Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.114628

Revised: October 1, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 4.9 Hours

The vascular endothelial glycocalyx (VEG) plays a critical role in maintaining va

To determine whether perioperative DEX attenuates surgical inflammation-in

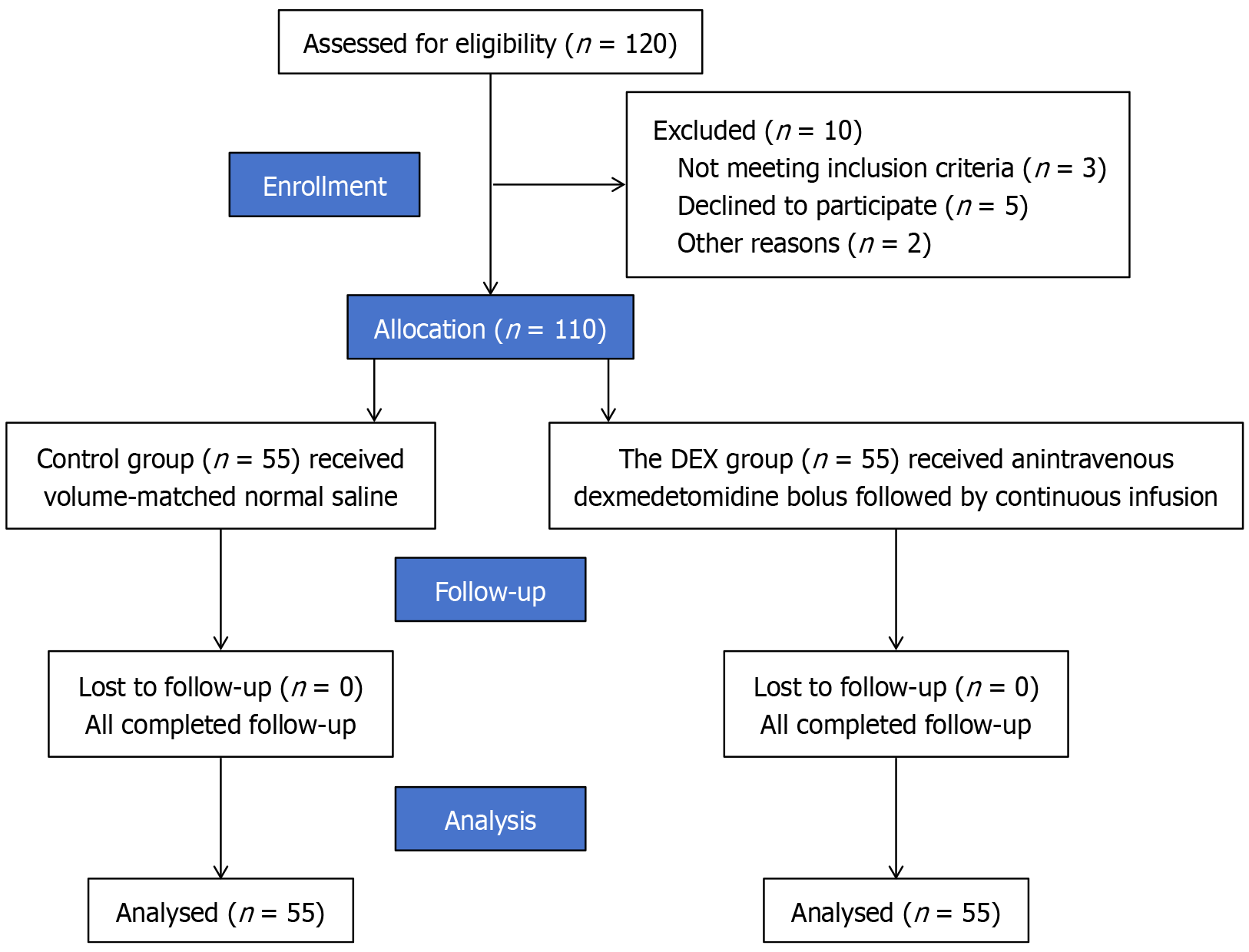

This was a prospective, single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China. A total of 110 patients undergoing elective gastric or colorectal tumor resection were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive intraoperative DEX or saline placebo. Anesthesia and analgesia were standardized across groups. The primary outcome was plasma syndecan-1 concentration, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx injury, measured at four perioperative timepoints (T0-T3). Secondary outcomes included inflammatory biomarkers [interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, C-reactive protein, heparan sulfate], microcirculatory parameters [perfused vessel density (PVD), flow index, P(v-a)CO2, lactate], and clinical endpoints [extubation time, opioid use, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores, Quality of Recovery-15 Questionnaire (QoR-15), length of stay, and 30-day complications]. Postoperative complications were defined by Clavien-Dindo criteria and adjudicated by blinded investigators. The trial was registered prospectively (ChiCTR2500109633) and powered to detect a clinically meaningful difference in syndecan-1 levels.

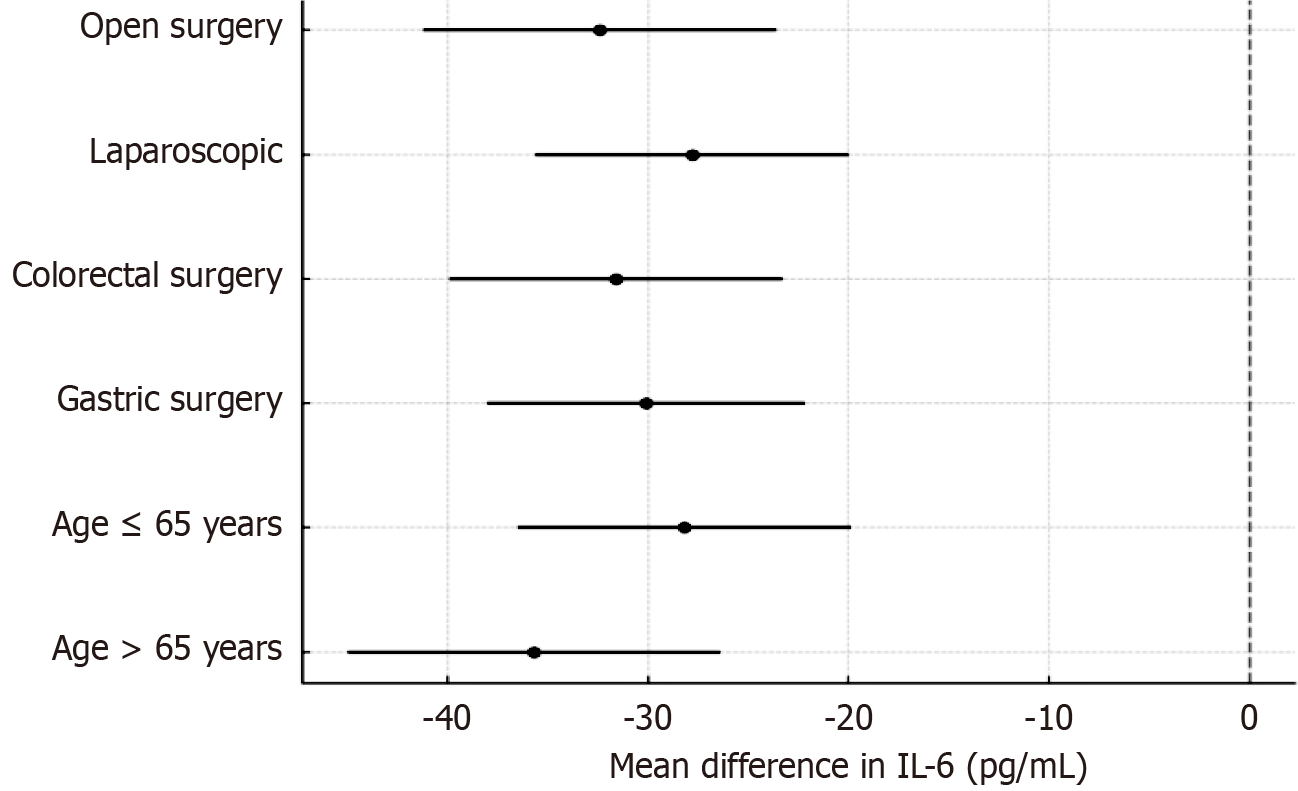

A total of 110 patients were randomized equally to the DEX or control group, with well-balanced baseline characteristics. Compared with controls, DEX significantly reduced postoperative infections (7% vs 16%) and intensive care unit admissions (7% vs 13%), shortened extubation time (13.1 ± 3.0 minutes vs 18.4 ± 4.0 minutes; P < 0.001), and decreased opioid use (23.1 ± 5.0 mg vs 27.3 ± 6.0 mg; P = 0.004) and VAS pain scores (P = 0.002). At abdominal closure, DEX attenuated endothelial glycocalyx injury, as evidenced by lower plasma syndecan-1 (44.72 ± 7.10 ng/mL vs 48.73 ± 6.26 ng/mL; P = 0.002) and heparan sulfate levels (P = 0.001). IL-6 was significantly reduced at 24 hours (110.77 ± 29.72 pg/mL vs 138.86 ± 35.95 pg/mL; P < 0.0001) and positively correlated with syndecan-1 (r = 0.71). Microcirculatory function improved with DEX, including higher PVD (21.40 ± 3.50 mm/mm² vs 19.94 ± 2.93 mm/mm²; P = 0.019), increased flow index, lower P(v-a)CO2 (P < 0.001), and reduced lactate (P = 0.003). DEX also improved recovery outcomes, with higher QoR-15 scores (P = 0.001), shorter hospital stays (6.49 ± 1.29 days vs 7.29 ± 1.59 days; P = 0.005), and fewer overall 30-day complications (12.7% vs 30.9%; P = 0.036). Receiver operating characteristic analysis identified syndecan-1 > 45 ng/mL at abdominal closure as a potential predictor of postoperative complications (area under the curve = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.59-0.76), and multivariable analysis showed a near-significant association (OR = 2.88, P = 0.057). Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent anti-inflammatory and endothelial-protective effects of DEX across age and surgical approach strata.

Perioperative administration of DEX confers significant endothelial-protective effects by mitigating glycocalyx degradation, suppressing systemic inflammation, and promoting enhanced postoperative recovery. These findings support its clinical utility as a valuable adjunctive therapy in the perioperative management of patients undergoing oncologic gastrointestinal surgery.

Core Tip: This randomized controlled trial demonstrates that perioperative dexmedetomidine (DEX) infusion attenuates vascular endothelial glycocalyx degradation (as evidenced by reduced syndecan-1 and heparan sulfate levels) and suppresses systemic inflammation in patients undergoing gastrointestinal tumor resection. These mechanistic benefits were associated with improved microcirculatory perfusion, reduced postoperative complications, and enhanced recovery, including shorter hospital stay. The study identifies syndecan-1 as a potential biomarker for perioperative risk stratification and supports the integration of DEX as an endothelial-protective adjunct within Enhanced Recovery after Surgery protocols for oncologic surgery.

- Citation: Zeng R, Tang CL, Zhao Y, Wang RX, Fang Y, Hu XW. Dexmedetomidine enhances recovery after gastrointestinal cancer surgery by protecting the endothelial glycocalyx: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(12): 114628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i12/114628.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i12.114628

The vascular endothelial glycocalyx (VEG) is a fragile, carbohydrate-rich layer composed of membrane-bound pro

Gastrointestinal oncologic resections, albeit curative, trigger a substantial systemic inflammatory response characterized by a sharp increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, notably interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These cytokines promote the release of matrix metalloproteinases (e.g., MMP-9), which enzymatically cleave core glycocalyx components such as syndecan-1 and heparan sulfate, ultimately compromising endothelial barrier function[3,4].

In cancer patients, this pathophysiological process is further amplified by tumor-derived exosomes carrying bioactive molecules like IL-6 and transforming growth factor-β. These nanovesicles facilitate paracrine signaling that exacerbates endothelial activation and glycocalyx degradation, creating a vicious cycle of vascular inflammation and injury[5-7]. The resulting endothelial dysfunction clinically manifests as increased vascular permeability, tissue edema, and a higher risk of postoperative complications, including pulmonary dysfunction, gastrointestinal paralysis, and renal impairment[8].

Emerging preclinical evidence indicates that certain anesthetic adjuvants, particularly the α2-adrenergic agonist dex

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to systematically evaluate whether perio

This prospective, single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, adhering to CONSORT guidelines and Good Clinical Practice principles. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Anhui Provincial Cancer Hospital (approval No. 2024014). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The trial was prospectively registered (ChiCTR2500109633, https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=221761) with a fixed sample size and no adaptive re-estimation clause. Investigators and statisticians remained blinded. Any mid-course recalculation would have required unblinding or revealing pooled variances, risking inflation of type-I error (“operational bias”). CONSORT and International Conference on Harmonization-E9 discourage unplanned sample-size changes because they compromise the pre-specified α-control; doing so would necessitate α-spending or Bayesian re-analysis, beyond our resources/timeframe. Our data and safety monitoring committee charter allowed an interim look only for safety signals (mortality/serious adverse events), not for efficacy or biomarker variance; those stopping boundaries were never crossed.

No important changes to trial methods, eligibility criteria, or outcome definitions were made after trial commencement.

This prospective trial enrolled 110 patients aged 18-75 years, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of II or III, who were scheduled for elective open or laparoscopic resection of gastric or colorectal neop

Key exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Bradycardia (resting heart rate < 50 beats per minute); (2) Hemoglobin level < 80 g/L or albumin < 25 g/L; (3) Chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2); (4) Hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh class C); (5) Active infection or ongoing immunosuppressive therapy; or (6) Coagu

Eligible participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated block randomization sequence (block size of 4) prepared by an independent biostatistician. Allocation concealment was strictly maintained through the use of sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes.

Intervention assignment was managed by an independent anesthesiologist not involved in subsequent patient care or outcome assessment. Patients allocated to the DEX group (n = 55) received an intravenous loading dose of 0.5 μg/kg over 10 minutes, followed by a continuous intraoperative infusion of 0.5 μg/kg/hour and a postoperative infusion of 0.05 μg/kg/hour via a patient-controlled intravenous analgesia pump. The control group (n = 55) received volume-matched normal saline administered identically. All study drugs were prepared in identical opaque syringes to ensure blinding.

To safeguard the blinding, all clinical staff, outcome assessors, and patients were masked to treatment allocation. Simi

The CONSORT flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

General anesthesia was induced using etomidate (0.2-0.3 mg/kg), propofol (2-2.5 mg/kg), sufentanil (0.3-0.5 μg/kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). Following induction, patients in the DEX group received a loading dose of DEX (0.5 μg/kg ad

Hemodynamic management was guided by cardiac output monitoring, complemented by real-time microcirculatory assessment using sidestream dark-field (SDF) imaging. Intraoperative hypotension, defined as mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg lasting ≥ 1 minute, was continuously recorded. Vasopressor administration followed a standardized protocol: Norepinephrine infusion was initiated for hypotension refractory to fluid optimization, while phenylephrine boluses were administered for transient pressure reductions. Both the incidence of hypotension and total vasopressor con

Standardized ventilation parameters were applied to all patients using volume-controlled ventilation with a tidal volume of 6-8 mL/kg predicted body weight. Respiratory rate was adjusted to maintain normocapnia (end-tidal CO2 35-40 mmHg) with positive end-expiratory pressure set at 5 cmH2O. Plateau airway pressures were maintained below 30 cmH2O, with particular attention to peak pressures during pneumoperitoneum. Recruitment maneuvers were performed as clinically indicated. Surgical positioning was standardized according to procedure type: Laparoscopic cases were performed in 15°-20° Trendelenburg position with pneumoperitoneum maintained at 12-14 mmHg, while open procedures were conducted in the supine position. Extreme or prolonged steep Trendelenburg positioning was avoided to minimize hemodynamic and microcirculatory disturbances.

Perioperative fluid management followed a standardized, goal-directed protocol based on stroke volume variation and cardiac output trends. Crystalloids (Ringer's lactate and Plasma-Lyte) served as primary maintenance fluids, while colloids (5% albumin) were administered only when clinically indicated for volume resuscitation. Total intraoperative fluid volumes, including crystalloids, colloids, and blood products, were recorded to avoid excessive fluid loading that could independently affect endothelial glycocalyx integrity.

Postoperative analgesia was provided through a patient-controlled intravenous analgesia system containing sufentanil (0.2 μg/kg) and ondansetron (0.4 mg/kg) in 150 mL saline, programmed for a 3 mL/h basal infusion with 3 mL bolus doses available every 30 minutes. The DEX group's solution additionally contained DEX at 0.05 μg/kg/hour.

Patient recruitment was conducted from March 2022 to August 2023. The final 30-day postoperative follow-up was completed in September 2023.

The primary outcome was the perioperative plasma concentration of syndecan-1, a specific biomarker of VEG injury. Measurements were taken at four predefined time points: Before anesthesia induction (T0), at abdominal closure (T1), and at 24 (T2) and 72 (T3) hours postoperatively, using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Abcam, ab235649).

Biomarkers of endothelial and inflammatory response: Plasma levels of the following biomarkers were assessed: Syn

Microcirculation and perfusion parameters: Microvascular function was evaluated using sublingual SDF imaging to measure the microvascular flow index, perfused vessel density (PVD), and the proportion of perfused vessels at T0, T1, and T2. Arterial lactate and the central venous-arterial carbon dioxide difference [P(v-a)CO2] were measured as complementary markers of global tissue perfusion.

Clinical recovery and postoperative complications: Recovery endpoints included time to extubation, cumulative opioid consumption (converted to intravenous morphine equivalents), postoperative pain scores on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), quality of recovery at 72 hours on the Quality of Recovery-15 Questionnaire (QoR-15), time to first ambulation, and length of hospital stay. Postoperative complications within 30 days included infection (e.g., surgical site infection, pneumonia), ileus, anastomotic leakage, and acute kidney injury (AKI). Data on intensive care unit (ICU) admission, 30-day readmission, and mortality were extracted from electronic medical records.

Anesthesia depth and sedation: Intraoperative anesthesia depth was monitored continuously using the Bispectral index. Postoperative sedation levels were assessed using the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale.

Postoperative complications were adjudicated by a blinded investigator using predefined criteria. Complications of Clavien-Dindo grade II or higher were included in the analysis.

Infectious complications: Pneumonia required radiographic confirmation; surgical site infection required antibiotic treatment; urinary tract infection required a positive culture.

AKI: Defined and staged according to KDIGO criteria[11] based on serum creatinine changes.

ICU admission: Defined as an unplanned transfer due to hemodynamic instability, respiratory failure, or need for invasive monitoring/therapy beyond routine care.

The sample size was determined based on the anticipated difference in syndecan-1 levels at the end of surgery (T1). Preliminary data and existing literature indicated that syndecan-1 levels in the control group at T1 would be approximately 65 ± 25 ng/mL. We considered a 30% relative reduction (approximately 19.5 ng/mL) in the DEX group to be clinically meaningful. With a two-sided α of 0.05 and 80% power, a total of 100 patients (50 per group) were required. To account for an estimated 10% dropout rate, 110 patients were enrolled.

Although the observed syndecan-1 levels at T1 were lower than projected (control group mean: 48.73 ng/mL), the standard deviation was also substantially smaller than expected (approximately 6-7 ng/mL vs the assumed 25 ng/mL). As a result, the study retained sufficient power to detect a clinically meaningful between-group difference, and no sample size recalculation was performed, in accordance with the pre-registered protocol and ethical approval. No interim analyses or stopping guidelines were predefined for this trial.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between groups using the independent-samples t-test, while non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median with interquartile range and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Longitudinal changes in biomarkers (e.g., syndecan-1, IL-6, TNF-α) were assessed using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with a time × group interaction, followed by Bonferroni post hoc corrections for multiple comparisons. Pearson correlation analysis was employed to examine associations between syndecan-1 and IL-6 levels, as well as between syndecan-1 and clinical outcomes such as postoperative length of stay. Area under the curve (AUC) analyses were conducted to evaluate cumulative inflammatory and endothelial injury burden over time. Effect sizes for continuous outcomes were expressed as mean differences with 95%CIs, and ORs with 95%CIs were reported for binary outcomes. A post hoc multivariable Logistic regression model was developed to explore the independent effect of DEX on 30-day postoperative complications, adjusting for baseline variables including age, comorbidities, and surgical approach.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed for the overall cohort, and stratified by treatment arm (DEX vs control), to assess whether DEX influences the predictive utility of syndecan-1 for postoperative complications.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A consecutive cohort of 110 patients undergoing elective gastrointestinal tumor resection was prospectively enrolled and randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either the DEX group (n = 55) or the control group (n = 55), with complete protocol ad

| Characteristic | DEX group (n = 55) | Control group (n = 55) | P value |

| Age (years) | 62.6 ± 9.1 | 61.9 ± 10.9 | 0.704 |

| Sex (male) | 36 (65.5) | 39 (70.9) | 0.682 |

| ASA II/III | 35 (63.6) | 40 (72.7) | 0.413 |

| Surgical duration (minute) | 188.3 ± 29.7 | 189.5 ± 28.5 | 0.829 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 330.9 ± 59.3 | 338.1 ± 55.0 | 0.703 |

| Hypertension | 22 (40.0) | 21 (38.2) | 0.849 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (21.8) | 14 (25.5) | 0.67 |

| CAD | 6 (10.9) | 5 (9.1) | 0.758 |

| Tumor site (gastric) | 25 (45.5) | 30 (54.5) | 0.446 |

| Tumor stage I-II | 31 (56.4) | 28 (50.9) | 0.566 |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 38 (69.1) | 35 (63.6) | 0.545 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 124.8 ± 14.7 | 126.2 ± 13.9 | 0.589 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.6 ± 3.2 | 38.1 ± 3.4 | 0.436 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 6.7 ± 3.0 | 0.483 |

| WBC count (× 109/L) | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 0.734 |

| Intraoperative deep hypotension | 6 (10.9) | 8 (14.5) | 0.580 |

| Duration of hypotension [minute, median (IQR)] | 3 (2-5) | 4 (2-6) | 0.420 |

| Norepinephrine use | 18 (32.7) | 20 (36.4) | 0.290 |

| Dose (μg/kg·minute) | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | |

| Phenylephrine use | 12 (21.8) | 14 (25.5) | 0.650 |

| Total intraoperative fluid volume [mL, median (IQR)] | 2450 (2100-2800) | 2500 (2200-2900) | 0.62 |

| Crystalloid volume (mL) | 2100 ± 450 | 2150 ± 470 | 0.59 |

| Colloid volume (mL) | 350 ± 120 | 360 ± 110 | 0.72 |

| Blood products | 3 (5.5) | 4 (7.3) | 0.69 |

| Trendelenburg tilt (°) | 17.5 ± 1.2 | 17.8 ± 1.4 | 0.481 |

| Intra-abdominal pressure (mmHg) | 13.1 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 0.355 |

The DEX group exhibited a lower incidence of postoperative infections (7% vs 16%), primarily driven by reduced pneumonia rates. No cases of anastomotic leakage were observed in either group. Ileus was rare and not significantly different between groups. ICU admissions were lower in the DEX group (7% vs 13%). The 30-day readmission and mortality were infrequent (1%-2%) and comparable across groups. DEX also shortened time to extubation (13.1 ± 3.0 0 minutes vs 18.4 ± 4.0 minutes; P < 0.001), reduced opioid consumption (23.1 ± 5.0 0 mg vs 27.3 ± 6.0 mg; P = 0.004), and lowered VAS pain scores (P = 0.002).

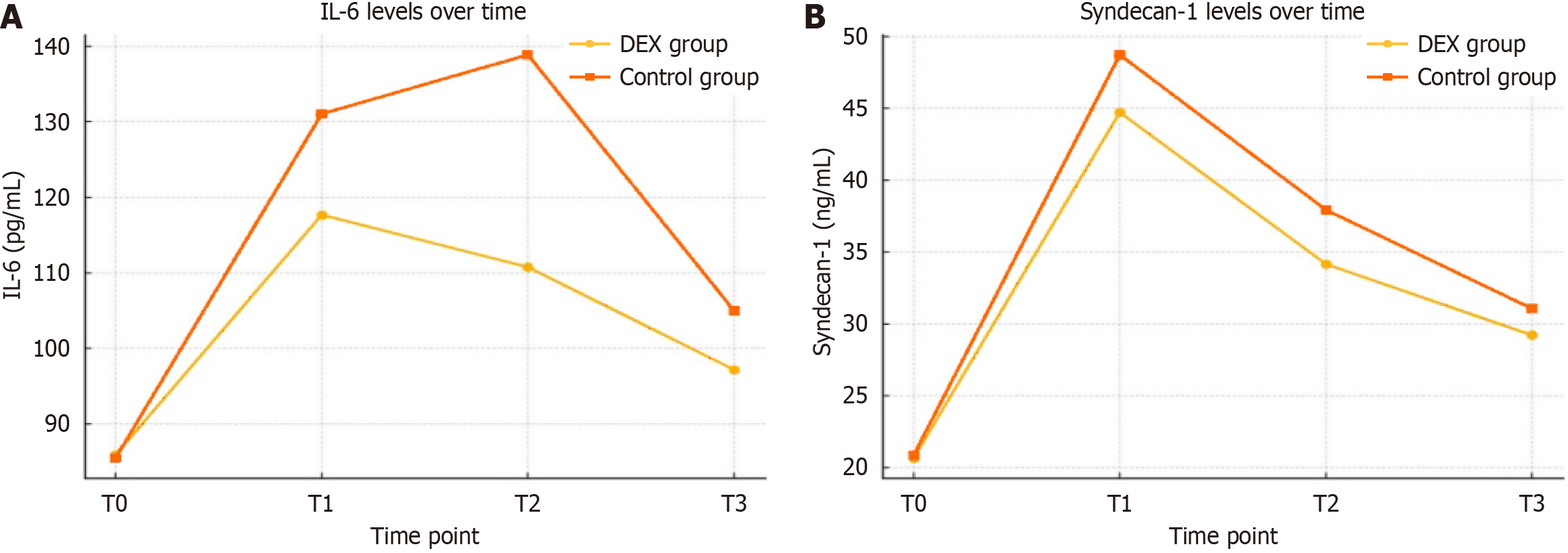

DEX demonstrated significant protective effects against perioperative glycocalyx degradation and inflammatory activation. At abdominal closure (T1), the DEX group exhibited significantly lower syndecan-1 concentrations (44.72 ± 7.10 ng/mL vs 48.73 ± 6.26 ng/mL; P = 0.002), representing an 8.2% attenuation of glycocalyx shedding. While lower than expected from prior estimates, the reduced inter-patient variability preserved the study’s statistical power. Similar trends were observed at T2 and T3 (P < 0.01).

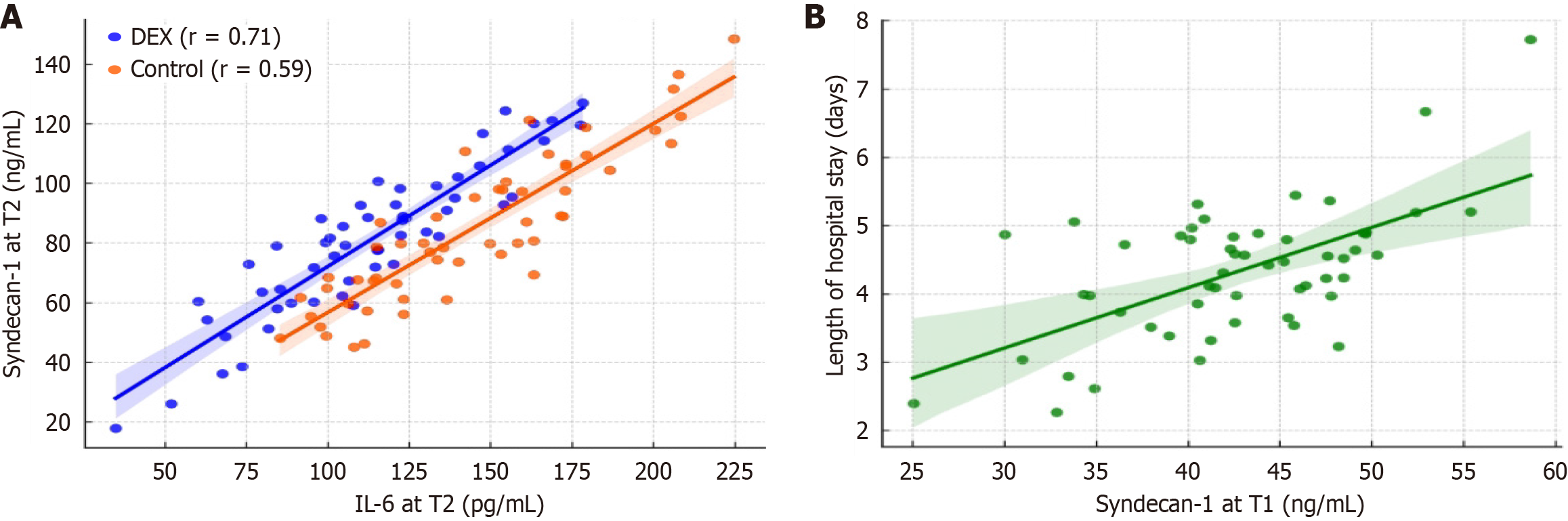

Heparan sulfate levels were also significantly reduced at T1 in the DEX group (12.19 ± 2.20 ng/mL vs 13.76 ± 2.44 ng/mL; P = 0.001). IL-6 levels at 24 hours postoperatively (T2) were significantly suppressed in the DEX group (110.77 ± 29.72 pg/mL vs 138.86 ± 35.95 pg/mL; P < 0.0001), with a strong positive correlation between IL-6 and syndecan-1 levels (r = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.55-0.82; P < 0.0001). TNF-α and CRP levels were also significantly lower. IL-10 and procalcitonin showed non-significant downward trends, while Ang-2 levels were significantly reduced in DEX-treated patients (P = 0.038). Baseline biomarker levels were comparable between groups (Table 2).

| Biomarker | Time point | DEX group (n = 55) | Control group (n = 55) | P value |

| Syndecan-1 (ng/mL) | T0 | 20.66 ± 4.43 | 20.85 ± 5.06 | 0.832 |

| T1 | 44.72 ± 7.10 | 48.73 ± 6.26 | 0.002 | |

| T2 | 34.16 ± 4.81 | 37.93 ± 5.78 | < 0.001 | |

| T3 | 29.21 ± 3.88 | 31.06 ± 3.47 | 0.009 | |

| Heparan sulfate (ng/mL) | T0 | 8.61 ± 1.71 | 8.70 ± 1.89 | 0.787 |

| T1 | 12.19 ± 2.20 | 13.76 ± 2.44 | 0.001 | |

| T2 | 9.97 ± 2.27 | 10.98 ± 2.31 | 0.023 | |

| T3 | 9.12 ± 2.82 | 9.29 ± 2.26 | 0.728 | |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | T0 | 85.92 ± 24.31 | 85.50 ± 29.06 | 0.934 |

| T1 | 117.68 ± 40.77 | 131.03 ± 41.68 | 0.092 | |

| T2 | 110.77 ± 29.72 | 138.86 ± 35.95 | < 0.0001 | |

| T3 | 97.19 ± 38.11 | 105.00 ± 42.71 | 0.314 | |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | T0 | 41.99 ± 9.72 | 40.30 ± 9.57 | 0.36 |

| T1 | 58.61 ± 11.35 | 61.52 ± 10.73 | 0.17 | |

| T2 | 56.90 ± 10.63 | 63.75 ± 12.17 | 0.002 | |

| T3 | 56.88 ± 11.32 | 60.36 ± 12.37 | 0.126 |

SDF imaging demonstrated that perioperative DEX administration significantly enhanced microcirculatory perfusion, as evidenced by improved PVD (21.40 ± 3.50 mm/mm2vs 19.94 ± 2.93 mm/mm2; P = 0.019) and mean flow index (2.83 ± 0.28 vs 2.66 ± 0.33; P = 0.005) at 24 hours postoperatively (T2) compared to controls. These microvascular improvements were accompanied by significantly lower central venous-to-arterial CO2 difference (3.89 ± 0.84 mmHg vs 4.63 ± 1.06 mmHg; P < 0.001) and reduced serum lactate levels (1.33 ± 0.40 mmol/L vs 1.65 ± 0.54 mmol/L; P = 0.003), indicating enhanced tissue oxygenation and more efficient microcirculatory flow. Temporal analysis revealed that while no baseline differences existed, these beneficial effects emerged distinctly at T2 before attenuating by T3, suggesting a time-dependent optimization of microvascular function with DEX administration (Table 3). The concordance between improved microcirculatory parameters and favorable metabolic markers underscores the potential of DEX to preserve perioperative microvascular integrity and tissue perfusion.

| Parameter | Time point | DEX group (n = 55) | Control group (n = 55) | P value |

| Perfused vessel density (mm/mm2) | T2 | 21.40 ± 3.50 | 19.94 ± 2.93 | 0.019 |

| Mean flow index | T2 | 2.83 ± 0.28 | 2.66 ± 0.33 | 0.005 |

| P(v-a)CO2 (mmHg) | T0 | 3.07 ± 0.78 | 3.27 ± 0.65 | 0.632 |

| T1 | 4.59 ± 0.86 | 4.94 ± 0.85 | 0.132 | |

| T2 | 3.89 ± 0.84 | 4.63 ± 1.06 | < 0.001 | |

| T3 | 4.00 ± 1.03 | 4.40 ± 0.87 | 0.128 | |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | T0 | 1.00 ± 0.32 | 1.09 ± 0.31 | 0.504 |

| T1 | 1.74 ± 0.37 | 1.82 ± 0.36 | 0.968 | |

| T2 | 1.33 ± 0.40 | 1.65 ± 0.54 | 0.003 | |

| T3 | 1.31 ± 0.58 | 1.51 ± 0.43 | 0.183 |

DEX administration was associated with significant improvements in recovery, including a 0.8-day reduction in length of hospital stay (P = 0.005), improved QoR-15 scores at 72 hours, and reduced overall 30-day complication rates (12.7% vs 30.9%; P = 0.036). The most affected complications were pneumonia and AKI, both of which were less frequent in the DEX group (Table 4). No differences were observed in readmission or mortality.

| Outcome measure | DEX group (n = 55) | Control group (n = 55) | Mean difference or OR (95%CI) | Absolute/relative effect | P value |

| Intraoperative fentanyl (μg) | 156.9 ± 31.6 | 175.5 ± 42.1 | -18.6 (-32.6 to -4.5) | - | 0 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 6.49 ± 1.29 | 7.29 ± 1.59 | -0.8 (-1.35 to -0.25) | - | 0.005 |

| QoR-15 score at 72 hours | 124.3 ± 9.2 | 118.7 ± 8.4 | 5.6 (2.3-9.0) | - | 0.001 |

| Postoperative infection | 4 (7.3) | 9 (16.4) | OR = 0.40 (0.11-1.37) | ARR 9.1%; RRR 55.5%; NNT approximately 11 | 0.135 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (3.6) | 6 (10.9) | OR = 0.30 (0.06-1.47) | ARR 7.3%; RRR 67.0%; NNT approximately 14 | 0.142 |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.3) | OR = 0.23 (0.02-2.12) | ARR 5.5%; RRR 75.3%; NNT approximately 18 | 0.195 |

| Ileus | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) | OR = 0.49 (0.04-5.53) | ARR 1.8%; RRR 50.0%; NNT approximately 56 | 0.564 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - | - |

| ICU admission | 4 (7.3) | 7 (12.7) | OR = 0.54 (0.14-2.04) | ARR 5.4%; RRR 42.5%; NNT approximately 19 | 0.358 |

| 30-day readmission | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) | OR = 1.00 (0.06-16.06) | - | > 0.05 |

| 30-day mortality | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | - | ARR 1.8%; RRR 100%; NNT approximately 56 | > 0.05 |

| Overall 30-day complications | 7 (12.7) | 17 (30.9) | 18.2% absolute risk reduction (3.1%-33.2%) | ARR 18.2%; RRR 58.9%; NNT approximately 6 | 0.036 |

The incidence of postoperative pneumonia, diagnosed according to CDC NHSN criteria based on clinical symptoms, elevated inflammatory markers, and new radiographic infiltrates, was lower in the DEX group [2/55 (3.6%)] than in the control group [6/55 (10.9%)]. All cases of AKI were stage 1 according to KDIGO staging, with no patients progressing to stage 2 or 3; the incidence was 1/55 (1.8%) in the DEX group and 4/55 (7.3%) in the control group. For key binary outcomes, absolute and relative effect sizes were calculated. DEX administration was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 18.2% (95%CI: 3.1%-33.2%) for overall 30-day complications, corresponding to a number needed to treat of 6.

Multivariable Logistic regression identified syndecan-1 > 45 ng/mL at T1 as an independent predictor of postoperative complications, with an OR of 2.88 (95%CI: 0.97-8.59, P = 0.057). Although the association approached statistical significance, the wide confidence interval reflects uncertainty likely due to sample size. Other covariates including age, surgical duration, and preoperative CRP levels were not independently associated with adverse outcomes (P > 0.05). The multivariable Logistic regression model yielded an Akaike information criterion of 120.74 and a Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 of 0.064, indicating modest explanatory power. While syndecan-1 > 45 ng/mL demonstrated a near-significant association with postoperative complications, the overall model explained approximately 6.4% of the variance in adverse outcomes (Table 5).

| Variable | Coef. | SE | z | P > |z| | OR (95%CI) |

| Const | -0.481 | 2.431 | -0.198 | 0.843 | 0.618 (0.005-72.488) |

| Syndecan_high | 1.059 | 0.557 | 1.902 | 0.057 | 2.884 (0.968-8.593) |

| Age | -0.009 | 0.029 | -0.305 | 0.76 | 0.991 (0.936-1.050) |

| Surgery_duration | -0.005 | 0.008 | -0.605 | 0.545 | 0.995 (0.979-1.011) |

| CRP | -0.006 | 0.081 | -0.075 | 0.94 | 0.994 (0.848-1.165) |

A significant time × group interaction was observed for IL-6 and syndecan-1 levels (both P < 0.001), indicating that DEX modified the postoperative inflammatory and endothelial injury trajectories. Cumulative AUC analysis revealed 25% and 19% reductions in IL-6 and syndecan-1 exposure, respectively, in the DEX group. At 24 hours postoperatively (T2), syndecan-1 positively correlated with IL-6 (DEX: r = 0.71; control: r = 0.59, Figure 2A), contrary to the initial summary statement, no statistically significant correlations were observed at individual timepoints. Specifically, the Pearson correlation coefficients were as follows: T0: R = -0.10, P = 0.476; T1: R = -0.02, P = 0.882; T2: R = -0.04, P = 0.796; T3: R =

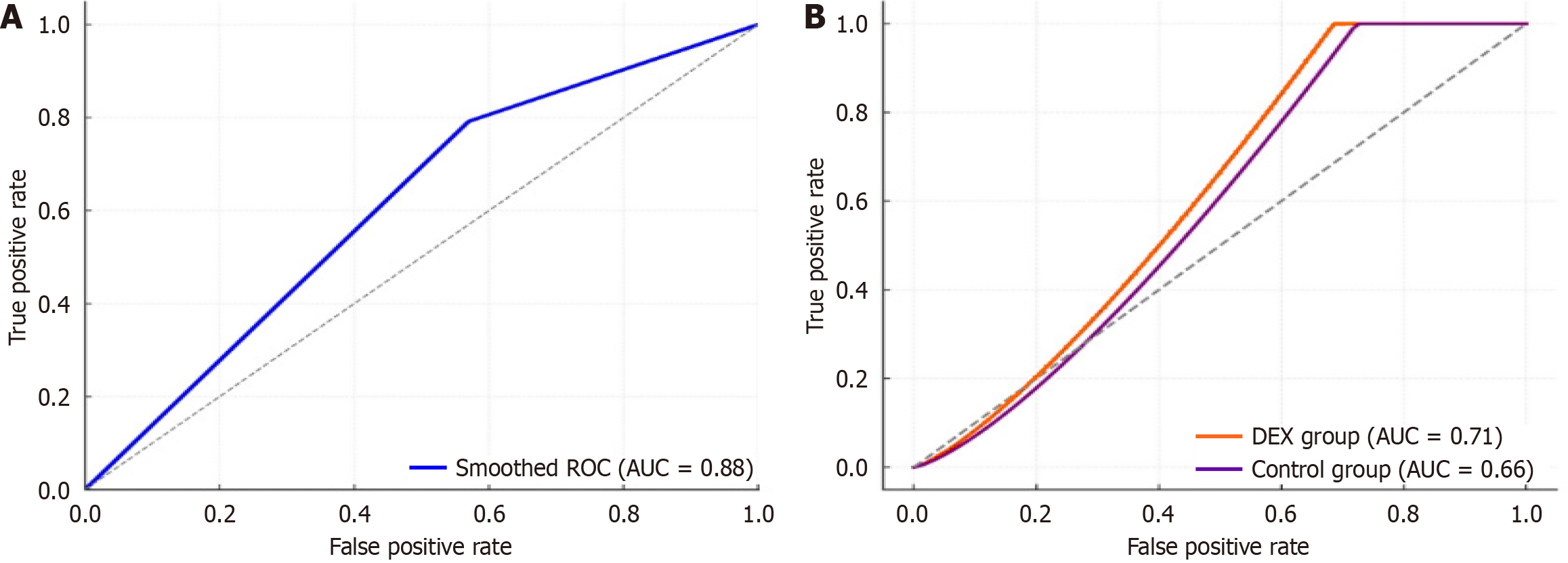

ROC analysis identified syndecan-1 > 45 ng/mL at abdominal closure as an optimal cut-off for predicting postoperative complications, with an AUC of 0.68 (95%CI: 0.59-0.76), sensitivity of 79.2%, and specificity of 43.0% (Figure 4A). Subgroup analyses revealed comparable discriminatory performance between groups. In the DEX arm, the ROC analysis yielded an AUC of 0.71 (95%CI: 0.60-0.82; sensitivity 77.8%, specificity 48.0%), while in the control arm, the AUC was 0.66 (95%CI: 0.55-0.77; sensitivity 80.0%, specificity 42.9%; Figure 4B).

The anti-inflammatory and endothelial-protective effects of DEX were preserved across subgroups. In patients aged > 65 years, the IL-6 reduction at T2 was even more pronounced (mean difference: -35.7 pg/mL; P = 0.001). In laparoscopic surgery patients, syndecan-1 levels were lower overall, but the relative benefit of DEX remained significant (P = 0.014 for interaction). No interaction was found by tumor type (gastric vs colorectal; Figure 5).

EG disruption has emerged as a pivotal mechanism underlying postoperative organ dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and impaired recovery, particularly following major abdominal oncologic surgery. The synergistic effects of surgical trauma and malignancy-associated cytokine release create a profound inflammatory surge that potentiates glycocalyx degradation, resulting in microvascular dysfunction and increased capillary permeability[12]. While DEX, a selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist with demonstrated endothelial-protective and anti-inflammatory properties, has shown efficacy in preclinical models, robust clinical evidence in surgical oncology populations remains scarce.

Our randomized controlled trial provides compelling evidence that DEX administration significantly preserves glycocalyx integrity, as quantified by an 8.2% reduction in syndecan-1 and an 11.4% decrease in heparan sulfate levels at abdominal closure. Importantly, syndecan-1 is a structural glycocalyx component, and even modest increases in its plasma concentration reflect substantial microvascular damage, as its release is non-linear and threshold-sensitive.

By contrast, IL-6 is a rapidly amplified soluble cytokine, and its large fluctuations over time reflect systemic inflammation rather than direct vascular injury. The strong correlation observed between syndecan-1 and IL-6 (r = 0.71, P < 0.0001) suggests that even small elevations in syndecan-1 are biologically meaningful and may contribute to downstream inflammatory cascades. Furthermore, syndecan-1 at T1 independently predicted prolonged length of stay (β = 0.101, P < 0.0001), reinforcing its clinical relevance as a biomarker of perioperative vascular injury and recovery burden.

These biochemical findings correlate with the pathophysiological model proposed by Becker et al[10], wherein syndecan-1 shedding directly reflects the magnitude of surgical stress response. The observed 20.2% attenuation of IL-6 and 10.7% reduction in TNF-α at 24 hours postoperatively demonstrate DEX's potent immunomodulatory effects, consistent with prior mechanistic studies in both surgical[9] and septic[12] settings.

The clinical translation of these molecular effects was particularly noteworthy. DEX-treated patients exhibited superior microcirculatory perfusion, improved tissue oxygenation, and reduced opioid requirements. These benefits culminated in a 0.8-day reduction in hospitalization and an 18.2% absolute risk reduction in 30-day complications, predominantly pneumonia and AKI - outcomes that compare favorably with established Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocols[13].

A critical advancement of our study is the identification of syndecan-1 > 45 ng/mL at closure as an independent pre

The present study confirms that perioperative DEX attenuates endothelial glycocalyx degradation in patients undergoing gastrointestinal tumor resection. At abdominal closure, DEX-treated patients exhibited significantly lower levels of syndecan-1 and heparan sulfate, key markers of glycocalyx shedding. These findings are consistent with the mechanistic understanding that DEX inhibits glycocalyx degradation via suppression of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress. Our finding that perioperative DEX significantly reduced syndecan-1 (-8.2%) and heparan sulfate

Preclinical studies provide additional insights into the potential mechanisms by which DEX may protect the endothelial glycocalyx. Experimental models have demonstrated that DEX attenuates systemic inflammation by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, while concomitantly enhancing anti-inflammatory mediators including IL-10. Its sympatholytic properties, mediated via α2-adrenergic receptor activation, reduce catecholamine-induced endothelial stress and oxidative injury. Furthermore, DEX has been shown to preserve endothelial barrier integrity by stabilizing adherens junction proteins (e.g., VE-cadherin) and limiting glycocalyx shedding of syndecan-1 and heparan sulfate. Collectively, these mechanistic pathways provide a biologically plausible rationale supporting the observed reductions in glycocalyx injury markers and improved microcirculatory profiles in the present study.

This study demonstrated that perioperative administration of DEX significantly attenuated endothelial glycocalyx degradation, reduced systemic inflammatory responses, and improved postoperative recovery outcomes in patients undergoing gastrointestinal tumor resection. Although the actual syndecan-1 concentrations at T1 were lower than those estimated during study planning, the observed inter-patient variability was substantially reduced. This improved precision allowed the study to maintain sufficient statistical power to detect significant between-group differences without the need for mid-study sample size recalculation. Adhering to ethical and registration guidelines, no unblinded interim analysis or adaptive design was implemented.

The discrepancy likely reflects differences in surgical modality (with a higher proportion of laparoscopic cases), timing of sample collection (immediately at closure rather than 30 minutes post-closure), and perioperative fluid and tempe

Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a single-center trial with a moderate sample size consisting predominantly of ASA II patients, the generalizability of our findings to more diverse surgical populations may be limited. Second, although we quantified circulating glycocalyx components, direct visualization of the endothelial glycocalyx—for instance, via intravital microscopy—was not performed, which could have provided additional mechanistic insight. Third, despite standardization of intraoperative ventilation parameters (tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure, plateau pressure), subtle interindividual variations during pneumoperitoneum may have influenced glycocalyx shedding. Future studies incorporating continuous respiratory mechanics monitoring and stricter lung-protective strategies may help clarify these effects. Fourth, although episodes of deep hypotension and vasopressor use were prospectively documented, these variables were not fully integrated into the current statistical model. Fifth, while perioperative fluid management was protocolized and balanced between groups, the study was not powered to discern subtle effects of fluid type (crystalloid vs colloid) or cumulative volume on glycocalyx integrity. Sixth, despite standardized patient positioning, minor variations in Trendelenburg angle or pneumoperitoneum pressure may have affected microcirculatory stress and glycocalyx injury. Future trials may benefit from continuous monitoring of intra-abdominal pressure and patient position to better control for these factors. Finally, it is important to recognize that glycocalyx integrity is influenced by a range of systemic factors—including renal, pulmonary, and cardiovascular function—as well as perioperative interventions such as ventilation, hemodynamic management, and fluid therapy. Thus, changes in biomarkers such as syndecan-1 and heparan sulfate likely reflect systemic glycocalyx dysfunction rather than injury specific to the gastrointestinal tract. Although we sought to minimize confounding through standardized management, the interpretation of our results should take this broader physiological context into account.

This study demonstrates that perioperative DEX is associated with reduced glycocalyx degradation, enhanced microcirculatory function, and accelerated recovery following gastrointestinal tumor surgery. Although the data show strong correlations between inflammation and glycocalyx injury, the study design precludes causal inference. Further investigation using time-series analysis, dose-response validation, and confounder-adjusted modeling is needed to determine whether DEX directly mitigates inflammation-induced endothelial damage. These findings nonetheless support the integration of DEX into ERAS pathways as an anti-inflammatory adjuvant and opioid-sparing agent. Syndecan-1 and related glycocalyx components may serve as dynamic biomarkers for perioperative risk stratification. Future research should focus on real-time glycocalyx monitoring and evaluate whether such interventions yield durable oncologic and functional benefits.

| 1. | Weinbaum S, Cancel LM, Fu BM, Tarbell JM. The Glycocalyx and Its Role in Vascular Physiology and Vascular Related Diseases. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2021;12:37-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MA, oude Egbrink MG. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:345-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in RCA: 1398] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van den Berg BM, Vink H, Spaan JA. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res. 2003;92:592-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tarbell JM, Cancel LM. The glycocalyx and its significance in human medicine. J Intern Med. 2016;280:97-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Whiteside TL. Exosome and mesenchymal stem cell cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:69-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dai X, Chen W, Qiao Y, Chen X, Chen Y, Zhang K, Zhang Q, Duan X, Li X, Zhao J, Tian F, Liu K, Dong Z, Lu J. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits the development of colorectal cancer by GSK-3β/TCF7/MMP9 pathway and synergies with capecitabine. Cancer Lett. 2024;582:216596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koide R, Hirane N, Kambe D, Yokoi Y, Otaki M, Nishimura SI. Antiadhesive nanosome elicits role of glycocalyx of tumor cell-derived exosomes in the organotropic cancer metastasis. Biomaterials. 2022;280:121314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fang FQ, Sun JH, Wu QL, Feng LY, Fan YX, Ye JX, Gao W, He GL, Wang WJ. Protective effect of sevoflurane on vascular endothelial glycocalyx in patients undergoing heart valve surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38:477-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miranda ML, Balarini MM, Bouskela E. Dexmedetomidine attenuates the microcirculatory derangements evoked by experimental sepsis. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:619-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Becker BF, Jacob M, Leipert S, Salmon AH, Chappell D. Degradation of the endothelial glycocalyx in clinical settings: searching for the sheddases. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80:389-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179-c184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 3715] [Article Influence: 265.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koch J, Idzerda NMA, Ettema EM, Kuipers J, Dam W, van den Born J, Franssen CFM. An acute rise of plasma Na(+) concentration associates with syndecan-1 shedding during hemodialysis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;319:F171-F177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Weerink MAS, Struys MMRF, Hannivoort LN, Barends CRM, Absalom AR, Colin P. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dexmedetomidine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:893-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 101.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zou Z, Li L, Schäfer N, Huang Q, Maegele M, Gu Z. Endothelial glycocalyx in traumatic brain injury associated coagulopathy: potential mechanisms and impact. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kobayashi A, Mimuro S, Katoh T, Kobayashi K, Sato T, Kien TS, Nakajima Y. Dexmedetomidine suppresses serum syndecan-1 elevation and improves survival in a rat hemorrhagic shock model. Exp Anim. 2022;71:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cho JS, Shim JK, Soh S, Kim MK, Kwak YL. Perioperative dexmedetomidine reduces the incidence and severity of acute kidney injury following valvular heart surgery. Kidney Int. 2016;89:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Taniguchi T, Kidani Y, Kanakura H, Takemoto Y, Yamamoto K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on mortality rate and inflammatory responses to endotoxin-induced shock in rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1322-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mohamed H, Hosny H, Tawadros Md P, Elayashy Md Desa Fcai M, El-Ashmawi Md H. Effect of Dexmedetomidine Infusion on Sublingual Microcirculation in Patients Undergoing On-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:334-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu Y, Zhao G, Zang X, Lu F, Liu P, Chen W. Effect of dexmedetomidine on opioid consumption and pain control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2021;16:491-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hirani R, Podder D, Stala O, Mohebpour R, Tiwari RK, Etienne M. Strategies to Reduce Hospital Length of Stay: Evidence and Challenges. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dong J, Lei Y, Wan Y, Dong P, Wang Y, Liu K, Zhang X. Enhanced recovery after surgery from 1997 to 2022: a bibliometric and visual analysis. Updates Surg. 2024;76:1131-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schmidt EP, Yang Y, Janssen WJ, Gandjeva A, Perez MJ, Barthel L, Zemans RL, Bowman JC, Koyanagi DE, Yunt ZX, Smith LP, Cheng SS, Overdier KH, Thompson KR, Geraci MW, Douglas IS, Pearse DB, Tuder RM. The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx regulates neutrophil adhesion and lung injury during experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2012;18:1217-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 672] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/