Published online Apr 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.101682

Revised: February 18, 2025

Accepted: March 5, 2025

Published online: April 27, 2025

Processing time: 186 Days and 22.2 Hours

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) during pregnancy is extremely rare. Perforated peptic ulcer (PPU) during pregnancy has high maternal and fetal mortality. Symptoms attributed to pregnancy and other diagnoses make the diagnosis of preoperative PPU during pregnancy and puerperium challenging.

To identify predictive factors for early diagnosis and treatment, and the asso

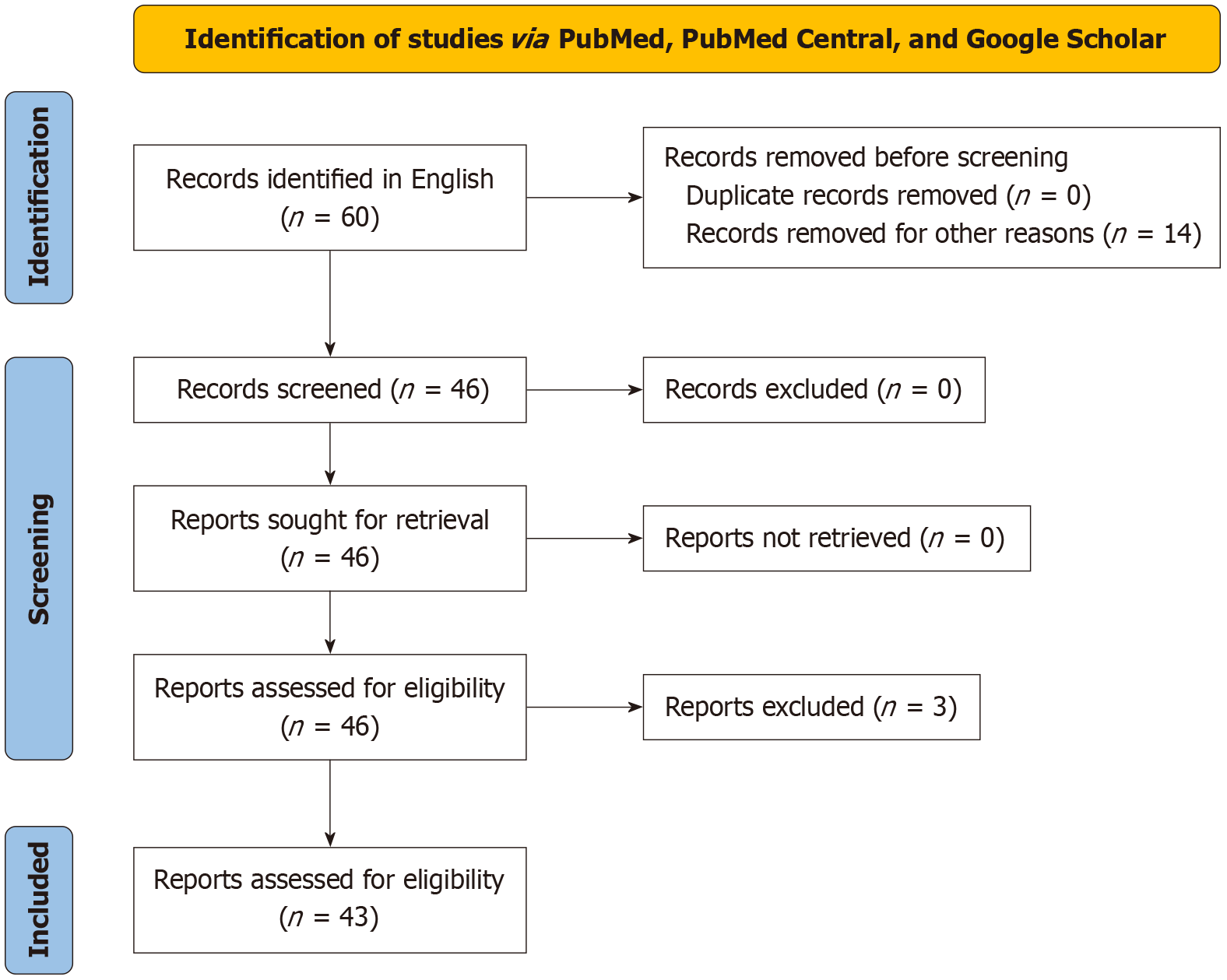

We searched PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar. Articles were analyzed following preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The search items included: ‘ulcer’, ‘PUD’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘puerperium’, ‘postpartum’, ‘gravid’, ‘labor’, ‘perforated ulcer’, ‘stomach ulcer’, ‘duodenal ulcer’, ‘peptic ulcer’. Additional studies were extracted by reviewing reference lists of retrieved studies. We included all available full-text cases and case series. Demographic, clinical, obstetric, diagnostic and treatment parameters, and out

Forty-three cases were collected. The mean maternal age was 30.9 years; 36.6% were multiparous, and 63.4% were nulliparous or primiparous, with multiparas being older than primiparas. Peptic ulcer perforated in 44.2% of postpartum and 55.8% of antepartum patients. Antepartum PPU incidence increased with advancing gestation 2.3% in the first, 7% in the second, and 46.5% in the third trimester. The most common clinical findings were abdominal tenderness (72.1%), rigidity (34.9%), and distension (48.8%). Duodenal ulcer predominated (76.7%). In 79.5%, the time from delivery to surgery or vice versa was > 24 hours. The maternal mortality during the third trimester and postpartum was 10% and 31.6%, respectively. The trimester of presentation did not influence maternal mortality. The fetal mortality was 34.8%, with all deaths in gestational weeks 24-32.

Almost all patients with PPU in pregnancy or puerperium presented during the third trimester or the first 8 days postpartum. Early intervention reduced fetal mortality but without influence on maternal mortality. Maternal mortality did not depend on the use of X-ray imaging, perforation location, delivery type, trimester of presentation, and maternal age. Explorative laparoscopy was never performed during pregnancy, only postpartum.

Core Tip: The correct diagnosis of perforated peptic ulcer in pregnancy was frequently delayed. Almost all patients presented during the third trimester or the first 8 days postpartum. Antepartum incidence increased as the pregnancy advanced. Common symptoms were abdominal tenderness and distension. Early imaging, including plain abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasound, may help in earlier and more accurate diagnosis. Early intervention reduced fetal mortality but without influence on maternal mortality. Maternal mortality did not depend on the use of X-ray imaging, perforation location, delivery type, trimester of presentation, and maternal age. Exploratory laparoscopy was never performed during pregnancy, only postpartum.

- Citation: Augustin G, Krstulović J, Tavra A, Hrgović Z. Perforated peptic ulcer in pregnancy and puerperium: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(4): 101682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i4/101682.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.101682

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a common medical condition caused by hydrochloric acid that breaks down the mucosa and penetrates the submucosa, causing tissue damage. Recurrent symptoms are due to untreated underlying causes [Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) consumption][1]. It includes gastric and duodenal ulcers, and delayed treatment leads to high mortality and morbidity[2]. PUD symptoms are non-specific, delaying the diagnosis. Duodenal ulcers often present with night-time abdominal pain or hunger-associated epigastric pain. In contrast, there is an increase in pain for gastric ulcers, which is not observed in duodenal ulcers.

Currently, a modified Johnson classification of PUD is used. Type I includes ulcers along the body of the stomach, most often along the lesser curve at the incisura angularis, not associated with acid hypersecretion. Type II includes ulcers in the body in combination with duodenal ulcers associated with acid over-secretion. Type III includes an ulcer in the pyloric channel within 3 cm of the pylorus, associated with acid over-secretion. Type IV includes proximal gastroesophageal ulcers. Type V can occur throughout the stomach and is associated with chronic NSAID use. Due to the rarity of the disease and the restricted use of gastroscopy, there are no data on the incidence of these PUD types in pregnancy.

PUD and its complications, such as perforated peptic ulcer (PPU), are extremely rare in pregnancy: 1-6/23000 pregnancies[3,4]. Lower rates of PUD and PPU than in the general population are partly due to healthier habits, such as no smoking, reducing stressful activities, and a balanced diet. At the same time, the primary hormone that promotes pregnancy, progesterone, raises the production of protective gastric mucus. In addition, estrogen reduces gastric acid secretion[5].

PUD diagnosis in pregnancy and puerperium is often delayed because clinical presentation during pregnancy, or puerperium, interferes with common symptoms during pregnancy, such as stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and pregnancy or delivery complications[6].

Also, pregnant women with PUD have a higher incidence of adverse newborn and obstetric outcomes. These include congenital abnormalities, preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption, preeclampsia/eclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine fetal death, or maternal death[7]. All these conditions can mask the underlying cause, delaying the diagnosis.

Case reports and retrospective clinical series are used to evaluate the incidence of PUDs and PPUs in pregnancy, but they are limited due to the lack of data. Also, there are insufficient data on the impact of PPUs in pregnancy and puerperium on maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Our analysis aimed at presenting the most extensive systematic review of cases of PPU in pregnancy and puerperium.

We searched PubMed, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar and analyzed the collected articles, following preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis[8]. The search items included: ‘ulcer’, ‘PUD’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘puerperium’, ‘postpartum’, ‘gravid’, ‘labor’, ‘perforated ulcer’, ‘stomach ulcer’, ‘duodenal ulcer’, ‘peptic ulcer’. Additional studies were extracted by reviewing reference lists of the retrieved studies. We included all available full-text cases and case series. Of the 60 cases identified in our initial search, we excluded 14 due to duplicated, overlapping, or insufficient data, spontaneous stomach rupture or perforation diagnosed at the time of surgery, and patients who were not pregnant or not in the puerperium. After manually reviewing all the cases for eligibility, three additional cases were excluded from the initial search (one with stomach tumor perforation and two abstract-only cases with insufficient information). Finally, 43 cases of PPU in pregnancy and the puerperium met the criteria.

Our goal was to summarize all reported cases of PPU in pregnancy and puerperium and identify predictive factors for early diagnosis and treatment. Our second objective was to identify an association between the diagnosis and maternal/neonatal outcomes. This study is exempt from ethics approval as we collected data from published cases.

Two authors independently reviewed the extracted data from the included articles. Pre-defined criteria were established to ensure the maximum reliability of the collected data.

Obstetric data included maternal age, gestational age, and parity. Clinical/patient characteristic data included gastric risk factors, history of symptoms, and duration of symptoms. Diagnostic data included signs of clinical presentation, clinical presentation, radiology findings, and time of perforation in correlation with delivery. Other parameters collected were differential diagnosis, mother and child outcomes, (season) part of the year, type of delivery, type of surgery performed, time from delivery to operation or vice versa, intraabdominal access, location of ulcer perforation, and preoperative endoscopic diagnostic findings.

All statistical data were processed using JASP Team (2024), JASP (Version 0.18.3). We calculated means and SDs, medians, and interquartile ranges for continuous data. For categorical data, we calculated frequencies and proportions. A t-test was applied to continuous variables, while χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables.

From the 60 cases identified in our initial search (Figure 1), 43 cases of PPU in pregnancy and puerperium fulfilled the criteria. The data from individual case reports are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

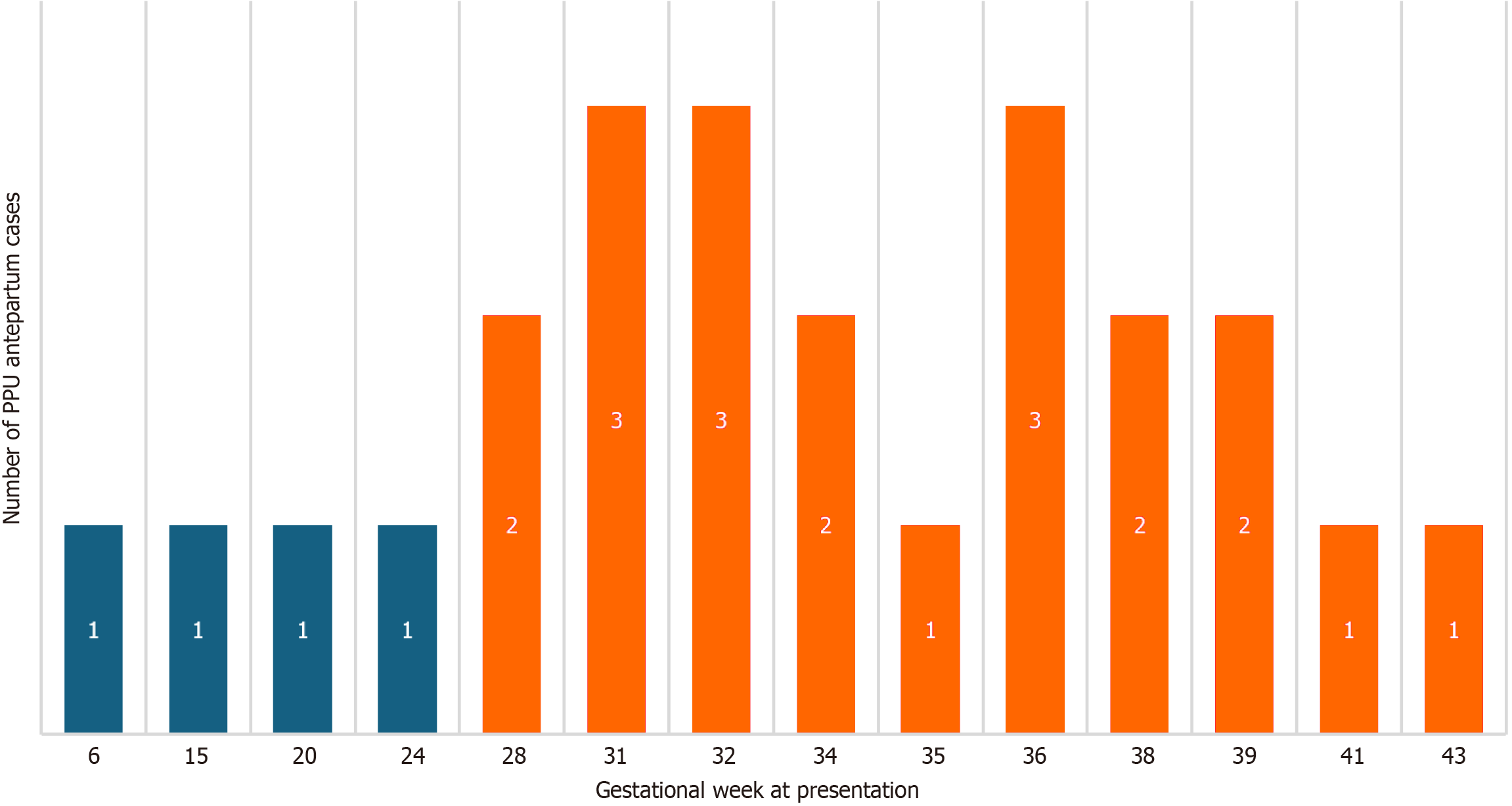

The mean maternal age was 30.9 years (95% confidence interval: 27.9-32.3 years); 36.6% were multiparous, and 63.4% were nulliparous or primiparous. Multiparas were significantly older than primiparas (P < 0.05). Peptic ulcer perforated in 19/43 (44.2%) patients postpartum and 24/43 (55.8%) patients antepartum. Antepartum incidence increased as the pregnancy advanced in these patients, 55.8% were antepartum cases: 2.3% presented in the first, 7% in the second, and 46.5% in the third trimester (Table 1); Postpartum patients presented within the first 8 postpartum days. Parity was not associated with the trimester of presentation. Most antepartum cases (81.8%) occurred in the third trimester (Figure 2). Most women presented with duodenal (76.7%) compared to gastric ulcers (23.3%).

| Baseline information | |

| Mean maternal age, years | 30.9 (95%CI: 27.9-32.3) |

| Multiparous (n = 38) | 15 (39.5) |

| Primiparous (n = 38) | 17 (44.7) |

| Nulliparous (n = 38) | 6 (15.8) |

| Antepartum ulcer perforations (n = 43) | 24 (55.8) |

| Postpartum ulcer perforations (n = 43) | 19 (44.2) |

| First-trimester presentation (n = 43) | 1 (2.3) |

| Second-trimester presentation (n = 43) | 3 (7) |

| Third-trimester presentation (n = 43) | 20 (46.5) |

| Duodenal ulcers (n = 34) | 26 (76.5) |

| Gastric ulcers (n = 34) | 8 (23.5) |

The most common symptoms were abdominal pain 41/43 (95.3%) and vomiting 28/43 (65.1%), with 26/43 (60.5%) presenting with both symptoms (Table 2). Moreover, 37.2% had a history of dyspepsia, peptic ulcer, gastric surgery, or H. pylori infection (Table 3). The most common clinical signs were abdominal tenderness (72.1%), abdominal distension (48.84%), and abdominal rigidity (34.9%) (Table 4). Six patients experienced symptoms lasting < 12 hours, five had symptoms for 12-24 hours, and 22 had symptoms > 24 hours.

| Group | Abdominal pain | Nausea/vomiting | Hematemesis | Diarrhea | Jaundice | Constipation |

| Antepartum (n = 19) | 18 (94.7) | 14 (73.7) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postpartum (n = 24) | 24 (100) | 17 (70.8) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) |

| Maternal medical history | |

| Dyspepsia (n = 43) | 12 (27.9) |

| History of ulcer (n = 43) | 3 (7) |

| Eclampsia/preeclampsia (n = 43) | 6 (14) |

| None (n = 43) | 14 (32.6) |

| Unknown (n = 43) | 8 (18.6) |

| Group | Abdominal tenderness | Abdominal rigidity | Abdominal distension | Absence of peristalsis |

| Antepartum (n = 19) | 17 (89.5) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (21.1) | 5 (26.3) |

| Postpartum (n = 24) | 17 (70.8) | 5 (20.8) | 16 (66.7) | 5 (20.8) |

A plain abdominal X-ray was performed in 11/43 (25.6%), with positive findings in 10/11 (90.9%) as free air under the diaphragm. X-ray imaging did not influence maternal mortality (χ2, P = 0.556). When plain X-ray was not used, fetal mortality was 46.15%, while with plain X-ray use, there was no fetal mortality (sample sizes; n = 13, n = 4). Due to the small sample size, this difference is insignificant (χ2, P = 0.091).

Abdominal ultrasound was performed in 10/43 (23.6%) and was positive in 8/10 (80%), showing free intraperitoneal fluid. The use of ultrasound did not influence maternal mortality (χ2, P = 0.296) or fetal mortality (33.3% vs 36.4%; χ2, P = 0.091; Fischer’s exact test, P = 1.00) (Table 5).

| Diagnostic | |

| Plain abdominal X-ray (n = 43) | 11 (25.6) |

| Positive X-ray findings (n = 11) | 10 (90.9) |

| Abdominal ultrasound (n = 43) | 10 (23.6) |

| Positive findings (n = 10) | 8 (80) |

| Performed vaginal examination (n = 43) | 13 (30.3) |

| Normal (n = 13) | 12 (92.3) |

| Computed tomography (n = 43) | 3 (7) |

In 15 cases, other diagnoses led to the indications for explorative laparotomy. In 2 cases[9,10], explorative laparoscopy was performed in postpartum PPU. Explorative laparoscopy was never performed during pregnancy.

Vaginal examination was performed in 13/43 (30.3%) cases and was normal in 12/13 (92.3%), one patient had prolapsed placental cord.

Suturing of the perforated site was the method of choice (38/43; 88.4%), with partial gastrectomy performed in 2 cases (4.7%). Frequencies for types of surgical operations are listed in Table 6.

| Surgical procedure | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Primary closure | 17 | 39.5 |

| Graham’s patch | 16 | 37.2 |

| Primary closure with omentoplasty | 3 | 7.0 |

| Modified Graham’s patch | 2 | 4.7 |

| Partial gastric resection | 2 | 4.7 |

| No procedure | 3 | 7.0 |

In 31/39 cases, the time from delivery to surgery or vice versa was > 24 hours. Spontaneous vaginal delivery was completed in 20, induced vaginal in 4, and C-section in 16 cases. Outcomes and child and maternal mortality were not related to delivery type, partly due to the small number of cases. The maternal mortality was not related to the trimester of presentation. Maternal age did not influence maternal outcome (30.1 vs 30.1 years; U test, P = 0.988). The gestational week of presentation did not influence fetal mortality (test of log. regression, P = 0.159). Depending on the PPU symptoms duration, maternal mortality was 23.1% for symptoms of < 12 hours (n = 13) and 37.5% for symptoms > 24 hours (n = 16), without statistically significant difference (Fischer’s exact test, P = 0.706). Symptoms lasting 12-24 hours did not result in maternal death. Maternal mortality for duodenal and gastric perforation was 26.9% (7/26) and 25% (2/8), respectively. Maternal mortality did not depend on the perforation location (χ2, P = 0.934).

Fetal mortality was analyzed for patients with symptoms < 12 hours, then with 12-24 hours and > 24 hours. For the first two groups, there were no fetal deaths recorded (8 cases), and fetal mortality for the > 24 hours group was 66.7%, with a statistically significant difference (χ2, P = 0.004; Fischer’s exact test, P = 0.009). The fetal mortality was 34.8%, and all fetal deaths were during gestational weeks 24-32 (Table 7).

| Gestational week at presentation | Number of fetal death outcomes out of total cases by week |

| 15 | 0/1 |

| 20 | 0/1 |

| 24 | 1/1 |

| 28 | 2/2 |

| 31 | 3/3 |

| 32 | 2/3 |

| 34 | 0/2 |

| 35 | 0/1 |

| 36 | 0/3 |

| 38 | 0/2 |

| 39 | 0/2 |

| 41 | 0/1 |

| 43 | 0/1 |

PPUs are uncommon throughout pregnancy and puerperium, leading to delays in diagnosis and surgical intervention[4,11,12]. By systematically analyzing all potential parameters, our study aimed to provide valuable insights into the clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes of PPUs during pregnancy and the puerperium, ultimately guiding mana

Considering the extremely rare occurrence of PPU in pregnancy, studies are scarce. Robin Burkitt documented only three perforated duodenal ulcers in the United Kingdom over 13 (1948-1961) years[13]. In 1962, Lindell and Tera[14] reviewed the literature and reported 14 cases of PPUs during pregnancy, with 100% maternal mortality until their case. In that era, women represented only 10.6% of patients with PPU in the general population[15]. Interestingly, in that era, 50% of women with pregnancy symptoms became asymptomatic during pregnancy[16].

Furthermore, Shirazi et al[17], in 2020, reported their 4 cases of post-cesarean PPU surgically repaired with 50% maternal mortality and collected an additional 8 cases of post-cesarean PPU.

Our study aimed to determine crucial parameters concerning PPU during pregnancy and postpartum. When the whole period of our review is divided into three similar long periods (1939-1970, 1971-2000, and 2000-), only three cases were published in the middle period. Evidently, it occurs in older reproductive women, with a mean age of 31 years. We collected cases from 1939 when first pregnancies began at a younger age. Despite this, PPU is more common in nu

In mice, gastrointestinal transit time is significantly prolonged, and gastric emptying is delayed in the third trimester compared to the postpartum period due to increased progesterone and estradiol levels[20,21]. Increased gastroduodenal mucus levels were found in pregnant rats pretreated with progesterone[22].

The gastroprotective effect of progesterone is maximal in the third trimester when the progesterone level peaks. Exogenous progesterone inhibits the myoelectric and mechanical activity of gastrointestinal smooth muscle. Progesterone relaxes smooth muscle and decreases lower esophageal sphincter pressure[23]. The effect of progesterone on the pyloric sphincter remains unclear. Still, its effect on smooth muscle may affect the prevalence of perforated duodenal ulcers in pregnancy (76.7% vs 23.3%). Also, immunologic tolerance during pregnancy might permit H. pylori to colonize the gastric mucosa without immunologic reaction[4]. In patients with PPU, the prevalence of H. pylori infection is 65%-70%[24]. Prolactin increases the ulcer index and ulcer score in acetic acid-induced chronic gastric ulcers[25]. These factors may significantly affect the third trimester’s high PPU incidence.

The most common symptoms were abdominal pain and vomiting, while clinical examination revealed abdominal tenderness, rigidity, and distension. The vaginal examination was normal. Other studies confirmed these common symptoms, including abrupt and severe abdominal pain, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, pyrexia, dehydration, abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, involuntary guarding, abdominal rigidity, hypoactive bowel sounds, and hypotension[26-28]. In the postpartum period, acute abdominal pain caused by PPU may be mistaken for normal post-delivery discomfort or post-cesarean pain, and patients who receive post-cesarean narcotic analgesics may get relief[11]. A third of the patients had previous dyspepsia or stomach-related conditions, with a similar incidence as in the non-pregnant population.

Most women presented with duodenal ulcers (76.7%). In the general population, males have a higher incidence of PPU, and duodenal ulcers are also more common[29,30].

Standard diagnostic imaging with plain abdominal X-ray or transabdominal ultrasound should be used when PPU is suspected. Although the analyzed period was almost a century, a plain abdominal X-ray was performed in 25.6% and an abdominal ultrasound in 23.6%. Interestingly, both methods are highly accurate (pneumoperitoneum in 90.9% and free intra-abdominal fluid in 80%). Although the presence of ‘free air’ on radiological imaging is strongly symptomatic of a ruptured viscus organ, it may not reveal the cause of pneumoperitoneum[31]. If imaging is not available or inconclusive, a diagnostic laparoscopy should be considered[32]. In our review, explorative laparoscopy was performed only in 2 postpartum cases. Therefore, (diagnostic) laparoscopy is still not a common practice in pregnancy or puerperium.

There are no recommendations for the technique of closure of PPU in pregnancy. In most cases, after primary closure by suturing the perforation site (39.5%), Graham’s patch has been the second most preferred surgical technique (37.2%) (Table 7). For a significant period, these procedures had been the standard method for treating PPUs, particularly when most abdominal surgeries were performed using a midline laparotomy approach. Once again, the protective factors of pregnancy and the reduction or elimination of PUD risk factors may lead to smaller perforations, which can be repaired using the previously mentioned surgical technique. Some of these risk factors are modifiable, such as smoking, NSAID use, drinking, gastritis, and active H. pylori infection[33,34].

Critical issues are maternal and fetal outcomes. The average duration of symptoms before diagnosis or surgical intervention influences outcomes. Maternal mortality is not associated with symptom duration (23.08% and 37.5%), although the trend is lower with shorter duration of symptoms. Maternal mortality does not depend on the use of X-ray imaging, perforation location, delivery type, trimester of presentation, and maternal age.

Contrary to the maternal outcome, fetal mortality increased (0% and 66.7%, symptoms onset < 24 hours and > 24 hours) with longer symptom duration. Therefore, it is of utmost importance for fetal survival to operate on a gravid patient as early as possible, and always within 24 hours. The fetal mortality was 34.8%, and all fetal deaths were during gestational weeks 24-32.

Such patients should be stabilized quickly with electrolyte correction and extensive fluid resuscitation, followed by emergency surgery. Pregnant patients should not receive enteral nourishment and should be given broad-spectrum antibiotics[4]. As in the general population, it is a surgical emergency and delayed surgical treatment leads to short-term mortality of up to 30%[35,36], similar to maternal mortality in this review.

It was challenging to know the exact time the perforation occurred. Many patients had epigastric pain for several days, sometimes even weeks, before PPU developed. The perforation time was estimated when the patients developed severe and sharp pain, much more painful than during previous days. Also, PPU indicators were increased pulse during the disease or the timing of collapse before going to an emergency department. A limitation is the analyzed period of almost a century, although most diagnostic modalities and treatment options for PPU have not changed much.

PPU during pregnancy and puerperium may be mistaken for more common conditions, and the correct diagnosis was frequently delayed. Approximately 1/3 of the women had dyspeptic symptoms before ulcer perforation. Almost all patients presented during the third trimester or the first 8 days postpartum. Antepartum incidence increased as the pregnancy advanced. Common symptoms were abdominal tenderness and distension. Early and mandatory imaging, including plain abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasound, may help in earlier and more accurate diagnosis. Early intervention reduces fetal mortality but not maternal mortality. Maternal mortality did not depend on the use of X-ray imaging, perforation location, delivery type, trimester of presentation, and maternal age. Explorative laparoscopy was never performed during pregnancy, only postnatally.

| 1. | Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374:1449-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 544] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Essilfie P, Hussain M, Bolaji I. Perforated duodenal ulcer in pregnancy-a rare cause of acute abdominal pain in pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:263016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cappell MS. Gastric and duodenal ulcers during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:263-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dumitru A, Gica C, Demetrian M, Botezatu R, Peltecu G, Gica N, Ciobanu A, Panaitescu A. Peptic ulcer disease during pregnancy. Ro Med J. 2022;69:59-62. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Gebremariam T, Amdeslasie F, Berhe Y. Perforated duodenal ulcer in the third trimester of pregnancy. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2015;3:164. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rosen C, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Mishkin DS, Abenhaim HA. Pregnancy outcomes among women with peptic ulcer disease. J Perinat Med. 2020;48:209-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51401] [Article Influence: 10280.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Levin G, Zigron R, Stern S, Gil M, Rottenstreich A. A rare case of post cesarean duodenal perforation diagnosed by laparoscopy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;222:193-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jain A, Azzolini A, Kipnis S. A unique presentation of perforated duodenal ulcer in a postpartum woman: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Munro A, Jones PF. Abdominal surgical emergencies in the puerperium. Br Med J. 1975;4:691-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jones PF, McEwan AB, Bernard RM. Haemorrhage and perforation complicating peptic ulcer in pregnancy. Lancet. 1969;2:350-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Burkitt R. Perforated peptic ulcer in late pregnancy. Br Med J. 1961;2:938-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lindell A, Tera H. Perforated gastroduodenal ulcer in late pregnancy, operated upon with survival of both mother and child. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1962;69:493-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | NORBERG PB. Results of the surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcer: a clinical and roentgenological study. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1959;Suppl 249:1-128. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Augustin G. Acute Abdomen During Pregnancy. 2023. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Shirazi M, Zaban MT, Gummadi S, Ghaemi M. Peptic ulcer perforation after cesarean section; case series and literature review. BMC Surg. 2020;20:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jidha TD, Umer KM, Beressa G, Tolossa T. Perforated duodenal ulcer in the third trimester of pregnancy, with survival of both the mother and neonate, in Ethiopia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goel B, Rani J, Huria A, Gupta P, Dalal U. Perforated duodenal ulcer -a rare cause of acute abdomen in pregnancy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:OD03-OD04. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Coşkun T, Sevinç A, Tevetoğlu I, Alican I, Kurtel H, Yeğen BC. Delayed gastric emptying in conscious male rats following chronic estrogen and progesterone treatment. Res Exp Med (Berl). 1995;195:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Baron TH, Ramirez B, Richter JE. Gastrointestinal motility disorders during pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:366-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Montoneri C, Drago F. Effects of pregnancy in rats on cysteamine-induced peptic ulcers: role of progesterone. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2572-2575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Coquoz A, Regli D, Stute P. Impact of progesterone on the gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive literature review. Climacteric. 2022;25:337-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Thirupathaiah K, Jayapal L, Amaranathan A, Vijayakumar C, Goneppanavar M, Nelamangala Ramakrishnaiah VP. The Association Between Helicobacter Pylori and Perforated Gastroduodenal Ulcer. Cureus. 2020;12:e7406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Asad M, Shewade DG, Koumaravelou K, Abraham BK, Vasu S, Ramaswamy S. Effect of centrally administered prolactin on gastric and duodenal ulcers in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2001;15:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chung KT, Shelat VG. Perforated peptic ulcer - an update. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;9:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 27. | Tew WL, Holliday RL, Phibbs G. Perforated duodenal ulcer in pregnancy with double survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:1151-1152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Winchester DP, Bancroft BR. Perforated peptic ulcer in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;94:280-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sengupta TK, Prakash G, Ray S, Kar M. Surgical Management of Peptic Perforation in a Tertiary Care Center: A Retrospective Study. Niger Med J. 2020;61:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Malik M, Magsi AM, Parveen S, Khan MI, Iqbal M. Duodenal ulcer perforation and its consequences. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023;73:1506-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Thorsen K, Glomsaker TB, von Meer A, Søreide K, Søreide JA. Trends in diagnosis and surgical management of patients with perforated peptic ulcer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1329-1335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cheng HT, Wang YC, Lo HC, Su LT, Soh KS, Tzeng CW, Wu SC, Sung FC, Hsieh CH. Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy in pregnancy: a population-based analysis of maternal outcome. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1394-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Borum ML. Gastrointestinal diseases in women. Med Clin North Am. 1998;82:21-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kurata JH, Nogawa AN. Meta-analysis of risk factors for peptic ulcer. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori, and smoking. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Møller MH, Adamsen S, Thomsen RW, Møller AM; Peptic Ulcer Perforation (PULP) trial group. Multicentre trial of a perioperative protocol to reduce mortality in patients with peptic ulcer perforation. Br J Surg. 2011;98:802-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James P, Watson D, Hinds C, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care. 2006;10:R81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/