Published online Jun 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1527

Revised: February 20, 2024

Accepted: May 24, 2024

Published online: June 27, 2024

Processing time: 165 Days and 22 Hours

Natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) has emerged as a promising alternative compared to conventional laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) for treating gastric cancer (GC). However, evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of NOSES for GC surgery is limited. This study aimed to compare the safety and feasibility, in addition to postoperative complications of NOSES and LATG.

To discuss the postoperative effects of two different surgical methods in patients with GC.

Dual circular staplers were used in Roux-en-Y digestive tract reconstruction for transvaginal specimen extraction LATG, and its outcomes were compared with LATG in a cohort of 51 GC patients with tumor size ≤ 5 cm. The study was conducted from May 2018 to September 2020, and patients were categorized into the NOSES group (n = 22) and LATG group (n = 29). Perioperative parameters were compared and analyzed, including patient and tumor characteristics, postoperative outcomes, and anastomosis-related complications, postoperative hospital stay, the length of abdominal incision, difference in tumor type, postoperative complications, and postoperative survival.

Postoperative exhaust time, operation duration, mean postoperative hospital stay, length of abdominal incision, number of specific staplers used, and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire score were significant in both groups (P < 0.01). In the NOSES group, the postoperative time to first flatus, mean postoperative hospital stay, and length of abdominal incision were significantly shorter than those in the LATG group. Patients in the NOSES group had faster postoperative recovery, and achieved abdominal minimally invasive incision that met aesthetic requirements. There were no significant differences in gender, age, tumor type, postoperative complications, and postoperative survival between the two groups.

The application of dual circular staplers in Roux-en-Y digestive tract reconstruction combined with NOSES gastrectomy is safe and convenient. This approach offers better short-term outcomes compared to LATG, while long-term survival rates are comparable to those of conventional laparoscopic surgery.

Core Tip: Natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) in laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) has a reduced requirement for abdominal incision and associated complications, decreased pain and discomfort, and improved postoperative recovery. The combined use of dual circular staplers in Roux-en-Y digestive tract reconstruction in LATG has a lower incidence of postoperative stenosis complications. Postoperative exhaust time, operation duration, mean postoperative hospital stay, length of abdominal incision, number of specific staplers used, and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire score were significant in both groups. NOSES has emerged as a promising alternative compared to conventional LATG for treating gastric cancer.

- Citation: Zhang ZC, Wang WS, Chen JH, Ma YH, Luo QF, Li YB, Yang Y, Ma D. Perioperative outcomes of transvaginal specimen extraction laparoscopic total gastrectomy and conventional laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(6): 1527-1536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i6/1527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1527

Gastric cancer (GC) remains a highly fatal disease with unfavorable overall survival rates worldwide. It ranks as the fourth most common cancer in men and the seventh most common in women[1,2]. Despite notable advances in science and technology, the survival rate for GC is still unsatisfactory. Conventional laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) is a widely accepted approach for treatment of GC[3]. While it significantly minimizes surgical trauma, patients still experience physical and psychological distress due to the abdominal incision required for specimen extraction and digestive tract reconstruction. The prolonged duration of the operation and the postoperative recovery period not only cause psychological trauma on patients, but also pose additional emotional strains on their family. Natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) is a novel, minimally invasive surgical technique that enables specimens to be extracted through natural orifices such as the anus or vagina, using conventional laparoscopic instruments, transanal endoscopic microsurgery, or soft endoscopy, without the need for additional incisions[4]. Compared to conventional abdominal surgery, NOSES is associated with reduced postoperative pain, fewer wound complications, earlier recovery of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays. Although there are limited reports on NOSES in GC, an increasing number of patients have benefited from this novel technique. At the same time, for patients with potentially curable GC (i.e., nonmetastatic GC), NOSES may offer new prospects for achieving better clinical outcomes. Recent studies also suggested the feasibility of NOSES in advanced GC[5,6]. The benefits of NOSES over conventional LATG are gradually being accepted, including reduced surgical time and improved postoperative aesthetics. To address the aforementioned concerns, NOSES has emerged as an advanced laparoscopic technique that minimizes surgical injury, reduces the risk of wound complications, and alleviates postoperative pain by removing the specimen through natural orifices connected to the external environment, such as the vagina or anus. Several studies have reported that NOSES can reduce the use of postoperative analgesia, accelerate the recovery of intestinal function, and shorten the length of hospital stay for gastric surgery compared to conventional specimen extraction approaches[7,8].

There are two main choices for digestive tract reconstruction in total gastrectomy, the linear stapler and circular stapler, which are typically performed to restore continuity of the alimentary canal. Esophagojejunostomy using a linear stapler is associated with a higher likelihood of anastomotic leakage or stenosis in clinical practice[9,10]. In the era of open surgery and laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy, surgeons preferred circular staplers. There are several advantages of using a circular stapler. First, it conforms to the natural physiological state of the digestive tract; second, it can avoid the common opening made by a linear stapler; and third, the anastomosis created by a circular stapler is less prone to narrowing. One of the two circular staplers we used is OrVil™, which is inserted through the mouth to complete the esophagojejunostomy. OrVil is a device designed to make it easier to perform this procedure in a minimally invasive manner, thereby avoiding difficulties caused by a short esophageal stump and reducing the need for purse-string sutures[11]. Studies have indicated that the application of OrVil for gastrointestinal reconstruction procedures can be both safe and effective, with comparable outcomes to the traditional circular stapling techniques[12,13]. In this study, we introduced a dual circular stapler combined with NOSES for LATG for GC. At a distance of 40 cm from the gastroenterostomy of the esophagus, we performed an anastomosis of the jejunum using a circle stapler with a diameter of 21 mm, thus achieving Roux-en-Y digestive tract reconstruction following total gastrectomy.

A total of 51 patients who were diagnosed with GC and underwent LATG with D2 regional lymph node dissection between May 2018 and September 2020 at the Department of General Surgery, Xinqiao Hospital were included in this study, and categorized into the NOSES group and LATG group. The patients in the NOSES group were selected based on the following criteria: (1) Female patients with stage II or II GC with the lesion located in the fundus or showing poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, requiring total gastrectomy; (2) Patients who did not require fertility preservation and had no history of gynecological or obstetric diseases; and (3) Written informed consent was obtained. The remaining patients were assigned to the LATG group.

Two types of gastrointestinal reconstructive surgery were evaluated for their clinical outcomes. Patient data were collected from medical records, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), extent of lymph node dissection, anastomosis method, anastomosis-related complications, number of stapler cartridges used, time required for anastomosis, operation time, estimated blood loss, days to first flatus, liquid diet time, length of postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. The resected specimens were histologically assessed for the length of proximal and distal margins, number of harvested lymph nodes, and TNM stage, according to the 8th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC).

Patients were routinely followed up at outpatient clinics 2 weeks after discharge and at 3 and 6 months after the operation, and then every 3 months thereafter. The presence of postoperative symptoms was recorded for each patient during each follow-up visit, and included reflux, dyspepsia, dumping syndrome, postprandial discomfort, and diarrhea. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Preoperative chemoradiotherapy was performed by radiation oncologists and medical oncologists based on the clinical stages and patients’ preferences, which was not included in the protocol of this trial. For patients who received preoperative chemotherapy, the surgery was performed 6-8 weeks after the completion of chemotherapy. Before surgery, these patients were evaluated for eligibility, and assigned to treatment groups according to the trial protocol.

All surgeons were qualified and experienced. The surgeon stood on the left side of the patient, with the first assistant standing on the right side. During the operation, the surgeon and the first assistant switched positions as needed. The camera assistant stood between the patient’s legs. Under general anesthesia, the abdomen, pelvis and vaginal canal were disinfected with diluted iodophor water. In the reverse Trendelenburg position with the legs apart, five trocars were inserted. During the operation, the greater curvature was mobilized along the transverse colon using a harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, United States). The left gastric vessels were identified after opening the bursa omentalis. The greater curvature was mobilized until the splenic hilum for complete omentectomy. The infrapyloric lymph nodes were dissected toward the duodenum and the distal gastric vessels (right gastroepiploic and right gastric) were transected using the harmonic scalpel. The duodenum was then cut using a laparoscopic 60-mm stapler (EndoGIA, Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States), and the roots of the left gastric vessels were exposed. The left gastric vein was divided using the harmonic scalpel and the intact left gastric artery was used to expose the other branches of the celiac trunk. Lymph node dissection was continued along the hepatic and splenic arteries. The left gastric artery was subsequently divided near its root after double clipping. Dissection was then extended to the esophagocardiac junction at the lesser curvature and these lymph nodes were included in the resection specimen. The stomach was divided at the esophagogastric junction using a 60-mm laparoscopic stapler, and the specimen was placed and sealed in a retrieval bag.

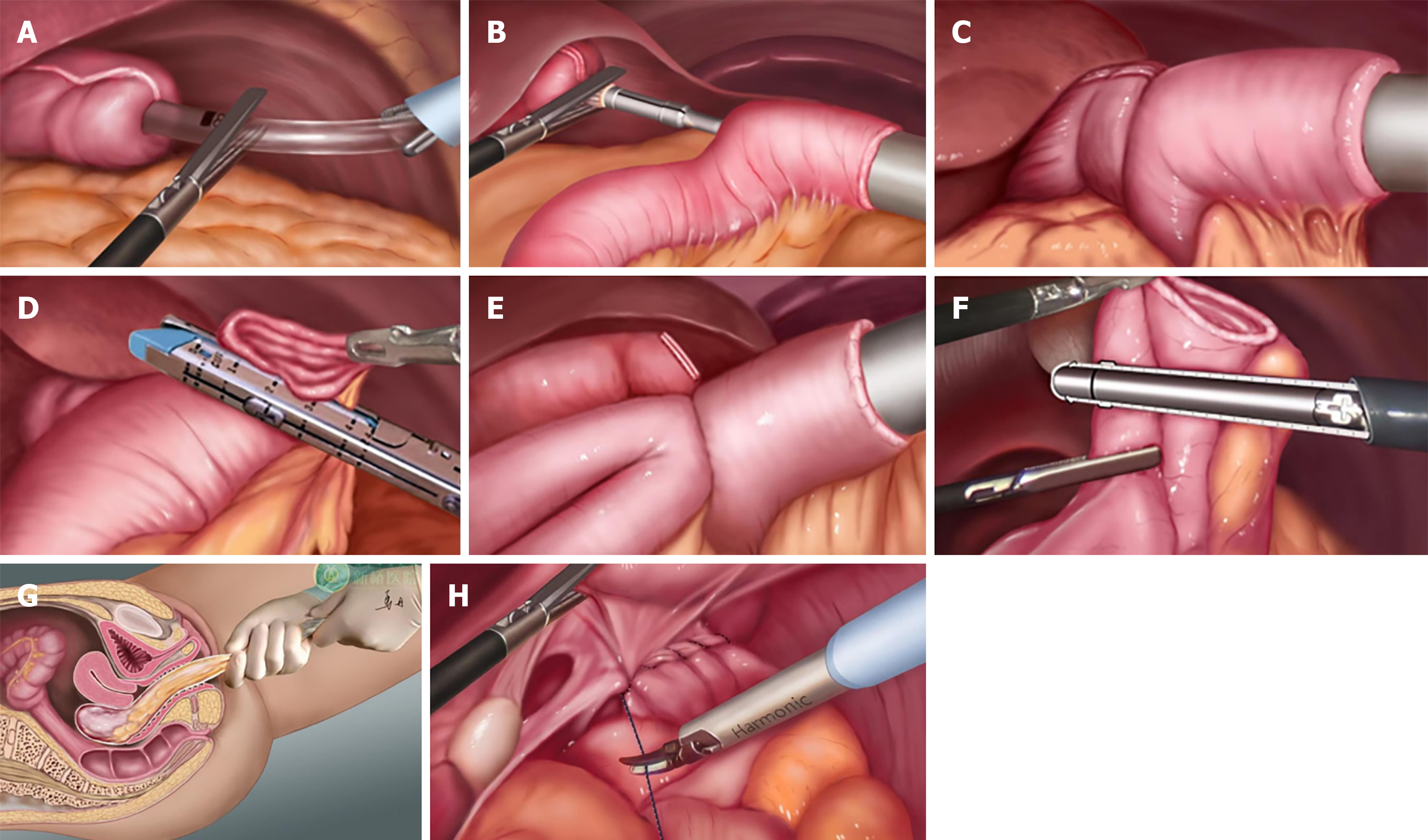

Following the dual circular staplers operating instructions, the anvil of OrVil™ (Covidien) was placed through the mouth. Under the laparoscopic monitoring, the head joint of the anvil was pulled out from the esophageal stump (Figure 1A). The jejunum and mesentery was cut at a distance of 30 cm from the flexor’s ligament using an endoscopic linear cutter. The operating handle of the 25-mm diameter circular stapler was then placed into the abdominal cavity through the left upper abdominal puncture hole (Figure 1B), with posture adjustments made to avoid damage to the gut. A plastic specimen bag that was inserted from the left upper abdominal puncture hole was used to isolate the hole from the stapler. Under laparoscopic monitoring, the esophagojejunostomy of Roux-en-Y reconstruction was performed using the first circular stapler (Figure 1C). The jejunal stump was closed with a 60-mm linear stapler (Figure 1D). Subsequently, a 3-cm transverse transvaginal posterior colpotomy was performed under laparoscopic control, and the incision was enlarged bluntly using the fingers. Another anvil with a diameter of 21 mm was inserted through the vagina and into the distal jejunum at 40 cm from the esophagojejunostomy. The anvil was secured with a purse-string suture under laparoscopy (Figure 1E). The handle of the stapler was inserted into the proximal jejunum via the left upper abdominal puncture hole too, with isolation from a plastic specimen bag. The end-to-side jejunostomy was fashioned using the second circular stapler and the stump was closed intracorporeally. The jejunal stump was closed with a 60-mm linear stapler (Figure 1F). The specimen was grasped with an ovary clamp through the vaginal incision and carefully pulled into the vagina (Figure 1G). The specimen was always contained within a retrieval bag, and there was no contact between the specimen and the abdominal cavity or the vagina throughout the procedure. Following removal of the specimen, the horizontal incision on the posterior wall of the vagina was closed using a running absorbable suture (Figure 1H), and an abdominal drain was used. Meticulous closure of the colpotomy and the use of an abdominal drain minimized the risk of postoperative complications.

The primary outcomes in this trial study were significantly different regarding postoperative abdominal incision length and postoperative exhaust time. Secondary outcomes included surgical quality, pathological outcomes, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative discharge time, and long-term tumor outcomes. Two distinct surgical procedures were used in this trial, and intraoperative hemorrhage was measured by subtracting the weight of the irrigation fluid from the suction blood and wet gauze. Pathology specimens were processed and assessed by the Department of Pathology, Xinqiao Hospital of Army Medical University in accordance with the Chinese Standardization Criteria for Tumor Pathology Diagnosis. The macroscopic completeness and quality of the specimen were assessed by pathologists according to previously reported criteria. The tumor stage was determined according to the 8th edition of the UICC TNM staging system. All enrolled patients were evaluated using the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIQ) and the Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) scales. These questionnaires were distributed and collected by specialized staff, without the participation of the surgeons. All patients were asked to complete a questionnaire at the time of postoperative assessment. Follow-up principles were based on the Chinese standards of diagnosis and treatment of GC. Patients were asked to attend the hospital’s outpatient department for documented visits and examinations. Specialized staff were arranged to collect follow-up data by making phone calls or sending emails if the patient did not come on time. An independent statistician monitored the data and focused on the safety markers. All data were recorded in the case report form by the trial investigators. Two different investigators checked the records for confirmation. Although no blinding to treatment allocation was incorporated in this trial, the outcomes were evaluated and recorded by two blinded assessors according to medical documents without knowledge of the grouping allocation.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (La Jolla, CA, United States) and displayed as the mean ± SE. Comparisons between two experimental groups were conducted using nonparametric tests, while differences among more than two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests. The primary outcome measure was the 30-day postoperative complication rate (Clavien–Dindo Grade II or higher), which was compared using Fisher’s exact test without adjustment for baseline characteristics. The difference and 95% confidence interval (CI) in postoperative complication rate were evaluated using unadjusted Miettinen–Nurminen scoring methods. Adjusted analysis for the primary outcome was conducted as per the predefined statistical analysis plan (Supporting Information: Trial Protocol), using multilevel logistic regression for the following factors: sex, age, ASA classification, BMI, abdominal surgery history, preoperative chemoradiotherapy, tumor size, pathological T stage, and pathological N stage. All P values were two-sided and considered significant when < 0.05.

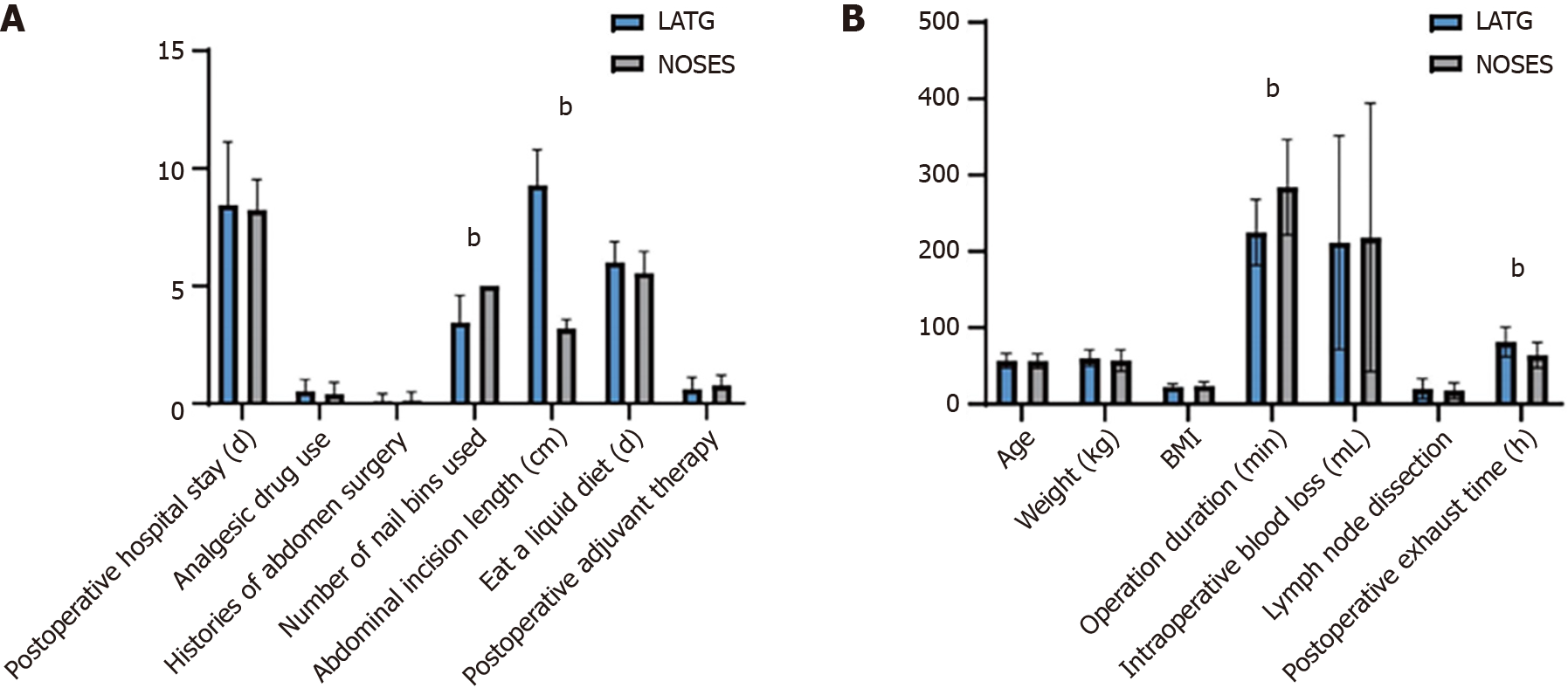

Between May 2018 and September 2020, 51 eligible patients with GC were randomized to receive either NOSES or LATG (Table 1). The surgeons were on the same team after grouping, and both groups were similar regarding age, BMI, extent of lymph node dissection, time to eat, and tumor stage with no significant differences in statistical analysis (Figure 2). The average total operating time was 284.23 min in the NOSES group and 221.15 min in the LATG group. Notably, the postoperative exhaust time was significantly shorter in the NOSES group (63.86 h) than in the LATG group (81.27 h). Nonetheless, there were no significant differences between the two groups (Figure 2). No patients were lost to follow-up after 2 years, four (7.8%) experienced recurrence (locoregional recurrence or distant metastases), one (1.9%) died, two (3.9%) had postoperative increase in carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increase, and two (3.9%) experienced postoperative hemorrhage.

| NOSES | LATG | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 0 (0) | 23 (79.3) |

| Female | 22 (100) | 6 (20.7) |

| Age (year), mean (SD) | 56.59 | 56.86 |

| ASA classification, n (%) | ||

| I | 14 (63.7) | 19 (65.5) |

| II | 8 (36.3) | 10 (34.5) |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL, SD) | 218.18 | 211.72 |

| Concomitant disease, n (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 7 (32) | 8 (27.6) |

| Diabetes | 2 (9) | 4 (13.8) |

| Cardiac | 10 (4.5) | 10 (3.4) |

| Abdominal incision length (cm) | 3.18 | 9.28 |

| Postoperative exhaust time (h, SD) | 63.86 | 81.28 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), n (%) | ||

| Underweight < 18.5 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (3.4) |

| Normal 18.5-23.9 | 2 (9.1) | 19 (65.5) |

| Overweight 24-27.9 | 16 (72.8) | 8 (27.6) |

| Obese ≥ 28 | 3 (13.6) | 1 (3.5) |

| With previous abdominal surgery, n (%) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (10.3) |

| Preoperative CEA (ng/mL), n (%) | ||

| < 5 | 20 (91) | 29 (100) |

| ≥ 5 | 2 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Clinical TNM stage, n (%) | ||

| I | 9 (40.9) | 13 (44.8) |

| II | 4 (18.1) | 1 (3.5) |

| III | 9 (41) | 15 (51.7) |

| Mean operation time (minutes) | 284.23 | 221.15 |

| Undergo postoperative chemotherapy, n (%) | 17 (77.3) | 18 (62) |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | ||

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative liver metastasis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bone metastasis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pulmonary infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative anastomotic leakage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative abdominal infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Incision-related complications | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative intestinal obstruction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

During the 2-year follow-up period, one death occurred in the control group because of myocardial infarction. Two patients showed an increase in CEA levels and one patient developed bone metastasis in the experimental group. In the control group, one patient experienced postoperative abdominal metastasis or recurrence, one patient had liver metastasis, and one patient had pulmonary infection. Postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage, abdominal infection, intestinal obstruction, incision-related complications, and deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism were observed. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of these complications between the two groups (Table 2).

| P value | Mean of LATG | Mean of NOSES | Difference | SE of difference | |

| Operation time (minutes) | 0.000215 | 225.0 | 284.2 | -59.23 | 14.81 |

| Postoperative exhaust time (hours) | 0.001373 | 81.28 | 63.86 | 17.41 | 5.130 |

| Abdominal incision length (cm) | < 0.000001 | 9.276 | 3.182 | 6.094 | 0.3357 |

| Number of anvil used | < 0.000001 | 3.586 | 5.000 | -1.414 | 0.2021 |

| BIQ score | < 0.000001 | 31.10 | 41.45 | -10.35 | 0.4849 |

| Age | 0.921270 | 56.86 | 56.59 | 0.2712 | 2.729 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.348282 | 60.37 | 57.09 | 3.283 | 3.466 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.368479 | 22.78 | 23.89 | -1.106 | 1.218 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 0.884527 | 211.7 | 218.2 | -6.458 | 44.23 |

| Lymph node dissection | 0.431364 | 20.24 | 17.59 | 2.650 | 3.341 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 0.723817 | 8.448 | 8.227 | 0.2210 | 0.6218 |

| Analgesic drug use | 0.453535 | 0.5172 | 0.4091 | 0.1082 | 0.1431 |

| History of abdominal operation | 0.724385 | 0.1034 | 0.1364 | -0.03292 | 0.09281 |

| Eat a liquid diet (days) | 0.079366 | 6.000 | 5.545 | 0.4545 | 0.2537 |

| Postoperative adjuvant therapy | 0.255226 | 0.6207 | 0.7727 | -0.1520 | 0.1321 |

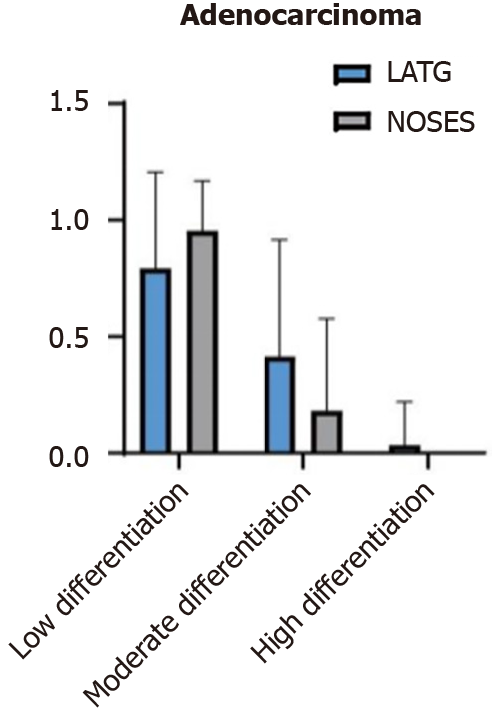

The postoperative pathological findings were compared between the two groups. There was no significant difference in the pathological TNM stage or other pathological characteristics (Figure 3).

All operations in both groups were successfully completed. However, the NOSES group had a significantly longer mean operating time (NOSES 284.2 minutes vs LATG 221.5 minutes), and higher mean BIQ score (NOSES 41 vs LATG 31). Additionally, there was a significant difference between the two groups for the mean number of anvils used (LATG 3.5 vs NOSES 5). The mean abdominal incision length was longer in the LATG group (9.3 cm) than in the NOSES group (3.1 cm).

The NOSES group demonstrated significantly better postoperative gastrointestinal recovery, as evidence by a shorter mean time to first flatus emission (NOSES 63.8 hours vs LATG 81.3 hours), and a shorter mean time to consume a semifluid diet (NOSES 5.5 days vs LATG 6 days). Although there was a significant difference in the time to exhaust, no significant difference was found between the two groups for mean length of hospital stay (LATG 8.5 days vs NOSES 8.2 days).

Laparoscopic surgery for GC has several advantages of reduced surgical trauma, less gastrointestinal interference, minimal bleeding (no or less need for blood transfusion), decreased postoperative pain, shorter recovery time, smaller incision scars, and significantly lower rates of postoperative complications. As a result, laparoscopic surgery has become more popular for treatment of GC. In the early stage of laparoscopic surgery, abdominal incision was necessary for specimen collection and release. Over time, the introduction of NOSES technology has gradually shifted the concept of minimally invasive surgery. There are three potential natural orifices for abdominal specimen extraction in humans, transanal, transoral and transvaginal.

Reconstruction of the digestive tract after total gastrectomy is difficult and is a focus of debate and research[14,15]. The principles of gastrointestinal reconstruction in GC surgery include ensuring oncological safety, safe anastomosis, not increasing the risk of anastomotic complications, reducing functional damage, and ease of operation[16,17]. There are several options for digestive tract reconstruction after total gastrectomy, including jejunal interposition, double channel method, storage bag, loop anastomosis. Roux-en-Y anastomosis has become the most commonly used method for digestive tract reconstruction. The choice of which method to implement for esophagojejunal anastomosis, whether to use a tubular stapler or a linear cutter, and determining which method is superior, are all urgent questions[18,19]. Where is the esophagojejunal anastomosis pathway for complete LATG? We believe that using a linear cutter to perform esophagojejunal lateral anastomosis and complete endoscopic total gastrectomy for digestive tract reconstruction may be the most common choice using the existing anastomotic instruments. However, there are still many problems with linear staplers, such as the need to preserve a longer segment of the lower esophagus. Therefore, it is necessary to clearly understand the appropriate indications. One of the advantages of circular staplers is that they eliminate the need for manual purse-string sutures, simplifying the surgical procedure. We believe that the breakthrough in research and development of a tubular stapler suitable for complete laparoscopic esophagojejunostomy means that the use of tubular staplers for complete endoscopic total gastrectomy and digestive tract reconstruction may become mainstream again.

With the progress of minimally invasive technology, an increasing number of people can accept the use of natural cavity specimen retrieval technology. To date, there are no studies reporting on NOSES compared to conventional LATG. Our study provides clinicians with valuable reference data related to both surgical options. Our findings indicated that the experimental group showed significant improvements in terms of gastrointestinal recovery time and abdominal incision length. Gastrojejunostomy may be difficult to perform through a small incision in obese patients due to poor visualization, and extracorporeal anastomosis has been associated with tissue traction, injury, and an increased risk of infection. In such cases, an extension of the laparotomy may be necessary to obtain a better view and ensure a secure anastomosis during gastrectomy for GC. Additionally, tumors located at the gastroesophageal junction may require a longer remaining healthy esophageal stump to ensure adequate negative margins, which may not be conducive to esophagojejunostomy. In terms of esophagojejunal anastomosis, the use of a linear cutting stapler requires a high level of technical skill. In recent years, many surgeons have proposed the use of linear staplers in LATG, such as the π anastomosis and overlap techniques[20,21]. One disadvantage is that a longer segment of the lower esophagus is needed, while ensuring sufficient safety of the incisional margin. It is generally easier to maintain a 4.5-6.0-cm length of the abdominal segment of the esophagus for patients with tumors located in the gastric body, while it is challenging for upper GC to meet this condition, particularly for tumors in the esophagogastric junction that invade the dentate line. Therefore, it is not suitable for patients with high esophageal resection lines, and its indications are strictly limited. Although it is ensured that the lower segment of the esophagus remains 4.5-6.0 cm when the esophagus is free and naked, in clinical practice, most of the broken ends retract into the esophageal hiatus after the esophagus is severed. To prevent retraction of the esophageal stump into the chest cavity, Lee et al[15] attempted to suture one needle on each side of the esophageal stump opening to assist pulling and inserting a linear cutter into the esophageal opening, thereby reducing the difficulty of anastomosis. However, completing the anastomosis without disconnecting the esophagus and verifying the incision margin for safety does not adhere to the principles of oncology. Moreover, traction during the anastomosis can reduce tension at the anastomotic site during the operation, but once the esophagus is severed, traction is no longer present, leading to inevitable tension-related issues.

Esophagojejunostomy using a circular stapler has become a standard technique in open total gastrectomy. Therefore, in LATG, esophagojejunostomy using a circular stapler has emerged as the preferred method. The method we used to reconstruct the digestive tract after total gastrectomy included a novel circular stapling technique that could be used to complete the esophagojejunostomy using a transorally inserted anvil (OrVil). This technique avoids the difficulties associated with a short esophageal stump, especially the purse-string suture, and can ensure a high-quality anastomosis, thereby preventing complications such as stenosis and anastomotic leaks. This surgical method does not require endoscopic purse string suture, nor does it require the surgeon to insert a stapler anvil into the abdominal cavity, which seems to simplify the surgical process. For GC at a higher position, a higher incision margin can be obtained than the suture purse string method, ensuring a sufficient safe esophageal incision margin. However, pulling out the anvil catheter through the abdominal cavity increases the risk of abdominal contamination and does not comply with the principle of sterility. In addition, OrVil is inserted through the mouth, which reduces the difficulty associated with the suture purse and insertion of the anvil via the abdominal cavity. However, it requires the assistance of an anesthesiologist, and it is difficult to pass the anvil through the esophageal stricture, which can cause esophageal injury. There can be accidents if the anvil becomes stuck in the esophagus and a digestive endoscope is needed for removal. In order to overcome the difficulties in purse-string suturing of the lower esophagus and insertion of the anvil head into the esophagus, a newly developed transoral device (OrVil™), equipped with an anvil, was designed by Covidien. This device was first reported in 2009 for application in complete LATG and digestive tract reconstruction[21].

With reference to the application of a circular stapler in esophagojejunal anastomosis, our team pioneered a technique using a smaller circular stapler (diameter 21 mm) for complete jejunojejunostomy. This approach makes the two anastomoses more reliable and convenient, resolving the problems associated with frequently used methods. Our study suggests that laparoscopic reconstruction of Roux-en-Y anastomosis with a dual circular stapler and NOSES is safer, more feasible and less invasive than other methods. Based on our results, when considering short-term efficacy and 3-year follow-up, it is evident that a longer operating time contributes to increased anesthesia and cost; however, it will decrease as the surgical team gains experience and proficiency.

Our novel method (combined use of dual circular staplers in Roux-en-Y digestive tract reconstruction with NOSES in LATG) provides significant advantages over conventional LATG, including enhanced visibility during the anastomosis, reduced requirement for abdominal incision and associated complications, decreased pain and discomfort, improved postoperative recovery, and lower incidence of postoperative stenosis complications. However, further studies with larger populations and longer follow-up are necessary to obtain more comprehensive results.

| 1. | Sylla P, Rattner DW, Delgado S, Lacy AM. NOTES transanal rectal cancer resection using transanal endoscopic microsurgery and laparoscopic assistance. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1205-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sumer F, Kayaalp C, Ertugrul I, Yagci MA, Karagul S. Total laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with transvaginal specimen extraction is feasible in advanced gastric cancer. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;16:56-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun P, Wang XS, Liu Q, Luan YS, Tian YT. Natural orifice specimen extraction with laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:4314-4320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nishimura A, Kawahara M, Honda K, Ootani T, Kakuta T, Kitami C, Makino S, Kawachi Y, Nikkuni K. Totally laparoscopic anterior resection with transvaginal assistance and transvaginal specimen extraction: a technique for natural orifice surgery combined with reduced-port surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4734-4740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yagci MA, Kayaalp C, Novruzov NH. Intracorporeal mesenteric division of the colon can make the specimen more suitable for natural orifice extraction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:484-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Choi WJ, Paik WY, Jeong CY, Park ST, Choi SK, Hong SC, Jung EJ, Joo YT, Ha WS. Trans-vaginal specimen extraction following totally laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xiao Y, Xu L, Zhang JJ, Xu PR. Transvaginal laparoscopic right colectomy for colon neoplasia. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020;8:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Du J, Xue H, Hua J, Zhao L, Zhang Z. Intracorporeal classic circular-stapled gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: A simple, safe "intraluminal poke technique" for anvil placement. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang Q, Yang KL, Guo BY, Shang LF, Yan ZD, Yu J, Zhang D, Ji G. Safety of early oral feeding after total laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer (SOFTLY-1): a single-center randomized controlled trial. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:4839-4846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayata K, Yamaue H. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y reconstruction using conventional linear stapler in robotic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Oncol. 2020;33:9-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | He L, Zhao Y. Is Roux-en-Y or Billroth-II reconstruction the preferred choice for gastric cancer patients undergoing distal gastrectomy when Billroth I reconstruction is not applicable? A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gong CS, Kim BS, Kim HS. Comparison of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using an endoscopic linear stapler with laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy using a circular stapler in patients with gastric cancer: A single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8553-8561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang ZC, Luo QF, Wang WS, Chen JH, Wang CY, Ma D. Development and future perspectives of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery for gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:1198-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, Quispe L, Zevallos A, Buleje JL, Cho CE, Sarmiento M, Pinto JA, Fajardo W. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;181:103841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Lee SR, Kim HO, Son BH, Shin JH, Yoo CH. Laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy versus open total gastrectomy for upper and middle gastric cancer in short-term and long-term outcomes. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guan X, Liu Z, Parvaiz A, Longo A, Saklani A, Shafik AA, Cai JC, Ternent C, Chen L, Kayaalp C, Sumer F, Nogueira F, Gao F, Han FH, He QS, Chun HK, Huang CM, Huang HY, Huang R, Jiang ZW, Khan JS, da JM, Pereira C, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Son JT, Kang L, Uehara K, Lan P, Li LP, Liang H, Liu BR, Liu J, Ma D, Shen MY, Islam MR, Samalavicius NE, Pan K, Tsarkov P, Qin XY, Escalante R, Efetov S, Jeong SK, Lee SH, Sun DH, Sun L, Garmanova T, Tian YT, Wang GY, Wang GJ, Wang GR, Wang XQ, Chen WT, Yong Lee W, Yan S, Yang ZL, Yu G, Yu PW, Zhao D, Zhong YS, Wang JP, Wang XS. International consensus on natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) for gastric cancer (2019). Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020;8:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhu Q, Yu L, Zhu G, Jiao X, Li B, Qu J. Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy and Sigmoidectomy Combined With Natural Orifice Specimen Extraction Surgery (NOSES) for Synchronous Gastric Cancer and Sigmoid Colon Cancer: A Case Report. Front Surg. 2022;9:907288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Salih AE, Bass GA, D'Cruz Y, Brennan RP, Smolarek S, Arumugasamy M, Walsh TN. Extending the reach of stapled anastomosis with a prepared OrVil™ device in laparoscopic oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:961-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jung YJ, Kim DJ, Lee JH, Kim W. Safety of intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using trans-orally inserted anvil (OrVil) following laparoscopic total or proximal gastrectomy - comparison with extracorporeal anastomosis. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Burden of Gastric Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 1081] [Article Influence: 180.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 21. | Jeong O, Park YK. Intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using the transorally inserted anvil (OrVil) after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2624-2630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/