Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.111572

Revised: August 23, 2025

Accepted: October 13, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 2.9 Hours

Traditional postoperative nursing methods implemented after laparoscopic hepatectomy often leads to slow patient recovery. As a new nursing mode, en

To explore the influence of nursing under the ERAS concept on time to first ambulation and complications after laparoscopic hepatectomy.

Data from 119 patients, who underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy for various indications between January 2020 and March 2025, were divided into 2 groups according to nursing mode: Observation [nursing based on the ERAS concept (n = 59)], and control [basic nursing (n = 60)]. Time to first ambulation, complications, length of hospital stay, and numerical rating scale (NRS) scores were compared between the groups. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Findings indicated that after post-nursing intervention, the observation group experienced significantly sooner initial discharge times and shorter hospital stays than the control group (P < 0.05). The NRS score of the observation group was lower than that of the control group (P < 0.05). The observation group experienced a significantly lower incidence of postoperative complications than the control group (P < 0.05).

Operating room nursing based on the ERAS concept significantly shortens the time to first ambulation, reduces the incidence of postoperative complications, and improves patient quality of life after laparoscopic hepatectomy.

Core Tip: Nursing interventions based on the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) concept demonstrated significant advantages in laparoscopic hepatectomy, providing a scientific, systematic, and optimized nursing program for clinical practice. Its effectiveness in shortening hospital stay, reducing complications, and improving pain has broad promotional value. Operating room nursing based on the ERAS concept significantly shortens the time to first ambulation, reduces the incidence of postoperative complications, and improves patient quality of life after laparoscopic hepatectomy.

- Citation: Zhu XL, Zhang DY, Fu SN, Ji HT, Wang XB. Effects of nursing under the enhanced recovery after surgery concept on time to first ambulation after laparoscopic hepatectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(11): 111572

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i11/111572.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.111572

Laparoscopic hepatectomy has recently gained popularity in the field of liver surgery, with several advantages over conventional open surgery. Patients undergoing laparoscopic hepatectomy experience fewer complications after surgery, with less blood loss, and experience shorter hospital stays than those undergoing open hepatectomy[1,2]. Due to these advantages, laparoscopic surgery in older patients has also yielded favorable short-term effects[3]. In complex liver surgeries, such as central hepatectomy, the application of emerging laparoscopic technologies has gradually matured. Laparoscopic central hepatic resection can be performed safely and effectively using standardized surgical techniques and treatment of the hepatic vein roots[4]. In addition, laparoscopic technology has demonstrated good safety and feasibility for repeated hepatectomies in patients with relapsed liver cancer, especially by experienced surgical teams[5,6]. Laparoscopic hepatectomy can achieve oncological results comparable with open surgery in complex cases such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, provided the most suitable patients are chosen, and also helps to decrease post

Laparoscopic hepatectomy is a minimally invasive technique that offers quick recovery with fewer complications; however, effective postoperative care is vital. Research indicates that nursing strategies significantly affect postoperative recovery and quality of life. Early nutritional management is crucial for faster recovery and reduced hospital stay[8]. Furthermore, integrating improved rehabilitation care with mental health education can effectively enhance the postoperative psychological condition and quality of life of patients, and lower the risk for complications[9]. Second, effective postoperative pain management is crucial in nursing. Although laparoscopic surgery typically causes mild pain due to minimal trauma, it is essential to encourage early patient activity and recovery[10]. This research indicated that patients experienced a notable decrease in pain scores a few hours after laparoscopic hepatectomy, aiding in the swift recovery of activity and function[11]. Preventing and managing postoperative complications are crucial in nursing care. Although complications after laparoscopic hepatectomy are rare, vigilant monitoring and a prompt response to issues, such as bleeding or gallbladder leakage, are essential[12,13]. Implementing an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) regimen can further decrease the occurrence of postoperative complications[14,15]. Postoperative psychological support and health education are vital aspects of nursing care in Japan. By implementing psychological interventions and health education, patient anxiety and depression can be significantly alleviated, thereby enhancing quality of life after surgery[16]. Evidence suggests that providing mental health education after surgery can markedly improve patient psychological condition and life contentment[17].

The present study explored the impact of operating room nursing performed under the ERAS concept on first-time to ambulation and complications after laparoscopic hepatectomy to provide a basis for clinical nursing practice in efforts to improve postoperative recovery and quality of life.

This retrospective cohort study included 119 patients who underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy at the Shaoxing University Affiliated Hospital between January 2020 and March 2025 for various indications including hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 70), hepatic hemangioma (n = 30), and hepatic cyst (n = 19). Patients were divided into 2 groups according to nursing model: Observation [operating room nursing based on the ERAS concept (n = 59)]; Control [basic operating room nursing (n = 60)]. General demographic information was collected from all patients.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy at the authors’ hospital; (2) Age > 18 years; (3) Child classification of preoperative liver function grade A to B; and (4) Complete clinical data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Severe visceral dysfunction; (2) Combined mental and cognitive impairment; (3) Combined coagulation dysfunction; and (4) Incomplete medical records or lost data.

The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of Shaoxing University Affiliated Hospital (No. 2025-114-01). Given the retrospective nature of the study and the use of anonymized patient data, requirements for informed consent were waived.

Basic operating room nursing measures were used for the control group. Before the procedure, the attending physician and head nurse of the department conducted basic health education, including surgical procedures, precautions for preoperative fasting and water ban, and postoperative precautions to help patients eliminate fear and relieve anxiety. Patients wore surgical gowns on the day of surgery and received basic psychological counseling. Strict sterilization and verification of drugs and surgical instruments before surgery were performed to ensure safety. During the operation, nursing staff closely monitored vital signs and maintained a sterile environment in the surgical area. After the procedure, the focus was placed on inspecting patient status, timely treatment of wound drainage, observation of vital signs, and prevention of common complications such as infection and bleeding.

Based on the ERAS concept, a systematic and multi-link nursing process was formulated and combined with multiple optimization measures, including the following.

Preoperative health education and psychological counseling: After the patient understands the surgical plan, the nursing team is led by the head nurse in the operating room to organize a special education and communication meeting. Detailed explanation of the procedure, advantages of laparoscopic surgery, and benefits of ERAS concepts are used for enhancing patient understanding and cooperation. Preparation measures were emphasized on the day of the operation, including preoperative fasting (water ban 8 hours before the operation, fasting for 12 hours), reasonable dietary regulation, and avoidance of long-term fasting and insufficient hydration. These measures help patients relieve their anxiety and build a positive mindset by explaining possible stress responses and intraoperative stress response mechanisms.

Multimodal analgesia protocol: A standardized regimen was used combining preemptive analgesia, regional techniques, and non-opioid agents. Preoperatively, patients received oral celecoxib 400 mg and acetaminophen 1000 mg. Intraoperatively, a transversus abdominis plane block was performed using 0.25% ropivacaine 20 mL per side. Postoperatively, patients were administered intravenous parecoxib 40 mg every 12 hours for 24 hours, followed by oral celecoxib 200 mg twice daily. Patient-controlled analgesia with sufentanil (background infusion 2 μg/hour, bolus 2 μg, lockout time 10 minutes) was available as rescue medication. Pain was assessed every 4 hours using the numerical rating scale (NRS); if NRS ≥ 4, an additional 50 mg tramadol was administered intravenously. The goal was to maintain NRS ≤ 3 throughout hospitalization.

Intraoperative nursing: In addition to standardized sterilization measures, the focus is placed on keeping the operating room environment warm and avoiding physiological stress responses caused by low temperatures. Rational control of fluid input prevents edema and increased burden on the heart. Patients’ vital signs are continuously monitored to ensure that all indicators meet the surgical requirements.

Early ambulation activities and rehabilitation measures: After drug efficacy evaluation and vital signs are stable, patients are encouraged to get up early and move. Usually, the nurse assists with ambulation within 6 hours after the operation and gradually increases the amount of activity. Specific measures to prevent pulmonary complications and deep venous thrombosis include assisting patients with coughing, sputum collection, balloon blowing, abdominal breathing training, and ankle pump exercises. In addition, patients are guided to perform simple physical rehabilitation maneuvers, such as sitting, standing, and walking, laying the foundation for postoperative improvement of intestinal function and promotion of rehabilitation.

Continuous monitoring and individualized management: Implementing dynamic monitoring, combining pain scores, nutritional support, and psychological status, and adjusting nursing plans in a timely manner. The nursing team regularly evaluates patient recovery to ensure the implementation of various ERAS measures.

Postoperative recovery: Record the first time to ambulation and length of hospitalization.

Postoperative complications: The overall incidence of postoperative complications in the 2 groups was determined, including incision infection, digestive tract discomfort, urinary tract infection, and lower-limb venous thrombosis. Pain level was assessed using a NRS[18]. The NRS is an 11-point scale scored from 0 to 10, in which 0 indicates “no pain” and 10 represents “the worst possible pain”. Patients indicated the corresponding score based on their maximum pain experience over the previous week. The NRS is widely recognized to be valid and reliable.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and were compared between groups using independent t-tests to assess statistically significant differences in the mean. Categorical variables are expressed as count and corresponding percentage [n (%)] and compared using the χ2 test for group comparison. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

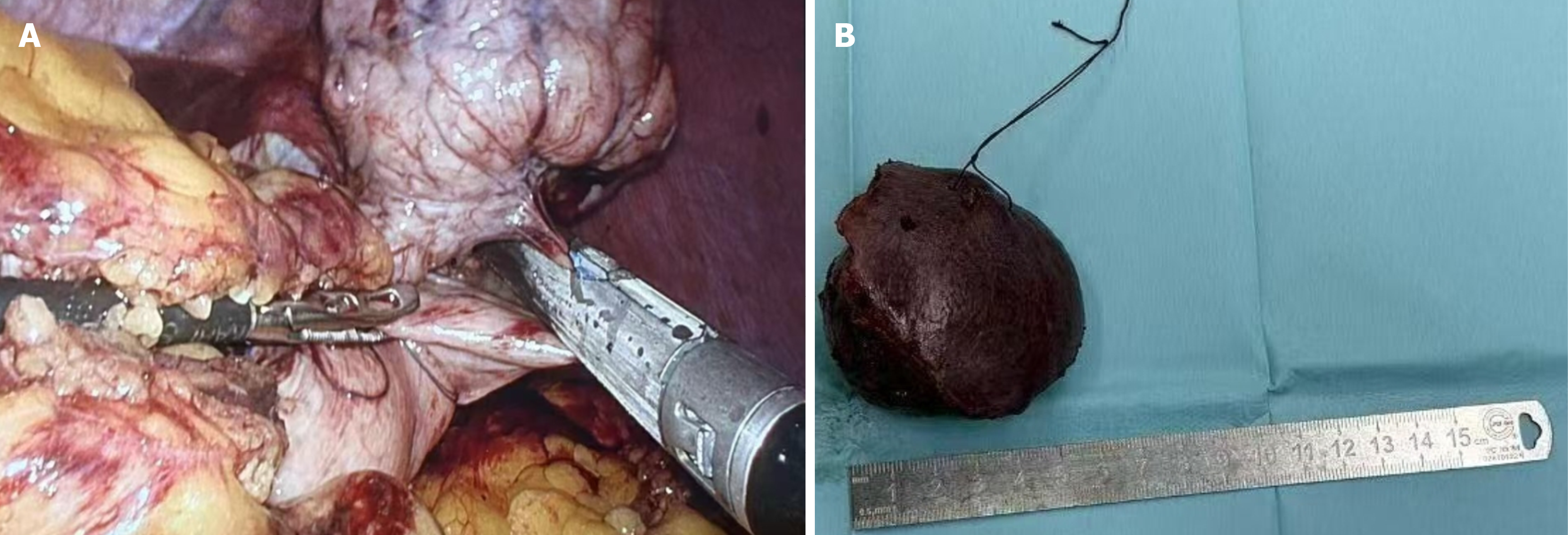

Among the 60 patients in the observation group, males accounted for 50.8%, with a mean (± SD) age of 55.0 ± 10.0 years, with 12 (20.34%) with hypertension and 9 (15.25%) with diabetes. In the control group, males accounted for 46.7%, with mean age of 56.0 ± 11.0 years, with 13 (21.67%) with hypertension and 8 (13.33%) with diabetes. Additional information regarding the 2 groups is summarized in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Representative intraoperative images are presented in Figure 1.

| Index | Observation group (n = 59) | Control group (n = 60) | P value |

| Age, years | 55.0 ± 10.0 | 56.0 ± 11.0 | 0.379 |

| Gender, male | 30 (50.8) | 28 (46.7) | 0.514 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.23 ± 3.05 | 21.26 ± 3.24 | 0.735 |

| ASA status | 0.732 | ||

| I | 24 (40.68) | 25 (41.67) | |

| II | 21 (35.59) | 20 (33.33) | |

| III | 14 (23.73) | 15 (25.00) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 12 (20.34) | 13 (21.67) | 0.174 |

| Diabetes | 9 (15.25) | 8 (13.33) | 0.235 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.4 ± 1.4 | 0.746 |

| Smoking history | 0.182 | ||

| Yes | 18 (30.51) | 18 (30.0) | |

| No | 41 (69.49) | 42 (70.0) | |

| Drinking history | 0.196 | ||

| Yes | 21 (35.59) | 23 (38.33) | |

| No | 38 (64.41) | 37 (61.67) |

After the nursing intervention, the length of hospital stay of patients in the observation group was significantly shorter than that in the control group (P < 0.05), and the time to first ambulation of those in the in the observation group was significantly shorter than that in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Index | Control group (n = 60) | Observation group (n = 59) |

| Length of stay (day) | 12.65 ± 5.16 | 7.02 ± 1.54 |

| First out of bed time (hour) | 38.76 ± 4.71 | 21.83 ± 2.43 |

After the nursing intervention, the incidence of postoperative complications in the observation group was 3.33% (2/59), which was significantly lower than that in the control group (10/60) (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Group | Control group (n = 60) | Observation group (n = 59) | P value |

| Surgical site infection | 3 (5.08) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal discomfort | 2 (3.39) | 1 (1.67) | |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (5.08) | 1 (1.67) | |

| Lower limb venous thrombosis | 2 (3.39) | 0 (0) | |

| Total incidents | 10 (16.95) | 2 (3.33) |

Before nursing, the mean pain scores of the observation and control groups were 6.48 ± 1.25 and 6.57 ± 1.03, respectively (P > 0.05). However, after nursing, the mean pain score in the observation group (2.64 ± 0.8) was statistically lower than that of the control group (4.73 ± 0.91) (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Group | Control group (n = 60) | Observation group (n = 59) | P value |

| Before nursing | 6.57 ± 1.03 | 6.48 ± 1.25 | < 0.001 |

| After nursing | 4.73 ± 0.91 | 2.64 ± 0.89 |

As a minimally invasive surgical procedure, laparoscopic hepatectomy has significant advantages, such as less trauma and quicker recovery than traditional open surgery[19]. However, some patients continue to experience adverse psychological reactions, such as anxiety and tension before the operation, and these emotional states may negatively affect postoperative rehabilitation[20]. The literature points out that effective nursing interventions can significantly reduce patients’ physiological and psychological stress responses and promote postoperative recovery[21]. Therefore, it is important to explore various nursing programs for patients undergoing laparoscopic hepatectomy. Accordingly, the present study aimed to propose an optimized nursing strategy to provide new concepts for improving prognosis in clinical practice. ERAS-based nursing interventions reduce postoperative stress and accelerate recovery. This investigation compared postoperative recovery, complications, pain scores, and nursing satisfaction between observation and control groups. The results indicated that the observation group had shorter hospital stay, earlier mobility, fewer complications, better pain management, and higher nursing satisfaction, thereby offering valuable clinical insights.

According to our results, patients in the observation group experienced a significantly reduced hospital stay compared with those in the control group (7.02 ± 1.54 days vs 12.65 ± 5.16 days; P < 0.05), which is consistent with findings reported in other studies[22]. Shortening hospital stay not only helps reduce the use medical resources but also reduces the risk for cross-infection, improves medical efficiency, and is consistent with developments in modern surgical care. The results of this study revealed that the time to first ambulation was significantly advanced (21.83 ± 2.43 hours vs 38.76 ± 4.71 hours; P < 0.05). Research has confirmed the effectiveness of evidence-based nursing interventions in promoting early mobilization, which enhances pulmonary function recovery, gastrointestinal rehabilitation, and overall postoperative recovery. As a crucial component of ERAS care, early mobilization significantly improves patients’ recovery outcomes, reduces complication rates, and boosts their quality of life and satisfaction[22]. For instance, a study on early endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal tumors demonstrated that ERAS patients showed marked improvements in postoperative complication management and prognosis, shorter hospital stays, and higher patient satisfaction. This is consistent with previous research results because early activity can effectively reduce thrombosis, pulmonary complications, and delayed rehabilitation of intestinal function.

In terms of postoperative complications, the incidence rate in the observation group (3.33%) was significantly lower than that in the control group (16.95%) (P < 0.001), especially in terms of surgical site infections, gastrointestinal discomfort, urinary system infections, and deep venous thrombosis in the lower limbs. According to a retrospective cohort study involving elderly patients, the ERAS program significantly reduced hospital stay and decreased the severity of postoperative complications[23], fully demonstrating that ERAS care plays a positive role in slowing postoperative body stress, maintaining homeostasis, and improving immunity. Therefore, preventing complications not only improves patient prognosis but also reduces subsequent treatment burden and economic pressure. The mean NRS score of the observation group was significantly lower than that of the control group after receiving care (2.64 ± 0.89 vs 4.73 ± 0.91; P < 0.001), reflecting the advantages of strengthening pain assessment and effective interventions under the ERAS concept. Good pain control helped improve patient coordination, reduced postoperative discomfort and stress responses, and promoted earlier recovery. This is consistent with the results of previous studies[24]. Effective pain control not only enhances patient comfort but also accelerates recovery by suppressing inflammation. Research indicates that inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α play pivotal roles in inflammatory processes, with their levels being modulated through targeted pain management strategies[25]. Therefore, future research should integrate continuous monitoring of physiological biomarkers, such as inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α), to better understand and optimize the impact of analgesic strategies on gastrointestinal function and inflammatory responses. This approach will facilitate the development of more personalized and effective treatment plans, thereby accelerating patient recovery and improving their quality of life.

Although the present study adopted a retrospective cohort design and combined multiple objective indicators to verify the positive role of nursing interventions based on the ERAS concept in laparoscopic hepatectomy, there were some limitations. First, this was a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, which may have affected the generalization and statistical power of the results. Larger-sample multicenter studies should be conducted to enhance the representativeness and reliability of our conclusions. Second, the selection of patients was biased, and the inclusion criteria may limit the scope of the study. For example, patients with poor liver function (Child grade C) were not included, which limits the applicability of our conclusions. In addition, nursing interventions have some subjectivity and operational differences and, even if all are implemented by experienced caregivers, individual differences may affect the objective evaluation of the intervention effects. Third, the research mainly focused on short-term postoperative recovery indicators and lacked a systematic assessment of patient long-term rehabilitation effects, such as quality of life, liver function recovery, and recurrence within 6 months or a year after surgery. This information is of great significance for a comprehensive evaluation of the clinical value of ERAS nursing programs. Finally, because this study adopted a retrospective design, there was an inevitable possibility of information omission or incomplete data records, which may have affected the accuracy of the analysis. Differences in underlying diseases may influence postoperative recovery profiles, such as ambulation capacity and liver function reserve. Unfortunately, due to the constraints of the retrospective design, we were unable to perform further subgroup adjustments or control for disease-related confounding factors, which may affect the accuracy of the outcome interpretation. Therefore, future research should systematically evaluate the effectiveness of ERAS nursing programs in different clinical environments and patient groups through prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trials, and further verify their clinical promotion value and safety to guide more scientific and individualized nursing practice.

In summary, nursing interventions based on the ERAS concept demonstrated significant advantages in laparoscopic hepatectomy, providing a scientific, systematic, and optimized nursing program for clinical practice. Its effectiveness in shortening hospital stay, reducing complications, and improving pain has broad promotional value. In the future, nursing measures should be continuously optimized in combination with different types of surgery and individual differences in patients and further promote the in-depth implementation of the ERAS concept in the field of surgery, providing strong guarantees for improving patient rehabilitation results and nursing quality.

| 1. | Abdul Halim N, Xiao L, Cai J, Sa Cunha A, Salloum C, Pittau G, Ciacio O, Azoulay D, Vibert E, Cai X, Cherqui D. Repeat laparoscopic liver resection after an initial open hepatectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2024;26:1364-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen YC, Soong RS, Chiang PH, Chai SW, Chien CY. Reappraisal of safety and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic repeat hepatectomy in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: it is feasible for the pioneer surgical team. BMC Surg. 2024;24:373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chua DW, Sim D, Syn N, Abdul Latiff JB, Lim KI, Sim YE, Abdullah HR, Lee SY, Chan CY, Goh BKP. Impact of introduction of an enhanced recovery protocol on the outcomes of laparoscopic liver resections: A propensity-score matched study. Surgery. 2022;171:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Combari-Ancellin P, Nakada S, Savier É, Golse N, Faron M, Lim C, Vibert É, Cherqui D, Scatton O, Goumard C. Initial laparoscopic liver resection is associated with reduced adhesions and transfusions at the time of salvage liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford). 2024;26:1190-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Groot N, Fariñas F, Cabrera-Gómez CG, Pallares FJ, Ramis G. Weaning causes a prolonged but transient change in immune gene expression in the intestine of piglets. J Anim Sci. 2021;99:skab065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Griffiths CD, Xu K, Wang J, McKechnie T, Gafni A, Parpia S, Ruo L, Serrano PE. Laparoscopic hepatectomy is safe and effective for the management of patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases in a population-based analysis in Ontario, Canada. A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020;83:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hildebrand N, Verkoulen K, Dewulf M, Heise D, Ulmer F, Coolsen M. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy in the elderly patient: systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2021;23:984-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiang W, Mao Q, Xie Y, Ying H, Xu H, Ge H, Feng L, Liu H, Li J, Liang X. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic hepatectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9:4563-4572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kobayashi K, Kawaguchi Y, Schneider M, Piazza G, Labgaa I, Joliat GR, Melloul E, Uldry E, Demartines N, Halkic N. Probability of Postoperative Complication after Liver Resection: Stratification of Patient Factors,Operative Complexity, and Use of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233:357-368.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koh YX, Zhao Y, Tan IE, Tan HL, Chua DW, Tan EK, Teo JY, Ang KA, Au MKH, Goh BKP. Cost-Effectiveness of Laparoscopic vs Open Liver Resection: A Propensity Score-Matched Single-Center Analysis of 920 Cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2025;241:203-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kokudo T, Takemura N, Inagaki F, Yoshizaki Y, Mihara F, Edamoto Y, Yamada K, Kokudo N. Laparoscopic minor liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2023;53:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kuai J, Liu Y, Ding W, Wang Y. Study on the application of perioperative nutrition management in accelerated rehabilitation surgery in patients with laparoscopic primary liver cancer resection. Minerva Surg. 2024;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li DX, Ye W, Yang YL, Zhang L, Qian XJ, Jiang PH. Enhanced recovery nursing and mental health education on postoperative recovery and mental health of laparoscopic liver resection. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:1728-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li LQ, Jiao Y. Risk and management of adverse events in minimally invasive esophagectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;17:103941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liang X, Ying H, Wang H, Xu H, Liu M, Zhou H, Ge H, Jiang W, Feng L, Liu H, Zhang Y, Mao Z, Li J, Shen B, Liang Y, Cai X. Enhanced recovery care versus traditional care after laparoscopic liver resections: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2746-2757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liao C, Lai X, Zhong J, Zeng W, Zhang J, Deng W, Shu J, Zhong H, Cai L, Liao R. Reducing the length of hospital stay for patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty by application of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway: a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30:385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ni X, Jia D, Chen Y, Wang L, Suo J. Is the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Program Effective and Safe in Laparoscopic Colorectal Cancer Surgery? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:1502-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pinto F, Pangrazio MD, Martinino A, Todeschini L, Toti F, Cristin L, Caimano M, Mattia A, Bianco G, Spoletini G, Giovinazzo F. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis: an umbrella review. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1340430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rajalingam R, Rammohan A, Cherukuru R, Rela M. Minimally Invasive Liver Transplantation: The Recipient Operation. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2025;15:102532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rotellar F, Martí-Cruchaga P, Zozaya G, Tuero C, Luján J, Benito A, Hidalgo F, López-Olaondo L, Pardo F. Standardized laparoscopic central hepatectomy based on hilar caudal view and root approach of the right hepatic vein. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2020;27:E7-E8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shen Y, Xi Y, Ru LGX, Liu H. The impact of ERAS-based nursing interventions on postoperative complication management and prognosis in early gastrointestinal tumor endoscopic resection: a prospective randomized controlled study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2025;410:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Timmer MA, Veenhof C, de Kleijn P, de Bie RA, Schutgens REG, Pisters MF. Movement behaviour patterns in adults with haemophilia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020;11:2040620719896959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yan C, Li BH, Sun XT, Yu DC. Laparoscopic hepatectomy is superior to open procedures for hepatic hemangioma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2021;20:142-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhou X, Zhou X, Cao J, Hu J, Topatana W, Li S, Juengpanich S, Lu Z, Zhang B, Feng X, Shen J, Chen M. Enhanced Recovery Care vs. Traditional Care in Laparoscopic Hepatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:850844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ziogas IA, Esagian SM, Giannis D, Hayat MH, Kosmidis D, Matsuoka LK, Montenovo MI, Tsoulfas G, Geller DA, Alexopoulos SP. Laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: An individual patient data survival meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2021;222:731-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/