Published online Apr 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.104102

Revised: January 12, 2025

Accepted: February 17, 2025

Published online: April 27, 2025

Processing time: 106 Days and 0.2 Hours

Type III choledochal cysts (CCs) are extremely rare, and they present as di

A young man with a duodenal mass presented with 3-year intermittent abdo

Laboratory tests of cyst aspirates are beneficial for diagnosis, and endoscopic fenestration plus internal drainage works well to mitigate cysts.

Core Tip: In adults with duodenal masses, the possibility of choledochal cysts should be considered. Endoscopic puncture and laboratory examination of aspirates can effectively assist in clarifying the diagnosis. For patients who refuse surgical treatment, endoscopic fenestration plus drainage is a safe, minimally invasive option that provides effective symptomatic relief. Furthermore, long-term periodic follow-up and monitoring utilizing serological tests and imaging are essential.

- Citation: Wang ZM, Su S, Ling-Hu EQ, Chai NL. Type III choledochal cyst confirmed by aspiration and treated with endoscopic fenestration plus internal drainage: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(4): 104102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i4/104102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.104102

Choledochal cysts (CCs) are congenital cystic dilatations of the biliary tree[1]. Most CCs are diagnosed in childhood, with only 25% of CCs identified in adults. The incidence of CCs is 1:100000-150000 in Western populations, and the incidence of CCs is higher in Asian populations, with an incidence of 1:1000[2,3]. The exact cause of CCs remains unknown. Todani classification is the most widely used classification for CCs[4]. Type I CCs are the most common type, followed by type IV CCs[5]. Type III CCs are rare in both the children and adult population but occur more frequently in adults[6]. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for CCs. The present case report emphasizes the comprehensive differential diagnosis of CCs by combining laboratory tests and imaging, and it introduces an option for treatment when the patient refuses surgery.

A 19-year-old Chinese man was referred to gastroenterology at our center with the complaint of intermittent abdominal pain for 3 years, with aggravated pain for 3 days prior to hospitalization.

The patient had intermittent abdominal pain with no apparent cause 3 years prior, which occurred every 1-2 months. The cause of the abdominal pain was unclear because there was no further diagnosis or treatment. The patient’s abdominal pain worsened 3 days prior, mimicking colic symptoms. Laboratory tests revealed a lipase level of 2551.6 U/L (reference range: 13-60 U/L) and an amylase level of 720.1 U/L (reference range: 0-150 U/L). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed pancreatic swelling, suggesting the possibility of pancreatitis. Abdominal ultrasound and CT did not reveal obvious biliary tract structural abnormalities or bile duct stones. The patient was initially diagnosed with acute pancreatitis (AP) at the local hospital, and his symptoms were relieved after early treatment with ulinastatin, octreotide acetate, and omeprazole. The patient was referred to our department for further etiologic diagnosis.

The patient’s blood lipids were normal in previous examinations. The patient denied any other history of disease.

The patient had no history of alcohol consumption. No significant family history was reported.

Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness without rebound tenderness, and no abdominal masses were detected.

Laboratory tests revealed a lipase level of 232.5 U/L (reference range: 13-60 U/L) and an amylase level of 196.5 U/L (reference range: 0-150 U/L). Liver and kidney function tests and tumor marker analysis revealed normal results. Analysis of immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels showed an IgG4 level of 248.0 mg/dL (reference range: 3-201 mg/dL) and an IgG1 level of 1030.0 mg/dL (reference range: 405-1011 mg/dL). Because the IgG4 and IgG1 levels were not significantly elevated, there was little likelihood of autoimmune pancreatitis.

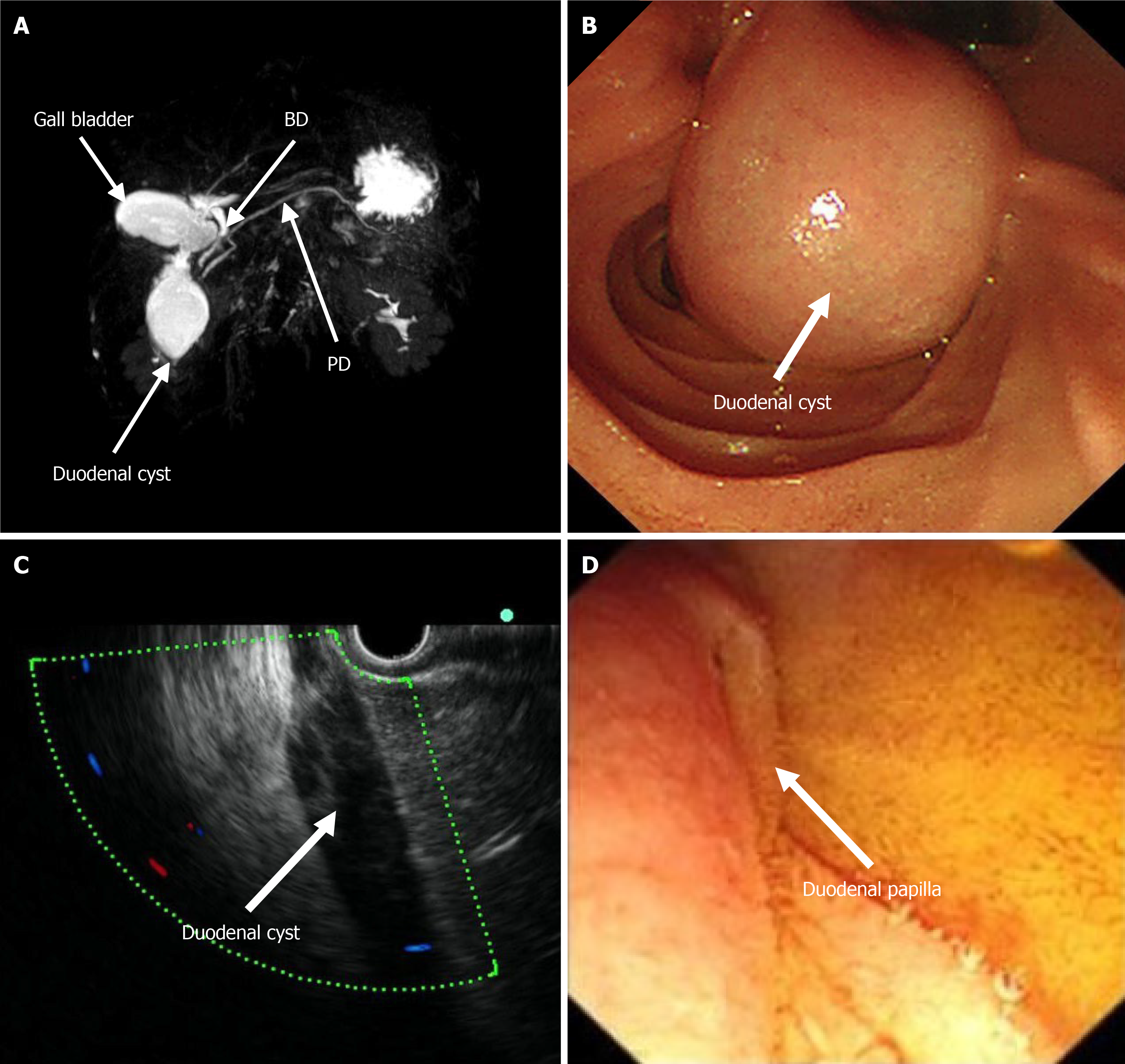

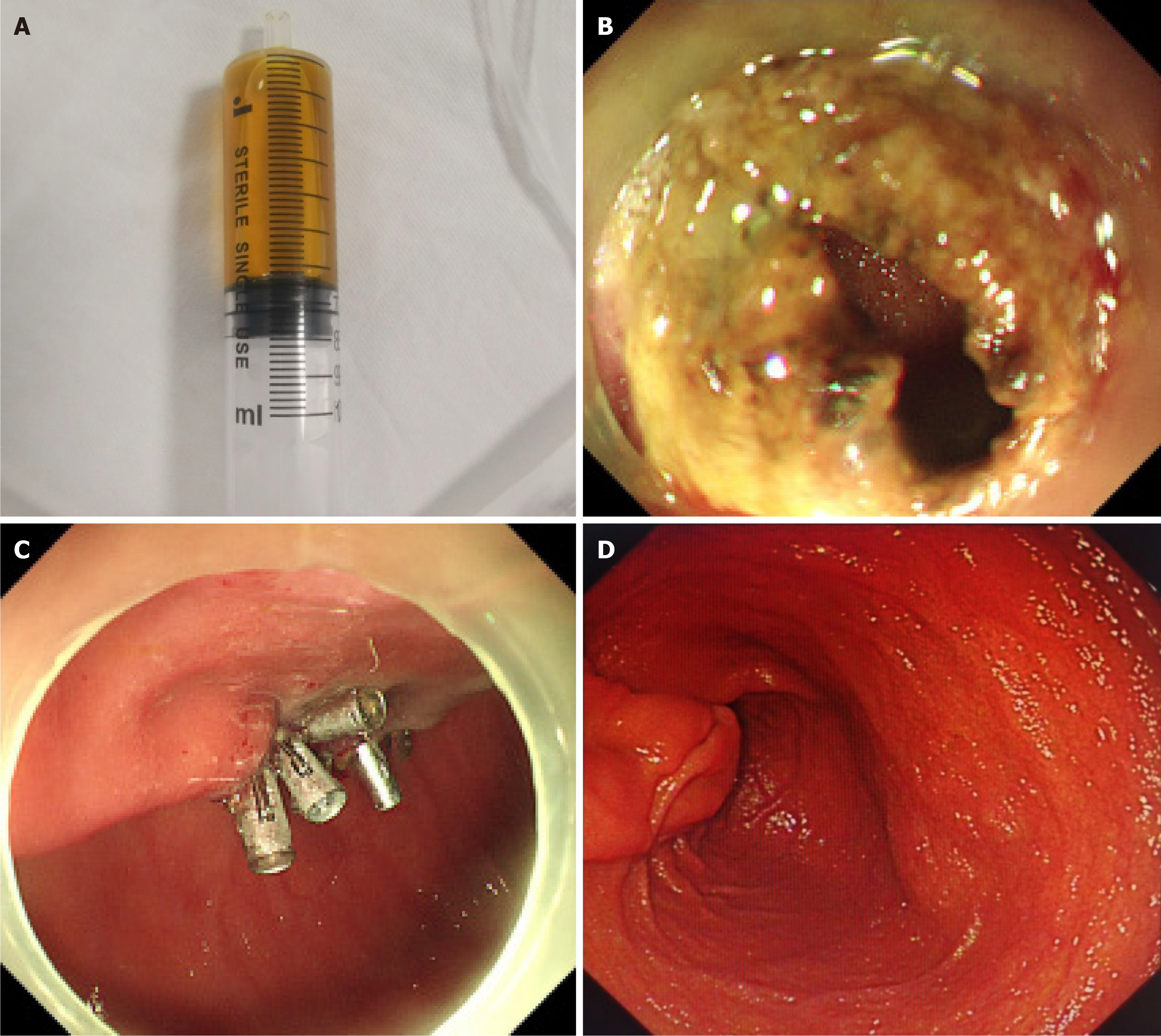

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a duodenal cyst, and no abnormal stenosis or dilatation of the bile duct or pancreatic duct was observed (Figure 1A). Endoscopy revealed a cystic mass in the descending part of the duodenum with a smooth surface and a short diameter of approximately 3 cm (Figure 1B). The lesion had a soft texture. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed a homogeneous hypoecho without blood flow inside the lesion (Figure 1C). After careful evaluation, the duodenal papilla was pressed, and the bile flowed out slowly (Figure 1D), which was speculated to be the cause for his symptoms and AP onset. Subsequently, the lesion was punctured with a submucosal injection needle, and golden clear fluid was aspirated (Figure 2A). Dilute the aspirate 50-fold using a sample diluent of 0.9% sodium chloride. Laboratory tests of the 50-fold diluted aspirate revealed a total bilirubin level of 329.4 μmol/L (reference 0-21 μmol/L), a direct bilirubin level of 243.3 μmol/L (reference 0-21 μmol/L), an amylase level > 59605 U/L (reference 0-150 U/L), and a lipase level > 15000 U/L (reference 13-60 U/L), representing significantly elevated levels. Taken together, these findings confirmed that the lesion was a type III CC.

The lesion was diagnosed as a type III CC.

The patient was fully informed of the treatment and risks involved with the surgery. Given the high risk and trauma of the surgery, the patient refused to undergo surgical treatment. Therefore, fenestration plus internal drainage of the lesion was performed using a DualKnife (Figure 2B). Yellow clear fluid was withdrawn after fenestration, and the inner surface of the cystic cavity was smooth. The lesion was subsequently squeezed repeatedly, and the lesion collapsed after the cystic fluid was extruded. After drainage, the incision was sealed with tissue clips (Figure 2C).

Post-treatment review showed a lipase level of 25.7 U/L (reference range: 13-60 U/L) and an amylase level of 74.9 U/L (reference range: 0-150 U/L). During follow-up, the patient recovered well, and no abdominal pain symptoms or AP recurred. Gastroduodenoscopy revealed no recurrence at three months after treatment (Figure 2D).

CCs are mostly congenital and more common in children. Approximately two-thirds of CCs present at age 10, but this disease can occur at all ages[7]. Although jaundice is common in early childhood, abdominal pain is a major symptom in adolescents and adults[8], as shown in the present case. Notably, such nonspecific symptoms, to some extent, lead to delayed diagnosis. In the present case, the patient presented with intermittent nonspecific abdominal pain for 3 years without other gastrointestinal symptoms, during which the patient was not well examined nor definitively diagnosed. The patient was definitively diagnosed and etiologically treated only when the disease induced AP.

Abdominal ultrasound and CT can be used as preliminary tests to screen for abnormal biliary structures and bile duct stones[9]. However, these tests fail to identify the presence of anomalous pancreaticobiliary junctions[10]. MRI can show the location and morphology of the cyst well. EUS provides a safe and reliable examination method to explore the condition of the bile ducts and to make a differential diagnosis of the cystic nature. Notably, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examination was not prioritized in the present case because the initial abdominal ultrasound and CT missed the identification of CCs. Laboratory tests were performed on aspirates from the cysts, which showed markedly elevated pancreatic enzymes and bilirubin, further clarifying the diagnosis. The supplemental laboratory tests offered new ideas for clinical diagnosis.

Treatment depends on the type of CC. Therapy for types Ι and IV CCs requires complete resection of the choledochus and restoration of bile flow, whereas the strategy for type II CCs includes simple cystectomy or diverticulectomy. Type III CCs can be treated with sphincterotomy or complete resection[11]. When a patient refuses surgical intervention, endoscopic fenestration plus internal drainage is an alternative and cost-effective option, providing a simple, less invasive and reproducible treatment. CCs are usually diagnosed and treated via surgery. However, the present patient was diagnosed with a CC via endoscopic aspiration. CC is often associated with pancreaticobiliary malunion, forming a common channel that typically has cystic fluid. To the best of our knowledge, the present case report is the first to provide laboratory results on the aspirate of a type III CC. Despite the low risk of transformation of type III cysts into malignant tumors, long-term follow-up with biochemical evaluation and abdominal ultrasound is suggested for optimal prognosis.

In summary, the possibility of a CC should be considered for duodenal masses, even in adults. MRI and EUS are helpful for diagnosis, while endoscopic aspiration and laboratory tests can confirm the diagnosis. Although surgical resection is the main treatment for CCs, endoscopic fenestration plus drainage could be an alternative treatment option for patients who refuse surgery.

| 1. | Simmons CL, Harper LK, Patel MC, Katabathina VS, Southard RN, Goncalves L, Tran E, Biyyam DR. Biliary Disorders, Anomalies, and Malignancies in Children. Radiographics. 2024;44:e230109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cazares J, Koga H, Yamataka A. Choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int. 2023;39:209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bhavsar MS, Vora HB, Giriyappa VH. Choledochal cysts : a review of literature. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 934] [Cited by in RCA: 850] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Rastegar N, Anders R, Maithel S, Pawlik TM. Choledochal cysts: presentation, clinical differentiation, and management. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:1167-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soares KC, Kim Y, Spolverato G, Maithel S, Bauer TW, Marques H, Sobral M, Knoblich M, Tran T, Aldrighetti L, Jabbour N, Poultsides GA, Gamblin TC, Pawlik TM. Presentation and Clinical Outcomes of Choledochal Cysts in Children and Adults: A Multi-institutional Analysis. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:577-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sela-Herman S, Scharschmidt BF. Choledochal cyst, a disease for all ages. Lancet. 1996;347:779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Vries JS, de Vries S, Aronson DC, Bosman DK, Rauws EA, Bosma A, Heij HA, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Choledochal cysts: age of presentation, symptoms, and late complications related to Todani's classification. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1568-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Achatsachat P, Intragumheang C, Srisan N, Decharun K, Rajatapiti P, Reukvibunsi S, Kitisin K, Prichayudh S, Pungpapong SU, Nonthasoot B, Sirichindakul P, Vejchapipat P. Surgical aspects of choledochal cyst in children and adults: an experience of 106 cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2024;40:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | De Angelis P, Foschia F, Romeo E, Caldaro T, Rea F, di Abriola GF, Caccamo R, Santi MR, Torroni F, Monti L, Dall'Oglio L. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and management of congenital choledochal cysts: 28 pediatric cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:885-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Soares KC, Ejaz A, Pawlik TM. Management of choledochal cysts. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/