Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.108188

Revised: July 24, 2025

Accepted: September 9, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 3.5 Hours

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the primary method for treating cholecystitis. Traditional postoperative care has poor outcomes for patient recovery. The en

To evaluate the effects of ERAS on postoperative gastrointestinal recovery and quality of life in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

This is a retrospective study design in which we collected clinical data from 120 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy at our hospital. Patients were divided into a control group (n = 60) and a study group (n = 60) based on the type of nursing intervention. The control group received conventional care, while the study group received ERAS. We assessed gastrointestinal recovery, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction before and after the nursing interventions in both groups.

After nursing care, the gastrointestinal recovery times (time to bowel sounds return, time to flatus, time to first bowel movement, and time to first meal) in the study group were significantly shorter than those in the control group, with statistically significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.05). Additionally, the quality of life in the study group was significantly higher than that in the control group (P < 0.05). The nursing satisfaction in the study group was also significantly higher than that in the control group, with statistically significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.05).

In summary, compared to conventional nursing, ERAS can more rapidly promote gastrointestinal recovery and improve the quality of life in patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Further clinical application of this approach is warranted.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the primary method for treating cholecystitis. Traditional postoperative care has poor outcomes for patient recovery. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) on postoperative gastrointestinal recovery and quality of life in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Compared to conventional nursing, ERAS can more rapidly promote gastrointestinal recovery and improve the quality of life in patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. By improving gastrointestinal recovery, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction, while reducing pain, ERAS provides valuable insights for modern surgical care.

- Citation: Sun ZY, Ye L, Mao YY, Liang L. Effect of enhanced recovery after surgery nursing on gastrointestinal recovery function and life quality in patients laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(11): 108188

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i11/108188.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i11.108188

Acute cholecystitis is among the most common gastrointestinal conditions encountered in medical practice, which is an inflammation of the gallbladder due to blockage and bacterial infection of the cystic duct, with over 90% of cases linked to gallstones or cholelithiasis[1,2]. Patients typically present with symptoms such as severe biliary colic, abdominal distension, nausea, and vomiting[3]. Without timely and appropriate intervention, acute cholecystitis may become complicated due to hidden symptoms and delayed diagnosis, potentially advancing to gangrenous cholecystitis and perforation, resulting in peritonitis[4]. Studies indicate that each year, about 2%-4% of gallbladder stone disease patients exhibit symptoms, with yearly incidence rates for acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, and obstructive jaundice being 0.3%-0.4%[5]. Without proper and prompt treatment, acute cholecystitis and cholangitis in adults can lead to fatal outcomes[5].

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is currently the primary method for treating acute calculous cholecystitis, mainly due to its minimally invasive nature, reduced postoperative pain, and faster recovery time compared to traditional open surgery[6-8]. In recent years, despite continuous improvements in surgical techniques, effective postoperative nursing models still play a crucial role in patient recovery and overall surgical outcomes. Postoperative care is crucial for recovery after surgery, yet conventional care models tend to emphasize the disease and complications after surgery rather than physical recuperation[9,10]. These traditional nursing approaches often overlook the importance of early mobilization, nutritional support, and proactive pain management, which may be detrimental to the patient’s natural healing process.

Lately, there has been increasing interest in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), which involves a multidisciplinary team working together to speed up recovery during perioperative care[11]. ERAS includes a comprehensive set of evidence-based interventions, including preoperative patient education and counseling, optimization of anesthesia and analgesia protocols, early postoperative mobilization and feeding, meticulous fluid management, and attention to psychological support[12,13]. The implementation of ERAS protocols has achieved significant success in a wide range of surgical procedures, resulting in significant reductions in hospital stay, fewer postoperative complications, improved patient satisfaction, and substantial cost savings for healthcare systems[14]. Studies have shown that implementing the ERAS protocol may not only hasten the return of hip joint function and self-care abilities but also alleviate anxiety and boost quality of life[15,16]. The program has been put into place to enhance care before, during, and after surgery to speed up recovery[17]. Furthermore, the ERAS program has markedly improved the speed of functional recovery and lessened the necessity for extensive care after surgical procedures[18].

While the benefits of ERAS care models have been widely applied in elective surgery, they are less commonly used in patients with acute cholecystitis. Patients with acute cholecystitis often experience more severe inflammation, pain, and physiological disturbances. The presence of acute inflammation can impair gastrointestinal motility, increase the risk of postoperative ileus, and exacerbate pain. Therefore, studying the application effect of ERAS care models in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy is of great significance. In summary, this study aims to evaluate the impact of enhanced recovery care protocols on gastrointestinal recovery and quality of life in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with the aim of providing valuable insights into the effectiveness of enhanced recovery care in optimizing postoperative recovery for patients with acute cholecystitis.

This is a retrospective study design. We collected clinical data from a total of 120 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy at our hospital. Data collection spanned from January 2023 to December 2024. Based on the type of care received, patients were divided into two groups: The study group received ERAS care (n = 60), and the control group received conventional care interventions (n = 60). Clinical information was collected for both groups.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Clinically diagnosed with acute cholecystitis[19]; (2) No contraindications to general anesthesia and laparoscopic surgery; (3) No history of mental illness; and (4) Complete medical records and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with severe visceral dysfunction; (2) Patients with coagulation disorders, gastrointestinal dysfunction, or immune or metabolic abnormalities that may affect surgical procedures and outcomes; (3) Patients with systemic infections, gallbladder perforation, or necrosis; (4) Patients with malignant tumors or other acute abdominal conditions; (5) Patients with a history of abdominal surgery; (6) Pregnant or breastfeeding women; and (7) Patients with incomplete medical records or missing data.

The control group received conventional care methods. The control group was provided with a conventional care model. Patients were informed in advance about the role and necessity of surgical treatment for the disease, and were instructed on surgery-related precautions and cooperation matters. One day before the operation, the surgical procedure, expected effects, and possible postoperative complications were explained to the patient and their family to prepare them psychologically, and psychological counseling was conducted to reduce their mental stress. Vital signs were monitored during the operation. Postoperatively, analgesic interventions were administered, and the recovery of gastrointestinal function was observed.

The study group adopted an ERAS protocol: (1) Health education: Nursing staff showed patients surgical models and simulated the surgical process by playing surgical videos to help them understand the surgical procedures. Health education leaflets were distributed to patients, detailing the surgical process and prognosis. Questions from patients were actively answered, and the importance of rapid recovery surgical nursing was explained, guiding patients to actively cooperate; (2) Psychological nursing: Nursing staff proactively communicated with patients, paying attention to their emotional changes and guiding them to express their true feelings. Nursing staff expressed understanding and respect to enhance patient trust. Language skills were used to guide patients, instructing them to appropriately vent emotions through various channels and adjust their psychological state. Listening to light music, such as classical music, folk music, and piano music, helped patients forget worries and maintain physical and mental relaxation. Shifting attention through activities such as playing chess, reading, singing, and dancing reduced psychological stress and burden. Talking with relatives and friends helped express emotions and maintain a good psychological state. Psychological nursing was implemented throughout the perioperative period. When patients were awake after surgery, they were promptly encouraged and comforted to further enhance their confidence in recovery; (3) Gastrointestinal preparation: The day before surgery, a semi-liquid diet was maintained for dinner, such as millet porridge and soft noodles. Eight hours before surgery, 500 mL of warm 10% glucose injection was taken orally. Two hours before surgery, 250 mL of warm glucose injection was taken orally to complete bowel cleansing and prepare the gastrointestinal tract; (4) Warming care: Before surgery, nursing staff adjusted the operating room temperature and humidity to a comfortable state and pre-warmed the operating table. During the patient’s surgery, all intravenous fluids and irrigation solutions used were pre-warmed, and other parts of the patient’s body were effectively covered to reduce exposure and prevent hypothermia; (5) Early ambulation: After surgery, patients were returned to the ward after anesthesia recovery. The patient’s feelings were asked, and they were assisted to maintain a comfortable position to improve their comfort. Patients were instructed to perform limb exercises in bed. Four to six hours after surgery, if the patient had no discomfort, they could get out of bed to urinate and turn over appropriately in bed. Bed sheets were kept flat to prevent pressure ulcers. Twenty-four hours after surgery, patients were guided to perform simple activities at the bedside according to their tolerance, with nursing staff or family members accompanying them to avoid falls. Forty-eight hours after surgery, patients could perform simple activities in the corridor with family accompaniment, controlling the amount of activity to avoid overexertion; (6) Pain management: After surgery, analgesics were appropriately selected according to the patient’s pain level, as prescribed by the doctor, to help reduce pain. Patient’s family members were instructed to chat with the patient and divert attention through watching TV, playing games, and other methods to relieve pain. If the patient’s irritability and anxiety were severe, a pain pump could be used as prescribed by the doctor to avoid pain-induced stress reactions; (7) Environmental care: Nursing staff maintained gentle movements, prepared clean and tidy bed sheets and bedding for patients, effectively adjusted indoor lighting, maintained fresh indoor air, and provided a good environment for patients to rest. A “quiet please” sign was hung on the door to maintain indoor quiet and ensure patients had sufficient rest; and (8) Dietary care: If the patient had no abnormalities after surgery, they could drink a small amount of millet porridge or sugar water 6 hours after surgery, maintaining a liquid diet; two days after surgery, a semi-liquid diet was maintained, gradually transitioning to a normal diet. A diet high in vitamins and protein was maintained, with appropriate increases in fresh fruits and vegetables, mainly a light diet, to prevent constipation.

Gastrointestinal recovery: This will be measured by monitoring the return of bowel sounds, passage of flatus and stool, time to first oral intake, and length of hospital stay. Quality of life[20]: The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire will assess quality of life across four domains: Physical, psychological, social, and environmental. Each domain is scored out of 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Pain assessment[21]: Pain levels will be evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS) at baseline, postoperative days 1, 3, and 5. The VAS ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain), with detailed descriptors for mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-10) pain levels. Nursing satisfaction: A custom questionnaire will assess patient satisfaction with nursing care, with scores indicating “dissatisfaction” (below 60), “basic satisfaction” (60-85), or “very satisfied” (above 85). The overall satisfaction rate will be calculated as the percentage of patients reporting “basic satisfaction” or “very satisfied”.

Data will be analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables will be presented as mean ± SD and compared between groups using independent t-tests. Categorical variables will be presented as n (%) and analyzed using χ2 tests. The WHOQOL-BREF domain scores will be calculated according to the official scoring manual, with each domain transformed to a 0-100 scale. Statistical significance will be defined as P < 0.05.

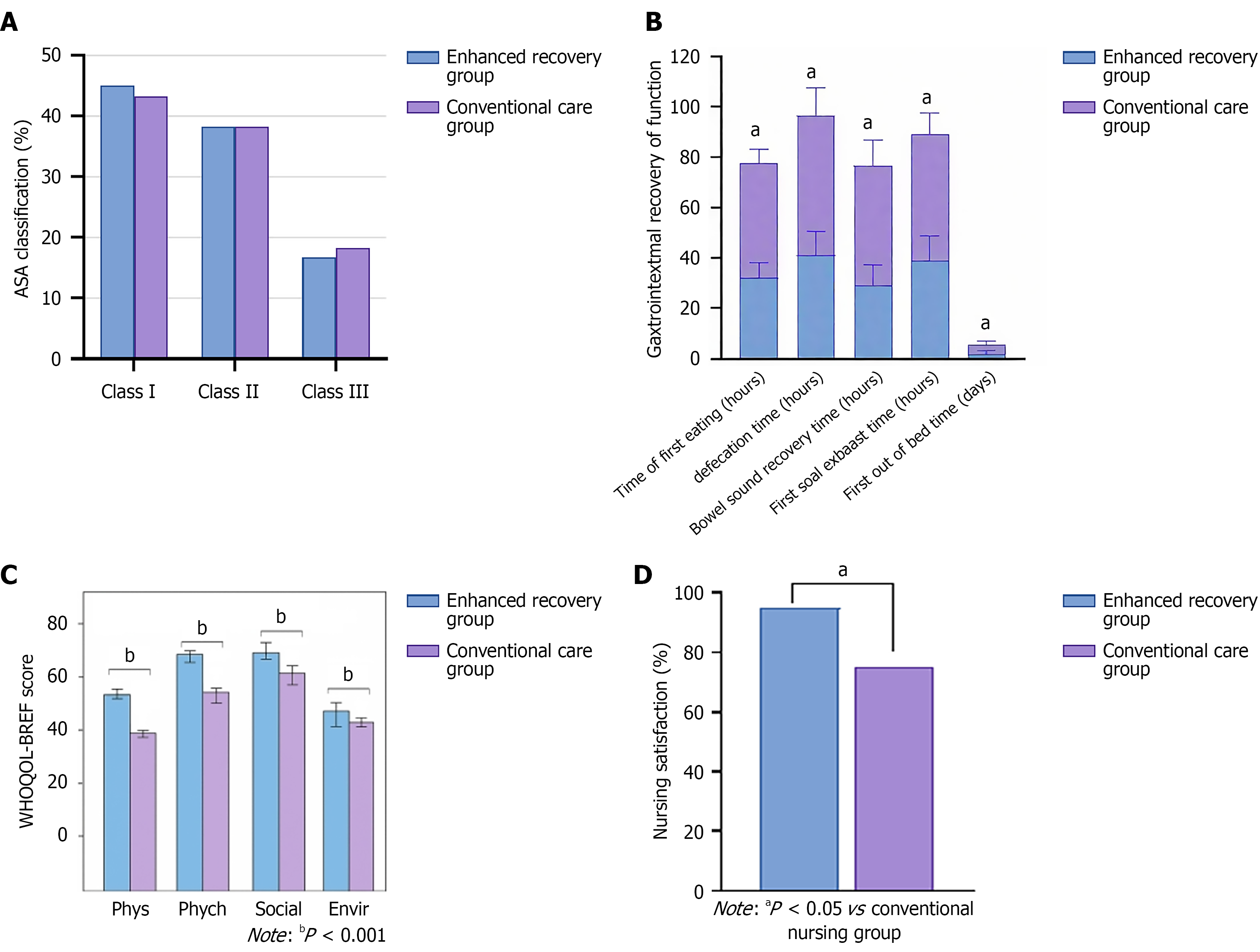

There were no statistically significant differences in general data between the two groups of patients (P > 0.05). The mean age in the ERAS group was 53.0 ± 9.0 years, and in the conventional care group, it was 54.0 ± 9.5 years (P = 0.452). In the ERAS group, males accounted for 48.3% (29 patients) and females 51.7% (31 patients), while in the conventional care group, males accounted for 45.0% (27 patients) and females 55.0% (33 patients; P = 0.714). In the ERAS group, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I accounted for 45.0% (27 patients), class II for 38.3% (23 patients), and class III for 16.67% (10 patients), while in the conventional care group, ASA class I accounted for 43.3% (26 patients), class II for 38.3% (23 patients), and class III for 18.33% (11 patients; P = 0.967). In summary, the two groups of patients were comparable in these general data (Table 1). The distribution of ASA grades is shown in Figure 1A.

| Indicator | Enhanced recovery group (n = 60) | Conventional care group (n = 60) | P value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 53.0 ± 9.0 | 54.0 ± 9.5 | 0.452 |

| Gender | 0.714 | ||

| Male | 29 (48.3) | 27 (45.0) | |

| Female | 31 (51.7) | 33 (55.0) | |

| ASA classification | 0.967 | ||

| Class I | 27 (45.0) | 26 (43.3) | |

| Class II | 23 (38.3) | 23 (38.3) | |

| Class III | 10 (16.67) | 11 (18.33) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 24 (40.0) | 20 (33.3) | 0.449 |

| Diabetes | 6 (10.0) | 11 (18.3) | 0.191 |

| Smoking history | 0.637 | ||

| Yes | 12 (20.0) | 10 (16.7) | |

| No | 48 (80.0) | 50 (83.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 7 (11.7) | 7 (11.7) | |

| No | 53 (88.3) | 53 (88.3) | |

| History of abdominal surgery | 16 (26.7) | 17 (28.3) | 0.838 |

| Preoperative antibiotics | 10 (16.7) | 9 (15) | 0.803 |

After nursing intervention, the ERAS group had significantly shorter times for bowel sound recovery (28.87 ± 8.50 hours), time to first flatus (39.15 ± 9.46 hours), time to first defecation (41.15 ± 9.46 hours), and time to first feeding (32.15 ± 6.06 hours) compared to the conventional care group, which were (47.70 ± 10.20 hours), (49.90 ± 8.55 hours), (55.38 ± 11.05 hours), and (45.38 ± 5.68 hours), respectively (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the time to first ambulation after surgery in the ERAS group (2.15 ± 1.00 days) was also significantly shorter than in the conventional care group (3.27 ± 1.75 days), with statistical significance (P < 0.05; Figure 1B).

The results showed that after nursing intervention, the ERAS group scored significantly higher than the conventional care group in all dimensions of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire (P < 0.001). The mean WHOQOL-BREF physical score for the ERAS group was 56.35 ± 5.07, significantly higher than the 40.02 ± 3.61 for the conventional care group (P < 0.001). The mean WHOQOL-BREF psychological score for the ERAS group was 70.75 ± 5.33, also significantly higher than the 59.13 ± 6.44 for the conventional care group (P < 0.001). This indicates that the ERAS group experienced better emotions, cognitive function, and self-esteem. The mean WHOQOL-BREF social score for the ERAS group was 77.22 ± 6.30, also significantly higher than the 62.55 ± 5.73 for the conventional care group (P < 0.001). The mean WHOQOL-BREF environment score for the ERAS group was 48.75 ± 6.31, significantly higher than the 41.92 ± 4.93 for the conventional care group (P < 0.001; Table 2, Figure 1C).

| Indicator | Enhanced recovery group (n = 60) | Conventional care group (n = 60) | P value |

| WHOQOL-BREF physical | 56.35 ± 5.07 | 40.02 ± 3.61 | < 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-BREF psychological | 70.75 ± 5.33 | 59.13 ± 6.44 | < 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-BREF social | 77.22 ± 6.30 | 62.55 ± 5.73 | < 0.001 |

| WHOQOL-BREF environment | 48.75 ± 6.31 | 41.92 ± 4.93 | < 0.001 |

Before nursing intervention, there was no significant difference in preoperative pain scores between the ERAS group and the conventional care group (P = 0.936), and the scores of the two groups were basically the same (7.58 ± 1.22 vs 7.57 ± 1.03). On postoperative days 1, 3, and 5, the pain scores of the ERAS group were significantly lower than those of the conventional care group (P < 0.001; Table 3).

| Indicator | Enhanced recovery group (n = 60) | Conventional care group (n = 60) | P value |

| Before surgery | 7.58 ± 1.22 | 7.57 ± 1.03 | 0.936 |

| 1 day after surgery | 4.58 ± 0.87 | 5.57 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| 3 days after surgery | 2.37 ± 0.48 | 4.62 ± 0.52 | < 0.001 |

| 5 days after surgery | 1.98 ± 0.29 | 3.90 ± 0.30 | < 0.001 |

After nursing intervention, there was a statistically significant difference in nursing satisfaction between the ERAS group and the conventional care group (P < 0.05), with nursing satisfaction rates of 95.0% (57/60) and 75.0% (45/60), respectively (Figure 1D).

The ERAS nursing model, validated through empirical evidence, significantly improves postoperative recovery and clinical outcomes via evidence-based medicine. Its successful adoption in laparoscopic surgeries across departments shows that ERAS protocols improve gastrointestinal recovery, and shorten recovery times[22]. Laparoscopic myo

Compared to conventional care, ERAS nursing significantly shortened recovery times for gastrointestinal function, passage of flatus, first bowel movement, and first feeding (P < 0.05). ERAS also facilitated earlier ambulation, reduced hospital stays (P < 0.05), and decreased pain scores on postoperative days 3 and 5 (P < 0.05). Supporting previous finding, this study demonstrates ERAS nursing’s effectiveness in promoting intestinal recovery, shortening hospital stays, and accelerating patient recovery[25].

ERAS nursing also significantly improves quality of life. Higher WHOQOL-BREF scores in the ERAS group across all four domains (P < 0.001) demonstrate its positive impact on both physical recovery and mental well-being. The improvement in the environmental domain indicates better adaptation to hospital settings and enhanced comfort during recovery. Environmental care measures (such as quiet management of the ward, air circulation, and adequate lighting) can reduce postoperative anxiety and sleep interruption, thereby indirectly improving gastrointestinal motility and pain perception, which may explain the association between the environmental domain and overall recovery speed observed in this study. Validated in studies of radical gastrectomy (improved gastrointestinal function, fewer complications), ERAS nursing accelerates physical recovery and enhances overall quality of life[26]. With a significantly higher satisfaction rate (95.0% vs 75.0%, P < 0.05), the ERAS group’s positive feedback underscores the effectiveness of ERAS nursing and overall patient satisfaction. This is basically consistent with previous research results.

This single-center retrospective study has limitations. The small sample size of 120 patients may limit the generalizability and reliability of the results. To ensure broader applicability, these findings should be validated in a larger po

In conclusion, ERAS nursing offers more effective postoperative support for laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients with acute calculous cholecystitis. By improving gastrointestinal recovery, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction, while reducing pain, ERAS provides valuable insights for modern surgical care.

| 1. | Mencarini L, Vestito A, Zagari RM, Montagnani M. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Cholecystitis: A Comprehensive Narrative Review for a Practical Approach. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gallaher JR, Charles A. Acute Cholecystitis: A Review. JAMA. 2022;327:965-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Costanzo ML, D'Andrea V, Lauro A, Bellini MI. Acute Cholecystitis from Biliary Lithiasis: Diagnosis, Management and Treatment. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12:482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Auda A, Al Abdullah R, Khalid MO, Alrasheed WY, Alsulaiman SA, Almulhem FT, Almaideni MF, Alhikan A. Acute Cholecystitis Presenting With Septic Shock as the First Presentation in an Elderly Patient. Cureus. 2022;14:e20981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SO, Yim SK. [Management of Acute Cholecystitis]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2018;71:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park JH, Jin DR, Kim DJ. Change in quality of life between primary laparoscopic cholecystectomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy after percutaneous transhepatic gall bladder drainage. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e28794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oji K, Otowa Y, Yamazaki Y, Arai K, Mii Y, Kakinoki K, Nakamura T, Kuroda D. Taking antithrombic therapy during emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis does not affect the postoperative outcomes: a propensity score matched study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee JH, Kim G. The First Additional Port During Single-Incision Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2020;24:e2020.00024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhu Q, Yang J, Zhang Y, Ni X, Wang P. Early mobilization intervention for patient rehabilitation after renal transplantation. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:7300-7305. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Peng Y, Wan H, Hu X, Xiong F, Cao Y. Internet+Continuous Nursing Mode in Home Nursing of Patients with T-Tube after Hepatolithiasis Surgery. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:9490483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deng H, Li B, Qin X. Early versus delay oral feeding for patients after upper gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ali S, Latif T, Sheikh MA, Shafiq MB, Zahra DE, Abu Bakar M. Review of Perioperative Care Pathway for Children With Renal Tumors. Cureus. 2022;14:e24928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Peden CJ, Aggarwal G, Aitken RJ, Anderson ID, Bang Foss N, Cooper Z, Dhesi JK, French WB, Grant MC, Hammarqvist F, Hare SP, Havens JM, Holena DN, Hübner M, Kim JS, Lees NP, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN, Mohseni S, Ordoñez CA, Quiney N, Urman RD, Wick E, Wu CL, Young-Fadok T, Scott M. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Emergency Laparotomy Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations: Part 1-Preoperative: Diagnosis, Rapid Assessment and Optimization. World J Surg. 2021;45:1272-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Van Schie P, Van Bodegom-Vos L, Van Steenbergen LN, Nelissen RGHH, Marang-van de Mheen PJ; IQ JOINT STUDY GROUP. A more comprehensive evaluation of quality of care after total hip and knee arthroplasty: combining 4 indicators in an ordered composite outcome. Acta Orthop. 2022;93:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Morse KW, Heinz NK, Abolade JM, Wright-Chisem J, Alice Russell L, Zhang M, Mirza S, Pearce-Fisher D, Orange DE, Figgie MP, Sculco PK, Goodman SM. Factors Associated With Increasing Length of Stay for Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty and Total Knee Arthroplasty. HSS J. 2022;18:196-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Woerden V, Lodewick TM, Bemelmans MHA, Olde Damink SWM, Dejong CHC, van Dam RM. Abandoning Prophylactic Abdominal Drainage after Hepatic Surgery: 10 Years of No-Drain Policy in an Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Environment. Dig Surg. 2017;34:411-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Molenaar CJ, van Rooijen SJ, Fokkenrood HJ, Roumen RM, Janssen L, Slooter GD. Prehabilitation versus no prehabilitation to improve functional capacity, reduce postoperative complications and improve quality of life in colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Wakabayashi G, Kozaka K, Endo I, Deziel DJ, Miura F, Okamoto K, Hwang TL, Huang WS, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Noguchi Y, Shikata S, Ukai T, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Mori Y, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Jagannath P, Jonas E, Liau KH, Dervenis C, Gouma DJ, Cherqui D, Belli G, Garden OJ, Giménez ME, de Santibañes E, Suzuki K, Umezawa A, Supe AN, Pitt HA, Singh H, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Teoh AYB, Honda G, Sugioka A, Asai K, Gomi H, Itoi T, Kiriyama S, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Matsumura N, Tokumura H, Kitano S, Hirata K, Inui K, Sumiyama Y, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:41-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 769] [Cited by in RCA: 789] [Article Influence: 98.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Digestive System Disease Professional Committee of Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine. [Consensus on Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment of Cholecystitis (2025)]. Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2025;33:351-370. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Roulin D, Demartines N. Principles of enhanced recovery in gastrointestinal surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:2619-2627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun YM, Wang Y, Mao YX, Wang W. The Safety and Feasibility of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery in Patients Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:7401276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cao Q, Li P, Yang X, Qian J, Wang Z, Lu Q, Gu M. Laparoscopic radical cystectomy with pelvic re-peritonealization: the technique and initial clinical outcomes. BMC Urol. 2018;18:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li G, Zhang J, Cai J, Yu Z, Xia Q, Ding W. Enhanced recovery after surgery in patients undergoing laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pędziwiatr M, Mavrikis J, Witowski J, Adamos A, Major P, Nowakowski M, Budzyński A. Current status of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in gastrointestinal surgery. Med Oncol. 2018;35:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, Rockall TA, Young-Fadok TM, Hill AG, Soop M, de Boer HD, Urman RD, Chang GJ, Fichera A, Kessler H, Grass F, Whang EE, Fawcett WJ, Carli F, Lobo DN, Rollins KE, Balfour A, Baldini G, Riedel B, Ljungqvist O. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019;43: 659-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1071] [Cited by in RCA: 1392] [Article Influence: 198.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dong F, Li Y, Jin W, Qiu Z. Effect of ERAS pathway nursing on postoperative rehabilitation of patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery: a meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2025;25:239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/