at age 20 and 82.4% at age 30. The primary indication for surgery was intussusception (81.40%). These results were similar to those of previous reports. In a small sample study, 23 of 34 (68%) patients with PJS underwent laparotomy before they reached 18 years of age[15]. Two other studies reported a high cumulative risk of intussusception in PJS; one reported that it was 50% at the age of 20 and 65% at the age of 30[6], and another reported that it could reach 72.0% at the age of 40 and 89.6% at the age of 50[16], and most intussusceptions were managed by surgery. All of these results suggest that patients with PJS have a high natural surgical risk.

In another retrospective cohort study that included surgery due to polyps and cancers in PJS, the reported surgical rate was 71.2%, and 75.6% of the surgeries were performed before age 35[16]. Despite there being a high risk of cancer in PJS, the cancers are mainly present from the third decade of life with an average age of 42.9 years[17,18]. While, in our study, we included all surgeries caused by noncancer complications, including intussusception, obstruction, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The surgical rate in our study was 68.1%, with a median surgical age of 17 years, and 97.43% of the surgical procedures were performed before the age of 35 years. From our results and other studies, it can be speculated that the natural surgical risk of patients with PJS, particularly in the early stages of life, is attributable primarily to polyp-related complications other than cancers.

Fortunately, current studies have demonstrated the efficacy of BAE-facilitated polypectomy, which enables the safe and effective removal of small intestinal polyps in PJS. This minimally invasive intervention has been shown to have a beneficial effect on the prevention of polyp-related complications in PJS, such as intussusception and obstruction, thereby reducing the need for surgical procedures[8-11,19-21]. Therefore, it is of significant importance to focus on the surgical risk of polyp-related complications in patients with PJS at an early age, implement an appropriate screening strategy, and, if necessary, perform preventive intervention.

The natural surgical risks associated with polyps in PJS and their age distribution are the basis for recommending the appropriate timing of polyp screening and preventive intervention. However, due to the very low incidence of this rare disease, there is still a paucity of data on the age distribution of surgery, and the age at which screening should commence is a matter of contention. The majority of guidelines suggest that individuals with PJS should commence screening for polyps at the age of eight years or earlier[1-3,22-26]. The recommendations were primarily informed by expert opinion[15,27] and a systematic review[28]. However, the authors acknowledged the limited evidence supporting these recommendations in their papers.

In our study, we revealed a marked increase in the frequency of surgical procedures among individuals with PJS since the age of six, with the vast majority of surgeries occurring between the ages of 6 and 25. From the Kaplan-Meier curves for the cumulative incidence of the first surgery, we can estimate that the annual growth rate of the cumulative incidence of surgery was higher for those aged 6-25 years (3.38% per year) than for those aged 1-5 years (1.0% per year) or those aged 26-30 years (1.96% per year). In consideration of the comprehensive age-specific data regarding surgical procedures in PJS, it is recommended that screening should commence at the age of six.

The proposal to commence screening for polyps at an earlier age than previously recommended may prove advantageous for patients who present with polyps at an early age. Our survey demonstrated that patients with this characteristic are not uncommon in this rare disease. We believe that this strategy represents an optimal balance between the prevention of polyp-related complications and the avoidance of over-screening of children. In the event that small intestinal polyps exceeding 10-15 mm in size are detected at the screening stage, invasive preventive intervention with BAE is recommended. Certainly, this intervention strategy is under the majority of current guidelines[1-3,22-26].

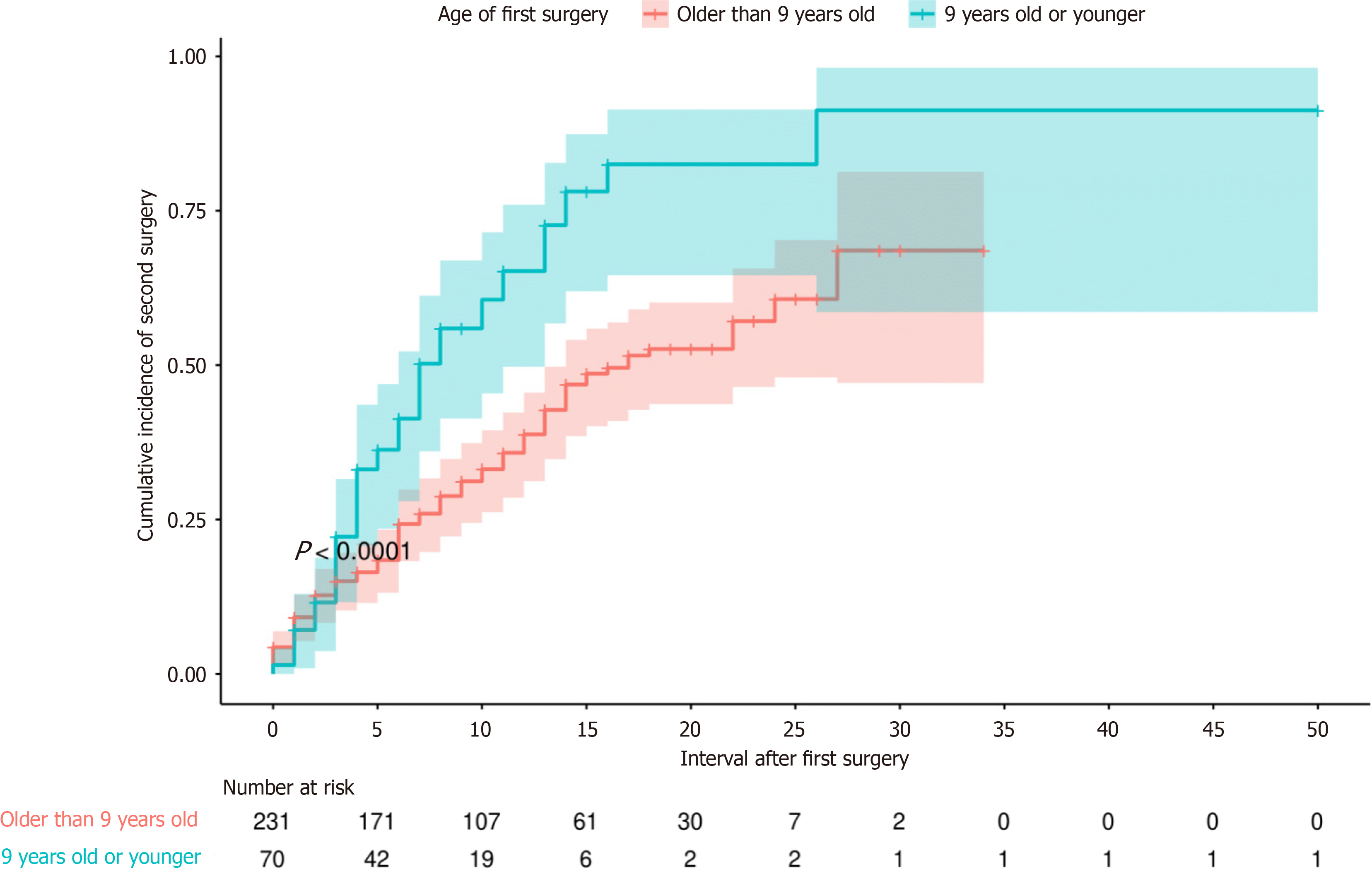

Furthermore, our findings revealed that the cumulative incidence of a second surgical procedure was significantly high in the absence of preventive intervention, reaching 20.3% within 5-year intervals following the first surgery in our study cohort. This figure was lower than that reported in previous research, which reported that 39% of patients underwent a second operation within five years[15]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that previous studies selected patients who underwent their first operation before the age of 18. In our study, patients were grouped according to the age of first surgery, and it was observed that patients who underwent their first surgery at age 9 or younger exhibited a significantly elevated risk in comparison to those who were older, while the stratified analysis according to sex, pigmentation, household register, and family history revealed no significant differences. Considering this evidence, we postulated that patients with PJS may exhibit a distinct polyp burden. It was hypothesized that patients with a more pronounced polyp burden may present at an earlier age and necessitate more frequent surgical interventions.

The presence of different polyp burdens may be associated with specific genotypes, such as truncating variants in STK11[29]. However, data concerning the link between genotype and phenotype are scarce, and further research is needed. Before the clarification of the identified correlations between genotype and severe phenotype, it is recommended that surveillance for polyps in PJS should be conducted on the basis of their clinical presentations. As evidenced by our results, patients who underwent surgery at age 9 or younger should be considered to have an elevated risk of requiring a second surgical procedure and should be subjected to more frequent surveillance.

Currently, there is no unified protocol for the surveillance of polyps, and most guidelines recommend that surveillance should be performed every 1-3 years using non-invasive methods such as video capsule endoscopy or magnetic resonance enterography[1-3,22-26]. In light of our experience in the management of PJS and the results of the present study, it may be necessary to implement individualized follow-up strategies, given the significant interindividual variability in polyp burden and the risk of requiring surgery. Additionally, a flexible strategy of repeated polyp surveillance at intervals of 1-3 years is recommended for patients with PJS. This is because, as demonstrated in our study, patients with PJS remained at elevated risk of requiring a second procedure, particularly within 15-year intervals following their first surgery.

In our study, we also investigated the risk factors for the cumulative incidence of first surgery. Our findings revealed a significant difference between patients with a family history of PJS and sporadic cases. However, the other stratified analyses, according to sex, pigmentation, and household register, did not yield significant results. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study, which indicated that the age at first treatment in patients with a family history of PJS was later than that in sporadic cases[16]. The reason for this phenomenon remains unclear, and further in-depth studies are recommended. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to link pigmentation to surgery caused by polyps in PJS, and the results based on our large sample size revealed that the densities of pigmentation do not affect the cumulative incidence of surgery. The latter is thought to be related to polyp burden, and therefore, evaluating polyp burden based on pigmentation may not be appropriate.

Furthermore, our study focused on the symptom of defecating polyps that has often been disregarded in adult PJS. This symptom may prompt patients to seek medical attention at an early age. In our study, the presence of defecating polyps was identified as a reason for the first clinical visit for PJS in 9.28% of cases, occurring at the earliest age compared with the other symptoms, with a median age of 3 years. This symptom may serve as a potential indicator for the early diagnosis of PJS, facilitating early screening for polyps. It is therefore advised that the symptom of defecating polyps be included as a routine component of the consultation when dealing with patients who are suspected of having PJS.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study, the majority of which are intrinsic to web-based surveys. These limitations include the potential for bias due to the respondents, misunderstanding of the questionnaire, and the introduction of erroneous data. Furthermore, the possibility of spam responses from participants cannot be discounted. However, the response rate achieved by our survey was 44.20%, with participants hailing from more than half of China’s provinces. Additionally, the data were filtered using the WHO's diagnostic criteria and completion time, and underwent a process of verification by physicians specializing in the management of PJS, thus enhancing the representativeness of the dataset. A further limitation of this study is that data on genotype were not collected, as this was beyond the knowledge of the majority of participants. Consequently, it was not possible to link phenotype to genotype. This is an important topic for further research in the field of PJS.

We conducted a web-based survey of Chinese patients with PJS, described the characteristics of surgical treatment caused by polyps, and reported that patients with PJS have a very high natural risk of undergoing surgery, the first surgical treatment can present at a very early age, the frequency of surgery increases sharply after the age of 6 years, and it may occur repeatedly, particularly between the ages of 6 and 25 years. In light of the findings of our study, we propose that early screening, regular surveillance, and preventive interventions if indicated, should commence at six years of age.

We would like to thank everyone who participated in this survey, especially Ms. Mei-Juan He, who is a PJS patient and the founder and administrator of the PJS WeChat groups and QQ groups, and helped us with a lot of promotion and advertising during the survey.

| 1. | Latchford A, Cohen S, Auth M, Scaillon M, Viala J, Daniels R, Talbotec C, Attard T, Durno C, Hyer W. Management of Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: A Position Paper From the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:442-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wagner A, Aretz S, Auranen A, Bruno MJ, Cavestro GM, Crosbie EJ, Goverde A, Jelsig AM, Latchford A, Leerdam MEV, Lepisto A, Puzzono M, Winship I, Zuber V, Möslein G. The Management of Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: European Hereditary Tumour Group (EHTG) Guideline. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Yamamoto H, Sakamoto H, Kumagai H, Abe T, Ishiguro S, Uchida K, Kawasaki Y, Saida Y, Sano Y, Takeuchi Y, Tajika M, Nakajima T, Banno K, Funasaka Y, Hori S, Yamaguchi T, Yoshida T, Ishikawa H, Iwama T, Okazaki Y, Saito Y, Matsuura N, Mutoh M, Tomita N, Akiyama T, Yamamoto T, Ishida H, Nakayama Y. Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome in Children and Adults. Digestion. 2023;104:335-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sato E, Goto T, Honda H. Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, Giardiello FM, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Gross S, Gupta S, Jacobson BC, Patel SG, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Robertson DJ. Diagnosis and Management of Cancer Risk in the Gastrointestinal Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes: Recommendations From the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:2063-2085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Verma A, Kanneganti P, Kumar B, Upadhyaya VD, Mandelia A, Naik PB, Kumar T, Agarwal N. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: management for recurrent intussusceptions. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024;40:148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mohamed Elfeky OW, Panjwani S, Cave D, Wild D, Raines D. Device-assisted enteroscopy in the surveillance of intestinal hamartomas in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Endosc Int Open. 2024;12:E128-E134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Limpias Kamiya KJL, Hosoe N, Takabayashi K, Okuzawa A, Sakurai H, Hayashi Y, Miyanaga R, Sujino T, Ogata H, Kanai T. Feasibility and Safety of Endoscopic Ischemic Polypectomy and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (with Video). Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:252-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cao Z, Jin W, Wu X, Pan W. Endoscopic Therapy of Small Bowel Polyps by Single-Balloon Enteroscopy in Patients with Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:7849055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khurelbaatar T, Sakamoto H, Yano T, Sagara Y, Dashnyam U, Shinozaki S, Sunada K, Lefor AK, Yamamoto H. Endoscopic ischemic polypectomy for small-bowel polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Endoscopy. 2021;53:744-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xiao N, Zhang T, Zhang J, Zhang J, Li H, Ning S. Proposal of a Risk Scoring System to Facilitate the Treatment of Enteroenteric Intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Gut Liver. 2023;17:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Perrod G, Samaha E, Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Berger A, Benosman H, Khater S, Vienne A, Cuenod CA, Zaanan A, Laurent-Puig P, Rahmi G, Cellier C. Small bowel polyp resection using device-assisted enteroscopy in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome: Results of a specialised tertiary care centre. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tacheci I, Kopacova M, Bures J. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37:245-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hinds R, Philp C, Hyer W, Fell JM. Complications of childhood Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: implications for pediatric screening. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:219-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Xu ZX, Jiang LX, Chen YR, Zhang YH, Zhang Z, Yu PF, Dong ZW, Yang HR, Gu GL. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Experience with 566 Chinese cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:1627-1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, Olschwang S, Boardman LA, Gille JJ, Keller JJ, Westerman AM, Scott RJ, Lim W, Trimbath JD, Giardiello FM, Gruber SB, Offerhaus GJ, de Rooij FW, Wilson JH, Hansmann A, Möslein G, Royer-Pokora B, Vogel T, Phillips RK, Spigelman AD, Houlston RS. Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3209-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, Cruz-Correa M, Offerhaus JA. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 961] [Cited by in RCA: 875] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li BR, Sun T, Li J, Zhang YS, Ning SB, Jin XW, Zhu M, Mao GP. Primary experience of small bowel polypectomy with balloon-assisted enteroscopy in young pediatric Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:611-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang YX, Bian J, Zhu HY, Dong YH, Fang AQ, Li ZS, Du YQ. The role of double-balloon enteroscopy in reducing the maximum size of polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: 12-year experience. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Belsha D, Urs A, Attard T, Thomson M. Effectiveness of Double-balloon Enteroscopy-facilitated Polypectomy in Pediatric Patients With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:500-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Boland CR, Idos GE, Durno C, Giardiello FM, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Gross S, Gupta S, Jacobson BC, Patel SG, Shaukat A, Syngal S, Robertson DJ. Diagnosis and management of cancer risk in the gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: recommendations from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1025-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | van Leerdam ME, Roos VH, van Hooft JE, Dekker E, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Latchford A, Neumann H, Pellisé M, Saurin JC, Tanis PJ, Wagner A, Balaguer F, Ricciardiello L. Endoscopic management of polyposis syndromes: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:877-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, Giardiello FM, Hampel HL, Burt RW; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223-62; quiz 263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 957] [Cited by in RCA: 1133] [Article Influence: 103.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pennazio M, Rondonotti E, Despott EJ, Dray X, Keuchel M, Moreels T, Sanders DS, Spada C, Carretero C, Cortegoso Valdivia P, Elli L, Fuccio L, Gonzalez Suarez B, Koulaouzidis A, Kunovsky L, McNamara D, Neumann H, Perez-Cuadrado-Martinez E, Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Piccirelli S, Rosa B, Saurin JC, Sidhu R, Tacheci I, Vlachou E, Triantafyllou K. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy. 2023;55:58-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, Desouza B, Dunlop MG, East JE, Ilyas M, Kaur A, Lalloo F, Latchford A, Rutter MD, Tomlinson I, Thomas HJW, Hill J; Hereditary CRC guidelines eDelphi consensus group. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut. 2020;69:411-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, Moslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bertario L, Blanco I, Bülow S, Burn J, Capella G, Colas C, Friedl W, Møller P, Hes FJ, Järvinen H, Mecklin JP, Nagengast FM, Parc Y, Phillips RK, Hyer W, Ponz de Leon M, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Sampson JR, Stormorken A, Tejpar S, Thomas HJ, Wijnen JT, Clark SK, Hodgson SV. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 516] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Daniell J, Plazzer JP, Perera A, Macrae F. An exploration of genotype-phenotype link between Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and STK11: a review. Fam Cancer. 2018;17:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/