Published online Apr 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.100476

Revised: January 13, 2025

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: April 27, 2025

Processing time: 223 Days and 6.6 Hours

Colon cancer is a significant health issue in China, with high incidence and mortality rates. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment, with the introduction of complete mesocolic excision in 2009 improving precision and outcomes. Laparoscopic techniques, including laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy (LARH) and total laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (TLRH), have further advanced colon cancer treatment by reducing trauma, blood loss, and recovery time. While TLRH offers additional benefits such as faster recovery and fewer complications, its adoption has been limited by longer operative times and technical challenges.

To compare the short-term outcomes of TLRH and LARH for the treatment of right -sided colon cancer and explore the advantages and feasibility of TLRH.

Clinical data from 109 right-sided colon cancer patients admitted between January 2019 and May 2021 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were divided into an observation group (TLRH, n = 50) and a control group (LARH, n = 59). Study variables were operation time, intraoperative bleeding volume, postoperative hospital stays, length of surgical specimen, number of lymph nodes dissected, and postoperative inflammatory factor levels of the two groups of patients. The postoperative complications were analyzed and compared, and survival, recurrence, and remote metastasis rates of the two groups were compared during a 2-year follow-up period.

The TLRH group showed the advantages of reduced intraoperative bleeding, shorter hospital stays, and quicker recovery. Lymph node dissection outcomes were comparable, and postoperative inflammatory markers were lower in the TLRH group. Complication rates were similar. Short-term follow-up (2 years) revealed no significant differences in recurrence, metastasis, or survival rates.

Compared to LARH, TLRH offers significant advantages in terms of reducing surgical trauma, lowering postoperative inflammatory factor levels, and mitigating the impact on intestinal function. This approach contributes to a shorter hospital stay and promotes postoperative recovery in patients. The study suggests that TLRH may offer favorable outcomes for colorectal cancer patients.

Core Tip: This retrospective study compared the outcomes of total laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (TLRH) and laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy in right-sided colon cancer patients. TLRH demonstrated the advantages of reduced intraoperative bleeding, shorter hospital stays, and lower postoperative inflammation, while maintaining similar outcomes in lymph node dissection and complication rate. Additionally, no significant differences were observed in survival, recurrence, or metastasis rates over a 2-year follow-up period. The findings suggest that TLRH is a feasible approach that minimizes surgical trauma and enhances postoperative recovery.

- Citation: Du WF, Liang TS, Guo ZF, Li JJ, Yang CG. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted and total laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for right-sided colon cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(4): 100476

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i4/100476.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i4.100476

Colon cancer poses a significant health concern in China, ranking as the third most commonly diagnosed cancer, with an estimated incidence rate of 29.5 per 100000 individuals and a mortality rate placing it fifth in the country. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for colon cancer patients. Traditionally, laparotomy was the standard approach. The introduction of the concept of complete mesocolic excision (CME) in 2009 significantly improved surgical precision[1]. By meticulously minimizing tumor spread and maximizing lymph node clearance, CME aims to enhance patient outcomes, potentially leading to decreased local recurrence rates and improved overall survival[2-4].

The evolution of surgical techniques has introduced laparoscopic approaches, including laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy (LARH) and total laparoscopic right hemicolectomy (TLRH), marking substantial advancements in the field. These approaches offer notable benefits, such as minimized trauma, reduced bleeding, and faster recovery, compared to traditional methods. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic-assisted colon resections were established through multiple randomized trials in the early 2000s, demonstrating advantages such as decreased morbidity, shorter hospital stays, reduced analgesia requirements, and quicker return of bowel function[5-7].

Advancements in patient outcomes continued with the introduction of TLRH, showcasing benefits such as decreased conversion rates, faster return of bowel function, shorter hospital stays, and reduced incisional hernia rates. Despite these advantages, the adoption of TLRH has been slow due to increased operative time and required technical skills[8]. This retrospective analysis assessed patients undergoing either TLRH or LARH. The study aimed to investigate various aspects, including lymph node harvest, surgical duration, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stay, time to the first flatus and defecation, as well as the incidence of complications. Additionally, the research endeavored to compare the short-term outcomes between LARH and TLRH in individuals diagnosed with colon cancer.

This retrospective study was conducted to compare the short-term outcomes of LARH and TLRH. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Liaocheng People’s Hospital Ethics Committee (approval No. 2022173), and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Due to retrospective study design, informed consent was waived by Liaocheng People’s Hospital Ethics Committee.

The inclusion criteria of the present study were as follows: (1) Patients who were diagnosed with right-sided colon cancer via preoperative imaging, colonoscopy biopsy, and postoperative routine histopathology, without distant metastasis; and (2) Patients with complete clinical data and normal functioning of key organs.

Patients were excluded from the present study according to the following criteria: (1) A history of emergency surgeries due to tumors complicated with perforation, bleeding, and obstruction; (2) Distant metastasis observed before the surgery; and (3) A history of previous abdominal surgery or emergency surgery, and patients who underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy. The study enrolled a total of 109 patients between 2019 and 2021. Among these, 50 patients underwent TLRH, constituting the observation group (TLRH), while 59 patients underwent LARH, forming the control group (LARH).

Both surgical methods were completed in accordance with the total mesorectal excision and tumor-free principle. In both groups, all vascular ligations, lymph node dissections, and bowel mobilizations were performed laparoscopically within the abdominal cavity. In the TLRH group, after bowel mobilization and lymph node dissection, the bowel resection and digestive tract reconstruction were completed intracorporeally. In the LARH group, however, bowel resection and digestive tract reconstruction were performed extracorporeally. The specific steps are as follows:

Based on the principles of CME, a central approach was selected. The posterior peritoneum was opened along the surface of the superior mesenteric vein to enter the Toldt’s space. The ileocolic vessels, right colic vessels (if present), right branches of the middle colic vessels, and accessory right colic veins were exposed, ligated, and divided. Corresponding lymphatic tissues at the vascular roots were cleared. Dissection proceeded laterally along the Toldt’s fascia to the right paracolic gutter, while carefully protecting the right gonadal vessels, ureter, and head of the pancreas/duodenum. The terminal ileal mesentery, ascending colonic mesentery, and right transverse mesocolon were fully mobilized. The lateral peritoneum was opened from the ileocecal region along the right paracolic gutter to the hepatic flexure of the colon. The colon was separated from the retroperitoneum in a lateral-to-medial direction until it met the medial dissection plane. At the mid-transverse colon, the gastrocolic ligament was opened. The ligament was divided lateral to the gastroepiploic vessels. Adhesions between the gallbladder and colon were separated, and the hepatocolic ligament was divided. The transverse colon and ascending colon mesentery were freed from the head to the tail until they joined the medial dissection plane. In the TLRH group, the surgery continued intracorporeally. The ileum was divided 15 cm from the ileocecal junction using a Echelon® 60 mm linear stapler with a blue staple cartridge (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, United States). The colon was divided at the mid-right transverse colon using the same stapling device. The terminal ileum, cecum, ascending colon, right transverse colon, and part of the greater omentum were completely resected and placed in a specimen bag. The bowel ends were aligned, and the ileum was sutured and fixed to the distal colon approximately 7 cm from the proximal transected end. The blood supply to both ends was checked, and the tension at the anastomosis site was evaluated. Small incisions (1 cm each) were made on the opposite mesenteric side of the proximal and distal ends of the bowel. The intestinal lumen was disinfected with iodine-soaked gauze. The side-to-side ileocolic anastomosis was performed using a linear stapler. After ensuring no bleeding, the common opening was sutured with 2-0 unidirectional barbed suture to complete the anastomosis. The specimen was removed through the upper midline incision. In the LARH group, a midline longitudinal incision was made in the upper abdomen, and the incision was protected with a protective sheath. The tumor and the connected intestinal segment were brought outside the abdominal wall. The ileum was divided and closed 15 cm from the ileocecal junction, and the colon was divided and closed at the mid-right transverse colon. After removing the right hemicolon, an end-to-side anastomosis was performed between the remaining ileum and colon.

Various parameters were meticulously collected and compared between the two groups. Duration of surgery, resected specimens, the number of lymph nodes dissected, postoperative inflammatory tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and complication rates were recorded in both the observation group and control group. Statistical analyses of recurrence rate and mortality rate during a 2-year follow-up period were conducted, and data were compared between the two groups.

In our pursuit of understanding the nuanced differences between LARH and TLRH, we conducted an in-depth analysis of inflammatory factors. We measured the levels of TNF-α and CRP. These measurements were taken prior to surgery and at postoperative intervals of 1 days and 3 days.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using the t test. Categorical variables are presented as [n (%)] and were compared using the χ2 test or rank-sum test. P values < 0.05 were considered indicative of statistically significant differences. The missing data were addressed through appropriate statistical methods or imputation techniques.

A total of 109 cases were included in this study. After thorough statistical analysis, the study revealed no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, tumor stage, or accompanying diseases between the two groups. The ob

| Basic information | Observation group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 59) | P value | |

| Sex | Male | 23 | 29 | 0.743 |

| Female | 27 | 30 | ||

| Age (years) | < 60 years | 30 | 35 | 0.943 |

| ≥ 60 years | 20 | 24 | ||

| TNM stage | I | 5 | 7 | 0.744 |

| II | 14 | 22 | ||

| III | 31 | 30 | ||

| Accompanying diseases | High blood pressure | 13 | 18 | 0.603 |

| Diabetes | 6 | 8 | 0.808 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 5 | 5 | 0.783 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.69 ± 5.71 | 25.66 ± 6.06 | 0.393 | |

| Operation time (minutes) | 171.1 ± 11.0 | 161.4 ± 9.1 | 0.000 | |

| Intraoperative blood volume (mL) | 154.6 ± 21.9 | 179.8 ± 23.5 | 0.000 | |

| Postoperative hospital stays (days) | 6.43 ± 0.63 | 7.59 ± 2.19 | 0.000 | |

| Postoperative drainage time (days) | 5.18 ± 0.40 | 5.31 ± 0.78 | 0.296 | |

| Time to anal exhaust (days) | 2.49 ± 0.33 | 2.68 ± 0.31 | 0.004 | |

| Length of resected specimens (cm) | 37.8 ± 1.5 | 38.3 ± 1.6 | 0.083 | |

| Average number of lymph nodes dissected | 25.8 ± 2.4 | 25.9 ± 1.6 | 0.691 | |

The duration of surgery in the observation group (TLRH) was longer than that of the control group (LARH), the intraoperative bleeding in the observation group was lower than that of the control group, and hospital stays, postoperative drainage time, and anal exhaust time were shorter in the observation group. Specific comparison values are displayed in Table 1.

Before surgery, there were no statistically significant differences in the levels of TNF-α or CRP between the two groups, indicating comparability at baseline. However, on both the first and third days following surgery, a noticeable shift was observed. In the observation group, the levels of TNF-α and CRP consistently remained lower than those in the control group, and this difference reached statistical significance (Table 2). This temporal pattern suggests a distinct postoperative immunological response in the observation group, reinforcing the potential impact of the surgical intervention on inflammatory markers.

| Group | TNF-α (ng/mL) | CRP (ng/mL) | ||||

| Preoperative | 1 day after operation | 3 days after operation | Preoperative | 1 day after operation | 3 days after operation | |

| Observation group | 8.04 ± 0.71 | 57.47 ± 2.19 | 12.14 ± 0.24 | 17.23 ± 1.36 | 160.40 ± 9.64 | 81.43 ± 4.26 |

| Control group | 10.25 ± 1.15 | 58.60 ± 1.91 | 30.21 ± 1.42 | 16.98 ± 4.36 | 165.18 ± 11.2 | 108.54 ± 3.24 |

| P value | 0.739 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.172 | 0.013 | 0.000 |

The comparison of complications between the two groups revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of incision infection, lung infection, intestinal obstruction, or anastomotic leakage. The observation group demonstrated a lower incision infection rate compared to the control group, which may be attributed to the smaller incision size (Table 3).

| Group | Intestinal obstruction | Anastomotic leakage | Incision infection | Lung infection | Total |

| Observation group (n = 50) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | 6(12) | 12 (24.0) |

| Control group (n = 59) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 7 (11.9) | 8(13.6) | 19 (32.2) |

| P value | 1.000 | 0.884 | 0.255 | 0.808 | 0.344 |

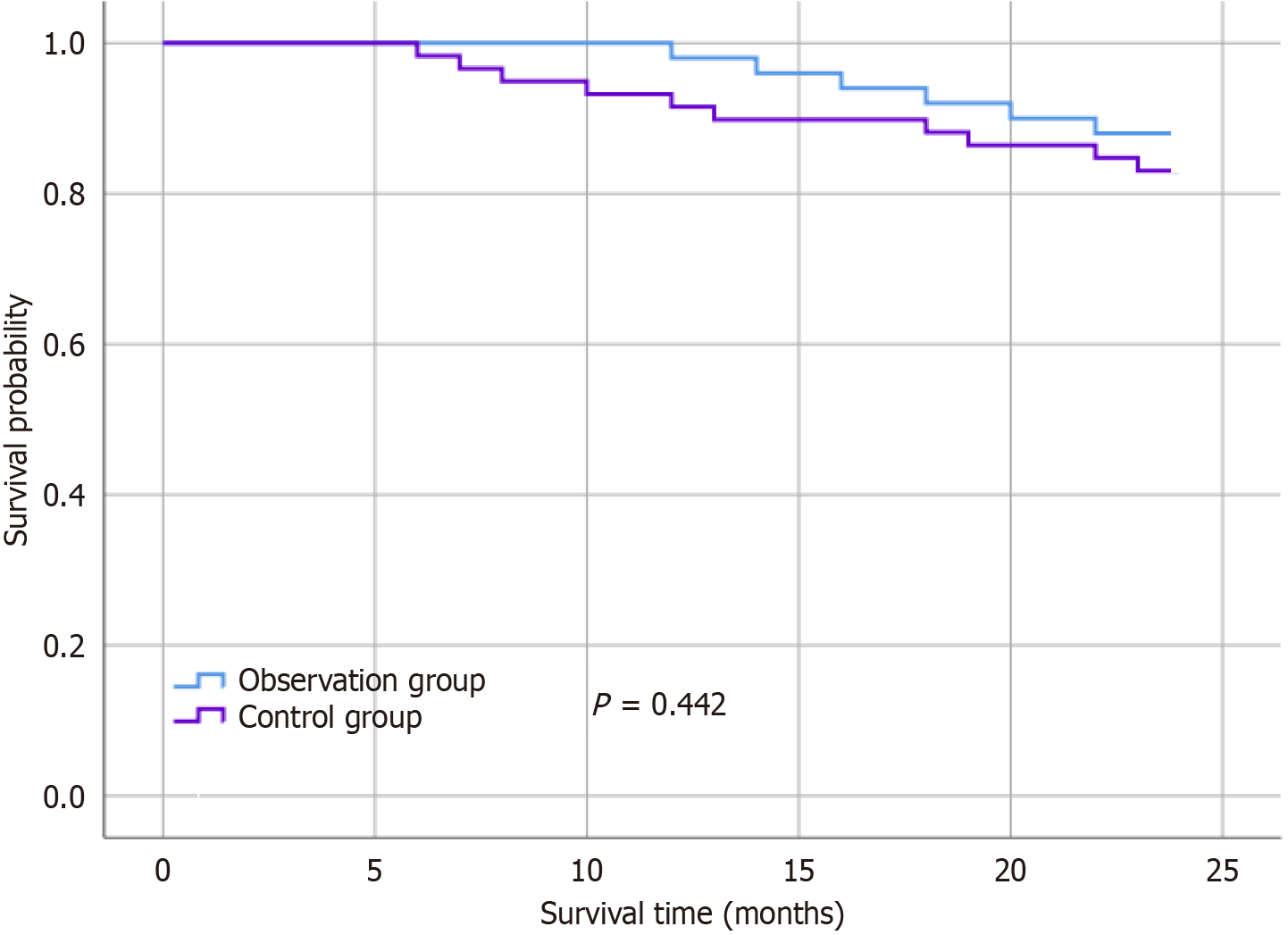

There were no statistically significant differences in the recurrence rate or distant metastasis rate between the observation group and the control group during the 2-year follow-up period (Table 4). Additionally, the survival rate of patients in the observation group showed no significant difference compared to that of the control group (Figure 1).

| Group | Distant metastasis incidence rate at 2 years | Recurrence rate at 2 years | Mortality at 2 years |

| Observation group | 7 (14.0) | 8 (16.0) | 6 (12.0) |

| Control group | 9 (15.3) | 11 (18.6) | 10 (16.9) |

| P value | 0.854 | 0.717 | 0.467 |

The incidence of colon cancer, especially right-sided cases, has been steadily rising in recent years[9]. Surgical resection remains a critical component of treatment, with laparoscopic right hemicolectomy emerging as a preferred minimally invasive option over traditional laparotomy. This technique not only reduces trauma and stress responses but also facilitates faster postoperative recovery. Furthermore, it maintains the structural integrity of the mesocolon and anterior renal fascia, which improves procedural safety and allows for more accurate lymph node dissection aided by enhanced anatomical visualization. Laparoscopic CME has emerged as a low-trauma, minimally invasive alternative for managing right-sided colon cancer[10,11]. Numerous studies, including those by Sheng et al[12] and Huang et al[13], have validated the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic CME. This approach achieves outcomes comparable to open surgery in terms of radical resection and short-term survival. Notable benefits include faster recovery, reduced intraoperative bleeding, shorter hospital stays, and more extensive lymph node dissection[14-16]. Further research has consistently confirmed the feasibility and clinical advantages of laparoscopic CME[17,18]. Evidence from prior studies suggests that CME sig

A study highlights notable improvements in intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stay duration, time to anal exhaust, and the number of lymph nodes dissected in laparoscopic CME for right-sided colon cancer[21]. The visual magnification provided by the laparoscope ensures a clear surgical pathway, a broader field of view, enhanced anatomical identification, reduced blood loss, and prevention of organ injury, all of which contribute to a smoother recovery[22]. Additionally, this approach significantly reduces stress responses and inflammation, as demonstrated by lower levels of inflammatory markers.

The approach to intracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy has undergone significant evolution. Historically, LARH with extracorporeal anastomosis was widely practiced. However, concerns over increased risk and technical challenges drove the exploration of totally laparoscopic techniques. In laparoscopic-assisted procedures, tissue dissection was performed laparoscopically, but anastomosis was completed extracorporeally. This technique, first introduced by Estour in 1993, was later standardized by Senagore and Nelson in 2004, with additional refinements by Estour in 2011[23]. Recent studies have highlighted challenges with extracorporeal anastomosis, such as requiring greater transverse colon mobilization, which can increase the risk of postoperative bleeding. By contrast, TLRH, introduced by Azagra in 1994 and standardized by Ghavami in 2008, performs both tissue dissection and anastomosis intracorporeally. While critics argue that this approach’s increased technical complexity may lead to higher complication rates and longer operative times, advancements in stapling and suturing technology have greatly streamlined intracorporeal procedures, reducing these risks and improving surgical efficiency.

The comparable surgical specimen length and number of dissected lymph nodes between the TLRH and LARH groups underscore the surgical proficiency in achieving oncological objectives. The longer total operation time and anastomosis time in the TLRH group, mitigated by fewer instances of intraoperative bleeding, shorter postoperative hospital stays, and reduced postoperative anal exhaust time, necessitate a nuanced interpretation. The extended operative times may reflect the complexity of TLRH, potentially requiring meticulous surgical techniques. However, the reduced bleeding in TLRH aligns with studies associating minimized blood loss with improved recovery. The shorter postoperative parameters in the TLRH group suggest potential benefits in terms of patient comfort and healthcare resource utilization. Compared to TLRH, LARH often requires more extensive bowel mobilization to extract the intestine through the small incision. In patients with large tumors or significant intra-abdominal fat, this may necessitate enlarging the skin incision, potentially causing excessive traction on the bowel and increasing the risk of colon or mesentery damage. In contrast, intracorporeal anastomosis can mitigate these challenges by minimizing incision size and enhancing the overall minimally invasive nature of the procedure. The corresponding decrease in postoperative levels of TNF-α and CRP in the TLRH group implies a mitigated inflammatory cascade, potentially influencing early recovery and reducing the risk of inflammatory-related complications. While the overall complication rate is comparable, the trend towards a lower incision infection rate in the TLRH group, albeit not statistically significant, underscores the potential benefits of smaller incisions. Minimizing incision-related complications is critical to improving the safety and recovery of patients undergoing minimally invasive procedures. The 2-year follow-up data revealed no significant differences in survival, recurrence, or distant metastasis rate between TLRH and LARH, confirming their oncological equivalence. These findings are consistent with the existing literature, which supports the safety and efficacy of both approaches in delivering comparable oncological outcomes. Clinicians can be reassured that short-term differences in outcomes, such as reduced bleeding and faster recovery with TLRH, do not compromise the long-term integrity of either surgical method. These findings hold practical implications for clinical decision-making. Surgeons may consider the nuanced advantages of TLRH, such as reduced bleeding and shorter hospital stays, particularly in patients where minimizing these factors is crucial. The lack of significant differences in short-term oncological outcomes ensures that both TLRH and LARH remain viable options, allowing for individualized treatment plans tailored to patient-specific considerations.

In conclusion, TLRH demonstrates significant benefits, including reduced surgical trauma, lower postoperative inflammatory factor levels, and less impact on intestinal function compared to LARH. This approach results in a shorter hospital stay and facilitates postoperative recovery. In summary, our study highlights the advantages of TLRH over LARH, showcasing comparable postoperative complication rates. Both procedures exhibit similar short-term outcomes in terms of survival, recurrence, and distant metastasis rates. Considering these findings, TLRH emerges as a preferable option for patients undergoing right-sided colon cancer surgery. These insights contribute to informed clinical decision-making and potential refinements in treatment protocols for individuals with right-sided colon cancer. Our results suggest that TLRH is a safe and feasible approach for treating right-sided colon cancer, emphasizing the need for further research to comprehensively validate these findings.

| 1. | Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:354-64; discussion 364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 990] [Cited by in RCA: 1150] [Article Influence: 67.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brunner M, Weber GF, Wiesmüller F, Weber K, Maak M, Kersting S, Grützmann R, Krautz C. [Laparoscopic Right Hemicolectomy with Complete Mesocolic Excision (CME)]. Zentralbl Chir. 2020;145:17-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan PJ, Quirke P. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:272-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eiholm S, Ovesen H. Total mesocolic excision versus traditional resection in right-sided colon cancer - method and increased lymph node harvest. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57:A4224. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bertelsen CA, Bols B, Ingeholm P, Jansen JE, Neuenschwander AU, Vilandt J. Can the quality of colonic surgery be improved by standardization of surgical technique with complete mesocolic excision? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1123-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gouvas N, Pechlivanides G, Zervakis N, Kafousi M, Xynos E. Complete mesocolic excision in colon cancer surgery: a comparison between open and laparoscopic approach. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1357-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Laurent C, Leblanc F, Wütrich P, Scheffler M, Rullier E. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: long-term oncologic results. Ann Surg. 2009;250:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Magistro C, Lernia SD, Ferrari G, Zullino A, Mazzola M, De Martini P, De Carli S, Forgione A, Bertoglio CL, Pugliese R. Totally laparoscopic versus laparoscopic-assisted right colectomy for colon cancer: is there any advantage in short-term outcomes? A prospective comparative assessment in our center. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2613-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Anania G, Davies RJ, Bagolini F, Vettoretto N, Randolph J, Cirocchi R, Donini A. Right hemicolectomy with complete mesocolic excision is safe, leads to an increased lymph node yield and to increased survival: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2021;25:1099-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim SJ, Ryu GO, Choi BJ, Kim JG, Lee KJ, Lee SC, Oh ST. The short-term outcomes of conventional and single-port laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254:933-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park JS, Choi GS, Jun SH, Hasegawa S, Sakai Y. Laparoscopic versus open intersphincteric resection and coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer: intermediate-term oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg. 2011;254:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sheng QS, Pan Z, Chai J, Cheng XB, Liu FL, Wang JH, Chen WB, Lin JJ. Complete mesocolic excision in right hemicolectomy: comparison between hand-assisted laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2017;92:90-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang JL, Wei HB, Fang JF, Zheng ZH, Chen TF, Wei B, Huang Y, Liu JP. Comparison of laparoscopic versus open complete mesocolic excision for right colon cancer. Int J Surg. 2015;23:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | An MS, Baik H, Oh SH, Park YH, Seo SH, Kim KH, Hong KH, Bae KB. Oncological outcomes of complete versus conventional mesocolic excision in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:E698-E702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ding Z, Wang Z, Huang S, Zhong S, Lin J. Comparison of laparoscopic vs. open surgery for rectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feng B, Sun J, Ling TL, Lu AG, Wang ML, Chen XY, Ma JJ, Li JW, Zang L, Han DP, Zheng MH. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision (CME) with medial access for right-hemi colon cancer: feasibility and technical strategies. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3669-3675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fabozzi M, Cirillo P, Corcione F. Surgical approach to right colon cancer: From open technique to robot. State of art. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:564-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 18. | Ramachandra C, Sugoor P, Karjol U, Arjunan R, Altaf S, Patil V, Kumar H, Beesanna G, Abhishek M. Robotic Complete Mesocolic Excision with Central Vascular Ligation for Right Colon Cancer: Surgical Technique and Short-term Outcomes. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2020;11:674-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, Wilhelmsen M, Kirkegaard-Klitbo A, Tenma JR, Bols B, Ingeholm P, Rasmussen LA, Jepsen LV, Iversen ER, Kristensen B, Gögenur I; Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, Choi HS, Kim DW, Chang HJ, Kim DY, Jung KH, Kim TY, Kang GH, Chie EK, Kim SY, Sohn DK, Kim DH, Kim JS, Lee HS, Kim JH, Oh JH. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mori S, Baba K, Yanagi M, Kita Y, Yanagita S, Uchikado Y, Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Okumura H, Nakajo A, Maemuras K, Ishigami S, Natsugoe S. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with radical lymph node dissection along the surgical trunk for right colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Giani A, Bertoglio CL, Mazzola M, Giusti I, Achilli P, Carnevali P, Origi M, Magistro C, Ferrari G. Mid-term oncological outcomes after complete versus conventional mesocolic excision for right-sided colon cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:6489-6496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Farinella E, Guarino S, Desiderio J, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Slim K. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis during laparoscopic right hemicolectomy - systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/