Published online Mar 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.95704

Revised: October 4, 2024

Accepted: November 4, 2024

Published online: March 27, 2025

Processing time: 313 Days and 21.7 Hours

Gastrointestinal submucosal tumors (SMTs) mostly grew in the lumen, but also some of the lesions were extraluminal, in which the stomach was the most co

To investigate the effect of combined application of the preclosure technique and dental floss traction in gastric wound closure following EFTR.

In this study, the data of 94 patients treated for gastric SMTs at the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Center of the Affiliated Union Hospital of Fujian Medical University from April 2022 to May 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into a preclosure group (54 patients) and a non-preclosure group (40 patients) on the basis of the timing of wound closure with titanium clips after dental floss traction-assisted EFTR. Each patient in the preclosure group had their wounds preclosed with titanium clips after subtotal lesion resection, whereas each patient in the non-preclosure group had their wounds closed with titanium clips after total lesion resection. The lesion size, wound closure time, number of titanium clips used, incidence of postoperative complications, and postoperative hospitalization time were compared between the two groups.

The wound closure time was significantly shorter in the preclosure group than in the non-preclosure group (6.69 ± 2.109 minutes vs 11.65 ± 3.786 minutes, P < 0.001). The number of titanium clips used was significantly lower in the preclosure group (8.93 ± 2.231) than in the non-preclosure group (12.05 ± 4.495) (P < 0.001). There was no sig

Application of the preclosure technique combined with dental floss traction can be used intraoperatively to effectively close the surgical wound in patients undergoing EFTR, reliably preventing the tumor from falling into the peritoneal cavity.

Core Tip: Using the endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) technique to treat gastric submucosal tumors, the use of external dental floss traction with endoscopic therapy can provide a clearer surgical field, thereby reducing surgical difficulty and the risk of intraoperative bleeding. In EFTR, the preocclusion technique combined with dental floss traction can effectively close the defect, effectively prevent the tumor from falling into the abdominal cavity. This approach is undou

- Citation: Zu QQ, You Y, Chen AZ, Wang XR, Zhang SH, Chen FL, Liu M. Combined application of the preclosure technique and traction approach facilitates endoscopic full-thickness resection of gastric submucosal tumors. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(3): 95704

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i3/95704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i3.95704

Gastrointestinal submucosal tumors (SMTs) are protuberant lesions that originate in the muscularis mucosa, submucosa, or muscularis propria (including gastrointestinal leiomyomas, Brunner's gland adenomas, granulosa cell tumors, lipomas, schwannomas, glomus tumors and ectopic pancreatic tissue); some of these lesions are extraluminal[1]. The incidence rates of SMTs in various parts of the digestive tract differ; however, the stomach is the most common site for SMTs in the digestive tract[2]. According to relevant expert guidelines, endoscopic surgical resection of small-diameter gastric SMTs can be considered when endoscopic techniques are available and patients are willing to receive radical treatment[3]. However, for gastric SMTs with a diameter of less than 10 mm, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and the related techniques are too complicated and difficult to perform. In recent years, endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) has been increasingly widely used to treat patients with small-diameter gastric SMTs[4], thereby achieving a complete resection rate of 100% and extremely low complication rates[5]. However, proper closure of the perforation site after EFTR is key to the success of this approach. On this basis, in this study, ‘preclosure’ was investigated. Preclosure is a procedure by which, after dental floss traction-assisted EFTR for a gastric SMT, the wound is first preclosed with titanium clips before lesion excision. In this study, preclosure shortened the wound closure time and reduced the number of titanium clips used.

In this study, the data of 94 patients treated with EFTR for gastric SMTs by a skilled endoscopist at the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Center of the Affiliated Union Hospital of Fujian Medical University from April 2022 to April 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. In this study, to exclude interoperator differences, all operations were performed by the same endoscopist with the same equipment. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with gastric SMTs diagnosed by conventional endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), computed tomography (CT) or other imaging examinations[3]; (2) Patients with gastric SMTs with diameters ≤ 2 cm found to originate from the gastric submucosa or muscularis propria by EUS[6]; (3) Patients who were 32-78 years in age; (4) Patients with single lesions; and (5) Patients with tumor sites restricted to the gastric body, gastric fundus and gastric fundus-body junction. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases; (2) Patients with abnormal coagulation function; (3) Patients with metastasized tumors; (4) Patients exhibiting tumors with a diameter > 2 cm; and (5) Patients who refused endoscopic treatment. The patients were grouped on the basis of the timing of wound closure with titanium clips after dental floss traction-assisted EFTR. Patients in whom the wound was preclosed with titanium clips after subtotal lesion resection before receiving complete wound closure were included in the preclosure group (54 patients), and patients in whom the wound was closed with titanium clips after total lesion resection were included in the non-preclosure group (40 patients). There was no significant difference in sex, age, history of hypertension, history of diabetes mellitus, or history of abdominal surgery between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Union Hospital of Fujian Medical University. All patients completed relevant examinations after admission, were fully informed before surgery, and signed a consent form for endoscopic treatment.

| Group | Sex (patients) | Age (years) (mean ± SD) | Hypertension (cases) | Diabetes mellitus (case) | History of abdominal surgery (case) | |

| Male | Female | |||||

| Preclosure group | 22 | 32 | 57.13 ± 10.37 | 13 | 2 | 14 |

| Non-preclosure group | 16 | 24 | 54.18 ± 8.44 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| χ2/t value | 0.005 | 1.475 | 1.173 | 0.120 | 0.146 | |

| P value | 0.942 | 0.144 | 0.279 | 0.729 | 0.702 | |

The following table provides information regarding the endoscope and related instruments (Table 2).

| Instrument name | Model | Manufacturer |

| Gastroscope host | EPK-i7000 | PENTAX |

| Electronic upper gastrointestinal endoscope | EG29-i103.2 | PENTAX |

| High-frequency electric cutting device | VI200S | ERBE |

| CO2 insufflator | UCR | Olympus |

| IT knife | KD-612 L | Olympus |

| Dual knife | KD-650 L | Olympus |

| Transparent cap | D-201-11804 | Olympus |

| Thermal biopsy forceps | HDBF-2.4-230-S | COOK |

| Injection needle | VIN-23 | COOK |

| Electric snare | AG-5072-242523 | AGS MedTech |

| Clip device | AG-51042-1950-135-16 | AGS MedTech |

| Irrigation pump | MD4-185 | AOHUA |

Preoperative preparation: Antipyretic, analgesic, antiplatelet and anticoagulant drug treatments were discontinued one week before surgery, and a complete blood count and coagulation tests (PLT, FIB, and DD) were performed. The pre-endoscopic preparation was the same as the gastrointestinal preparation for conventional endoscopy. All patients underwent endoscopic surgery under general anesthesia.

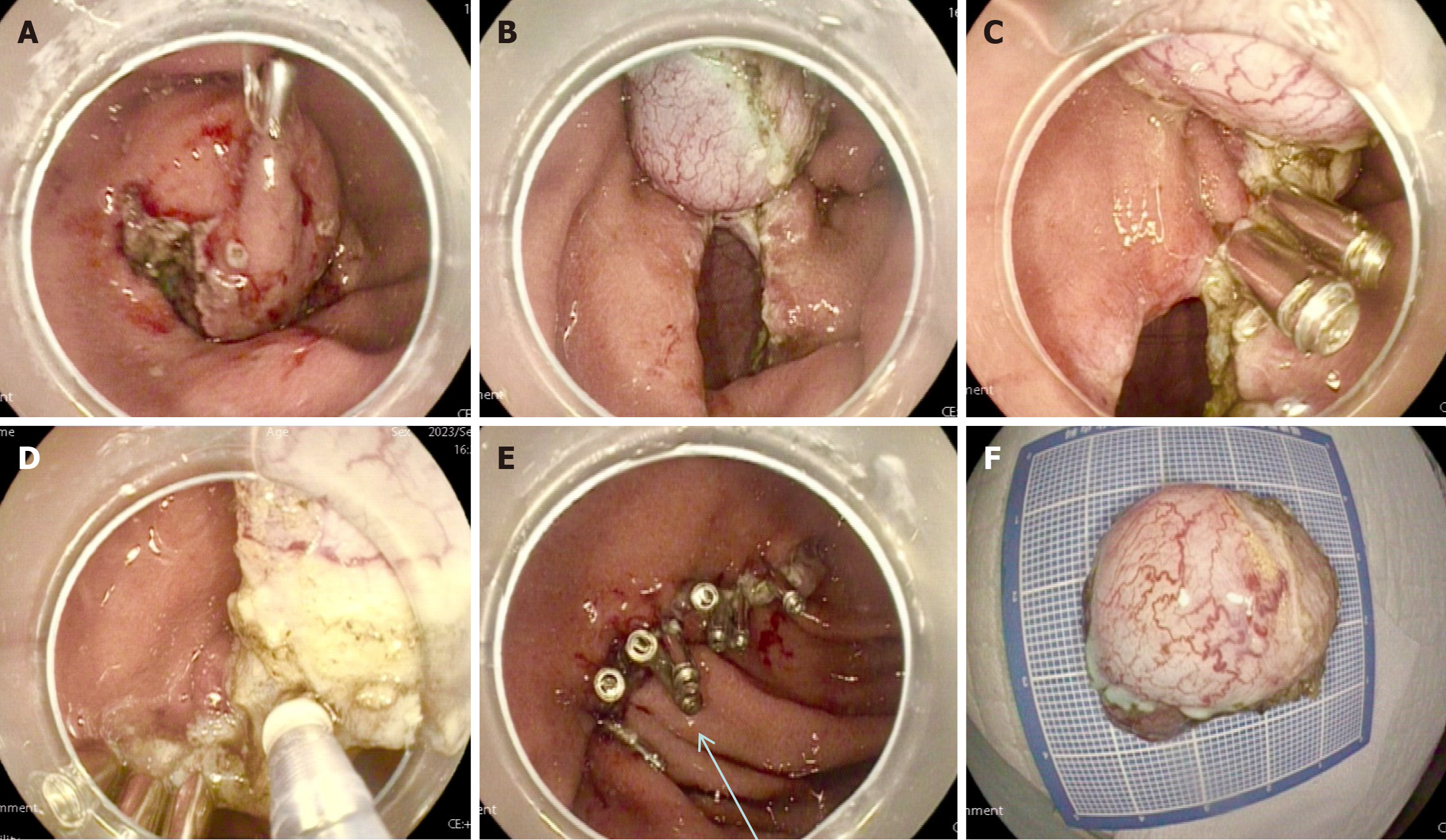

Surgical methods: (1) Marking and injection: The edge of the lesion was marked by electrocoagulation using a dual knife. Submucosal injections were performed outside the marked point on the anal side. Care was taken to limit the amount of material injected to 1 mL; slight elevation of the mucosa at each lesion was sufficient; (2) Incision: The mucosa and submucosa around the tumor were incised with a dual knife in a semicircular manner to expose part of the tumor; (3) Installation of the dental floss traction device: The gastroscope was first withdrawn, and then the clip device was inserted through the forceps channel of the gastroscope. The dental floss was fixed on one arm of the clip device via the double-knot method. After entry of the gastroscope, the clip device with dental floss was clamped at the incisal edge of the lesion, and the lesion was pulled upward by moderate traction using the hemostatic forceps to fully expose the su

Specimen processing: Fresh, completely resected SMT specimens were rinsed and spread out to observe, measure and record the characteristics (size, shape, color, hardness, integrity of the capsule, etc.) of each. The samples were then placed in formaldehyde for pathological examination[1,3].

Postoperative treatment: All patients received oxygen (inhaled) and were monitored by ECG after surgery, and their vital signs were closely monitored. The patients rested in a semirecumbent position. After fasting for 3-4 days after the operation, the patients were assessed for abdominal pain, abdominal distension, hematemesis, and fever. Routine acid suppression, fluid replacement, and nutritional support were provided. If an indwelling gastrointestinal decompression tube was placed, the tube was properly managed.

Observation indicators: The wound closure time, number of titanium clips used during the operation, length of postoperative hospital stay, tumor size, pathological results, and number of postoperative fasting days were recorded for the two groups of patients.

SPSS 27.0 statistical software was used for statistical analyses. Normally or approximately normally distributed data are expressed herein as mean ± SD, and count data are expressed as the rate or composition ratio. Measurement data were compared between the two groups by using the t test or t test, and count data were compared between the two groups via the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

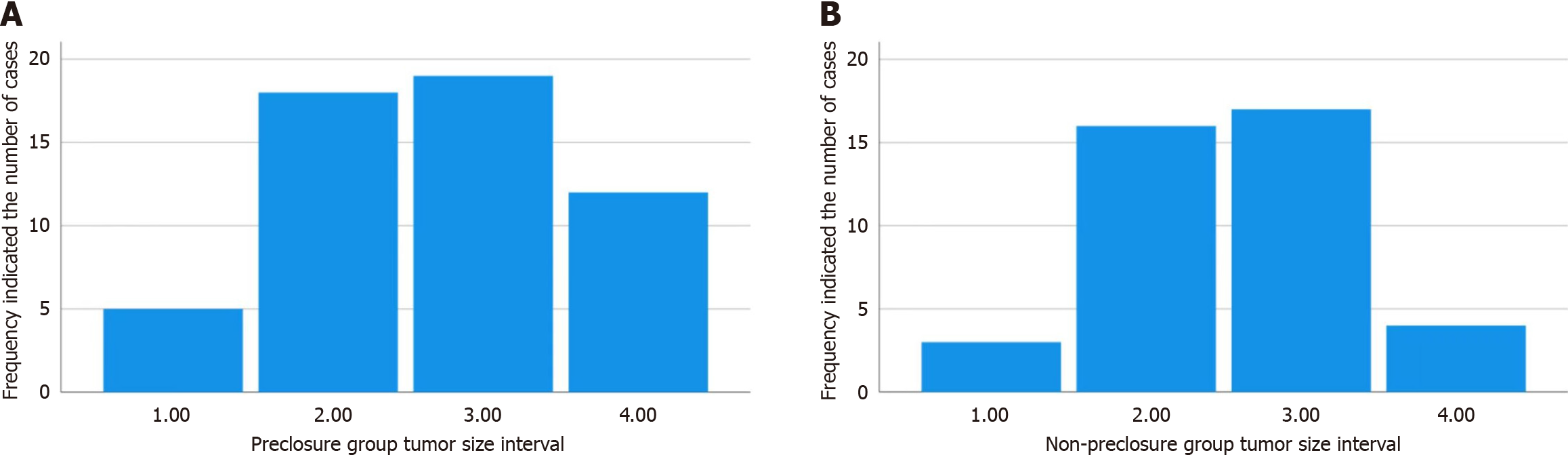

The average size of the tumors in 94 patients diagnosed by EUS and CT was 1.13 cm (0.3-1.9) cm (Figure 2). One tumor was located in the posterior wall of the cardia (1%), 50 tumors were located in the gastric fundus (53.2%), 33 tumors were located in the gastric body (35.1%), 2 tumors were located in the gastric antrum (2.1%), 1 tumor was located in the gastric angle (1%), 6 tumors were located in the fundus-gastric body junction (6.4%), and 1 tumor was located in the ridge between the gastric body and the fundus (1%) (Table 3). All patients completed EFTR treatment, and the operation success rate was 100.0%. The wound closure time and number of titanium clips used were significantly lower in the preclosure group than in the nonclosure group (P < 0.05); the number of fasting days, length of postoperative hospital stay, and need for an indwelling gastric tube did not significantly differ between the two groups (Table 4). The average wound closure time was 8.8 minutes (3-20 minutes). The average hospital stay was 6 days (4-9 days), and no delayed bleeding or peritonitis symptoms occurred during hospitalization.

| Group | Tumor site [n (%)] | ||||||

| Gastric body | Gastric fundus | Fundus-gastric body junction | Posterior wall of the cardia | Ridge between the gastric body and fundus | Gastric angle | Gastric antrum | |

| Preclosure group (n = 54) | 19 (35.2) | 32 (59.2) | 3 (5.6) | ||||

| Non-preclosure group (n = 40) | 14 (35.0) | 18 (45.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Group | Wound closure time (min) | Number of titanium clips used (pcs) | Number of fasting days (days) | Length of postoperative hospital stay (days) | Need for an indwelling gastric tube [n (%)] |

| Preclosure group (n = 54) | 6.69 ± 2.10 | 8.93 ± 2.23 | 3.61 ± 0.78 | 6.41 ± 1.31 | 9 (16.7) |

| Non-preclosure group (n = 40) | 11.65 ± 3.78 | 12.05 ± 4.49 | 3.73 ± 0.84 | 6.13 ± 1.06 | 13 (32.5) |

| χ2/t value | 7.479 | 4.043 | 0.672 | 1.116 | 3.213 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.504 | 0.267 | 0.073 |

All specimens were sent for pathological analysis. All 94 specimens were obtained via EFTR, the mucosal surface and serosal surface of the tumor were clearly visible, and no residual tumor or ectopic pancreatic tissue was found at the resection margin of all lesion tissues, indicating a complete resection rate of 100.0%. Pathological analysis revealed 73 (77.7%) cases of stromal tumors, 14 cases (14.9%) of leiomyomas, 2 cases (2.2%) of calcified fibrous tumors, 1 case (1%) of ectopic pancreatic tissue, 1 case of a spindle cell tumor (1%), 2 cases (2.2%) of schwannomas, and 1 case (1%) of lipoma (Table 5).

| Group | Pathological type [n (%)] | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | Leiomyoma | Ectopic pancreatic tissue | Calcified fibrous tumor | Spindle cell tumor | Schwannoma | Lipoma | |

| Preclosure group (n = 54) | 43 (79.6) | 7 (12.9) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Non-preclosure group (n = 40) | 30 (75.0) | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||

With advances in endoscopic and EUS techniques and increased health awareness, the rate of detection of gastrointestinal SMTs has increased significantly[7]. Generally, the clinical symptoms of SMTs with a diameter of less than 2 cm are not obvious, and such SMTs are mostly discovered incidentally during endoscopic examinations. In the past, regular en

In recent years, ESD-based EFTR has gradually become an emerging method for treating gastric SMTs. EFTR is an endoscopic surgery in which active perforation is used for full-thickness resection of the diseased gastric wall, regardless of the tumor depth. Compared with laparoscopic and laparotomic surgery, EFTR is less traumatic, and patients recover faster after surgery[10]. Andalib et al[11] reported 25 cases of patients with gastric SMTs treated with EFTR, achieving a complete resection rate of 100% and a complete suture rate of 100%. The surgical success rate in this study was 100%, which is consistent with that reported by Zhang et al[12] in a similar study.

During EFTR surgery, it is crucial to ensure that the perforation site is properly closed. A variety of closure methods are available to achieve this aim. For small defects, metal clips can be directly used for closure. However, larger defects require much more complete closure with highly complicated defect closure devices or instruments. In recent years, several novel methods, such as over-the-scope clip and OverStitch closure, have been applied to repair gastrointestinal damage and bleeding[13-15]. In addition, full-thickness resection devices, which combine EFTR and closure, have also been used. Although many methods and devices have been developed in recent years for gastrointestinal wall closure, most of these methods require complex or specialized equipment and are technically challenging. Thus, given its simplicity, metal clip closure still plays an important role in wound closure in EFTR.

In our study, 94 patients with gastric SMTs underwent EFTR surgery. It is critical to maintain a clear endoscopic FOV during surgery. However, once the gastric wall is actively perforated, the FOV becomes limited, seriously impacting the surgical process. To solve this problem, Jeon et al[16] were first to report the use of dental floss-assisted ESD for the treatment of gastric mucosal lesions, in 2009. This method not only improves the view of the operational field but also achieves good results in practical applications. Soga et al[17] subsequently applied extracorporeal dental floss traction to EFTR in the treatment of gastric SMTs and achieved satisfactory results. During full-thickness resection in EFTR, the titanium clips are pulled by the dental floss to reduce the defect to a line, not only reducing the tension on the defect but also making it easier to close with the titanium clips, thus shortening the closure time[18]. This method requires only titanium clips and dental floss, which are common clinical endoscopic items that are easy to obtain, simple to use, and inexpensive. In this study, we demonstrated that with the assistance of dental floss traction, the gastric wall defect could be closed before complete tumor resection. This technique is simple and effective, and it is superior to using complex or specialized devices alone to close defects after EFTR. The advantages of this new technology are reflected in four main aspects. First, the defect can be effectively closed by dental floss traction. Second, closing the defect before complete tumor detachment can effectively prevent the tumor from falling into the abdominal cavity both before and after complete tumor resection. Third, pseudo-occlusion due to inversion of the incision folds after complete tumor resection can be effectively prevented. Finally, the tension of the surrounding tissues and the entry of gas into the abdominal cavity can be significantly reduced, thereby reducing related complications and shortening the duration of the operation. These conclusions are consistent with those of relevant domestic studies.

In summary, when the EFTR technique is used to treat gastric SMTs, the use of external dental floss traction with en

| 1. | Standards of Practice Committee; Faulx AL, Kothari S, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Shaukat A, Qumseya BJ, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in subepithelial lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1117-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nishida T, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Nishida Y. Submucosal tumors: comprehensive guide for the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:479-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharzehi K, Sethi A, Savides T. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Subepithelial Lesions Encountered During Routine Endoscopy: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2435-2443.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Qin XY, Cai MY, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Zhang YQ, Qin WZ, Hu JW, Liu JZ. Endoscopic full-thickness resection without laparoscopic assistance for gastric submucosal tumors originated from the muscularis propria. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2926-2931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dalal I, Andalib I. Advances in endoscopic resection: a review of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR) and submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER). Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nishida T, Hirota S, Yanagisawa A, Sugino Y, Minami M, Yamamura Y, Otani Y, Shimada Y, Takahashi F, Kubota T; GIST Guideline Subcommittee. Clinical practice guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in Japan: English version. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:416-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim IH, Kim IH, Kwak SG, Kim SW, Chae HD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) of the stomach: a multicenter, retrospective study of curatively resected gastric GISTs. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2014;87:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li J, Meng Y, Ye S, Wang P, Liu F. Usefulness of the thread-traction method in endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric submucosal tumor: a comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2880-2885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aghdassi A, Christoph A, Dombrowski F, Döring P, Barth C, Christoph J, Lerch MM, Simon P. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Clinical Symptoms, Location, Metastasis Formation, and Associated Malignancies in a Single Center Retrospective Study. Dig Dis. 2018;36:337-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cai MY, Martin Carreras-Presas F, Zhou PH. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2018;30 Suppl 1:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Andalib I, Yeoun D, Reddy R, Xie S, Iqbal S. Endoscopic resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in North America: methods and feasibility data. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1787-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang Y, Meng Q, Zhou XB, Chen G, Zhu LH, Mao XL, Ye LP. Feasibility of endoscopic resection without laparoscopic assistance for giant gastric subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer (with video). Surg Endosc. 2022;36:3619-3628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sarker S, Gutierrez JP, Council L, Brazelton JD, Kyanam Kabir Baig KR, Mönkemüller K. Over-the-scope clip-assisted method for resection of full-thickness submucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2014;46:758-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mosquera-Klinger G, Torres-Rincón R, Jaime-Carvajal J. Endoscopic closure of gastrointestinal perforations and fistulas using the Ovesco Over-The-Scope Clip system at a tertiary care hospital center. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2019;84:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Piyachaturawat P, Mekaroonkamol P, Rerknimitr R. Use of the Over the Scope Clip to Close Perforations and Fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020;30:25-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jeon WJ, You IY, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ. A new technique for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: peroral traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Soga K, Shimomura T, Suzuki T, Tei T, Usui T, Inagaki Y, Kassai K, Itani K. Usefulness of the modified clip-with-line method for endoscopic mucosal treatment procedure. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2018;27:317-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kobayashi Y, Kono S, Iwatsuka K, Yagi-Kuwata N, Kusano C, Fukuzawa M, Moriyasu F. Usefulness of a traction method using dental floss and a hemoclip for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a propensity score matching analysis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/