INTRODUCTION

Gastric retention refers to the accumulation of unemptied contents and volume in the stomach, leading to impaired nutrient absorption and an elevated risk of complications, including reflux and aspiration, significantly raising mortality rates of patients[1]. Generally, gastric retention poses a substantial clinical challenge for patients undergoing enteral nutrition (EN) by virtue of a nasogastric tube, as it often disrupts EN delivery, delays nutritional support, and heightens the risk of malnutrition and infection. Monitoring gastric residual volume (GRV) is an established and widely used strategy for assessing gastric emptying capacity and preventing reflux and aspiration pneumonia in EN patients[2]. While GRV monitoring is widely employed, its clinical application varies significantly, owing to the lack of consensus on the optimal GRV threshold and monitoring frequency. Surveys have revealed that nurses employ highly inconsistent GRV thresholds (ranging from 200 mL to 500 mL) to determine when to pause EN, reflecting the absence of a standardized approach in clinical practice[3,4]. Such inconsistency has contributed to unnecessary interruptions in EN, which negatively affect patient outcomes. For instance, Wang et al[5] observed that individuals with interrupted EN exhibited a threefold increase in malnutrition risk, a 30% higher probability of prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and a 50% higher risk of extended overall hospitalization. The outcomes above point to the pressing necessity of establishing refined, evidence-supported management protocols for gastric retention.

Current management strategies for gastric retention face several critical limitations. A major issue is the over-reliance on fixed GRV thresholds as the sole criterion for EN interruption, despite evidence indicating that GRV alone is a poor predictor of aspiration risk[6]. This practice often results in unnecessary EN suspensions, disrupting nutritional support and delaying patient recovery. Traditional GRV measurement using syringe aspiration is another limitation, as it is prone to procedural contamination, underestimation of gastric contents, and increased nursing workload[7]. Additionally, the variability in GRV monitoring intervals, with guidelines recommending assessments every 4 to 8 hours, creates inconsistencies in clinical practice and leads to fragmented patient care[8]. Addressing these limitations requires evidence-based protocols that incorporate multiple clinical indicators beyond GRV alone, as well as more efficient and standardized measurement methods.

This review addressed these gaps by proposing a novel, three-pronged management approach that integrated general interventions, pharmacological interventions, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatments into a comprehensive strategy for managing gastric retention. Unlike prior research focusing on isolated measures, this review highlighted the synergistic potential of combined approaches to optimize patient outcomes. It also promoted bedside ultrasound as a safer, more accurate alternative to syringe aspiration for GRV monitoring, addressing key limitations of current practice. By advancing evidence-based protocols that unified intervention strategies and measurement methods, this review aimed to minimize EN interruptions, optimize nutritional support, and promote patient recovery.

OVERVIEW OF GASTRIC RETENTION

Diagnostic criteria

There is still no consensus among scholars, both domestically and internationally, on the diagnostic criteria for GRV in patients with EN[5,9,10]. The diagnostic criteria for gastric retention in China is that the GRV exceeds 200 mL or is greater than 50% of the infused volume[10-12]. High GRV is defined when GRV > 250 mL persists in two consecutive GRV measurements or when GRV surpasses 50% of the feeding amount administered in the prior 2 hours[13]. As indicated by Chinese guidelines[12], for intermittent nasogastric feeding, the GRV should be checked before each feeding, whereas for continuous nasogastric feeding, GRV should be assessed every 4-8 hours. Prokinetic agents can be used when gastric retention exceeds 250 mL; EN should be paused when GRV exceeds 500 mL, and the volume will be reassessed 4 hours later. The American Society for Parenteral and EN[8] suggested that EN should remain uninterrupted when GRV is under 500 mL. Moreover, routine GRV monitoring is not recommended for critically ill patients receiving EN unless patients experience symptoms of gastrointestinal intolerance, including diarrhea, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, or vomiting. As per the guidelines of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism[14], GRV monitoring is advised during the initiation and modification phases of EN, and EN is delayed if GRV exceeds 500 mL within 6 hours. The GRV between 250 mL and 500 mL, as recommended by the Canadian Critical Care Nutrition Guidelines[15], is acceptable in critically ill sufferers with EN, with GRV checked every 4 or 8 hours. A previous multicenter survey conducted in China[16] revealed that 150 mL (25.2%) and 200 mL (44.6%) were the most commonly applied GRV thresholds. The majority of nurses (84.3%) immediately suspend nasogastric feeding upon detecting high GRV. A systematic review[17] finds no significant correlation between GRV (200-500 mL) and aspiration or pneumonia, with a limited ability to predict aspiration-related pneumonia. However, such results may lead to unnecessary interruptions in nutritional supply. Therefore, EN is recommended to be maintained if GRV is below 500 mL, provided there are no other gastrointestinal intolerance symptoms. Some studies[17-19] have investigated less frequent GRV monitoring, demonstrating that it can decrease contamination risk, fluid exposure, and healthcare staff workload without increasing the incidence of complications. Based on the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines[14] and domestic expert consensus[20], GRV should be monitored every 4 hours for individuals prone to aspiration or gastrointestinal intolerance. Additionally, literature has reported[21,22] that for high-risk aspiration patients, the methods of feeding should be transitioned to nasojejunal feeding, with parenteral nutrition provided as a supplement if GRV results in inadequate EN. Overall, there is still no consensus on GRV thresholds and the monitoring frequency across different regions. The phenomenon of artificial interruptions of EN in domestic settings is more pronounced. Relying solely on GRV thresholds to guide EN may be one-sided, and the guidance should be conducted on GRV thresholds combined with the gastrointestinal symptoms of patients.

Measurement methods

GRV monitoring provides dynamic insights into gastrointestinal motility and EN tolerance, and the volume of gastric contents can be measured and calculated using radionuclide imaging, aspiration, ultrasound, or Brix meter[5]. Radionuclide imaging is recognized as the gold standard for GRV measurement. Nevertheless, the high technical requirements and costs of this method render it unsuitable for routine bedside monitoring[20]. In contrast, bedside gastrointestinal ultrasound monitoring offers high accuracy for GRV assessment while maintaining the continuity of EN. Furthermore, this technique has emerged as a new technique in the implementation of EN due to its multiple advantages, such as ease of operation and non-invasiveness[23]. The gastric antrum is the optimal site for ultrasound monitoring, with ideal images achievable in 90%-100% of patients. Moreover, even when the residual volume is minimal, gastric contents can still be clearly observed[24]. Syringe aspiration is a widely applied non-invasive measurement technique due to its simplicity and time efficiency; however, it poses a risk of contaminating the nutritional formula[20]. Ohashi et al[25] discovered that aspiration, a non-standardized measurement method, was affected by various factors during practice, resulting in significant discrepancies between actual values and measured volumes. GRV monitoring may be influenced by multiple factors, such as the diameter of the nasogastric tube, syringe size, patient position, and operator’s technique. Consequently, syringe aspiration may not accurately reflect the true GRV. Xiang et al[26] demonstrated no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between the bedside ultrasound method and the aspiration method by comparing these two methods in monitoring the feasibility and safety of GRV. However, the operation time for the bedside ultrasound method was markedly shorter than that for the aspiration method, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.01). Bedside ultrasound can effectively assess GRV, shorten operation time, and reduce the workload of nurses. Despite this, syringe aspiration is the predominant method used by domestic nurses to measure GRV[16]. To optimize EN management and minimize interruptions caused by routine GRV monitoring, it is recommended to gradually transition from syringe aspiration to gastric ultrasound as the preferred monitoring method.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR PATIENTS WITH EN COMPLICATED WITH GASTRIC RETENTION

Identification and management of contributing factors

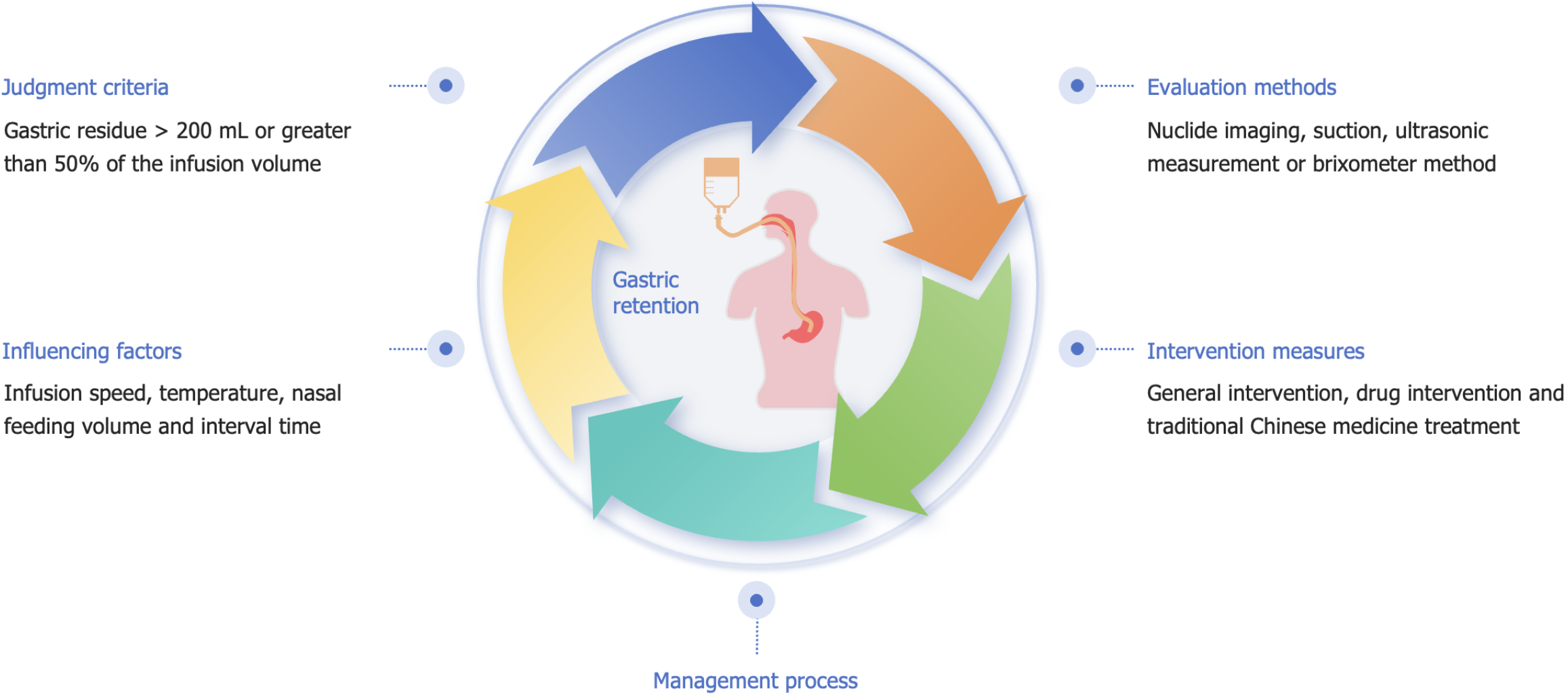

Jin[27] and Guo[28] identified several risk factors associated with gastric retention in critically ill patients receiving EN via nasogastric tubes. These factors include brainstem lesions, involvement of the autonomic nervous system, a history of mechanical ventilation and shock, Glasgow Coma Scale score < 8, mild hypothermia treatment, reduced bowel sounds, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, abnormal blood glucose, hypoproteinemia, and advanced age. Yu et al[29] monitored daily GRV in 63 critically ill patients with intracerebral hemorrhage undergoing EN. They observed a positive correlation between GRV and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scoring system (P < 0.05), along with a significant association between GRV and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (P < 0.01). The trend in GRV changes can indirectly indicate the disease progression and prognosis of critically ill patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. The occurrence of gastric retention[21] has been reported to be correlated with the rate of EN infusion, with a remarkable increase in the risk of gastric retention when the infusion rate exceeds 100 mL/h. Feng et al[17] revealed that the appropriate nasogastric feeding volume and interval were crucial factors affecting gastric retention (Figure 1). The incidence of reflux and aspiration can be notably reduced through a single feeding volume of < 450 mL, an interval of approximately 5 hours, and maintaining a semi-recumbent position for at least 30 minutes after feeding. A meta-analysis[30] shows that intermittent nasogastric feeding using gravity or EN pumps for 30-60 minutes per session, 4-6 times per day, does not affect gastric retention, aspiration pneumonia, or nutritional outcomes compared to continuous nasogastric feeding. Cheng[31] tested the heater’s clamping position across different speeds and investigated the temperature regulation of the EN solution at the outlet. A heating model, Y = 15.952 + 0.147X, was developed to ensure that the solution entering the body remains at 37°C, with Y indicating distance and X representing speed. A standardized EN heating system can effectively reduce the incidence of gastric retention. As revealed by a study[27], the incidence of gastric retention in neurocritically ill patients is time-dependent, peaking within the first week (68% of patients with gastric retention) and gradually decreasing thereafter. Additionally, gastric retention can still occur in the second and third weeks. Such results may be related to the body's intense stress response during the acute phase. Yu[32] developed a risk assessment model for gastric retention and conducted an evaluation. In this model, the risk levels were assigned based on the number of risk factors, with higher levels indicating a greater need for attention during the nursing process. Predictive care can then be provided according to the identified risk factors. Overall, the key factors affecting gastric retention include infusion rate, temperature, nasogastric feeding volume, and intervals. Given the ensuring daily caloric supply, adjustments can be implemented according to the sufferers’ tolerance and response. Although the risk assessment model for gastric retention is still underdeveloped, further refinement and clinical application can enhance its ability to assess risks, guiding nurses in taking timely prevention and intervention measures.

Figure 1 Assessment and intervention strategies for gastric retention in nasogastric feeding.

Development of standardized procedures

An earlier study[33] suggested that 26% of EN interruptions could be avoidable. Reducing the frequency of EN interruptions and ensuring continuous, effective EN are key factors in improving the prognosis of critically ill sufferers with gastric retention. Chen and Wang[34] found that standardized management procedures for gastric retention could improve EN feeding target achievement rates and reduce prokinetic agent usage, while not notably affecting aspiration incidence. The specific procedures varied depending on GRV levels: (1) If GRV was < 200 mL, a 20 mL/h increment in infusion rate was applied, ensuring the rate did not exceed 120 mL/h; (2) If the GRV was between 200 mL and 350 mL, the original infusion rate was cut in half; (3) If the GRV ranged from 350 mL to 500 mL, the rate was decreased to 25% of the original speed; (4) When the GRV reached or exceeded 500 mL, the infusion was halted and the GRV was reassessed after 6 hours [referred to steps (1), (2), (3)]; (5) if the GRV was ≥ 500 mL and the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 score was < 5, a switch to post-pyloric feeding was conducted; and (6) If the GRV was ≥ 500 mL and the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 score was ≥ 5, 10 mg of metoclopramide (a prokinetic agent) was administered intramuscularly. Yang[35] recorded GRV and EN infusion rates using EN information management software, with notifications set at 6-hour intervals to remind nursing staff to monitor gastric retention. This software could automatically calculate the infusion rate and total volume, effectively reducing the number of EN interruptions due to gastric retention. Chen et al[36] improved the EN tolerance assessment form, incorporating factors such as abdominal distension, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, bowel sounds, gastric retention, aspiration, and drug contraindications as indicators of EN intolerance in critically ill individuals. Additionally, the corresponding grades and nursing measures were assigned, which contributed to standardizing and regulating the infusion rates of EN solutions and the use of prokinetic agents. As indicated by Jiang et al[37], GRV levels were categorized into various risk grades for gastric retention, and the corresponding operational procedures were systematically standardized with quantitative steps. Such procedures not only improved the feeding target achievement rates, but also effectively reduced GRV. Li et al[38] proposed the implementation of sequential EN intervention based on feedforward control in critically ill patients. This intervention began with the screening of high-risk patients, who were highlighted with red markers. Treatment was then carried out according to the assigned risk grades, allowing for the efficient allocation of nursing resources and reducing the occurrence of complications. In summary, the standardized nutrition support procedures have transformed passive management into proactive intervention, fully realizing standardized and regulated nursing. Additionally, these procedures have also enhanced overall enteral care to achieve effective dynamic interventions, thereby improving EN tolerance in patients.

General interventions

Position management is a fundamental measure to prevent gastric retention in individuals suffering EN. A systematic review[39] revealed that maintaining a head-of-bed elevation of ≥ 30° during nasogastric feeding can lower the likelihood of gastric retention, reflux, aspiration, pneumonia and other complications, thereby improving the safety of EN. These outcomes matched the conclusions drawn in Hannah’s study[4]. Liu et al[40] compared the relationship between three varying intervals (30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 90 minutes) of head-of-bed elevation (30°-45°) and GRV, indicating that maintaining a 60-minute elevation significantly promoted gastric digestion and emptying. Elevating the head of the bed to 40°-45° led to the highest safety of nasogastric feeding and the lowest risk of gastric retention. Yang et al[41] also recommended head-of-bed elevation to 45° in cluster nursing for preventing gastric retention in ICU patients. Additionally, semi-recumbent and right lateral positions were adopted alternately, along with abdominal massage. According to a previous article[42], abdominal massage can not only enhance vagus nerve activity, but also promote gastrointestinal motility. Furthermore, it can induce reflexive and mechanical effects on the gastrointestinal tract by altering intra-abdominal pressure, thereby promoting gastric emptying. Several systematic reviews[43,44] also confirmed that gastric retention in EN patients can be effectively minimized through abdominal massage. Hence, both position management and abdominal massage are safe, simple, and feasible interventions suitable for broad application in clinical practice. However, it should be noted that abdominal massage mainly targets the intestines, with the limited direct effect on the stomach. Further research and exploration in this area are warranted. Limb activities[28,41,45] have been illustrated to significantly promote gastrointestinal function and reduce gastric retention. These activities include passive movement, active movement in bed, position changes, and bedside activities. A study by Cao et al[45] explored the application of stage early upright mobilization in critically ill individuals. They found that the incidence of EN interruption due to increased GRV was markedly lower in the observation group than in the control group, demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Pharmacological interventions

Erythromycin is known for its role as a macrolide antibiotic and motilin receptor agonist. It can strongly promote peristalsis in the stomach and proximal small intestine, induce significant antral contractions, and then accelerate gastric emptying. Apart from its prokinetic effects, erythromycin exhibits antibacterial properties, which may contribute to reducing the risk of gastrointestinal infections in certain cases[46]. Metoclopramide, a dopamine receptor antagonist, influences the chemoreceptor trigger zone centrally and gastric smooth muscle peripherally. Currently, the United States Food and Drug Administration has approved metoclopramide as the sole medication for treating gastric retention, with a recommendation for use limited to less than three months. A recommended dose of metoclopramide is 5-10 mg, administered three times daily[2]. Domperidone, a peripheral dopamine-2 receptor antagonist, can promote motility in the upper gastrointestinal tract, particularly the stomach. Moreover, it is effective in alleviating symptoms, such as vomiting and nausea[20].

TCM treatment

Various treatment methods exist in TCM for gastric retention, and their efficacy and mechanisms have gradually gained recognition[22]. Shan et al[47] stated that individuals with mechanical ventilation were treated with metoclopramide injection at bilateral Zusanli acupoints combined with abdominal massage. They discovered that the experimental group displayed a significantly lower incidence of gastric retention, abdominal distension, and vomiting than the controls (P < 0.05). Besides, a notable decrease was observed in the abdominal circumference after treatment. The above results confirmed the effectiveness of this combined method in reducing the incidence of gastric retention and related symptoms. As indicated by Zhao and Tang[48], elderly patients with nasogastric feeding were treated with the Jianpi Tongwei Fang application at the Neiguan acupoint, followed by 5 minutes of moxibustion at the application site and an additional 5 minutes at the Zusanli acupoint. They demonstrated that the experimental group achieved superior efficacy in nasogastric feeding as against the control group, accompanied by a significant reduction in gastrointestinal reactions, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension (P < 0.05). These results verified the effectiveness of integrating Chinese herbal medicine with moxibustion thermal stimulation applied to acupoints. Feng et al[49] followed the midnight-noon ebb-flow theory of TCM and performed massages on critically ill sufferers with EN based on the twelve meridians flow of Qi and blood. They uncovered that in comparison with the control group, the experimental group presented with considerably reduced gastric retention volume, increased feeding volume, and decreased incidence of aspiration pneumonia, with a notable difference in statistics (P < 0.05). Hu et al[50] applied auricular acupressure to ICU patients with EN, selecting a combination of five acupoints: Sympathetic, subcortex, brainstem, stomach, and spleen, guided by their clinical experience. Their results presented that the nutritional risk scores and GRV were evidently decreased in the experimental group, showing statistically notable differences (P < 0.05), inferring a positive effect on alleviating the symptoms of gastric retention and improving nutritional status. In the investigation led by Hu et al[51], elderly sufferers with gastric retention were treated with press needles combined with abdominal hot compresses (Figure 2). Stimulating specific acupoints combined with abdominal hot compresses can promote qi and blood circulation, alleviate spleen and stomach qi deficiency syndrome, and effectively enhance gastric emptying.

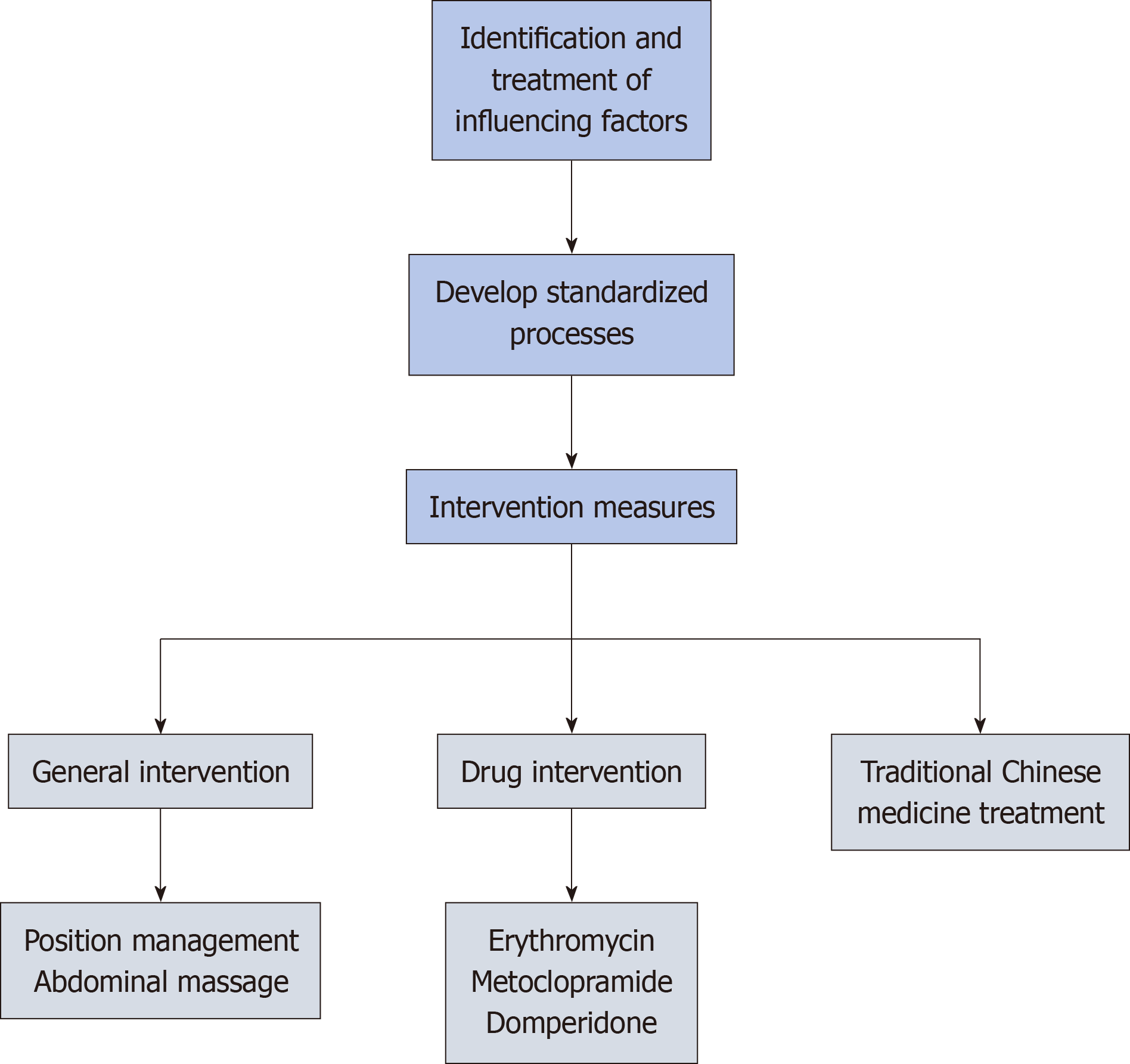

Figure 2 Multidimensional management of gastric retention in enteral nutrition.

Overall, TCM treatments have shown positive results in the treatment of gastric retention. However, most of the studies mentioned above involve small sample sizes, and lack detailed TCM syndrome differentiation and long-term follow-up data. Therefore, larger sample sizes and multicenter clinical studies required in the future to validate the efficiency and safety of TCM treatments, with the aim of promoting the standardization and normalization of TCM in treating gastric retention.

CONCLUSION

This study systematically reviewed and analyzed the literature on gastric retention in adult patients with EN by nasogastric tubes, comparing the thresholds and measurement methods used domestically and internationally. The findings highlight the importance of a comprehensive "three-pronged" management strategy that integrates non-pharmacological, pharmacological, and TCM-based interventions. This strategy addresses the limitations of single-intervention models, providing a patient-centered strategy to reduce EN interruptions, enhance nutritional support, and prevent complications such as aspiration pneumonia.

Our findings have significant clinical implications. Specifically, incorporating the "three-pronged" strategy into routine care can improve gastric retention management and reduce unnecessary EN interruptions. The adoption of bedside ultrasound for GRV monitoring is recommended as a safer, more efficient alternative to syringe aspiration. To support clinical translation, hospitals should acquire portable ultrasound devices, train healthcare staff on bedside ultrasound procedures, and establish protocols for EN suspension and resumption. In addition, personalized care pathways should be developed to tailor interventions based on GRV thresholds and gastrointestinal symptoms, allowing for individualized treatment. Furthermore, strengthening post-discharge care is also essential to ensure patients and caregivers receive guidance on nutritional support and symptom monitoring, thereby reducing readmissions and promoting better long-term outcomes.

Despite recent progress in the management of gastric retention, numerous challenges remain. Future investigations should concentrate on large-scale, multicenter clinical trials to verify the effect and safety of different management strategies, promoting the standardization and normalization of gastric retention management. Additionally, the development of individualized treatment plans and comprehensive intervention measures is crucial for improving clinical outcomes and the quality of life of patients. Furthermore, post-discharge continuity of care should also be emphasized to provide more precise guidance for clinical practice.