Published online Dec 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i12.3875

Revised: September 26, 2024

Accepted: October 21, 2024

Published online: December 27, 2024

Processing time: 94 Days and 15.8 Hours

Liver transplantation (LTx) is vital in patients with end-stage liver disease, with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease being the most common indication. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an important indication. Portopulmonary hypertension, associated with portal hypertension, poses a significant perioperative risk, making pretransplant screening essential.

We report the case of a 41-year-old woman with PSC who developed severe pul

In conclusion, pulmonary arterial hypertension post-LTx is a rare but serious complication with a poor prognosis, necessitating further research to better understand its mechanisms and to develop effective strategies for prevention and treatment.

Core Tip: We present a young patient, four years post-liver transplant for primary sclerosing cholangitis, who developed World Health Organization group I pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Isolated PAH following liver transplantation is an exceptionally rare condition with an unclear pathology. While we believe it should not be considered idiopathic in the absence of portal hypertension or known etiology, we suspect the prior liver disease or current transplant may contribute to its development. Early recognition and timely intervention are essential for optimizing outcomes. This case highlights the need for vigilance in managing rare post-transplant complications and underscores the importance of further research.

- Citation: Alharbi S, Alturaif N, Mostafa Y, Alfhaid A, Albenmousa A, Alghamdi S. Pulmonary hypertension post-liver transplant: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(12): 3875-3880

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i12/3875.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i12.3875

Liver transplantation (LTx) is a vital lifeline for patients with end-stage liver diseases. It extends survival and significantly improves quality of life when other treatments fail. The leading indications for LTx have changed after the advent of potent and effective treatments for hepatitis C and B viral infections. In our region and worldwide, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has emerged as a leading indication for LTx[1]. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the bile ducts, leading to cirrhosis and liver failure, is another condition leading to liver LTx, and although rare, PSC accounts for 10%–15% of liver transplants in Europe and North America[2]. LTx is the definitive treatment, especially when complications such as portal hypertension or hepatobiliary malignancies arise[3].

Portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH), a form of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in patients with portal hypertension, is characterized by increased pulmonary pressure and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. PoPH affects 2%-6% of patients with portal hypertension, is observed in 5%-6% of liver transplant candidates[4]. Uncontrolled PoPH before LTx is linked to high perioperative morbidity and mortality, making severe PoPH a contraindication for LTx. Thus, screening for PoPH in liver transplant candidates is crucial for improving post-transplant survival rates[5,6]. Although rare, PH can develop months to years after LTx. Here, we report the case of a young patient with PSC who developed PAH several years after undergoing LTx.

Worsening dyspnea on exertion (DOE), classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Class III.

She presented with worsening DOE, classified as NYHA Functional Class III, and episodes of presyncope with mild exertion, prompting her admission for further evaluation.

History of PSC complicated by portal hypertension underwent a successful LTx from a living donor in November 2019. She was maintained on tacrolimus (1.5 mg BID). Her medical history was unremarkable for venous thromboembolism (VTE), connective tissue disease (CTD), or lung disease.

Her family Hx was unremarkable for similar condition, VTE or CTD.

Physical examination revealed signs of PH, such as a loud P2, on cardiac examination, but no signs of volume overload.

Laboratory tests revealed bicytopenia, with normal liver enzyme levels and function (Table 1). Notably, her NT-proBNP level increased to 6340 pg/mL.

| Variable | Result |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 3.03 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.5 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 81 |

| ANA | Negative |

| INR | 1.3 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 76 |

| HIV | Negative |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 2.4 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22 |

| AST (U/L) | 33 |

| Schistosoma antibody | Negative |

Radiological investigations included a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA), which revealed satisfactory opacification of the pulmonary arteries without filling defects, but signs of PH, including a dilated right ventricle, a straightened interventricular septum, and an enlarged pulmonary trunk measuring 3.8 cm, were evident. A ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan revealed no perfusion defects suggestive of clots. Abdominal ultrasonography confirmed a normal transplanted liver with homogeneous echogenicity and no focal lesions or biliary duct dilatation. The hepatic graft vasculature and portal veins were patent, with normal waveforms and velocities. The spleen was enlarged to 16.6 cm and reduced from 21.5 cm in a previous study. Owing to her DOE, echocardiography was performed, revealing severe PH, a severely dilated right ventricle, and a right ventricular systolic pressure above 60 mmHg. The left ventricle was normal. A small pericardial effusion was observed. Echocardiography before LTx in 2018 was normal, with no concern for PoPH.

Consequently, the cardiology team consulted for right heart catheterization, which revealed elevated right-sided filling pressures, severe precapillary PH, and low cardiac output and index according to the thermodilution method (detailed findings in Table 2). The patient also completed a 6-minute walk test and walked 486 m without significant desaturation. Three months after diagnosis, the patient underwent hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) assessment by an experienced interventional radiologist to evaluate occult portal hypertension. The results revealed a free hepatic venous pressure of 8 mmHg, wedged hepatic venous pressure of 11 mmHg, and HVPG of 3 mmHg.

| RA | mPAP | TCO | TCI | PVR | PAWP | PA sat (%) |

| 19 mmHg | 60 mmHg | 3.5 L/min | 1.5 L/min/m2 | 13 WU | 14 mmHg | 47 |

World Health Organization group I PAH after liver transplant.

Due to the severity of her disease, combination therapy with sildenafil 20 mg three times daily and macitentan 10 mg daily was initiated.

During her clinic visit after three months of her diagnosis, she reported significant improvement in her symptoms. Her current NYHA functional class was II, and she was able to walk 480 m. Additionally, her NT-proBNP level improved to 847 pg/mL and selexipag was added to further optimize her disease.

This case involves a 41-year-old female with PSC who developed de novo PAH several years after undergoing LTx. Her clinical presentation included DOE and presyncope, consistent with NYHA functional class III. Extensive diagnostic workup, including CTPA and V/Q scans, ruled out chronic thromboembolic PH. She also showed no evidence of PAH associated with CTD, congenital heart disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or schistosomiasis. Her liver function test results were normal, and ultrasonography of the transplanted liver showed no indications of recurrent portal hypertension.

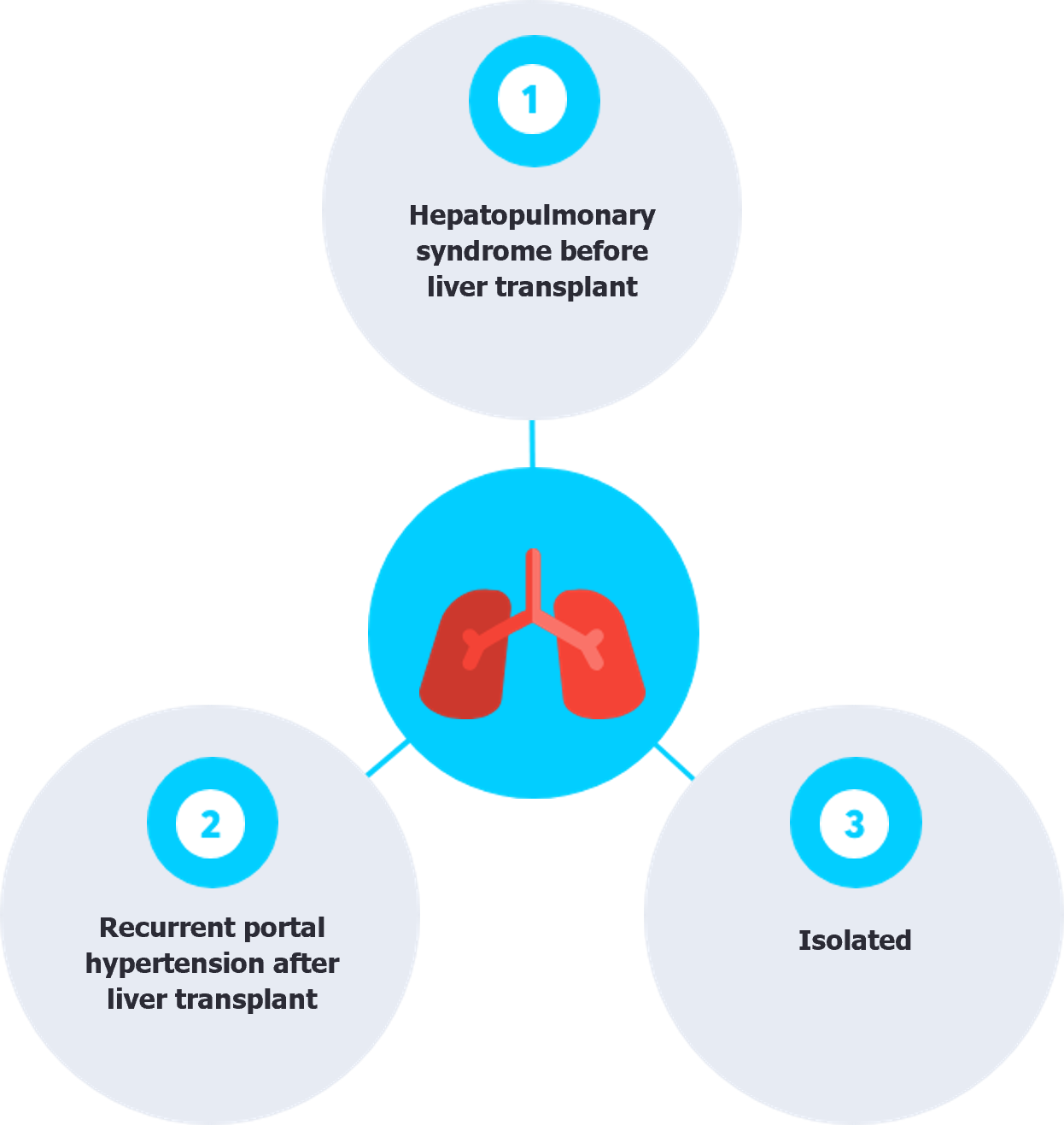

PH following LTx has been documented in three clinical scenarios: (1) Patients with pre-existing hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) before LTx, who also have coexisting PoPH, may develop PoPH early posttransplant because the unmasking effect of underlying vasoconstriction after vasodilation is corrected by LTx, as both conditions can coexist before transplantation[7]; (2) patients with clear evidence of recurrent portal hypertension, leading to PoPH as a complication; and (3) Isolated PH post-transplantation with no identifiable underlying pathology (Figure 1)[8].

The onset of PAH after LTx can vary significantly, from as early as one month to as late as 11 years post-transplantation, and it is associated with a high mortality rate. Generally, PAH post-transplant is associated with poor prognosis. However, a delayed onset of PAH following LTx may indicate a better prognosis, with survivors having a mean onset time of 5 years compared to 2 years in patients who do not survive[8].

Portal hypertension, whether recurrent or de novo after LTx, is a condition with the potential to lead to PoPH, driven by various medical and surgical factors. Medically, acquiring an infection such as hepatitis C virus following LTx can lead to liver fibrosis if not promptly detected and treated[9]. Another significant concern is the recurrence or emergence of liver steatosis, which affects up to 67% of patients transplanted for non-MASLD reasons and almost all MASLD patients within the first year[10]. Combined with the risk of liver rejection, these factors contribute to graft dysfunction and increase the risk of developing portal hypertension[11,12]. On the surgical front, complications such as hepatic venous outflow obstruction—caused by stenotic anastomoses or venous thrombosis—are critical concerns, as are portal vein stenosis and thrombosis, both of which can severely restrict blood flow and contribute to the onset of portal hypertension[13,14].

Our patient did not exhibit any evidence of HPS before the transplantation. Additionally, she showed no clear evidence of recurrent portal hypertension, with ultrasound of the transplanted liver indicating a normal transplanted liver and a reduction in the size of her previous splenomegaly. Additionally, HVPG measurement ruled out portal hypertension, with an HVPG of 3 mmHg[15,16]. To our knowledge, this is the fifth reported case of isolated PAH that developed after LTx[8,17]. Previous case reports from 1992 to 2006 included patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus, and biliary atresia. In 2007, a report described a young patient with PSC who developed recurrent cirrhosis and PoPH and ultimately died four months post-transplant[17].

PAH development following LTx, particularly in the absence of recurrent portal hypertension, remains a complex and poorly understood phenomenon. Describing it as idiopathic is difficult, especially in light of the patient’s history of liver disease and transplantation. This case contributes to the limited literature on this complication, suggesting that there may be an underlying predisposition to PAH in these patients, potentially driven by factors that have not yet been identified. We propose that LTx patients may be subject to a complex interaction of specific cytokines, triggering inflammation, vascular remodeling, and ultimately heightening the risk of PAH after transplantation[18]. Moreover, given this patient's history of autoimmune liver disease, we hypothesize that an underlying autoimmune mechanism could be at play, potentially driving the development of PAH—even in the absence of detectable autoimmune markers[19,20]. Genetic predisposition also appears to be a potential critical factor in this condition's pathogenesis. The fact that only a small percentage of cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension develop PoPH suggests a strong genetic component that persists even post-transplantation[21]. Therefore, it is essential to perform echocardiography in all post-LTx patients presenting with symptoms or signs suggestive of PH, as early detection may greatly improve outcomes compared to previous reports[22,23].

Following the 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines, we initiated upfront combination therapy with Sildenafil and Macitentan, taking advantage of her hospitalization to closely monitor blood pressure and liver function, with further modifications made based on her risk stratification during follow-up[24].

PAH is a rare but serious complication that can develop after LTx. It is associated with a poor prognosis and a high mortality rate. Understanding the pathophysiology of PH in LTx patients through further research is essential for developing effective prevention and management strategies.

| 1. | Alqahtani SA, Broering DC, Alghamdi SA, Bzeizi KI, Alhusseini N, Alabbad SI, Albenmousa A, Alfaris N, Abaalkhail F, Al-Hamoudi WK. Changing trends in liver transplantation indications in Saudi Arabia: from hepatitis C virus infection to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carbone M, Della Penna A, Mazzarelli C, De Martin E, Villard C, Bergquist A, Line PD, Neuberger JM, Al-Shakhshir S, Trivedi PJ, Baumann U, Cristoferi L, Hov J, Fischler B, Hadzic NH, Debray D, D'Antiga L, Selzner N, Belli LS, Nadalin S. Liver Transplantation for Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) With or Without Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)-A European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT) Consensus Statement. Transpl Int. 2023;36:11729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim YS, Hurley EH, Park Y, Ko S. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a condition exemplifying the crosstalk of the gut-liver axis. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1380-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | DuBrock HM. Portopulmonary Hypertension: Management and Liver Transplantation Evaluation. Chest. 2023;164:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wisenfeld Paine G, Toolan M, Nayagam JS, Joshi D, Hogan BJ, Mccabe C, Marino P, Patel S. Assessment and management of patients with portopulmonary hypertension undergoing liver transplantation. J Liver Transplant. 2023;12:100169. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Jasso-Baltazar EA, Peña-Arellano GA, Aguirre-Valadez J, Ruiz I, Papacristofilou-Riebeling B, Jimenez JV, García-Carrera CJ, Rivera-López FE, Rodriguez-Andoney J, Lima-Lopez FC, Hernández-Oropeza JL, Díaz JAT, Kauffman-Ortega E, Ruiz-Manriquez J, Hernández-Reyes P, Zamudio-Bautista J, Rodriguez-Osorio CA, Pulido T, Muñoz-Martínez S, García-Juárez I. Portopulmonary Hypertension: An Updated Review. Transplant Direct. 2023;9:e1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | DuBrock HM, Krowka MJ. The Myths and Realities of Portopulmonary Hypertension. Hepatology. 2020;72:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koch DG, Caplan M, Reuben A. Pulmonary hypertension after liver transplantation: case presentation and review of the literature. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | European Association for the Study of the Liver; Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel: Chair:; EASL Governing Board reprsesentative:; Panel members:. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series(☆). J Hepatol. 2020;73:1170-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 144.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vallin M, Guillaud O, Boillot O, Hervieu V, Scoazec JY, Dumortier J. Recurrent or de novo nonalcoholic fatty liver disease after liver transplantation: natural history based on liver biopsy analysis. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1064-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Unger LW, Mandorfer M, Reiberger T. Portal Hypertension after Liver Transplantation—Causes and Management. Curr Hepatology Rep. 2019;18:59-66. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Choi JY, Kim KW, Jang JK, Kwon HJ, Yoon YI, Song GW, Lee SG. Progression of Portal Hypertension in Acute Cellular Rejection After Liver Transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2022;20:742-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Unger LW, Berlakovich GA, Trauner M, Reiberger T. Management of portal hypertension before and after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:112-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee H, Lim CW, Yoo SH, Koo CH, Kwon WI, Suh KS, Ryu HG. The effect of Doppler ultrasound on early vascular interventions and clinical outcomes after liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2014;38:3202-3209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu Q, Leong S, Lee KA, Patel A, Chua JME, Venkatanarasimha N, Lo RH, Irani FG, Zhuang KD, Gogna A, Chang PEJ, Tan HK, Too CW. Hepatic venous-portal gradient (HVPG) measurement: pearls and pitfalls. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20210061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bochnakova T. Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021;17:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Acar S, Donmez G, Acar RD, Kavlak ME, Yazar S, Aslan S, Donmez R, Kargi A, Polat KY, Akyildiz M. Idiopathic Pulmonary Hypertension After Liver Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:1196-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Correale M, Tricarico L, Bevere EML, Chirivì F, Croella F, Severino P, Mercurio V, Magrì D, Dini F, Licordari R, Beltrami M, Dattilo G, Salzano A, Palazzuoli A. Circulating Biomarkers in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: An Update. Biomolecules. 2024;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shu T, Xing Y, Wang J. Autoimmunity in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Evidence for Local Immunoglobulin Production. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:680109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jones RJ, De Bie EMDD, Groves E, Zalewska KI, Swietlik EM, Treacy CM, Martin JM, Polwarth G, Li W, Guo J, Baxendale HE, Coleman S, Savinykh N, Coghlan JG, Corris PA, Howard LS, Johnson MK, Church C, Kiely DG, Lawrie A, Lordan JL, Mackenzie Ross RV, Pepke Zaba J, Wilkins MR, Wort SJ, Fiorillo E, Orrù V, Cucca F, Rhodes CJ, Gräf S, Morrell NW, McKinney EF, Wallace C, Toshner M; UK National Cohort Study of Idiopathic and Heritable PAH Consortium. Autoimmunity Is a Significant Feature of Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:81-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rochon ER, Krowka MJ, Bartolome S, Heresi GA, Bull T, Roberts K, Hemnes A, Forde KA, Krok KL, Patel M, Lin G, McNeil M, Al-Naamani N, Roman BL, Yu PB, Fallon MB, Gladwin MT, Kawut SM. BMP9/10 in Pulmonary Vascular Complications of Liver Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1575-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kubota K, Miyanaga S, Akao M, Mitsuyoshi K, Iwatani N, Higo K, Ohishi M. Association of delayed diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension with its prognosis. J Cardiol. 2024;83:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lau EM, Humbert M, Celermajer DS. Early detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, Badagliacca R, Berger RMF, Brida M, Carlsen J, Coats AJS, Escribano-Subias P, Ferrari P, Ferreira DS, Ghofrani HA, Giannakoulas G, Kiely DG, Mayer E, Meszaros G, Nagavci B, Olsson KM, Pepke-Zaba J, Quint JK, Rådegran G, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Tonia T, Toshner M, Vachiery JL, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Delcroix M, Rosenkranz S; ESC/ERS Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2023;61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 803] [Cited by in RCA: 1132] [Article Influence: 377.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/