Published online Nov 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i11.3598

Revised: September 19, 2024

Accepted: October 12, 2024

Published online: November 27, 2024

Processing time: 92 Days and 12.6 Hours

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is a rare malignant tumor and has non-specific clinical manifestations and imaging characteristics, making preoperative diagnosis challenging. Here, we report a case of PHL presenting primarily with fever, with computed tomography imaging showing a thick-walled hepatic lesion with low-density areas, resembling liver abscess.

The patient was a 34-year-old woman who presented with right upper abdominal pain and fever over 4 days before admission. Based on the patient’s medical history, laboratory examinations, and imaging examinations, liver abscess was suspected. Mesenchymal tumor was diagnosed by percutaneous liverbiopsy and partial hepatectomy was performed. Postoperative pathology revealed PHL. The patient is currently undergoing intravenous chemotherapy with the AD regimen and shows no signs of recurrence.

When there is a thick wall and rich blood supply in the hepatic lesion with a large proportion of uneven low-density areas, PHL should be considered.

Core Tip: Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is a rare malignant tumor and has non-specific clinical symptoms and imaging manifestations, and patients have a poor prognosis. Our patient was characterized by fever and a thick-walled cystic lesion, leading to our primary diagnosis of liver abscess. When a computed tomography scan shows the presence of a thick wall and rich blood supply in the hepatic lesion with a large proportion of uneven low-density areas, the possibility of PHL should be considered. Magnetic resonance imaging and biopsy can provide the assessment and diagnosis. If conditions allow, early radical surgery is the most effective treatment. In-depth studies are needed to find effective treatments for unresectable PHL.

- Citation: Wu FN, Zhang M, Zhang K, Lv XL, Guo JQ, Tu CY, Zhou QY. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma masquerading as liver abscess: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(11): 3598-3605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i11/3598.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i11.3598

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) is a rare malignant tumor that may originate from the hepatic blood vessels, bile ducts, or ligaments[1]. It is a subtype of primary hepatosarcoma, with unclear pathogenesis possibly linked to factors such as compromised immunity and so on. Preoperative diagnosis of PHL is difficult due to the lack of specific clinical symptoms and the diversity of imaging features. The definitive diagnosis relies on histopathology and immunohistochemistry[2]. Currently, there have been few reports on PHL, and its standardized treatment strategy has not yet been formulated. Patients with liver abscess typically have abdominal pain, fever, and intrahepatic cystic lesions. In rare instances, the combination of PHL and fever may lead to misdiagnosis of liver abscess. We report a case of PHL who presented with fever and a thick-walled cystic lesion, in the hope of providing a reference for future diagnosis and treatment of such cases.

The patient was a 34-year-old woman who presented with right upper abdominal pain and fever over 4 days before admission.

Four days ago, the patient experienced right upper abdominal pain and a fever, her specific temperature is unknown. She took amoxicillin, but the fever persisted and her symptoms were not relieved.

The patient underwent surgery for a right clavicle fracture due to trauma two years ago and recovered well.

The patient denied any history of smoking, drinking, or exposure to toxic substances. He also denied any family history of genetic disease.

The patient’s temperature was 37.3 °C, heart rate was 128 bpm, and blood pressure was 124/76 mmHg. Her abdomen was soft, with mild tenderness on the right upper quadrant, and no rebound tenderness or muscle rigidity. The height of the patient was 158 cm and weight of the patient was 55 kg.

Laboratory examinations showed that the patient’s procalcitonin was 0.20 ng/mL (reference range: < 0.05 ng/mL), C-reactive protein was 142.25 mg/L (reference range: < 8.0 mg/L), white blood cell count was 12.6 × 109/L [reference range: (3.5-9.5) × 109/L], carbohydrate antigen 19-9 was 95.5 U/mL (reference range: < 43.0 U/mL), and hepatitis B surface antibody was negative. Alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and liver function were normal.

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan conducted in the emergency department showed a mixed low-density lesion (6.5 cm × 9.7 cm × 9.6 cm) in the right lobe of the liver, with visible septations and fluid levels. The edges and septations of the lesion were significantly enhanced on the enhanced scan, and our primary consideration was liver abscess (Figure 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a massive abnormal signal lesion (6.5 cm × 9.7 cm × 7.0 cm) in the right lobe of the liver, with septations and fluid levels. The lesion showed heterogeneous hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2WI. Enhanced MRI revealed that the edges and septations of the lesion were significantly enhanced during the arterial phase, and the enhancement partially fused and filled toward the center of the lesion during the portal phase and delayed phase. Diffusion-weighted imaging showed a hyperintense signal and the corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map showed a decreased signal intensity in parts of the wall of the lesion (Figure 2A-H).

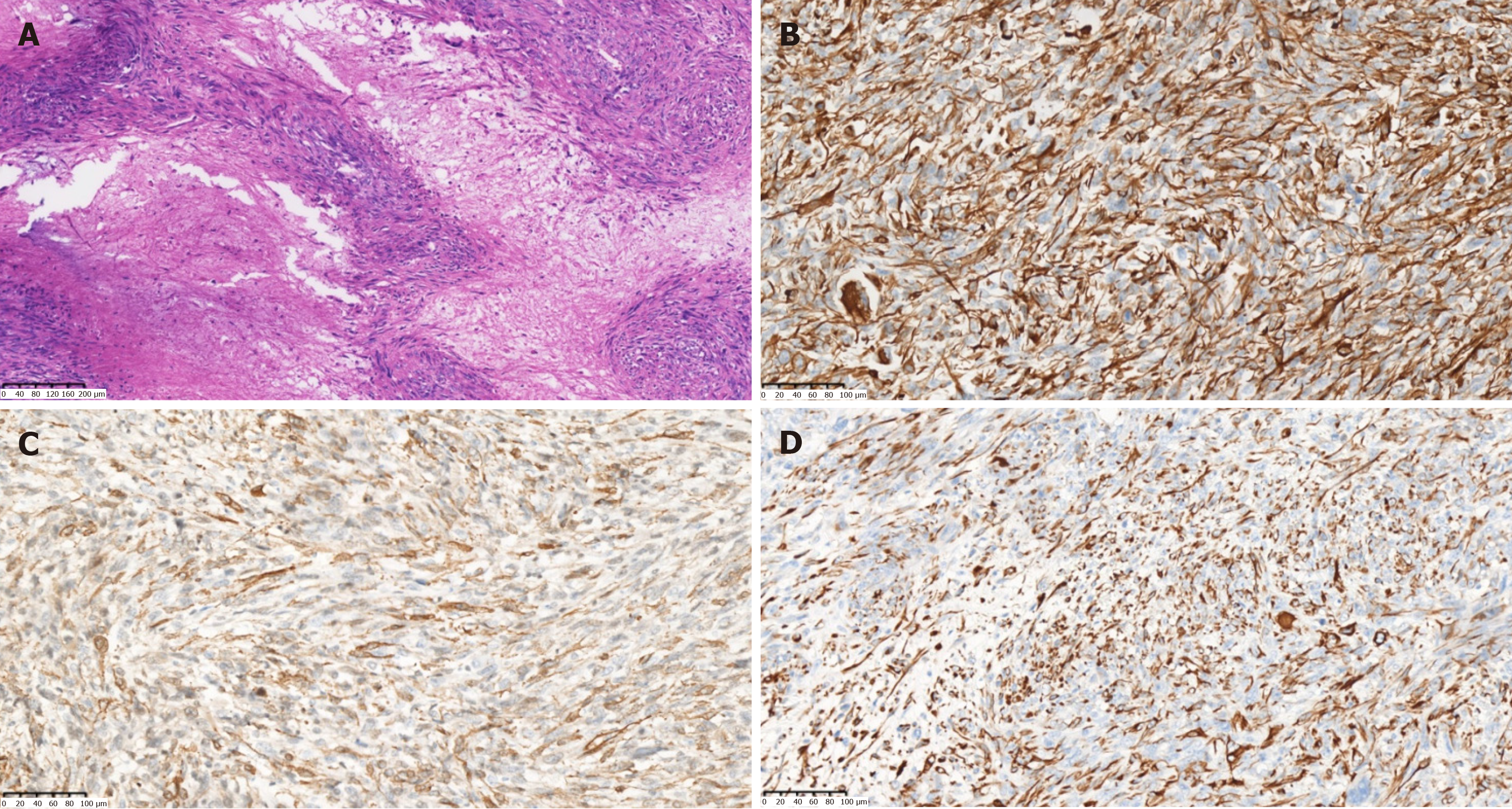

Combined with the findings of MRI, the patient was considered to have an intrahepatic malignant tumor with intratumoral bleeding. Further ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed to confirm the nature of the lesion. Microscopic examination revealed that the tumor was composed of spindle-shaped cells, arranged in a woven pattern, and irregular cell nuclei and frequent mitotic images were observed (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemistry showed positive results for vimentin, smooth muscle cell markers [smooth muscle actin (SMA)], desmin, and Ki-67 (approximately 30%). All others were negative: S-100, SATB2, CD117, ER, CD10, PR, CK7, DOG-1, STAT6, Melan-A, and HMB45 (Figure 3B-D). Considering the immunohistochemistry findings, a mesenchymal-origin tumor was initially suspected. In order to exclude other primary lesions or metastases, a whole-body positron emission tomography-CT scan was con

Combined with preoperative evidence, a primary hepatic mesenchymal malignancy was considered.

The patient’s hepatic lesion was diagnosed as a malignant tumor and obvious distant metastasis and surgical contraindications were excluded. Therefore, partial hepatectomy was performed.

During the operation, an irregular solid-cystic tumor (10 cm × 9 cm) was found in the right posterior lobe of the liver. The tumor appeared to have a capsule, with a white-yellow appearance on the cut surface. The cystic part of the tumor was characterized by reddish fluid and old blood clots (Figure 4). Microscopic examination revealed that the tumor exhibited large areas of map-like necrosis, spindle-shaped tumor cells arranged in bundles, cellular atypia was noticeable, and mitotic images were extremely common (Figure 5A). The liver capsule was involved, no definite tumor thrombus was seen in the vessels, and the liver resection margin was negative. Immunohistochemistry revealed vimentin+, SMA+, desmin+, h-cald-, CD117-, CD34-, BcL-2-, STAT6-, DOG-1-, S-100-, MyoD1-, Melan-A-, HMB45-, Myogenin-, Ki-67+ (approximately 75%) (Figure 5B-D). The final diagnosis was PHL. The patient recovered well after surgery, and she is currently receiving AD (doxorubicin liposome 53 mg intravenous infusion via micro-pump 16 hours, dacarbazine 675 mg intravenous drip d1-2) chemotherapy, with a 21-day cycle. No recurrence or metastasis has been observed.

Primary hepatosarcoma is a rare malignant tumor, accounting for approximately 2% to 3% of hepatic malignant tumors. The most common primary hepatic sarcoma is angiosarcoma, with leiomyosarcoma accounting for only about 12%[3]. It has been reported that PHL may originate from the intrahepatic blood vessels, bile ducts, or ligaments[1]. The path

Patients with PHL often have no obvious symptoms in the early stages and may develop abdominal pain, jaundice, anorexia, nausea and vomiting after tumor enlargement. Fever may be the primary manifestation in very few patients due to liquefaction and necrosis in the tumor[6]. PHL originating from the hepatic vein may lead to Budd-Chiari syn

Ultrasonography usually shows a hypoechoic or heterogeneous echogenic lesion[1]. CT findings generally describe a large, well-defined, heterogeneous low-density lesion with internal and peripheral enhancement, or a cystic lesion with enhanced thick walls. During the portal phase and delayed phase, enhancement may either wash out or partially fuse and fill toward the center of the lesion. In some cases, enhancement begins during the delayed phase[9,10]. Combined with pathology, it was found that the low-density areas on CT scans do not solely represent liquefied necrosis, and a large proportion was still tumor parenchyma, which could be scattered with old hemorrhage[11]. In addition, MRI characteristically displays homogeneous or heterogeneous hypointensity on T1WI and hyperintensity on T2WI, and the enhan

The varied and non-specific imaging characteristics of PHL necessitate reliance on histopathology and immunohistochemistry for accurate diagnosis. Histopathology usually shows intersecting bundles of spindle-shaped cells with hy

At present, there is no consensus on the standardized treatment strategies for PHL, but almost all reports suggest that surgical resection is currently the most effective treatment[14]. Negative tumor margins and a tumor diameter less than 10 cm are major favorable prognostic factors[15], so early detection and curative resection are important for PHL patients. Hilar lymph node metastasis is rare, and there is a lack of relevant research on whether regional lymph node dissection should be performed routinely during the operation[15]. For early-stage patients without metastasis, radiofrequency ablation appears to be an acceptable candidate for consideration[16]. The application of liver transplantation for PHL remains controversial[17]. Adjuvant therapy following curative surgery is still in the exploratory phase[18,19]. Due to the aggressive metastatic potential of PHL, adjuvant therapies such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy are recommended following surgical resection[2]. For advanced-stage patients ineligible for surgical intervention, systemic chemotherapy is commonly employed. Chemotherapy regimens are mostly for soft tissue sarcomas, and anthracycline-based chemo

The prognosis of PHL is poor, with a median overall survival of 19 months, and the 1-, 2- and 5-year survival rates are approximately 61%, 41%, and 14%, respectively[15]. Early curative surgery can improve prognosis significantly, and disease-specific survival rate at 5 years after R0 resection can reach 67%[2]. Advanced PHL is prone to metastasis, with the lungs being the most common site of metastasis, followed by the pleura/thorax/diaphragm, kidneys and bones[15].

We report a rare case of PHL masquerading as liver abscess, which is very confusing. When there is a thick wall and rich blood supply in the hepatic lesion with a large proportion of uneven low-density areas, PHL should be considered. MRI should be performed to assist evaluation, and percutaneous liver biopsy is feasible to confirm the diagnosis. Early radical surgery can improve the prognosis.

| 1. | Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, Kubota K. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ahmed H, Bari H, Nisar Sheikh U, Basheer MI. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:1830-1839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Dematteo RP. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Iida T, Maeda T, Amari Y, Yurugi T, Tsukamoto Y, Nakajima F. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. CEN Case Rep. 2017;6:74-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martins ACA, Costa Neto DCD, Silva JDDE, Moraes YM, LeÃo CS, Martins C. Adult primary liver sarcoma: systematic review. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2020;47:e20202647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Esposito F, Lim C, Baranes L, Salloum C, Feray C, Calderaro J, Azoulay D. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver: Two new cases and a systematic review. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2020;24:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giakoustidis D, Giakoustidis A, Goulopoulos T, Arabatzi N, Kainantidis A, Zaraboukas T. Primary gigantic leiomyosarcoma of the liver treated with portal vein embolization and liver resection. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2017;21:228-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vella S, Cortis K, Pisani D, Pocock J, Aldrighetti L. Case of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma successfully treated with laparoscopic right hepatectomy. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lv WF, Han JK, Cheng DL, Tang WJ, Lu D. Imaging features of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: A case report and review of literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2256-2260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Teng CD, Hu MZ, Ye Q, Weng XH, Xu CY. [CT imaging features of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma]. Xiaohua Waike. 2021;20:913-919. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Xu AM, Cheng HY, Jia YC, Wu MC. [CT findings of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (Analysis of 6 cases)]. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 2004;10:205-207. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Soyer P, Blanc F, Vissuzaine C, Marmuse JP, Menu Y. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver MR findings. Clin Imaging. 1996;20:273-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mitra S, Rathi S, Debi U, Dhiman RK, Das A. Primary Hepatic Leiomyosarcoma: Histopathologist's Perspective of a Rare Case. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:321-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Garrido I, Andrade P, Pacheco J, Rios E, Macedo G. Not all liver tumors are alike - an accidentally discovered primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: A case report. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:860-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chi M, Dudek AZ, Wind KP. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in adults: analysis of prognostic factors. Onkologie. 2012;35:210-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Awad A, Pal K, Yevich S, Kuban JD, Tam A, Odisio BC, Gupta S, Habibollahi P, Bishop AJ, Conley AP, Somaiah N, Araujo DM, Zarzour MA, Ratan R, Roland CL, Keung EZ, Huang SY, Sheth RA. Safety and efficacy of percutaneous image-guided ablation for soft tissue sarcoma metastases to the liver. Cancer. 2024;130:2703-2712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liang X, Xiao-Min S, Jiang-Ping X, Jie-Yu Y, Xiao-Jun Z, Zhi-Ren F, Guo-Shan D, Rui-Dong L. Liver transplantation for primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report and review of the literatures. Med Oncol. 2010;27:1269-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsai PS, Yeh TC, Shih SL. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a 5-month-old female infant. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2013;2:2047981613498722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu W, Liang W. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma presenting as a thick-walled cystic mass resembling a liver abscess: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | von Mehren M, Kane JM, Agulnik M, Bui MM, Carr-Ascher J, Choy E, Connelly M, Dry S, Ganjoo KN, Gonzalez RJ, Holder A, Homsi J, Keedy V, Kelly CM, Kim E, Liebner D, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Mesko NW, Meyer C, Pappo AS, Parkes AM, Petersen IA, Pollack SM, Poppe M, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Shabason J, Sicklick JK, Spraker MB, Zimel M, Hang LE, Sundar H, Bergman MA. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:815-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Takehara K, Aoki H, Takehara Y, Yamasaki R, Tanakaya K, Takeuchi H. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma with liver metastasis of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5479-5484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shamseddine A, Faraj W, Mukherji D, El Majzoub N, Khalife M, Soubra A, Shamseddine A. Unusually young age distribution of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: case series and review of the adult literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhu KL, Cai XJ. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma successfully treated by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Feretis T, Kostakis ID, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Mantas D, Nonni A, Kouraklis G, Dimitroulis D. Primary Hepatic Leiomyosarcoma: a Case Report and Review of the Literature. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2018;61:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/