Published online Jul 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2351

Revised: May 19, 2024

Accepted: June 18, 2024

Published online: July 27, 2024

Processing time: 99 Days and 8.2 Hours

Extragastric lesions are typically not misdiagnosed as gastric submucosal tumor (SMT). However, we encountered two rare cases where extrinsic lesions were misdiagnosed as gastric SMTs.

We describe two cases of gastric SMT-like protrusions initially misdiagnosed as gastric SMTs by the abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Based on the CT and EUS findings, the patients underwent gastroscopy; however, no tumor was identified after incising the gastric wall. Subsequent surgical exploration revealed no gastric lesions in both patients, but a mass was found in the left triangular ligament of the liver. The patients underwent laparoscopic tumor resection, and the postoperative diagnosis was hepatic hemangiomas.

During EUS procedures, scanning across different layers and at varying degrees of gastric cavity distension, coupled with meticulous image analysis, has the potential to mitigate the likelihood of such misdiagnoses.

Core Tip: We report two cases of gastric submucosal tumor-like protrusions initially misdiagnosed as gastric submucosal tumors based on contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasound findings. However, they were ultimately diagnosed as hepatic hemangiomas. We hope that our findings will contribute to avoiding such misdiagnoses in future clinical practice.

- Citation: Wang JJ, Zhang FM, Chen W, Zhu HT, Gui NL, Li AQ, Chen HT. Misdiagnosis of hemangioma of left triangular ligament of the liver as gastric submucosal stromal tumor: Two case reports. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(7): 2351-2357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i7/2351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i7.2351

With the development of economic status and increased awareness of personal health, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is becoming increasingly prevalent, and submucosal tumor (SMT)-like protrusions in the stomach are often discovered during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastric SMT-like protrusions are categorized into true intramural tumor-like lesions, which are gastric SMT, and pseudo-extramural compression-type lesions. Extramural compression of the stomach may present symptoms and endoscopic findings similar to those of gastric SMT. Currently, it is believed that endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and computed tomography (CT) can accurately differentiate extramural compression from true SMT, with EUS generally considered superior to CT in achieving a more precise distinction[1]. However, in specific circumstances, misdiagnosis can still occur even when both EUS and CT are used. Here, we report two cases of hepatic hemangiomad that were initially misdiagnosed as SMT. These patients underwent various diagnostic modalities, including endoscopic examination, EUS, and contrast-enhanced abdominal CT.

Case 1: A 45-year-old male patient presented with a history of recurrent pain and discomfort in the epigastric region for > 10 years.

Case 2: A 62-year-old male patient presented with recurrent heartburn and acid regurgitation for > 1 year.

Case 1: Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT performed at another hospital revealed a gastric mass. Subsequent gastroscopy at our hospital revealed a shallow protrusion in the fornix of the gastric fundus. On linear EUS, the gastric fornix region revealed a normally layered structure of the gastric wall. A closely adherent oval-shaped area with medium echogenicity was observed externally, exhibiting uniform internal echogenicity. The dimensions of some sections were approximately 2.2 cm × 1.1 cm. Contrast-enhanced CT of the stomach revealed a round soft tissue lesion in the gastric fundus, measuring approximately 2.4 cm × 1.7 cm. The lesion demonstrated uniform density, smooth borders, and protrusion into the gastric lumen. The outer margin of the gastric wall appeared smooth. Mild enhancement of the lesion was observed on the contrast-enhanced scan, suggestive of a gastric stromal tumor.

Case 2: Gastroscopy performed at a local hospital revealed erosive gastritis, reflux esophagitis, and multiple SMTs in the gastric fundus. The patient underwent contrast-enhanced full abdominal CT at our hospital, which revealed a small, nearly round lesion in the gastric fundus, measuring approximately 1.9 cm × 1.7 cm. There was no significant enhancement in the post-contrast images, with gastric leiomyoma or neurogenic tumor being the primary considerations.

Both patients had unremarkable history of past illness.

Both patients had no notable personal and family history.

Physical examinations revealed no significant positive findings in both patients.

Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, biochemistry, tumor markers, etc., showed no significant positive results in both patients.

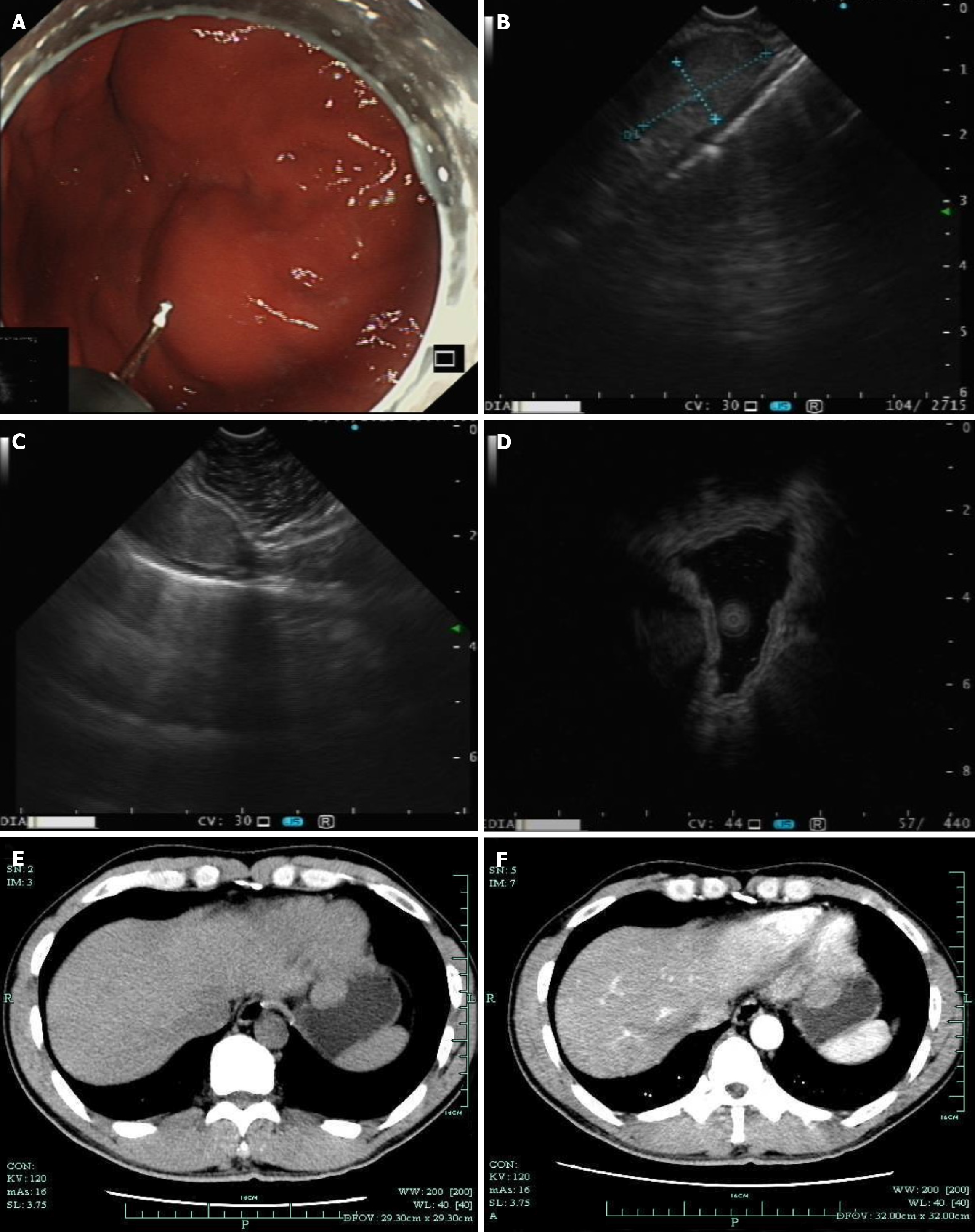

Case 1: During white-light gastroscopy, a submucosal mass of approximately 2 cm was visible at the gastric fundus, covered by the normal gastric mucosal epithelium (Figure 1A). Under linear EUS, the lesion appeared as a hypoechoic mass, suspected to originate from the muscularis propria layer (Figure 1B). However, on the left side of the image, a complete 5-layer structure of the gastric wall was visible (Figure 1C). Miniprobe sonography (MPS) scanning of the lesion revealed a hypoechoic mass suspected to originate from the muscularis propria layer (Figure 1D). During the CT non-contrast phase, a protruding mass into the gastric lumen was visible (Figure 1E), and during the CT contrast-enhanced phase, the lesion showed uniform mild enhancement (Figure 1F).

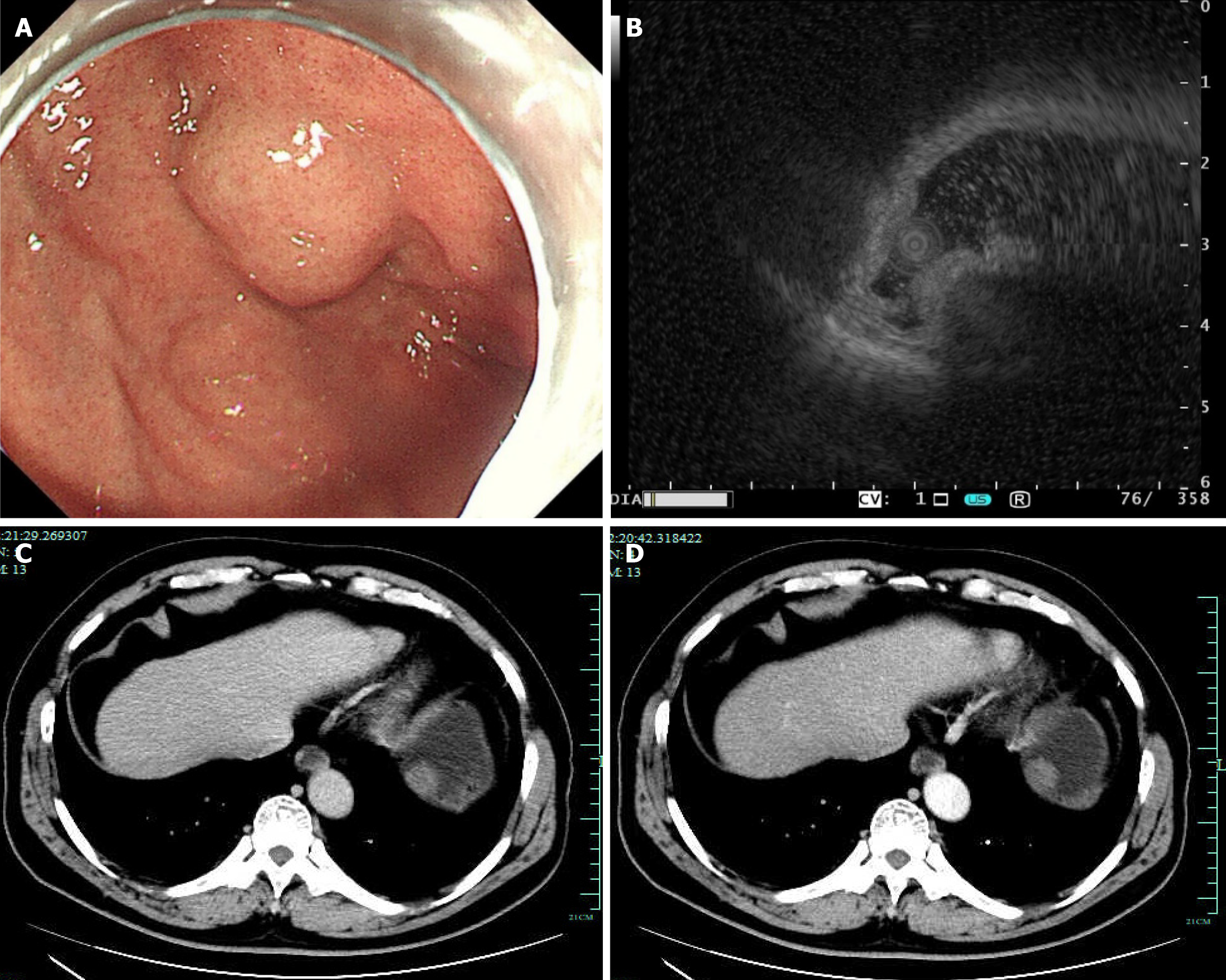

Case 2: During white-light gastroscopy, a submucosal mass of approximately 2 cm was found at the gastric fundus, covered by the normal gastric mucosal epithelium (Figure 2A). Scanning the lesion using MPS revealed a hypoechoic mass suspected to originate from the muscularis propria layer (Figure 2B). CT demonstrated an intraluminal mass within the stomach that appeared as a non-prominently enhancing protrusion, in both the non-contrast phase (Figure 2C) and contrast-enhanced phase (Figure 2D).

Both patients were ultimately diagnosed with a hemangioma of the left triangular ligament of the liver.

Both patients underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection, but since the lesions could not be found during the procedure, they were both referred for surgical treatment.

Both patients underwent laparoscopic surgery, during which the lesions were excised. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, with no significant complications or sequelae.

Incidental findings of luminal protrusions with intact mucosa are inadvertently encountered during gastroenteroscopy. Such findings can be attributed to subepithelial intramural lesions or extramural compression exerted by adjacent structures[2]. The documented prevalence of such lesions during routine endoscopic examinations is approximately 0.36%[3]. With the advancement of noninvasive diagnostic techniques, including abdominal US, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging, attempts have been made to differentiate subepithelial lesions from extramural compression. A preliminary investigation evaluating the diagnostic efficacy of EUS in 19 patients with extragastric compression revealed 100% accuracy in distinguishing extragastric compression from SMTs. EUS outperformed alternative modalities such as US and CT in terms of diagnostic capability[1]. A prior investigation assessed the efficacy of EUS in identifying submucosal lesions in a cohort of 150 patients. One hundred and two patients presented with intramural lesions, while 48 exhibited extraluminal compression. The diagnostic performance of endoscopy in discriminating between submucosal lesions and extraluminal compression yielded a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 29%. In comparison, EUS demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy[4], with a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 100% in distinguishing between the conditions. A study examined 238 patients with gastric SMTs or extragastric compression to assess the diagnostic utility of EUS. After excluding 183 patients with SMTs, the remaining 55 patients with extragastric compression were analyzed. There were 32 cases involving normal extragastric organs (10 spleen, 6 splenic blood vessels, 9 gallbladder, 3 liver, 3 pancreas, and 1 small intestine); 12 cases of benign pathological lesions (7 liver cysts, 2 hepatic hemangiomas, and 1 each of splenic cyst, pancreatic cyst, and pancreatic cystadenoma); and 5 cases of malignant tumors (1 liver cancer, 2 liver metastasis from colon cancer, 1 pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma, and 1 splenic lymphoma). The remaining 6 EUS examinations did not reveal any SMT or extragastric compression, suggesting transient external pressure. In cases where upper endoscopy indicates extragastric compression resembling an SMT, EUS serves as a valuable tool to elucidate the underlying cause of the extragastric compression[5]. Based on the evidence from these studies and our clinical expertise, EUS is presently considered the most effective modality for differentiating between gastric extramural compression and SMTs. However, despite its efficacy, there are instances where extramural compression near the gastric fundus wall, caused by mass compression within the left triangular ligament area of the liver, may still be misdiagnosed as SMT. The misdiagnosis can be attributed to the anatomical proximity of the left triangular ligament of the liver, which is a peritoneal ligament consisting of anterior and posterior layers located between the upper left lobe of the liver and the diaphragm. The left triangular ligament attaches to the upper surface of the left lobe of the liver and divides the left suprahepatic space into anterior and posterior compartments. Each left triangular ligament has a long free border that extends from the lateral end of the left lobe of the liver to the diaphragm. Notably, the left triangular ligament of the liver is situated in close proximity to the cardioesophageal junction. Upon gastric insufflation, the space-occupying lesions within the area of the hepatic triangular ligament can readily protrude into the gastric cavity, so the sites mistaken for SMT are also concentrated at the cardiac fundus. The diaphragm and omentum that enveloped the mass were mistakenly interpreted as a high-echo serosal layer on EUS. When scanning the gastric fundus using MPS, the insertion direction of the MPS cannot be parallel to the lesion, making it difficult to align the ultrasound scan direction perpendicular to the gastric wall of the lesion. Moreover, adjusting the depth of insertion of the microprobe does not allow for comprehensive scanning of the entire lesion, making it challenging to obtain complete ultrasound information. Similar to the first case, in an outpatient setting, when using linear EUS for scanning, the scan direction is perpendicular to the gastric wall of the lesion, enabling visualization of the genuine gastric wall layer structure. Therefore, when scanning gastric fundus lesions, linear EUS can be used to reduce the anatomical structure distortion caused by ultrasound scan angle issues. Additionally, careful analysis of ultrasound images is necessary. Upon close examination of one of the EUS images of the lesion, one can observe a complete 5-layer structure of the gastric wall at the edge of the image, while the high echo of the diaphragm in the center of the image can be misleading, leading to misdiagnosis. Therefore, when analyzing gastric fundus lesions, attention should be paid to whether the observed image accurately represents the anatomical location. Vigilant analysis of the EUS images is required. In conclusion, when using EUS to scan gastric fundus and cardiac lesions, a more meticulous analysis of the images is needed. If linear EUS is available, it should be used to obtain a more accurate anatomical structure. If only MPS is available, thorough water insufflation is required, and multiple scans of the lesion from different angles should be performed to gather more EUS information.

Hepatic hemangiomas, also known as hepatic cavernous hemangiomas, are the most prevalent benign hepatic neoplasms. They consist of dysplastic vascular channels within the liver parenchyma. They exhibit a slow growth pattern and a protracted disease course. The patient demonstrates unremarkable hepatic function. However, rapid enlargement of the lesion may elicit clinical discomfort[6]. If the tumor diameter exceeds 5 cm, it may induce clinical manifestations attributable to the compression of neighboring tissues and organs. Abdominal symptoms predominantly present as right hypochondriac discomfort or pain[7]. CT of hepatic hemangioma reveals the following findings: (1) Non-contrast scan demonstrates a well-defined, round or nearly circular hypodense lesion with homogeneous density; (2) During the arterial phase of the contrast-enhanced scan, the periphery of the lesion exhibits punctate, mottled, semicircular, and ring-shaped enhancement, with a density similar to that of the aorta; (3) In the subsequent portal venous phase, the contrast agent progressively fills the lesion in a centripetal manner, resulting in a gradual decrease in intensity; and (4) Delayed scanning demonstrates complete filling of the lesion with isodensity, comparable to the density of the liver. The larger the lesion, the longer the duration of isodensity filling, typically exceeding 3 minutes, displaying a “fast in and slow out” characteristic[8]. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors < 3 cm often exhibit an intraluminal and polypoid morphology. These masses typically demonstrate well-defined, homogeneous, soft-tissue attenuating characteristics. They exhibit notable enhancement during the arterial phase and sustain this enhancement during the portal venous or delayed phase[9]. Furthermore, regarding CT misdiagnosis, we posit that the primary factor contributing to this is the proximity of the left triangular ligament of the liver to the cardia of the gastric fundus. This anatomical arrangement predisposes it to protrude towards the cardia of the gastric fundus during gastric cavity distention. On CT imaging, this manifestation presents as a gastric cavity mass. Given that CT lacks the precision of EUS in delineating the intricate layers of the gastric wall, it becomes more susceptible to inaccuracies in lesion localization.

Based on prior research findings, EUS demonstrates superior accuracy compared to CT in discerning whether an SMT represents an intramural mass within the gastric wall or an extrinsic compression external to the gastric cavity. However, this heightened diagnostic capability of EUS concurrently places greater demands on the proficiency of EUS practitioners. During EUS procedures, conducting scans across different layers and at varying degrees of gastric cavity distension, coupled with meticulous image analysis, has the potential to mitigate the likelihood of such misdiagnoses in subsequent interventions. Although CT may not provide the same level of detail as EUS in revealing the layers of the gastric wall, it is possible that future research may explore the use of methods like thin-slice scanning or three-dimensional reconstruction to reduce the occurrence of such misdiagnoses.

| 1. | Motoo Y, Okai T, Ohta H, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Yamakawa O, Yamaguchi Y, Mouri I, Sawabu N. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of extraluminal compressions mimicking gastric submucosal tumors. Endoscopy. 1994;26:239-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Argüello L. Endoscopic ultrasonography in submucosal lesions and extrinsic compressions of the gastrointestinal tract. Minerva Med. 2007;98:389-393. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hedenbro JL, Ekelund M, Wetterberg P. Endoscopic diagnosis of submucosal gastric lesions. The results after routine endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rösch T, Kapfer B, Will U, Baronius W, Strobel M, Lorenz R, Ulm K. New Techniques Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography in Upper Gastrointestinal Submucosal Lesions: a Prospective Multicenter Study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:856-862. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen TK, Wu CH, Lee CL, Lai YC, Yang SS, Tu TC. Endoscopic ultrasonography to study the causes of extragastric compression mimicking gastric submucosal tumor. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:758-761. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mesny E, Mornex F, Rode A, Merle P. [Radiation therapy of hepatic haemangiomas: Review from a case report]. Cancer Radiother. 2022;26:481-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dong J, Zhang M, Chen JQ, Ma F, Wang HH, Lv Y. Tumor size is not a criterion for resection during the management of giant hemangioma of the liver. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:686-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aziz H, Brown ZJ, Baghdadi A, Kamel IR, Pawlik TM. A Comprehensive Review of Hepatic Hemangioma Management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:1998-2007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin YM, Chiu NC, Li AF, Liu CA, Chou YH, Chiou YY. Unusual gastric tumors and tumor-like lesions: Radiological with pathological correlation and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2493-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/