INTRODUCTION

Rectal cancer is one of the challenging colorectal conditions and is responsible for a significant portion of cancer-related morbidity and mortality. The current gold standard treatment of rectal cancer is total mesorectal excision (TME) which aims at reducing the incidence of local recurrence[1]. Patients with locally advanced rectal cancers should be treated upfront with neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy to help downstage the tumor and clear lateral lymph node involvement. As neoadjuvant treatments evolved to include the new concept of total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT)[2], an increasing number of patients were found to exhibit complete response to neoadjuvant therapy with no residual tumor cells in the rectum or the lymph nodes after radical resection, known as pathologic complete response. The complete response of rectal cancers to neoadjuvant treatment inspired one of the colorectal surgery leaders, Dr Angelita Habr-Gama, the concept of non-operative management (NOM) of rectal cancer in patients with a complete response to treatment. NOM simply entails that patients with a complete response may not undergo TME as previously planned, but rather be subject to strict surveillance to detect early recurrence of cancer, if occurred, known as the Watch & Wait strategy[3]. In this editorial, we highlight the main controversies on NOM of rectal cancer, with implications for future research directions.

‘WHO’ SHOULD RECEIVE NOM?

Patients eligible for NOM should be those with a clinical complete response after neoadjuvant radiation. However, even some patients with a clinical near-complete response may also be eligible for NOM as 15% of them have evidence of complete pathologic response after surgery[4]. Some authors suggest that the ideal candidates for NOM are patients with middle or low rectal cancers who would otherwise have a low colorectal/coloanal anastomosis or an abdominoperineal resection if were surgically treated as planned[5]. However, even patients with upper rectal cancers may opt for NOM to avoid the consequences of surgery, namely low anterior resection syndrome and autonomic nerve injury with subsequent genitourinary dysfunction.

Consistent with the current guidelines, imaging and endoscopy should be the standard tools for assessment of clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy, in comparison to the baseline before initiation of treatment[6]. Combined with digital rectal examination, these tools have a very high accuracy in excluding residual tumors and verifying a complete response[7]. The evaluation criteria for a clinical complete response of rectal cancer comprise a complete disappearance of all cancerous lesions in clinical examination as shown by the absence of residual ulceration, masses, or mucosal irregularity together with the absence of residual nodal disease on imaging with a reduction in short axis of pathologic lymph nodes to less than 1 cm[8,9].

The conclusions of follow-up imaging after treatment may not be very reliable. Gefen et al[10] showed that restaging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had a fair concordance with the pathology report for the T stage (kappa -0.316) and slight concordance for the N stage (kappa -0.11) and CRM status, (kappa = 0.089). The concordance was even lower when TNT was used. Some 73% of patients with pathologic N+ stage had no evidence of nodal involvement in the restaging MRI which calls for caution when interpreting the MRI assessment of nodal disease. Because of imaging inaccuracies, patients with a residual disease and false negative imaging may be treated with NOM, and patients who responded to treatment yet had false positive imaging be precluded from NOM and undergo surgery that can otherwise be unnecessary.

Another controversy regarding patient selection for NOM is patients with adverse baseline features such as involved mesorectal fascia, extramural venous invasion, and extensive lymph node involvement[11]. In addition, ulcerating and annular lesions may not be eligible for NOM since they may undergo extensive fibrosis after radiation therapy with subsequent luminal stenosis that may hinder endoscopic assessment and follow-up[9]. Furthermore, another hurdle related to the inaccurate assessment of clinical response is the potential of missing residual nodal disease even with a complete mucosal response. A large database analysis found that 8% of patients with complete mucosal response had positive lymph nodes on pathologic assessment after surgery[12]. These patients with residual nodal disease may not have been detected using imaging which has a low sensitivity in detecting nodal involvement in rectal cancer[13]. This calls for more novel tools for the assessment of complete response after neoadjuvant therapy, some of these tools, including dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, ctDNA, and molecular biomarkers, are still under investigation[5].

Selection of patients for NOM should ideally be based on clinical complete response as evident by clinical and imaging tools. Recently, some prediction models have been developed to help predict complete response after neoadjuvant therapy. Shin and colleagues[14] analyzed data of 1089 patients with rectal cancer and constructed a prognostic model for complete response to neoadjuvant therapy that incorporated clinical N0 stage, small (< 4 cm) and well differentiated cancers. Artificial intelligence (AI) was also used to generate predictive models based on pretreatment MRI. A systematic review[15] of 21 AI studies based on MRI-predicted complete response to neoadjuvant therapy found AI to have an exceptional accuracy with a pooled area under the curve of the models assessed of 0.91 and pooled sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 86%, respectively.

‘WHEN’ TO REASSESS THE RESPONSE OF RECTAL CANCER TO NEOADJUVANT TREATMENT?

Another controversy related to patient selection is when is the optimal time to assess the response to treatment. It has been shown that a too-early assessment may erroneously render a wrong judgment of an incomplete response. Generally, an interval >8 wk after neoadjuvant treatment is needed before reassessment to measure the maximal tumor regression. However, this interval has not been agreed upon in the literature and could range from four to 20 wk. Some investigators suggested an 8-wk interval while others thought a 12-wk interval would be ideal before reassessment[16,17]. The minimum cutoff of 8 wk was selected because a reassessment earlier than 8 wk may fail to detect complete regression of cancer that can be still ongoing, and thus could be misinterpreted as an incomplete response. Based on the same concept, an interval of > 8 wk before reassessment was proposed to allow for maximal tumor regression and thus more precise assessment of response. Nonetheless, this lack of consensus is considered another important controversy that needs more research to resolve.

‘HOW’ SHOULD PATIENTS UNDERGOING NOM BE FOLLOWED UP?

The standard methods used for surveillance after NOM include digital rectal examination, Pelvic MRI, and endoscopy. In addition, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-level assessment and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may be also used for surveillance. The protocol used for follow-up of patients undergoing NOM quite varies. The first protocol described by Habr-Gama et al[18] entailed follow-up with a digital rectal examination, proctoscopy, and CEA level measurement every 6-10 wk in the first two years then the follow-up is scheduled every three months in the third year and every 6 months afterward. Another follow-up protocol entailed digital rectal examination and MRI every six months in the first two years and endoscopic examination plus CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis in the first two years[17].

A standardized surveillance program for the NOM of rectal cancer has yet to be established. Each society guideline offers different recommendations regarding the methods and frequency of surveillance. This diversity in guidance is logical, given the varying nature of disease recurrence, which may necessitate different surveillance approaches that would involve physical examinations, blood markers such as CEA, imaging, and endoscopy.

While a comprehensive review[19], aggregating data from eight meta-analyses of RCTs, revealed a unanimous and significant benefit of surveillance strategies, the question of whether intensive or less intensive follow-up regimens confer superior outcomes is still open. According to ASCO guidelines[20], for patients with stage II or III disease, the initial 2-4 years after surgery should involve more rigorous testing, as approximately 80% of recurrences are detected within the first two years. Conversely, the NCCN[6] and ESMO[21] guidelines recommended a semi-annual to annual abdomen and chest CT scanning over 5 years, considering that up to 10% of recurrences occur after 3 years. ASCRS[22] guidelines closely align with these recommendations, emphasizing the potential survival benefits of follow-up for patients with stage I disease. Less intensive surveillance programs are suggested by ESMO and ACPGBI[23], consisting of a minimum of two CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with a regular CEA-level assessment in the first three years.

Surveillance strategies may also vary based on the type of initial management received. For instance, the ASCRS[22] and NCCN[6] guidelines advocate for a more intensive approach for patients treated with transanal excision, while ASCO suggests an equally intensive approach for patients who did not receive radiotherapy. Overall, the NCCN guidelines[6] tend to recommend more frequent surveillance compared to other programs. A survey conducted by the ASCRS in 2000[24] assessed the methods and frequency of follow-up. Interestingly, the survey revealed a wide range of diagnostic modalities utilized in surveillance, with only 50% of surgeons adhering to the recommendations of ASCRS guidelines. This discrepancy could be attributed to the divergent guidelines, making it challenging for surgeons to determine the most effective surveillance method.

‘WHAT’ SHOULD BE DONE WHEN LOCAL RECURRENCE AFTER NOM IS DETECTED?

Disease recurrence after NOM is the most serious adverse effect of this treatment strategy. The 3-year cumulative risk of local recurrence after NOM in patients with clinical complete response is approximately 25%[25]. The pretreatment T stage is considered the most influential risk factor for local recurrence after NOM. The risk of local recurrence tends to increase by 10% for every transition in the T stage[26]. Early recognition of local recurrence in the setting of NOM is of paramount importance. Patients in whom local recurrence was detected early may have similar survival outcomes to patients with an incomplete response after neoadjuvant treatment[27]. However, other studies implied a negative impact of local recurrence on survival[28].

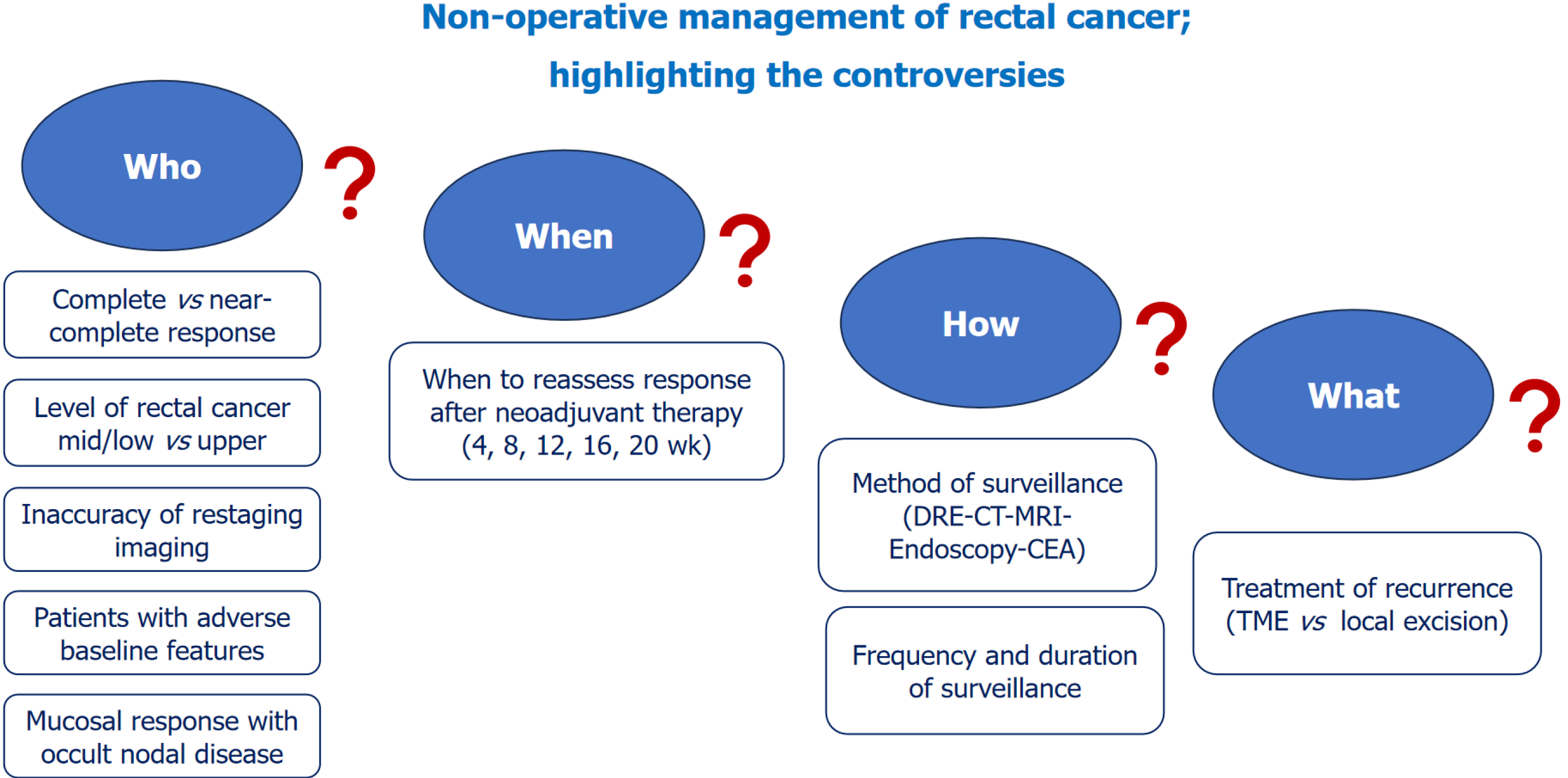

Management of local recurrence in the setting of NOM may represent a clinical challenge. Local recurrences may be managed by either a radical or local excisional surgery. While local excision preserves the rectum and obviates the risk of major surgery associated with proctectomy, it may be associated with considerably higher rates of positive resection margins, and thus disease recurrence. Most (> 90%) local recurrences of rectal cancer can be treated with salvage sphincter-sparing surgery[29]. Smith et al[30] reported an 83% R0 rate after treating six patients with local recurrence after NOM for rectal cancer. On the other hand, conflicting outcomes were reported after wide local excision of local recurrence after NOM. While Li et al[31] successfully treated two patients with local recurrence after NOM by local excision, another study that treated local recurrence after NOM by transanal endoscopic surgery reported positive surgical margins that warranted an abdominoperineal resection[32]. Despite that local recurrence after NOM may be adequately managed, there remains the risk of distant metastatic disease that can be as high as 8%-10%[33]. Figure 1 illustrates the main controversies about NOM of rectal cancer.

Figure 1 The main controversies about non-operative management of rectal cancer.

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; DRE: Digital rectal examination; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; TME: Total mesorectal excision.

CONCLUSION

NOM of rectal cancer that showed complete response to neoadjuvant therapy is a viable option in select patients. There are several controversies on the optimal method for and timing of assessment of complete response, surveillance strategies, and management of local recurrence. Hence, further studies are needed to help resolve these controversies to achieve the best outcomes of this novel management strategy.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Weng W, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH